*****

Mari Ellis Dunning Crocodile ISBN 9781838230395; Nicholas Murray The Culture Man ISBN 9781919173511; Andrew Neilson Summars Are Other ISBN 9781919173504. All Rack Press £6.00. Reviewed by Ian Pople

Fabrics, Fancies & Fens by Gerald Killingworth. £9.99. Tears in the Fence. ISBN 978-1-9000201-4-5. Reviwed by Sue Kindon

*****

Mari Ellis Dunning’s Crocodile is described on the back cover as exploring ‘domestic violence and coercive control through the eyes of victim, reptilian perpetrator and the justice system.’ Its ten pages of poems explore those motifs with an almost dizzying range of forms. The short opening sequence ‘Girl’ has four sections are laid out in Olson-esque open forms. ‘Justice’ midway through the pamphlet is set out as a miniature playlet with the ‘voices’ of Jurors, here Juror i, Juror iv, and Juror x, alongside ‘Witness: mother’ and finally the Judge. And then there is ‘Sonnet for deficient women’ which is, indeed, a sonnet. The final poem ‘On getting away with it’ is a kind of concrete poem with the line ‘boys will be boys will be boys will be boys will be boys will be’ repeated thirteen times down the page.

Dunning, who is a novelist as well as a poet, imbues the various narrators and narrations in this book with a skillful sense of characterization. So the writing rises off the page in ways that sometimes poetry need not; it is easy to imagine Dunning vividly delivering these pieces. The first section of ‘Girl’ is,

and how did it beginxxxxxx this insidious thing

this convoluted happening

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxwith the taste of metal on my tongue

and how did it feel

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxlike madness

The lack of opening capitalization, the questions in the first and fourth line, the parallel repetitions in lines one and two and the italicized ‘replies’ in lines three and five, all these devices lift the words off the page and into a lived consciousness.

And Dunning uses the repeated motif of the crocodile as the perpetrator in many of the poems, particularly those early more dramatic poems. Here, Dunning is able to use the physiology of the crocodile to great effect. In the third part of ‘Girl,’ the narrator comments, ‘Now, I trace the ruts in my palms, / paper-cut scars left behind by the drag / of his scales. The Crocodile gets his own narration in the second poem in the pamphlet simply called ‘Crocodile.’ In the third section of that sequence, ‘[HOW TO GET THE GIRL: PART 3],’ the persona of the Crocodile comments, ‘Mother told me not to play / with my food but how could I miss / the opportunity to toy with something so delectable?’ In the poem ‘Justice’ the voices of the jurors are shown as providing kinds of psychological excuses for the crocodile’s behaviour, for example, ‘Crocodiles can’t control their reptilian urges, / can’t lessen the lockjawed strength of their bite / or dull their whetted teeth.’

Dunning’s pamphlet has a slight tendency to work with slightly familiar tropes. Eve, for example, is presented as that creator of original sin in ways that ironise her so-called agency. But, as noted above, Dunning’s narrative and dramatic skill has produced a pamphlet with real urgency and bite.

Nicholas Murray’s The Culture Man carries on Murray’s series of verse satires. The Culture Man is written in a variant of the Pushkin stanza, or ‘Pushkin Sonnet.’ Where, Wikipedia tells us, the Pushkin rhyme scheme is: ababccddeffegg, Murray’s variant is ababccddeefggf… whichever; all very fiendish. Where Pushkin used this stanza form for Eugene Onegin, Murray uses his variant to send up the way in which cultural pundits claim to speak for different groups of people. Murray sets up Rupert Vane, ‘from up Notting Hill / whose house has been valued at 3.5 mill,’ whose initial target is Matthew Arnold’s Culture and Anarchy with its definition of culture as ‘the best that has been thought and said in the world.’ And part of Murray’s own satire is, clearly, the need to footnote Arnold as that author. Rupert Vane’s ‘opponent,’ is one Smith-Johnson, recent author of a tome entitled Dumbing Down, which suggests, according to Rupert,

”Let’s all have a slice of the best that’s out there.

We shouldn’t treat art like mass-produced pap

that assumes that the people want stereotyped crap;

that the cultural police, who patronize, claim

is ‘what people want’ though its’s ‘more of the same’.”

The two meet in the tent of a lit fest, where Rupert appears to land the first punches. For Rupert,

People hate the pretentious, the arty, the posh.

They want entertainment and pacy crime thrillers,

not dusty museums with fat cod-Greek pillars

where the walls are all plastered with meaningless tosh.

However, it is Smith-Johnson who carries the day. Rupert’s clearly rather patronizing tone is punctured by Smith-Johnson’s portrayal of himself; ‘My single mum worked at the checkout in Lidl. / At night she read Eliot (George), and James Joyce. / She loved all the poets from Chaucer to Yeats / but also the pub with her boisterous mates.’ And Smith-Johnson’s depiction of the, perhaps, auto-didactic working class is echoed by speakers from the floor, including ‘a cloth-capped ex-docker who leans on his stick,’ who tells the tent that he worked with a man who knew all of Shakespeare and was always ready with a quote. Smith-Johnson’s class identity is echoed by another twenty-year-old speaker from the floor who works in a care home and for whom the statements of ‘these angry old gits / who boss us and tell us they love us to bits,’ are class lies. In the final couplet of the sequence, the girl and the ex-docker join in a kind of chorus, ‘You’re right, lass, we’ll never be bullied or led / for we are The People and we are the power.’

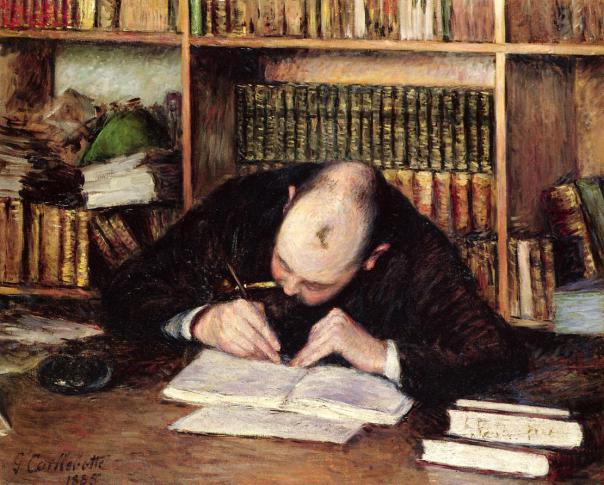

In some ways, as Murray tacitly acknowledges, the Rupert Vane’s of this world are straw men. That wheel has turned and the world of literature is far more open to competing voices than it has ever been. But inside Murray’s skilled sequence, is a portrayal of the working-class reading the classics, which is not only true but perhaps does need reemphasizing. For all of those for whom the review pages are always the first thing they turn to, there are an equal number who don’t need those review pages and to whom those classics still readily speak. My late mother-in-law who left school at 14 re-read War and Peace every year, and my ex-wife still has her mother’s very, very worn Penguin edition.

The theme of dislocation and disorientation in Andrew Neilson’s Summers are Other is indicated by that title. In the opening poem, the sonnet ‘Little Griefs,’ Neilson lists the ‘little’ griefs that punctuate a life, from ‘The hamster buried in the back garden / in a perfume box from Miller Harris,’ to ‘how the small girl who hugged you tightly / now claims her own world and stretches it.’ And Neilson moves these emotions in a very convincing sestet to end the sonnet. The sestet, itself, culminates in ‘but like angels dancing, on their pin, / the little griefs grow great. Then grow again.’

That sense of personal dislocations is continued in the next poem, ‘Corrections,’ with its epigraph, ‘lallation: infantile speech; a speech defect where r is pronounced instead of l (or vice versa). The poem’s first three verses describe a storm and its aftermath, the dislodging of ‘a squab from a nest / […] smeared on the windscreen.’ The squab has ‘the emptied purse of that puckered body; / one eye closed in profile, like a shelled pea.’ The poem then moves into what, the poem suggests, is the childhood of the author, in which ‘a squab myself, I must always recite / the words I’m told to take extra care of, / because life is exacting, shame all round.’

One important thing to note here is Neilson’s very exact and very powerful description of the body of the dead squab. In ‘The Instrument,’ Neilson’s powers of description are used to great effect to describe the interior of a piano that the narrator of the poem has dreams himself inside.

As I waited, subdued in that antique air,

dust gathered on the inward machinery –

the wrest pins and hammers, the tension of strings –

and somewhere something important was keyed

to a small, felt damper of thought.

It’s Neilson’s ability not only to describe with such precision but his ability to swing those particulars into something more metaphysical that makes this a very impressive debut. And Neilson uses those abilities in a range of forms from that first sonnet to the very neatly turned rhyming quatrains of the elegy, ‘The Viaduct.’ In revisiting a scene from his childhood, the narrator in this poem remembers visiting the viaduct with his father’s brother, now dead along with the summers that are ‘other’ in the phrase from the title. The narrator is visiting with his daughter, whom he must teach,

how the viaduct’s span

becomes heartsore and steep.

In the glen’s wooded deep,

I have seen that man.

That last line has a kind of sway of imprecision: does the narrator see the father’s brother, or seen the child as man that he was? But the imprecision opens up those possibilities that also play upon the title of the viaduct which acts as a physical and metaphorical link between childhood and the man as father. It will, in that rather cliched phrase, be very interesting to see what Neilson does next.

*****

Fabrics, Fancies & Fens by Gerald Killingworth. £9.99. Tears in the Fence. ISBN 978-1-9000201-4-5. Reviwed by Sue Kindon

An alliterative title to conjure with, and a geographical clue; this is indeed a symphony in three movements, inspired by significant objects, imagination, and what feels like home territory.

The first section is the shortest, but by no means the least skilful. ‘Fabrics’ suggests the texture of material objects, but also the making or fabrication of things. The opening poem, ’Sambridges’ (‘a comical word for sandwiches used by Private Mason in RC Sheriff’s play Journey’s End’, the footnote informs us) based on the consistency of bread, sets a humorous, homely tone, before deftly twisting to the horrors of the trenches of World War I.

All this from the feel of a simple sandwich. Texture is an all-important starting point, as in ‘Feathered Friends’, with its ‘wispy, plumulaceous’-ness – always good to add a new word to my vocabulary; or in the poem ‘Jack’s Drum’, where the calfskin, from which the drum is fashioned, is described thus:

the surface unblemished

because they kept the bobby calf

apart from scratching wire, ticks –

its baby curls,

the downy pelt of a less than -twelvemonth-old,

scraped, limed,

tanned in bark

‘Fabrics’ concludes with a medley of family stories, carefully observed, humorous, with a bit of nostalgia thrown in.

True magic isn’t ready-made,

we need to conjure it

defying all sorts of gloom

These words from the poem ‘Poundbury Wassail ring true for the second section, ‘Fancies’ – a journey into the realm of the imagination, in which GK explores resonances between the shady area at the boundaries of the ancient world and the present day. Often the way in is through an observation of nature, as in ‘May Morning, Cerne Abbas’, where the approach to The Giant is an ascent through a hillside of cowslips, evoking ‘Celtic war horns’:

the sound too subtle for us

as we climb amongst them

to dance in Summer’s first sunrise.

There is a tantalising sense of the proximity of other, lost worlds, and moments poised on cusp or threshold: ‘…today is the start of almost-Spring’, and ‘That moment before darkfall when – / shadows lose their intricacy’. The imagination is given free reign: ‘There really can’t be any more/ to be said about clouds’ – but GK manages to fantasise with ease, until his musings are brought back down to earth by the intrusion of a plane.

The poetic journey is not limited to Britain – there are also visits to ‘The Ancient Theatre Dodoni’ and ‘An Etruscan Tomb Outside Orvieto’, where the poet unexpectedly and inexplicably finds two green plums. Such places of archaeological interest offer sparks of ly drawninspiration.

There are several beautiful word portraits of women and girls, and the stories and objects associated with them.

Section 3, ‘Fenlandia’, its title a play on words from the well-known piece of music by Sibelius celebrating homeland and freedom, took me into what feels like familiar territory for the writer. The descriptions of Fenland characters and festivals left me wanting more, which can only be a good thing. ‘Flag Fen’ is, for me, the key piece, linking the Bronze Age with modern times. The indented verses refer to the modern age, and I would probably have gleaned this without the preamble. ‘Here one world laps against another’, we are told, and so it does. The initial discovery of worked timbers at the site describes them as ‘history’s bones breaking through their peaty skin’, and the yellow flag irises separate the ancient and modern, mirroring the way the cowslips linked both realms in the Cerne Abbas poem.

The poems mostly follow natural speech patterns. ‘Midnight’ is in the form of 3 Tanka, and there is an ode to the colour brown. A visit to an archaeological site juxtaposes poetic and technical descriptions to great effect. Words have been most carefully selected, each poem pruned to perfection, and as effective read aloud as viewed on the page.

Words from other languages, without footnotes are a slight problem, for example if you don’t read Greek! I can just about decipher the Greek alphabet, so I think I got away with it; and, while we are on Greek words, there is an ekphrastic poem about the long-legged female figures in the paintings of Edward K. Johnson. There are quotations from, and nods to, authors as diverse as Shakespeare, TS Eliot, and Joni Mitchell.

Many poems are a celebration of the old ways, of dancing, drinking, and observing festivities; of breathing the moment, on the verge of discovery. The various themes of the title interweave to create a pleasing texture, where the imagination travels freely, hovering above the wetland landscapes of East Anglia.

These simple words, from ‘Epitaph’, which concludes the ‘Fancies’ section, seem a suitable coda, summarising the challenge for poets of a certain age (self included) in 2026:

So much to put on paper

when an Art

a World

and Ourselves

are dying.

Sue Kindon lives and writes in the French Pyrenees and is currently working on a bi-lingual collection.