*****

Introduction • Guilhem De Peiteus • Marcabru • Beatritz de Dia • Bernart de Ventadorn • Raimon d’Avinhon • Bertran de Born • Guiraut Riquier

Translator: Peter Sirr

*****

Introduction

This journey began, as often happens, by a combination of fluke and compulsion. While looking for something else, I happened on lines from Guilhem de Peiteus in contrasting versions by Paul Blackburn and W.D. Snodgrass. The translations were interesting for the different approaches they took to the original: one relatively smooth and straightforward, the other more broken, jumpy and contemporary. But it was the lines in what we now call Old Occitan that I couldn’t get out of my head. The opening gambit, Farai un vers de dreyt nien (‘I’ll make a verse out of nothing at all’) leapt from the page, seeming to arrive fully formed in its self-confident flourish and strut, a meta-poem playing comfortably with the idea of poetry and the role of the poet, alive with a sense of possibility and a line of debunking mockery. Guilhem de Peiteus, feudal overlord, Crusader, grandfather of Eleanor of Aquitaine, rode his horse-poem out of the medieval mist and started a tradition which privileged poets and the art of making poetry, with new forms and modes of address, in a way that hadn’t happened before.

There’s something contradictory about Guilhem’s poems – he’s credited with being the first troubadour, yet the swagger and sophistication suggests more the pinnacle of an already achieved tradition than a raw beginning. And the whole troubadour moment is a bit like that. It appears unexpectedly, reaches its high point around the last half of the twelfth century and the first half of the thirteenth century, and is effectively over by the fourteenth century. This brief blaze, leaving behind thousands of works by several hundred poet-performers, continued to light up European literature for centuries. The German Minnesänger, the trouvères of northern France, the poets of the dolce stil nuovo in Italy, the Galaico-Portuguese, Catalan and Spanish poets of the Iberian peninsula and poets in these islands from Chaucer to Gearóid Iarla, are all influenced by the Occitanian pioneers. Dante, like many Italian pets of his era, considered writing in Occitan before plumping for Italian. In the Purgatorio he meets the original ‘miglior fabbro’, Arnaut Daniel, who addresses him in Old Occitan: ‘Ieu sui Arnaut, que plor e vau cantan’ (‘I am Arnaut, who weeps and goes singing’).

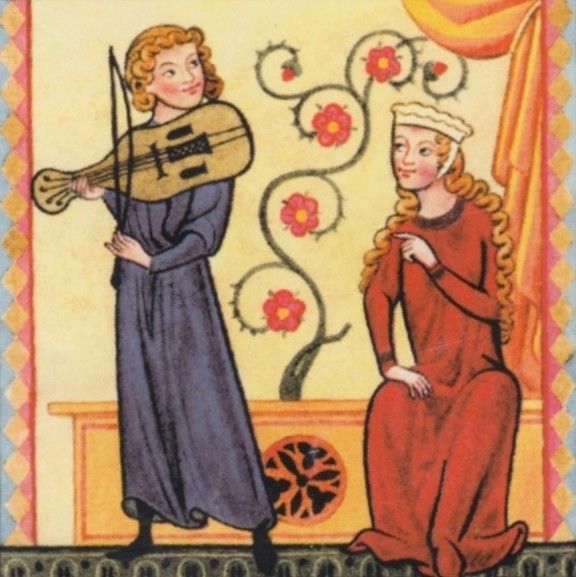

The troubadours don’t exactly come out of nowhere – there had been medieval Latin poetry, after all, and the Hispano-Arabic and Jewish poetry of Al-Andalus – but European lyric poetry as we know it effectively begins with them. To read the likes of Guilhem, Cercamon, Maracabrun, Arnaut Daniel, the incomparable Bernart de Ventadorn or the very different Bertran de Born, or the trobairitz like Beatriz de Dia, Tibors or Clara d’Anduza, is to be struck by the wit, passion, invention, energy as well as the music of the poetry. And music plays a big part; this was a performative tradition – the poems sung by joglars, who sometimes themselves became trobadors – and many of the actual melodies of these poems survive and are performed by early music groups today.

The poetry has, of course, been much translated, yet the achievement of the troubadours is still, for most of us, elusive. The abstract seeming courtly love sometimes resolves itself into a slightly cartoonish image of lovelorn poets and idealised love, a sort of medieval Hallmark of romantic gestures. We’re aware of the fact of the troubadours but the actual poems rarely impinge. What was extraordinarily; fresh and innovative for Arnaut Daniel or Bernart de Ventadorn can seem unapproachable or hackneyed to us in translation. In English this is complicated by the intersection of the troubadours with the heights of Modernism through the translations of Ezra Pound. If Pound ‘invented’ Chinese poetry in English he also pulled the work of the troubadours back into the light of attention, albeit he did so – in contrast to his Chinese adaptations – in often oddly archaising versions that looked back to the Elizabethans and sixteenth century Scots more than to contemporary idiom. Pound created a brilliantly estranging veil of his own that needs to be gently pushed aside by succeeding generations to get at the original work again. That, of course, is one of the beauties of translation; the original stays put while translators sit in the booth of their moment and broadcast their short range FM signals. Translation is never fixed or finished; it answers a contemporary need to engage with and remake in the language we have available to us whatever calls out to us from the past.

One of the things that drew me into this work was the confluence of music and poetry. As I read and attempted to translate, I also listened. Often the first thing I did was to listen to the poems sung by performers like Paul Hillier, Gérard Zucchetto, Ensemble Micrologus, Els Trobadors, Joel Cohen, Ensemble Celadon and many others. This was usually followed by staring at and trying to recite the text. The journey into this work was also an excursion into the language. Now called Old Occitan to distinguish it from the contemporary language, it was the vernacular of the greater part of Southern France, a distinct Romance language whose name comes from oc, the word for yes. The trobadors themselves would have called it proensal (‘the language of Provence’) or lemozin (‘the language of Limoges’) or simply romans (‘vernacular language’). I sank myself in William Paden’s An Introduction to Old Occitan and numerous dictionaries, and tried to decipher the original texts. I wanted, as much as possible, to work from the originals; to have that primal relationship with their forms and music. My aim was to find a matching music in English, to make poems as close as I could manage to the spirit of the originals.

These are not, it should be said, scholarly translations – they commit many cardinal translation sins and would be expelled from any respectable troubadour convention. I played fast and loose with form and image; I left out large chunks of poems in order to get at the essence; I joined up the bits I liked from several poems (‘Bernart’s Verses’); I started off with the original but soon lost the run of myself (‘A Busy Man’); in one case (‘The Last Song’) I added an imaginary final stanza. I included poems of my own inspired by the tradition, as if a trobador had gone to sleep and woken in the mountains of Cork or Kerry. I had fun.

Despite their brilliance and long lasting influence we know almost nothing about the men and women who were the trobadors and trobairitz. The vidas, or brief prose biographies, written much later, are essentially fictions. Many of them were written by Uc de Saint Circ, himself a poet and therefore, necessarily, not the most reliable witness. Maybe Jaufre Rudel really did die in the arms of the object of his far-off love, the Countess of Tripoli; maybe the jealous Raimon of Roussillon really did remove the heart of Guilhem de Cabestanh, roast it in pepper sauce and serve it to his wife; maybe Bernart de Ventadorn was a baker’s son; maybe Peire Vidal was indeed ‘one of the craziest men who ever lived’ – it probably wouldn’t be wise to put money on any of it, but even these fictions give a sense of the excitement and fevered interest that attended the poets and their poems. What we have in the end, though, are the poems themselves which still speak with the force and urgency they had when they were first written and performed. If I’ve got a fraction of that into these versions, I’ll be happy.

*****

Guilhem De Peiteus: Nothing Song

Farai un vers de dreyt nien

Nothing: great subject, fit for a poem.

Here’s one: not me, not anyone, not

love, youth, any

of that. Nothing at all.

I wrote it in my sleep riding home, my

horse-poem.

I don’t know when I was born.

I’m not cheerful, and not angry.

No stranger here, no native either.

If you ask me

I was carried off and roughly magicked

on a dark night.

Hard to know if I’m asleep or awake, please

knock on my door and tell me.

I know I’m in heart trouble,

afflicted, sore. There again, put

the pills back in the box: why

should I care?

Timor mortis does its trick.

They say (they always say)

the cure is on the way.

Call the doctor, call the nurse

give them the prize if I improve,

otherwise not.

I have a friend, I’ve never seen her,

a vision beheld, the purest dream.

She never pleased me, nor ever

let me down. No matter,

no Normans or Frenchmen

darken my door.

I never saw her, still I love her.

Do I contradict myself?

Don’t worry,

judge and jury have left the room.

The thing is

I love another: nicer, prettier. I love her more.

I don’t know where she is,

in the mountains, on the plains.

Nor can I say

she’s done me wrong. Quiet, so;

and since it pains me to stay here

I’ll be on my way.

Well, that was it. I don’t know

who I was singing for.

I’ll send it to someone who’ll send it on

to someone somewhere in Anjou

who one day, out of the blue,

will send me the key.

*****

Guilhem de Peiteus: 1071 – 10 February 1126, 9th Duke of Aquitaine and Count of Poitou. He was also one of the leaders of the Crusade of 1101, but he is best known as the earliest troubadour whose work survived. Eleven of his songs are extant. His granddaughter was Eleanor of Aquitaine, a great patron of troubadours. Richard Coeur-de-Lion, her son, wrote poetry in Occitan.

*****

Marcabru: The worst of times

Lo vers comens quan vei de fau

When leaves fall my song begins

when birds stop singing

and frogs no longer croak

is when I come in, all

flint, tinder and steel

to scorch the little buzzing

hornet poets who mock my song

with the exhausting zest

of the talentless.

For these are the worst of times:

here’s virtue unhorsed

and fallen into filth

here’s gold persuading gold.

Yet for all

venal Rome cavorts

and evil preens on every road

mark this poet’s word:

the true profit will be regret.

Cowardice is all the rage

and honesty cast down.

Hardly a son

is worth the ground

his father walks on

and no one now can argue

there’s courage to be found

beyond Poitou.

To be young, these days,

is to wither in bickering

and I know

if I hunt high and low

I still won’t find

a courtly man

whose heart is true

whose mind’s not lame.

So generous,

whatever they give

comes with a sour puss

and added tax.

For praise or blame

they couldn’t care less.

The world is skewed:

a lord in every peasant’s bed

boors in silks

on the battlements

and every prancing foal

soon turned to mule.

You think

I make this up?

Dissect these verses

with your sharpest knife

you won’t find even by fraud

one unjust word.

I say this

the poet Marcabru

the wealthless man, his mind

his demesne, his empty hand.

*****

Marcabru, also spelled Marcabrun(born c. 1130–48), Gascon poet-musician and the earliest exponent of the trobar clus, an allusive and deliberately obscure poetic style in Old Occitan. Marcabru’s innovative technique and humour are evident in all his verse, and he was widely imitated and admired. More than 40 of his poems have survived. His favourite subject, however, was the contrast of fin’ amors (pure, perfect love) and amars (the sensual courtly love praised by his contemporaries). A vehement moralist, Marcabru criticized the nobility and other troubadours for distorting the true courtly virtues. Many of his finest poems are in direct response to works by other poets.

*****

Beatritz de Dia: ‘How I’d like him …’

Estat ai en greu cossirier

How I’d like him

oh

how I would like him my

cavalier

even if for a single night

naked in my arms

his head resting on my lap

I love him, more

than Floris loved Blanchflor

I did not tell him this

Everyone, everyone should know

To him I gave my heart my soul

my reason my eyes my life

My tender beautiful cavalier

when will I have you for myself?

For one night only

naked in your arms

If you could only take

my husband’s place

and swear to me you’ll answer

when I call, and heed my desire.

*****

Beatritz de Dia: The Comtessa de Dia (Countess of Die), who lived in the late 12th century, was a trobairitz (female troubadour). She is only known as the comtessa de Dia in contemporary documents, but was almost certainly named Beatriz or Beatritz and likely the daughter of Count Isoard II of Diá in southern France. Her poems were often set to the music of a flute. Five of her works survive. Her song A chantar m’er de so qu’eu no volria is the only canso by a trobairitz to survive with its music intact.

*****

Bernart de Ventadorn: The Lark

Can vei la lauzeta mover

When I see the lark

beat its wings against the sun

self-forgetting, falling

for the sweetness of it

then such envy comes on me

of all who go rejoicing.

How is my heart

not crushed by desire?

So much I thought I knew

of love, who know nothing of it,

who can’t help loving her

from whom I’ll have nothing.

All of my heart she has, all of me.

Her own self she has, all the world.

When she left, nothing stayed

but longing, nothing but love of her.

No power I’ve had, or control

from the instant

she let me look into her eyes,

the mirror that so pleased me.

Since I saw myself there

I’ve acted the fool,

as lost in its regard

as Narcissus at his pool.

I’ve done with that, I’ll trust

no love again.

As once I defended them

now I’ll leave women alone.

I am the fool on the bridge

befuddled by stone, landing in water,

I am the lark

that soared too high.

Since she gets no pleasure from my prayers

she can have no mercy:

there’s nothing left but exile.

When I see the lark

I’ll go away, somewhere under the sun:

I shall renounce song, I shall

rail against it, and hide

from love, and hide from joy.

*****

Bernart de Ventadorn, the greatest of all the Occitan troubadours, was born before 1152, in Limousin, Aquitaine and died around 1195 in Dalon). Bernart is known to have travelled in England in 1152–55. He lived at the court of Eleanor of Aquitaine and then at Toulouse, in later life retiring to the abbey of Dalon. He is remembered for his mastery as well as popularisation of the trobar leu or light style of courtly love poetry. His poems, 45 of which survive, express emotional power combined with lyric delicacy and simplicity. He also composed his own music and is unique among twelfth century secular composers for the amount of his music that has survived –eighteen of his poems have their melodies intact. In the final fragment (Canto CXX) of The Cantos, Ezra Pound, who had a lifelong fascination with the troubadours, quotes from Bernart’s Can vei la lauzeta twice.

*****

Raimon d’Avinhon: A Busy Man

Sirvens sui avutz et arlòts

A man gets busy

and the world is wide

a servant I was and more

besides a gilder a girdler

a ceiler a carver a dapifer

an archer an arbalestier

a pimp a peddler a purser

fishmonger swordswallower

I can make walls sew sleeves

falconer hawkspotter I shot

a hundred birds and cooked them

a songmaker a poet

sharpwitted tender

five months a jaundiced joglar

cackling for my supper

a butcher a strap-maker

a whore a thief

I herded cows sheared sheep

shovelled shit a gambler

a priest a knight in armour

a knacker a knifer

a hacker a hatter

a wetnurse a drynurse

a vaginarius

a chickengriller a bellmaker

a merchant a waferer

an innkeeper a tumbler

a molecatcher a ratkiller a glover

a broomdasher a lover

I made corsets dug graves

built boats rode the waves

I was a lancier a lanternmaker

a marleyman a milliner

a scythesmith a seamster

spurrer thonger threadmaker

a bather a launderer

a chamberlain a chimneysweep

I made hurdles I put up tents

took down tents put up

pavilions emptied privies

a scullion a sperviter

a spectaclesmaker

a trencherman a nailer

a siever a sawyer

a currier a gurrier

a fuller a fletcher

a pissprophet a dungcalculator

a ferryman a librarian

a cardinal a curate a critic

a barker a fiddler a chancer

a limner a lutenist a pugilist

an annalist an archivist an alchemist

an aerialist a balladist

a cabalist a chemist

an aromatherapist

a linenpinner a yarnspinner

a maker of lists

oh I was a quare one

with nowhere to hide

a man gets busy

and the world is wide.

*****

Raimon d’Avinhon, who may have been a physician, was a troubadour from Avignon. He wrote one surviving sirventes, Sirvens sui avutz et arlotz, is preserved in a manuscript of 1254.

*****

Bertran de Born: Lament for the Young English King

Si tuit li dol e·lh plor e·lh marrimen

Put them all together, pile them up, every

human misery, sharp grief, keened pain;

every cry ripping the world asunder,

thunderbolts and trickery, the slipped knife

tearing, the weeping and the wailing are nothing

against the death of the young English king.

His fame is behind him, his youth broken:

now let the world with sorrow darken.

They mourn him who are left without him,

his courtly army, his clever joglar, his trobador.

Death the resourceful, death the unflinching

has carried from earth the young English king.

From here to the moon the field can stretch

before we sew our crop of loss.

Death the brave, the richly nourished,

stand on your table, raise your glass

for you have taken the best of us;

whatever of worth, whatever of grace

we vested in him, the young English king.

How many might die that he should live –

if only God were by reason swayed

how we’d quarrel with blood unspilled.

From this poor world love flies away,

what seems like joy is the cruellest deceit;

nothing blossoms that doesn’t fade,

what glistens today tomorrow will tarnish.

The sun rises and fiercely announces

what’s most loved will soonest vanish.

We loved him most who now is gone,

the young English king who taught us well.

You who for our distress

made this grim world Your dwelling place

and for our salvation accepted death

we ask for mercy, we ask Your pardon

for the young English king, that he may

with good companions walk

in sun-pierced meadows, and lie untroubled

where grief never entered, nor sorrow took hold.

*****

Bertran De Born, a minor nobleman sharing with his brother the castle of Hautefort (Occitan: Autafòrt) in the Périgord, was born in the early 1140s. He was married twice, with five children, and by 1192 had become a monk and died sometine between this and 1215. Twice he went to war with his brother Constantin for sole possession of the family heritage. Richard the Lion-Heart, Duke of Aquitaine, initially favoured Constantin, successfully besieging Bertran’s fortress and expelling him (1183). Later, however, lord and vassal were reconciled; and Bertran, restored to his lands, helped Richard and his brothers in their rebellions against their father, Henry II of England. After Richard became king of England (1189), Bertran accompanied him on the crusade to Palestine. After returning to France, he wrote violently militant poetry, egging on Richard in his wars with Philip II of France. Many of the sirventes which form the main body of his work are reactions to political events, and all of his work is characterised by its intensity, realistic vividness and considerable style, qualities recognised by Dante, who placed him in the Inferno, in which he carries his severed head before him like a lantern.

*****

Guiraut Riquier: The Last Song

Be’m degra de chanter tener

Enough. The ink is dry,

the tongue parched, the

whole tradition pauses,

falters. Stop, then.

Art shrinks

from a doleful heart

and I have

no lightness left, nor song

to speak of.

Useless to complain:

the hurts of the past,

miseries of the present,

whatever the future holds.

And still it comes out,

the punctual tune,

the gift still spinning

whether I sink in gloom

or salute the moon.

Fulfilment, despair

I weigh them both,

calibrate

the brimming beaker,

the empty chair.

The truth is

I can do nothing else.

His vocation, they’ll write,

was to be born too late.

What shall we do

for song when the singer’s

gone? No one wants

it now, and who, in all honesty,

would not prefer

the whisper in the corridor,

the princess by the pool?

All that fiddle, all that

pain. What we most cherished

no one in his right mind

would want or need.

The boutiques are full,

the trinkets glitter,

all the world is sale agreed.

Remember, though,

the triumph of vice

is that we could well die twice

lashed by the Saracen

and God’s own blade.

Yet even this late

still I ask, Sweet

Lady who forgives all,

for us now intercede.

Shine your light, Lord,

that our eyes can feast

on what you made

and the heart from malice

at last be swayed

and let some

meagre illumination

fall our way

to remember us by,

a torch flaring

down centuries

to where it all began,

the lark

as yet unrisen, dawn

trembling on the hawthorn.

*****

Guiraut Riquier was born around 1230 in Narbonne, where he died in 1292. He is among the last of the Occitan troubadours – often termed The Last Troubadour – and is also known as a careful anthologist of his own works, preserving more than a hundred of his songs and melodies for 48 of them. His first extant poem dates from 1254, and he practices his art at the court of the viscount of Narbonne for the following sixteen years before moving to Spain when his patron died. He served at the court of Alfonso X of Castile and Léon, who was one of the great patrons of the age.

*****

Peter Sirr lives in Dublin where he works as a freelance writer and translator. He teaches a course in literary translation for the Translation Centre in Trinity College, Dublin. His most recent collection of poems is The Rooms, published by Gallery in 2014 and shortlisted for the Irish Times Poetry Now Award. The Thing Is, published by Gallery Press in 2009, was awarded the Michael Hartnett Prize in 2011. The Gallery Press has also published Marginal Zones (1984), Talk, Talk (1987), Ways of Falling (1991), The Ledger of Fruitful Exchange (1995), Bring Everything (2000), Selected Poems and Nonetheless (both 2004). A novel for children, Black Wreath, was published by O’Brien Press in 2014. Sway, Versions of Poems from the Troubadour Tradition, will be published in October 2016. He is a member of Aosdána, the Irish Academy of Artists.

Websites: petersirr.com,

http://petersirr.blogspot.co.uk/

6 thoughts on “Peter Sirr: Under the Sway of the Troubadours”