*****

Sudeep Sen’s [www.sudeepsen.org] prize-winning books include: Postmarked India: New & Selected Poems (HarperCollins), Rain, Aria (A. K. Ramanujan Translation Award), Fractals: New & Selected Poems | Translations 1980-2015 (London Magazine Editions), EroText (Vintage: Penguin Random House), Kaifi Azmi: Poems | Nazms (Bloomsbury) and Anthropocene: Climate Change, Contagion, Consolation (Pippa Rann). He has edited influential anthologies, including: The HarperCollins Book of English Poetry (editor), World English Poetry, and Modern English Poetry by Younger Indians (Sahitya Akademi). Blue Nude: Ekphrasis & New Poems (Jorge Zalamea International Poetry Prize) and The Whispering Anklets are forthcoming.

Sen’s works have been translated into over 25 languages. His words have appeared in the Times Literary Supplement, Newsweek, Guardian, Observer, Independent, Telegraph, Financial Times, Herald, Poetry Review, Literary Review, Harvard Review, Hindu, Hindustan Times, Times of India, Indian Express, Outlook, India Today, and broadcast on bbc, pbs, cnn ibn, ndtv, air & Doordarshan. Sen’s newer work appears in New Writing 15 (Granta), Language for a New Century (Norton), Leela: An Erotic Play of Verse and Art (Collins), Indian Love Poems (Knopf/Random House/Everyman), Out of Bounds (Bloodaxe), Initiate: Oxford New Writing (Blackwell), and Name me a Word (Yale).

He is the editorial director of AARK ARTS, editor of Atlas, and currently the inaugural artist-in-residence at the Museo Camera. Sen is the first Asian honoured to deliver the Derek Walcott Lecture and read at the Nobel Laureate Festival. The Government of India awarded him the senior fellowship for “outstanding persons in the field of culture/literature.”

*****

Omar Sabbagh on Sudeep Sen’s Anthpocene

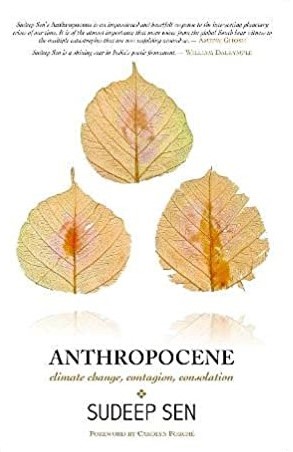

Anthropocene: Climate Change, Contagion, Consolation by Sudeep Sen. £19.99. Pippa Rann Books & Media in Association with Penguin Random House. ISBN 978-1-913738-38-9

1.

‘The idea of “white” space has always been important to me,

both in my art and in my living….

In white we have the entire spectrum of colour and beyond,

beyond infrared and ultraviolet.’

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx–S.S., ‘Poetics of Solitude, Songs of Silence’ [p. 162-164]

‘… Under your feet,

the imagined bowl of blue

light sustains you, me,

and us.’

xxxxxxxx–S.S., ‘Meditation’ [p. 171.]

Sudeep Sen’s latest work, Anthropocene, is subtitled, Climate Change, Contagion, Consolation; and while it is a work replete with a poetic manner and reach which readers of Sen past will recognize as new and vintage ‘Sen’, it is also a work that evidently, purposively, has been configured to address a dovetailing set of communal concerns besetting, if not besieging, the world in its current dire state. And though the title and its subtitles do indeed outline or signpost a sort of poetic agenda or vision which streams through the book, the committed nature of the work is not pat politics or politicization. Primarily, because the deeply personal mixes with the mythic at times, and with, as well, the contemporary world’s most pressing and indeed universal dilemmas. Featuring formal and free verse forms, and a variety of prose modes (intimate diary, micro-fiction, prose poems, reportage), there is a doubling act in this book which is salutary: the artist’s native solitude is mapped onto the rigorous calling to (as the Prologue’s title has it), ‘not look away.’

Elsewhere Sen cites Brecht (one of a few Brecht-citations) questioning if there will still be song in ‘dark times’: answering, yes, there will be, about, precisely, the dark times. Indeed, the two epigraphs to the eponymous, second partition of the book, ‘Anthropocene: Climate Change’, are from Yeats’s ‘Easter, 1916’ and Derek Walcott’s Tiepolo’s Hound: and the paradox of Yeats’s ‘terrible beauty’ is ranged with ‘an altering reality for vision’ in which Walcott speaks of his ‘little strokes’, ‘syllables’, as being ‘not just his own.’ This double citation holds doubleness in each of its sides. New, pressing realities are terrible, but then beautiful, and are spoken-to in an artist’s own words whose ownership are, by that last token, immanently as much as imminently shared. For as in the later entry, ‘May Day’, in today’s world, ‘May Day’ is ‘every day.’ Or then, in one of the book’s most signal entries, ‘Love in the Time of Corona’ (a poem that has been translated already into several languages, and shared thereby), the reference to Gabriel Garcia Marquez is made doubly telling. In the pertaining epigraph Marquez is seen to say that he doesn’t believe in God, but is scared of him. This paradox, thus, a bit like the contagion of the Covid-19 pandemic: something incredible by way of its insidious and sheer invisible nature, but for all that, something to fear, deeply. Telling duality abounds.

So, when towards the end of the book, in a prose entry titled, ‘Poetics of Solitude, Songs of Silence’, Sen writes that he has ‘never needed external causes to internalize and live life solitary and indoor’ (a note paralleled earlier in the book’s Prologue as well), we alight on a sentiment that seems in context to hold another sense of paradox. In a time when the world is forced to a certain extent into mutual isolation, the introverted artist who requires solitude and silence in any case, suddenly becomes the icon of the universal condition. So that, in ways I hope to illuminate, solitude and solidarity map and/or dovetail across the meaningful purports of this book. The committed nature of the thematic contents can be seen to be engagements of an artist whose sensitivity is dual: there is the sense of sensitivity as emotionality, lived-out in many visceral and violent ways in the book’s responsive images at times, and there is the sense of the sensitivity of one who permits himself retreat. Between suffering and consolation, between the visceral violence of ‘pollution and co-morbidities’ and the delicate lyricism of personal observation and sentiment, the work can be called, in short, a work of sensuality. The skyscapes of solitude are limned at the same time as the different kinds of earthed solidarity that are engendered, necessarily, by extreme circumstances.

Indeed, this dual vision is embodied in some of the opening paraphernalia of the book as well. After the dedication, the book’s overall epigraph is verse in the original Bengali of Sen himself, and then the same in English translation. The wish for rain as ‘the only truth’ in this verse is both local, we assume, to the ‘steaming skies’ of the Asian subcontinent and holds, too, philosophical redolence as an image of the universal yearning for the gifts of flourishing. The local and the global marry in this formal opening to the book. And as with Sen’s previous major work, Fractals, the term ‘anthropocene’ is parsed at the opening as well, from the dictionary, a technical word that works as both noun and adjective. Its meaning (the world in the era of human dominion) aside, I do think that the act of defining a somewhat technical term (in a book that like much of Sen’s work uses images from the hard(er) sciences) is another instance of bifocality. The word is strange enough to need definition, perhaps, but also in being defined by the dictionary in all its detail, is shown to have groomed heritage. The old and the new, marrying thus, too. And the very opening of the book (after the prose ‘Prologue’) dedicated ‘for Aria’, Sen’s son, follows suit in being titled, ‘I.E. [That is]’. A very delicate lyric accumulates in this poem, aping a form of premise followed by inference. In three staggered stanzas, the apostrophized hears ‘the sea’ in ‘a lone rustling leaf’, then because his father considers ‘the sea silent’, the beloved hears the sea’s silence in his father’s ‘studio.’ And because of that, ‘the silence will not empty / the sea / of its leaves.’ This loving parody of an almost axiomatic kind of reasoning, about particular observations, intimates the world in toto in the way that wholly discrete and disparate elements are made to magically cohere (foreshadowing the ‘pages’ of watery flow to follow). And such oneness is deeply apposite to the way a father loves his son, or, if you like, thinks the world of him.

And in a final note on some of the formal tics of the work which are indicative of Sen’s sensibility, the vast majority of the book uses epigraphs at different levels (book-wide, for partitions of the book, and above individual poetic entries) and dedications in a layered and composite, near-configurative way. Many a time a citation or citations (from the likes of, say, T.S. Eliot, Derek Walcott or Fiona Sampson, among others) will even be woven into individual poetic entries – quotes not just signposting, thereby, a theme or outlining a stance on things above the beginning of the individual work. This not only shows poetic solidarity with famed poets and thinkers, past and present, the implicit invoking of an imagined or ideal community of poetic responses to dark times, but is also, in the very act of this, showing just how much a poet’s readerly solitude can be an avenue onto the world. While not wanting to ‘look away’ as a responsive literary artist, Sen can often build his sense of commitment and solidarity from the ‘study’ he details as his bower in the ‘Prologue’. In this sense, solitude and solidarity can become each other in the artist’s hands, eyes, and human dominion, a dwelling, domicile.

Perhaps it’s no accident, thus, that in the eighth, penultimate partition of the book (before the ‘Epilogue’), ‘Lockdown’, the acts of ‘reading’ and ‘writing’ prove central to the titles and entries there. At the close of a late entry of three linked haiku, ‘Handwriting’ (dedicated ‘for Michael Ondaatje’) ‘letterforms and words / bloom, come alive – spell.’ This has something of the textual punning magic of the famous ending of Elizabeth’s Bishop’s ‘One Art.’ Writing well can cast good, assisting spells. Indeed, just a little further back, a single haiku, ‘Ash Smoke’ tells a similarly strangely hopeful tale:

xxxsomething still remains –

xxxotherwise from ashes, smoke

xxxwould not rise again

xxx–S.S., ‘Ash Smoke’ [p. 152.]

But before we get to the ‘Consolation’, the main bulk of the book preceding is about (and about) the difficult journey towards the earning of such redress.

2.

‘Speaking in Silence’, a poem dedicated for ‘Fiona’ (Sampson), not only interweaves strategically-placed citations of the latter’s recent collection, Come Down, but for all its solidarity, whereby the poet is ‘certain we will continue walking, together and alone, / now and in the life-after’, still, it questions in a metaphysical manner that indicates the ultimate solitude of the poetic voice. ‘…. Shall we return to aleph’s source, / to oxhead’s hieroglyph, to fountainhead’s genesis’; ‘… Are we on a robotic treadmill, / on a journey mapped out for us?’ The ‘us’ here tallies with both the ‘together’ and the ‘alone’ of above; with both the immediate, shared reality, and the broader existential predicament. This ‘dialogue-poem’ alludes to and works as a musical duet, a jugalbandi — music (in addition to poetry) being an important interest of both the poets at hand here.

Close-by, in a series of haikus, ‘Corona Haiku’, small and overt metaphysical entries are equally potent and vocal. Whether it’s the ‘havoc’ of the ‘virus’s vatic’ (‘Covid 19’), or the questioning in ‘Pandemic 1’, ‘will we find a more / compassionate world, after / this pandemic’s death?’, or in ‘Death’, the ‘dread of death, death of / loneliness – our choices / out of our hands’ – the answers are never definitive. Such is the solitude of a shared condition, a shared condition that, existentially, may have always been the case, but that in the contemporary climate is dearly intensified. In the third part of the long prose entries of ‘Black Box: Etymology of a Crisis’, titled, ‘There After: Memory, Will’, the philosophical register abounds, achingly:

xxx… All night I dream in fragmented images. Memory plays tricks with my mind. Her story, xxxhis story, my story, history – all collude and collate.

xxxThe trailer I saw before was only a glimpse. The film is still being cut. We might yet xxxchange the narrative. But do we have control over destiny or karma’s fate?

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx–S.S., ‘Black Box: Etymology of a Crisis’ [p. 68-75.]

These are questions we all ask in loneliness, but questions, again, that seem to redouble in interest and depth in today’s crises-ridden world. After all, the contingencies of money and power, which might have proved screens before our crises-ridden era, aren’t quite protection anymore from the development of ‘global warming’ or ‘contagion’ and other ‘co-morbidities.’

Just so, in an early entry, ‘Disembodied’, we now live in a world where the body is ‘carved from abandoned bricks of a ruined temple’, a reality where the body is ‘worshipped, not for its blessing, / but its contour.’ And we end this disembodying experience ‘directionless – looking for an elusive compass.’ As the closing strophes of the ‘Prologue’ have it poetic form like bodily form is witnessing ‘our world’s passage from utopia to dystopia.’ And this kind of alienation is also perhaps, if not as overtly effected as in Brecht, an alienation effect aimed to wake the reader (via the disorientation) to our present losses. Much later in the book, in the now-reprised title, ‘Disembodied 3: Within’, we end with ‘Life’s dance continues – with or without us – / only in the understanding of what is, / is there freedom from what is.’ By this time, we are nearing the ‘Consolation’ part of the book, so the transience of the bodily life, souped-up in today’s world, is beginning to be redressed. And this last italicised quote (from the philosopher, J. Krishnamurti) does indeed epitomize the effect of the whole book: there is only hope for returning to a more poetic world, we might say, by not looking away, by squarely facing the loss of bodily life, in order, thereby, to learn in wisdom and transcend. Life’s dance continues, after all, even if, to quote Auden, ‘the Old Masters were never wrong,’ ‘About suffering.’

All this said, the solitudes of the poet’s recognitions are also at times soliloquies in or of solidarity. In one of a few entries in the book which either by titular conceit and epigraph or by attitudinal tone (one of prosy reportage) indicate the book’s committed ethos, ‘Obituary’, we read of the ‘Death knells’ as they ‘peal’. And though with, ‘Another sick, another dying, / another dead –’, yet, ‘yes, they were us.’ It’s not just the thematic of solidarity, humanistic in the sense that the wretched of the earth are connected to each one of us blessed with the current privilege of health, but that that last italicized entry is a quote from ‘The New York Times’ epigraph. In the very set-up of the poem then, some fanciful notion of the role of poetry as escape (looking-away) is abjured in favor of its role as a ‘daily’ wake-up call. The diary-like entries of the nearby ‘Newsreel’ open, after citing Brecht’s ‘When Evil-Doing Comes Likes Falling Rain’, at ‘9 am: Morning News’ with:

xxxAt nearly 50ºC, you do not need a pandemic to remind you of human agony and grief – xxxyou inhabit me.

xxxDaily death toll rises, coronavirus continues to inflate, inflect. Enforced lockdown, xxxinhuman laws – weary migrants, hungry die on the highways.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxx–S.S., ‘Newsreel’ [p. 66-67.]

Those being, literally, disembodied, those bodies, as the early ‘Disembodied’ has it, we’ve seen, ‘carved from abandoned bricks of a ruined temple’, are also, we continue the verse here, ‘from minaret-shards of an old mosque, / from slate-remnants of a medieval church apse, / from soil tilled by my ancestors.’ In the midst of ruination, death and suffering, there is, it seems, the shared earth of consanguinity, humanity. It’s not for nothing that in the final, ninth partition of the book, the ‘Epilogue’, the three entries are: ‘Meditation’, ‘Prayer’ and ‘Chant.’ In the first of these ending-poems we end on: ‘Eyelids veiling / our pupils, see – a sense / of calm, peace, love.’ The pupils here are not just the poet’s two, but of all us, students of suffering. Recalling the earlier mention of ‘white space’, the ending of ‘Prayer’ speaks about how: ‘Five colours mix – / white.’ Equally, though, in ‘Chant’ following, closing the book, ‘black contains / everything’ and ‘all is one – // one is many – // many is all.’ So, while (still with ‘Chant’) it’s sad in today’s world that ‘everything contains / nothing –’ and that ‘nothing contains / all’ – such inverting truths about a denuded earth, a topsy-turvy world, as woken-up to, can only be or may prove to be signs of waking health. One hopes.

Indeed, to compound the black and the white of all of it, we read in ‘Summer Heat’ prose entries like: ‘No moisture, just steam, heat, heat, and more heat. Barren. Everything seems in short supply, except heat’. A bit later though, in ‘Shower, Wake’ we learn how: ‘With or without water, in flood or drought the existence here remains unchanged.’ This kind of yin-and-yang typifies many of the oppositional motifs that form and configure the staggered graces of Anthropocene. And if the opening epigraph of the whole book (mentioned above) from Sen in original Bengali and then Sen in his own English translation, yearned for the gift of rain, and of human flourishing, perhaps after all it is because of its ultimate simplicity, its black and white. Simply put, we are all so alone – absolutely together, ultimately, only in that equal solitude before nothingness. In ‘Rain Charm’ we’re given a ricocheting image, simply put, of the idiosyncrasies of our communal concerns:

xxxRain has a special seductive appeal – its innocuous wet, its piercing strength, its gentle xxxdrizzle-caresses, its ability to douse and arouse. The entire charm lies in its simplicity.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx–S.S., ‘Rain Charm’ [p. 46.]

3.

In his ‘Prologue’ Sen claims this work as a ‘quiet artistic offering’. However, it is filled with alarums and bells performed by many visceral and violent images, emergent from the bodily realities of a blighted world. That said, combining the two, ‘Ganga Rising’ I think phrases the conundrum of the solitary poet excellently, as he needs must turn responsive, responsible, rising to the challenge – not to look away:

xxxHere, there is no space for perfectly rounded pebbles or gentle musings – only large xxxgranite outcrops can shackle the soul’s ferocity – a jagged fierceness – not harsh, yet xxxquietly robust.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx x–S.S., ‘Ganga Rising’ [p. 138.]

The imagery from the ‘ganga’, so indicative of Sen’s native climates, is still in concretion and as metaphor universal in its river-ing reach. We can recognize poetry in the world only by recognizing and rising to that same world’s (now) deep-set imperfections. Even if Sen claims to be ‘quiet’ here in this timely book – it might be more apposite to say that he is also in many evident ways ‘quietly robust’.

Omar Sabbagh is a widely published poet, writer and critic. His latest books are Minutes from the Miracle City (Fairlight Books, 2019), Reading Fiona Sampson: A Study in Contemporary Poetry and Poetics (Anthem Press, 2020), and To My Mind Or Kinbotes: Essays on Literature (Whisk(e)y Tit, 2021). His fifth poetry collection, Morning Lit: Portals After Alia, is forthcoming in early 2022 with Cinnamon Press. Currently, he is Associate Professor of English at the American University in Dubai (AUD).

*****

Sudeep Sen: Disembodied 1, 2 & 3

DISEMBODIED

1.

My body carved from abandoned bricks of a ruined temple,

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx from minaret-shards of an old mosque,

xxxxxxxfrom slate-remnants of a medieval church apse,

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxfrom soil tilled by my ancestors.

My bones don’t fit together correctly xxxxxxxxxas they should —

the searing ultra-violet light from Aurora Borealis

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxpatches and etch-corrects my orientation —

magnetic pulses prove potent.

My flesh sculpted from fruits of the tropics,

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxblood from coconut water,

skin coloured by brown bark of Indian teak.

My lungs fuelled by Delhi’s insidious toxic air

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxecho asthmatic sounds, a new vinyl dub-remix.

Our universe — where radiation germinates from human follies,

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxwhere contamination persists from mistrust,

xxxxxxxwhere pleasures of sex are merely a sport —

where everything is ambition,

everything is desire, xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxeverything is nothing.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxNothing and everything.

2.

White light everywhere,

xxxxxxxbut no one can recognize its hue,

no one knows that there is colour in it — xxxxxall possible colours.

Body worshipped, not for its blessing,

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxbut its contour —

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxartificial shape shaped by Nautilus.

Skin moistened by L’Oreal

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxand not by season’s first rains —

skeleton’s strength not shaped by earthquakes

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxor slow-moulded by fearless forest-fires.

Ice-caps are rapidly melting — too fast to arrest glacial slide.

xxxxxxxIn the near future — there will be no water left

or too much water that is undrinkable,

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxexcess water that will drown us all.

Disembodied floats,xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxafloat like Noah’s Ark —

no GPS, no pole-star navigation, no fossil fuel to burn away —

xxxxxxxjust maps with empty grids and names of places that might exist.

Already, there is too much traffic on the road —

xxxxxxxxunpeopled hollow metal-shells xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxwithout brakes,

swerve about directionless — xxxxxxxxlooking for an elusive compass.

*

New Delhi

* * *

DISEMBODIED 2: LES VOYAGEURS

for Bruno Catalano

To understand yourself, you must create a mirror

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxthat reflects accurately what you are ….

Only in the understanding of what is,

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxis there freedom from what is.

— J KRISHNAMURTI

Bronze humanforms sculpted, then parts deleted —

xxxxxxxas if eroded by poisoned weather, eaten away

by civilisational time —

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxcorrosion, corruption, callousness.

Power, strength, gravitas residing in metal’s absence.

Men-women, old-young, statuesque —

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxholding their lives in briefcases —

xxxxxxxxxincomplete travellers,

Marseilles les voyageurs, parts of their bodies

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxmissing —

surreal —xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxsteadfast, anchored.

Engineered within their histories

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxof migration, travel — over land, by sea —

coping with life’s mechanised emptiness.

Artform’s negative space or positive? What are we too see?

xxxxxxxxHave these voyagers left something behind,

or are they yearning

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxto complete the incompleteness

in their lives?

xxxxxxxxThey are still looking —

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxas am I, xxxxxxxsearching within.

Marseilles, France

* * *

DISEMBODIED 3: WITHIN

for Aditi Mangaldas

You emerge — from within darkness, your face

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxsliding into light —

you squirm virus-like in a womb,

draped blood-red,xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxon black stage-floor.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxAround you, others swirl about

dressed as green algae,

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxlike frenetic atoms

xxxxxxxxunder a microscope in a dimly lit laboratory.

Art mirroring life — reflecting the pandemic on stage.

Your hands palpitate,

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxas the sun’s own blinding yellow corona

cracks through the cyclorama.

xxxxxxxxPeople leap about — masked, veiled.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxYou snare a man’s sight

with your fingers mimicking a chakravavyuh —

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxyou are red, he is green, she is blue —

trishanku — life, birth, death —

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxregermination, rejuvenation, nirvana.

Everything on stage — as in life —

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxmoves in circular arcs.

Irises close and open, faces veiled unveil —

xxxxxxxxhearts love, lungs breathe — breathless.

Lights, electromagnetic — xxxxxxxknotted, unwrapped —

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxmusic pulsates, reaching a crescendo,

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxthen silence.

Time stops. Far away in the infinite blue of the cosmos —

xxxxxxxxxI look up and spot a moving white.

I see a white feather

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxtrying its best to breathe

in these times of breathlessness, floating downwards —

and as it touches the floor, in a split-second

everything bursts into colour, movement, the bols/taals

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxtry to restore order,

rhythm, xxxxxxxxxxxboth contained and free.

The backdrop bright orange,

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxthe silhouettes pitch-black.

As you embrace another humanform,

xxxxxxthe infinite journey of timelessness might seem

inter_rupted,

but now is the moment to reflect and recalibrate

immersed in the uncharted seas, in the widening circles,

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxtelling us — others matter,

the collective counts.

I examine minutely the striated strands

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxof the pirouetting feather, now fallen —

its heart still beating, its blood still pumping,

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxits white untarnished.

Life’s dance continues — with or without us —

only in the understanding of what is,

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxis there freedom from what is.

New Delhi

Disembodied 1, 2 & 3 taken from Anthropocene: Climate Change, Contagion, Consolation

PIPPA RANN BOOKS & MEDIA (UK) in association with PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE

£19.99 | €24.99 | $29.99 | Rs.599 (hardback) | 2021 | Pages 176 | ISBN 978-1-913738-38-9

* * *

Reblogged this on The Wombwell Rainbow.

LikeLike