*****

Michael Hofmann: One Lark, One Horse • Peter Robinson: Ravishing Europa • Robin Thomas: Momentary Turmoil • Sarah Corbett: A Perfect Mirror • Michael Curtis: Family Likeness • Jessica Mookherjee: Flood • Josephine Balmer: Letting Go: Thirty Mourning Sonnets and Two Poems • Derek Sellen:The Other Guernica • Michael Bartholomew-Biggs : Poems in the Case

Chapbooks

Helen Ivory: Maps of the Abandoned City • Peter Raynard :The Combination

Reviewers

Edmund Prestwich • Andy Houwen • Michael Loveday • Mike Farren • Derek Sellen • William Bedford • Emma Lee • Alison Jones• Belinda Cooke• Fiona L. Bennett • James Roderick Burns

*****

Michael Hofmann’s One Lark, One Horse reviewed by Edmund Prestwich

One Lark, One Horse by Michael Hofmann. £14.99 (hardback). Faber & Faber. ISBN 9780571342297

Immediate attractions of One Lark, One Horse are the poet’s sharp intelligence, spectacularly fine lexical sense and mordant wit, as in the opening of “Cricket”:

Another one of those Pyrrhic experiences. Call it

an expyrrhience. A day at Lords, mostly rain,

one of those long-drawn-out draws so perplexing to Americans.

Creating the illusion of headlong, spontaneous speech, Hofmann’s assured control of rhythm and syntax makes puns, images and ideas seem to ignite almost incidentally. The tone keeps changing, and different perspectives play into and out of each other, but it’s all held together by the sense of a single mind running through a swerving arc of thought as it responds to the weirdness of the English attachment to cricket. At one extreme it speaks of the English as if from the viewpoint of a foreign anthropologist, drily exaggerating established stereotypes –

Did I say it was raining, and the forecast was for more rain?

Riveting. A way, at best, for the English

to read their newspapers out of doors and get vaguely shirty

or hot under the collar about something. The paper, maybe, or the rain.

However, things turn at the midpoint of the poem – “And yet there was some residual sense of good fortune to be there” – after which the speaker clearly identifies himself as one of the tiny English crowd , sharing their reactions even as he views them with quizzical detachment. That’s a return to the perspective of the beginning, where he speaks of Americans from an English point of view (the pun on “expyrrhience” assumes an English voice imitating an American accent). What makes the mind of the poem so interesting, in other words, is not just its speed and intelligence but its ability to see both other things and itself from rapidly changing angles.

This ability is connected to the facts of Hofmann’s life, which have made him almost but not quite at home in different cultures. Born in Germany, the son of a famous German novelist, he moved to England at four and was educated here through school and university but – I think I read somewhere – continued to speak German at home. He has spent his adult life as a prolific translator from German, and much of it teaching in American universities. And there’s something deeper too. In a Paris Review interview in 2014 he said,

If Kafka hadn’t said it, then I would say it—“literature, from which, or out of which I am composed.” Perhaps I’ll say it anyway, echoing Kafka. When my father’s first book appeared, I was twenty-one or so. I called it his firstborn, in a poem written not long after. We defer to print, where I’m from. Quite soon, I’ll be like that Archimboldo painting, all book.

He straddles cultures, in other words, not only in space but also in time. We all do to some extent, but someone so profoundly bookish does so to an unusual degree.

Being an almost insider who’s also an almost outsider gives a peculiar double penetrativeness and also dividedness to Hofmann’s cultural gaze. In “Cricket” and many other poems the result is a combination of forcefulness and uncertainty which I find deeply attractive. My favourite poems in the book are those in which Hofmann seems bewildered not only by something outside himself but also by his own responses to it.

Not everyone will feel the same. Some greatly admire satirical poems such as “Portrait d’une Femme”, which is about the shallowness of celebrity media culture. This makes a splendid display of Hofmann’s rhetorical weaponry. To my mind, though, it views its subject too purely from outside, pitting pop culture against the high culture of Ezra Pound. The title copies that of Pound’s portrait of a society hostess who has no self beyond bits and pieces she’s picked up from others – “Your mind and you are our Sargasso Sea,” as Pound puts it. Hofmann’s epigraph is a quotation from Pound’s “Hugh Selwyn Mauberley” – “The age demanded an image / of its accelerated grimace”. As in Pound’s “Portrait”, Hofmann’s title is ironic: his target has no imaginary presence beyond the media forces she channels. That’s the point, you might say, but as in Pound’s poem I think it limits our engagement. The writer’s gifts are vividly displayed in a flood of biting characterisations and clacking, clattering or hissing syllables, but in the end it’s all too single-minded not to become boring before the foam has finished running up the beach.

What a contrast with “Valais”, about the canton in Switzerland where Rilke finished the Duino Elegies. Where satirical poems like “Portrait” or “Venice Beach” seem to speak from a position of scornful superiority “Valais” speaks out of and draws the reader into a volatile contemplation of blending, disruption and change. Instead of pushing one line of thought through, as the satirical poems do, it creates a fluid mosaic of statements in which each releases ripples of suggestion and all enter into multiple relationships with each other. It sets you thinking and imagining for yourself, rather than just receiving the poet’s attitude. Take the stanza

Smells of hay and dung, the murmurs of subtle conversation.

Next door are tax-efficient sheep.

The underground chicken palace like CERN

Or a discreet gun emplacement.

The lights come on when we appear and go off after we’re gone.

The satirical potential of the second and third of those lines is obvious, and in a lesser poem might have been systematically developed. Here, their acerbity is just one element in a swirl of responses and reflections. For one thing, irony is offset by the pastoral peace of the first line. For another, across the second line there flashes the delightfully absurd idea of the sheep as neighbours in the human sense, good at compiling their own tax returns. For another, the peacefulness of the first three lines contrasts with what’s earlier been said about the violent history of a crossing point that was once the site of threatening castles and the route of Hannibal’s and Napoleon’s armies . Better unromantic calculations of tax advantages than armies in transit or predatory feudal lords keeping an eye on trade routes, even if the fourth line does hint that preparedness for war still underlies our peace. I’m not sure what the chicken palace is – I picture a glittering, nightmarish battery farm in which chickens become not much more than biomachines tended by white gowned workers – but its associative collision with CERN sets off trains of thought about the positive and negative aspects of the scientific approach to life… The hadron collider itself is a dramatically extreme symbol of the processes of interaction and change previously suggested by the image of the Rhone as a conduit of trade, by the line about “the island exporting itself to its neighbours one barge at a time” and by the beautifully paradoxical description of the valley as “a place of through” (my italics). Such processes, in other words, relate to fundamentals of existence.

I could go on. In this poem of endlessly changing shimmers of suggestion you can’t start disentangling threads without feeling the absurdity of stopping at any particular point. There are many other suggestions in the stanza I’ve just discussed, let alone in the poem as a whole. As far as the rest of the poem is concerned, I’ll just make two more observations.

First, Hofmann’s wordplay is present in a more subdued manner than in “Cricket”, but no less effectively for that. “Poplars were planted en passant by Napoleon’s Grande Armée” is magical in the way one phrase both contains and dissolves the earth-shaking literal passage of the army: as they passed through they incidentally planted the poplars. In a sense Hofmann could have effected the same play on words by writing “in passing” or “by the way”, but because in English “en passant” refers to a chess move or is an elegant way of saying “incidentally”, suggesting a fleeting change of direction in what someone says, it transforms violence into peace far more radically.

Second, this poem shares concerns of the volume that I haven’t focused on: poems that seem to reflect, sometimes directly, sometimes obliquely, on Hofmann’s own life and aging, and to take stock of his achievements. Some are extremely brief, but there’s a special poignancy to this group. “Valais” is both light and subtly poised in the way it touches on the theme. All its images seem fraught with implicit symbolism or to carry an indefinite weight of synecdoche. So “The lights come on when we appear, and go off after we’re gone” is both another reference to the very modern, technological nature of this pastoral and a reflection on mortality, connecting with the closing lines, which allude to Rilke’s desire to die at Muzot castle in the Valais:

Who wouldn’t want to die in a thirteenth-century tower

With light sensors and cold running water

Off the hills and a chill in the sunny air of the contemporary archaic.

Altogether, this is a book I strongly recommend for the pleasures of fine-honed craft and the way its distinctive voice takes the language in new directions.

Edmund Prestwich is a retired English teacher. He organises poetry discussion groups, tutors for the Poetry School, works on the committee of Poets & Players to promote performances of poetry and music in Manchester, writes reviews and writes poetry. His two collections are Through the Window and Their Mountain Mother. He blogs at http://edmundprestwich.co.uk/

******

Peter Robinson’s Ravishing Europa reviewed by Andy Houwen

Ravishing Europa by Peter Robinson, £10. Worple Press. ISBN 9781905208432

Ravishing Europa both celebrates the rich inheritance of openness to other cultures and languages and laments the ‘patriotic scoundrels’ who refuse it for spurious reasons; as its title implies, Europe is both ravishing and being ravished. Behind Brexit lies this more longstanding tension, one that has also manifested itself in British poetry. When Philip Larkin was asked if he read any ‘foreign’ poetry and famously replied ‘Foreign poetry? No!’ Charles Tomlinson criticised Larkin in the same set of interviews as ‘a symptom of that suffocation that has affected English art since Byron’ and argued for more acceptance of influences from abroad: ‘I couldn’t see why we shouldn’t have […] Apollinaire, Picasso and Paul Klee’. The notes at the back of Ravishing Europa claim Tomlinson ‘would probably […] have voted “leave”. In its allusions to, among others, Apollinaire, Heidegger, Montale, Nooteboom, and Sereni, though, this collection demonstrates the receptivity to a wider array of inspirations for which the younger Tomlinson, at least, advocated.

The allusion to Apollinaire appears in the especially touching opening poem, ‘Belongings’, dated 3 April 2016, in which the poem’s ‘we’ encounters ‘two Belgian girls’ travelling through Europe. The two groups’ languages mingle: the poem’s ‘we’ wishes them ‘Bon vacance!’ in broken French and the Belgian girls reply in English, ‘You too!’ The pathos of ‘Belonging’ depends on the reference to the poem the girls read, Apollinaire’s ‘Le pont Mirabeau’. Its speaker mourns the passing of time, as ‘Sous le pont Mirabeau coule la Seine / et nos amours’. The ‘confetti of magnolia petals / scattered over mossy lawns’ in ‘Belongings’ thus come to suggest the vulnerable transience not only of that instance of kindness but also, potentially, of young people’s opportunities to live and travel so freely in Europe and feel that they, too, can belong there, in the rebuilt homes of its ‘post-war years’.

The collection does not, however, merely replace a narrower patriotism or ‘belonging’ with a slightly altered one that stops abruptly at the Urals. The origin of the word ‘Europe’ to which the collection’s title alludes does not, of course, come from within what most would now think of as Europe’s borders. In the Ovidian tale, Europa, ravished by Zeus in the form of a bull and brought by him across the sea to Crete, is from Phoenicia, where the Syrian conflict still drags on. Robinson’s oeuvre – his poetry, translation, and literary criticism – urges us to avoid drawing up simplistic boundaries. This is no less true of the collection’s conception of Europe: instead of an enlarged patriotism, it depicts a far more expansive notion of openness to others that does not impose such rigid borders. As the speaker in ‘Where Europe Ends’ puts it (a title that responds to the German-Japanese writer Yoko Tawada’s story ‘Where Europe Begins’), ‘there is no end to Europe’.

This open-ended understanding of the concept of Europe is evident in the haunting parallel between the Europa legend and the plight of Syrian refugees in ‘On a Walk to Sonning’. The poem takes as its epigraph that Sonning resident Theresa May’s infamous assertion on 5 October 2016 that ‘If you believe you’re a citizen of the world, you’re a citizen of nowhere’. Such callousness not only encourages the refusal to give refuge to the most vulnerable from today’s war-torn countries; it also denies the way in which the crude distinction between ‘local’ and ‘foreigner’ ultimately applies to none of us:

we’re vulnerable transients, all of us,

so near yet far off littorals,

Europe’s shores on which to lodge –

or rescued from the mid-sea waves

in need of shelter, safe house, home,

and who are you to judge?

Just as, in Golding’s Metamorphoses translation, Europa was taken by Zeus ‘Amid the deepe’ of the Mediterranean, ‘where was no meanes to scape with life away’, those fleeing the war, rape, and torture of modern-day Syria are likewise forced to cross those same perilous waters.

Ravishing Europa is thus a collection that does not cut off its sympathies at any cultural or geographical border. The double sense of the joyful moment of human connection in ‘Belongings’ and the retrospective knowledge of its giving way to these darker times encapsulates the finely balanced ‘in-two-minds’, as ‘Belongings’ has it, of the collection as a whole. It is both a paean to and an elegy for a time soon to pass not just of a closer affinity between Britain and the continent, but one when the idea itself of closer affinity to cultural others seemed to be something to which we were all moving inexorably nearer, not further away.

Andrew Houwen (1985-) is a translator of Dutch and Japanese poetry and is currently a JSPS post-doctoral fellow at Tokyo Woman’s Christian University. He performed his translations of the prize-winning Dutch poet Esther Jansma with her at the 2013 Reading Poetry Festival. These were subsequently published in Modern Poetry in Translation and Shearsman. His and Nihei Chikako’s translations of the modern Japanese poet Naka Tarō will be published with Isobar Press in the near future.

*****

Robin Thomas’s Momentary Turmoil reviewed by Michael Loveday

Momentary Turmoil by Robin Thomas. £8.99. Cinnamon Press. ISBN: 978-1788640077

Robin Thomas’s debut book Momentary Turmoil is that rare thing in poetry these days – a genuine jambalaya, or miscellany. The collection has been sequenced in a way that intentionally tumbles into assortment poems that otherwise – by other poets – might be organised into discrete sequences. This contributes to a feeling of multiplicity, accentuating the impression of Thomas’s already varied range.

The book is indeed a rich, sustaining feast, and its dominant ingredient, arguably, is ekphrastic poetry. There are ten such poems here, responding to European paintings from the past several centuries. (There are also four poems relating to the Second World War, four about music (particularly jazz), three about an elderly mother, and several relating to transport, among a number of others on diverse subjects.)

The dispersal of the ekphrastic poems modestly plays down the sheer invention of Thomas’s technique. Each one of these ten poems adopts its own method. Only rarely does Thomas rely on a description of the static painting as aesthetic object. ‘Excursion’, for example, presents a surreally imagined entry into (i.e., inside) the painting:

I’m through the Gallery doors, heading

for L’allée à Chantilly which I enter

to find myself under its frondescent canopy.

[…] I slip

Another is a monologue by the portrait’s subject addressing the reader:

Look then,

but acknowledge

that to permit you sight of me

is condescension

beyond the ordinary.

(‘Francesco Albani’)

Elsewhere we are offered a monologue by the painter; a glimpse of the onlooker within the broader context of the gallery itself; a string of questions addressed to the painter, etc. These examples reveal Thomas’s restless urge for experimentation, and his interest in questions of aesthetics.

Other poems focus on domestic, personal subject matter. Their modest, anecdotal matter-of-factness, coupled with their recurring preoccupations about mortality and the passage of time, remind one favourably of Michael Laskey. These “domestic” poems contain some of Thomas’s most powerful writing, displaying clearly his twin capacity to be removed and involved, dispassionate and sensitive. There is, in Thomas, more than a little of T.S. Eliot’s “shred of platinum”, where the poet-mind is catalyst for chemical reactions, and “the man who suffers and the mind which creates” are successfully separated (‘Tradition and the Individual Talent’, 1919). Here are the final lines of ‘Froxfield Stop Off’:

Edward Thomas was here the year

my mother was born, writing about time,

not knowing how little remained. Today

I sold her flat while she continues to wonder

– does she? – whether to stay in it. Bit by bit

I am signing her away. I finish my tea, walk

across the car park, switch my phone back on.

The supple sentences of the opening prose poem fluidly shift focus back and forth:

The yarn of bright wool snaking across Great Aunt Edith’s bed where she was propped up knitting socks for me and dying for herself was like the road snaking through the Chilterns to Henley where duty would take us weekly to sit in her dim, tiny room heaped with the smell of sickness.

(‘Bright Yarn’)

In another prose poem, the highly original ‘Max Ament’, Thomas imagines the unlived life of a Holocaust victim. Here the invented biography of accomplishments is noteworthy, yet delivered with an obituary’s cool indifference:

The works for which he is best known are the Cello Concerto, the oratorio Ein Kind Unserer Zeit and in particular his opera sequence: Die Reise, Der Kommandant and Der Schwarze Hund.

Nevertheless, a mischievous, absurdist streak surfaces at times, even within material of great poignancy. In ‘Expedition’, a mother is caricatured as a polar explorer, yet the poem speaks movingly to a life’s hard-won achievements and the physical challenges of old age:

Several times a day my mother

sets out for the South Pole:

struggles layer by layer into outdoor gear

tugs at her snow boots, threads and tightens laces

comes blinking out of her tent

In ‘And these, Gentlemen,’, humans are analysed as specimens or artefacts by scientists or museum curators from outer space:

And these, Gentlemen,

are from planet ‘Earth’. Did you know

that they are mortal and aware of it?

That’s why, we think, they kill.

Elsewhere, linguistic experiment and frivolous word play are harnessed into satire, with targets as diverse as pigeons, railways, and gravity.

There are times when Thomas expects the reader to do some heavy lifting. Four poems about jazz draw upon the lives of particular musicians or the history of jazz. Even for casual jazz lovers, the result is more impressionistic – one derives a mood without always figuring out the exact context being described.

Overall, Momentary Turmoil shows Thomas to be a superb addition to a long line of Cinnamon poets going about their craft quietly and unostentatiously. He writes intelligent poetry that balances challenge, accessibility, and imaginative risk – not troubled by fads or fashions but busy doing a poet’s true work. His engagement with history, culture, and the history of culture broadens the material in this book to a degree that is, in a debut, both unusual and welcome.

Michael Loveday lives in Bath where he works as a creative writing tutor in Adult and Higher Education. He writes fiction, poetry, and prose poetry and is a book reviewer for Magma magazine. His flash fiction novella Three Men on the Edge was published by V. Press (2018), and his poetry pamphlet He Said / She Said by HappenStance Press (2011).

*****

Sarah Corbett’s A Perfect Mirror reviewed by Mike Farren

A Perfect Mirror by Sarah Corbett. £9.99. Liverpool University Press. ISBN: 978-1-78694-101-5.

In A Perfect Mirror, Sarah Corbett’s fifth collection, there is a deeply-rooted sense of belonging.

This most obviously relates to place, as many of the poems hold dialogue with locations in the Calder Valley, where Corbett lives, and the Lake District. However, these are both areas saturated in poetry, with the spirits of Sylvia Plath in the former and Dorothy Wordsworth in the latter. These two are to the fore of a number of poets and other writers explicitly or tacitly acknowledged in this collection, as Corbett also roots herself squarely within a literary tradition.

There is a run of Calderdale poems beginning with Swallow Hole, which faces Sylvia Plath’s House on the page. In the latter poem, Plath is not dead, perhaps not even mortal, but translated into the pagan genius of this place, where “It is always almost spring” – something those familiar with the Calder moors will recognise!

Such a mythologising impulse is applied liberally to the area, with the Sixteen Acres of Wicken Hill becoming “the earth” and Heptonstall Church an “alert wolf”. The intensity with which Corbett handles the immanence of place is one of this collection’s great strengths.

Another is the sheer variety and mastery of form, from the prose poetry of the three pieces entitled Praise Song to the delicate Rilkean sonnet The Unicorn and the gorgeous Sestina for Rain:

The dream flickers

and fails and morning steals the night, its hands

a lullaby on the sheets as the rain

flattens hayfields to a yellow hush

as hush go wind and rain at the window.”

Most moving of the three Praise Songs is the first, in praise of the junior doctor, who removed the placenta left after a stillbirth, sparing the narrator from further traumatic procedures:

He did this because he could, because in the lemon-walled room with the Peter Rabbit curtains at four in the morning there was just me and him and the small break the baby made in the fabric of things as it slipped away.

The second Praise Song is in memory of Jo Cox, M.P., and this introduces another aspect of A Perfect Mirror: the sense that the wider world is reflected in the local. This is set up strongly from the very first poem. Despite a disingenuous first line (for such an established poet) stating, “I am new to this” and an unpromising title, The Commute finds the world of global politics and the victims of war breaking into a simple train journey, with a child rescued from the rubble in Aleppo making geopolitics comprehensible on a personal level.

Nest, too, picks up this political thread, as the discovery of an abandoned nest at the moment of the announcement of the Brexit referendum result

…the news on the radio drops

us onto the path of history, as if we’ve

woken into a field at dawn – naked, wet,

the steam still rising.

I must confess that, without the volume’s notes I might not have identified which particular piece of news was meant, but with the benefit of that knowledge, this closing image nails the incredulity felt at the result and the sense of being lost in a new and dangerous reality.

However, by taking its title for the title of the volume, Corbett makes the poem A Perfect Mirror the heart of the collection. Incorporating phrases (including the title) from Dorothy Wordsworth’s Grasmere Journals, this six-part poem, extending over nine pages started life as part of a collaboration with artist Zoe Benbow for an exhibition at the Wordsworth Trust. As Corbett describes her experience of the place, Dorothy’s phrases phase in and out, like an old, badly-tuned radio. There is the sense that Corbett is attempting to invoke her, finding herself dreaming Coleridge’s dream of “a black-haired woman, wild-faced”, and leaping at the possibility that this might be a visitation from Dorothy.

There are fine evocations of the spirit and actuality of the place and powerful convergences between Corbett’s words and Dorothy’s (in italics):

we fit together, frame within frame

or overlap

a lacquered box

vivid with birds, trees, flowers

fragrant when we lift the lid

time, sister, colour – all colours

all melting into each other

However, I can’t escape the feeling that I am missing half of the picture – presumably the half that the artist’s work provided – and cannot quite get at the power this poem must have had in situ.

Nevertheless, A Perfect Mirror reflects brilliantly on the craft off its maker, on the places of its making and on the literary heroines and heroes with whom, it proves, Corbett is amply deserving to be ranked.

Mike Farren is a writer, editor, poet, copywriter and publisher based in Shipley, West Yorkshire. He writes news, features, profiles and reviews for a number of print and online publications, including Saltaire Review, Bradford Review, Bingley Review and The State of the Arts. His short stories have recently been published in Some Assembly Required. His debut poetry pamphlet, Pierrot and His Mother, was published by Templar Poetry in 2017.

*****

Michael Curtis’s Family Likeness reviewed by Derek Sellen

Family Likeness by Michael Curtis. £10.00. Cultured Llama Publishing. ISBN 978-1916412804

At a time when genealogy is an increasingly popular area of interest, Michael Curtis reminds us in ‘Family Likeness’ that, transcending data, poetry illuminates a family history more vividly than bare DNA results or website research. Curtis’s latest collection includes poems about past members of his family and about his own early life in Liverpool. In addition, the endnotes are effectively a brief memoir, with a nostalgic remembering of the significant objects of his own, and many other, vanished childhoods of the 50s and 60s: Dinky cars, Sturmey Archer cycle gears and a hinged wooden pencil box.

Any harvesting of the past however needs to temper nostalgia with clear-sightedness and significantly the opening poem is titled ‘Truth’. This fine poem lays out some of the collection’s preoccupations: that the ‘whole truth’ is something worth the search even though our knowledge is inevitably imperfect and that we are ‘in parenthesis’ between past and future generations. The poem seems to me to qualify all that follows by stating both the value and the limitations of the attempt to understand our place in family history:

all the stories we think we are

begin and end with a sentence

that put us in parenthesis.

The first section, ‘Familial’, releases all the anger and sorrow and pride that is latent in a family’s past, controlling it with tight, crisp verse. We learn about an honoured tradition of craft and industry; about his grandmother’s hatred of politicians after losing two brothers in the first World War, one to a particularly unlucky, inglorious accident; about his black-sheep uncle Oscar who encouraged him to drink and smoke as a teenager and earned his love; about his father’s service overseas in Burma after running away from home. The poems use census, roll of honour, family gravestone, frontline report, photo album as their sources. Family secrets are revealed and tragedies are narrated: wartime deaths, a treasured dog drowning in a pond, a secret sibling.

These are personal poems, often addressed to the relative they celebrate. They are intrinsically interesting as stories in their own right, engaging us with their dispassionate honesty, sometimes echoing our own experiences, but Curtis also subtly widens their reference, as in ‘Son’ about his father in Burma:

We fall from history

silk parasols

swinging unsteadily down

between tall areca palm trees

desperate not to snag.

The second section. ‘Twelve’, dealing with Curtis’s own childhood to the age of twelve, embodies that number in its structure: two dozen poems of twelve lines each, four stresses to a line. The paraphernalia of a fifties childhood are described memorably – the ‘brown leather falcon hood’ that covers a thumb sliced while carving, lead soldiers, ‘mud pies, skipping, hopscotch’, a ‘creak-brown satchel tugging / at its strap’. There is plenty here to excite the memory of anyone who lived through this time; even the do-it-yourself and gardening experts of early television are name-tagged.

At the same time, Liverpool as a city with its own civic ancestry is evoked, as the world of childhood widens. As this larger scene opens up, the strict formal jacket loosens in poem 24:

Raised on the brink of discovery.

arrivals, departures.

Tyres groan the floating dock,

Yellow Boat antics

spill beer-light across the restless river …

And the evocation of the whole city gathers power in the next section, ‘On Patrol’, as Curtis remembers his teenage years.

Curtis succeeds in evoking the core feelings of a child on the cusp of adulthood, nowhere more so than in ‘Don’t Know They’re Born’ that describes the sensations of being left alone in his father’s car. He explores

… the huge compass

of the steering wheel

the trio of dark pedals

and their unknowns, the car

and its potencies all mine.

His daydream of adult power is interrupted by the return of his father offering more crisps. Although the poems are rooted in a particular time, they encapsulate emotions that are common to all generations.

It is not an untroubled adolescence; in ‘A History of Violence’ for example, a confrontation with bullies ends like this:

When I twisted the key in the door

all I had left was an ember in my gut

that, despite a thousand better times,

was never quite to leave me.

Revenge for a mugging, memories of ‘repeated appeals / witness protection / nation’s condolence’, ‘the eastern steppes of Liverpool sixteen’ add to many other indications of the harsh side to life at that time and of the deteriorating city. In the far-reaching last poems of this section, ‘Making Water Flow Uphill’ and ‘Mirror’, a wider historical oversight emerges out of the personal. After celebrating the city’s past significance and delineating its decline as it becomes a victim of globalisation, Curtis ends optimistically:

On the river’s untouched air settle

thirty thousand voices

repeating hope in perfect harmony.

Liverpool has moved centre stage here, claiming its place in the writer’s story.

The final section moves into the present, titled ‘Here Now’. These are Kentish poems, reflecting Curtis’s own move to the south, and are meditative celebrations of countryside and city. He by no means paints an unalloyed idyll in a county where ‘somewhere across the channel, rumbles / of heavy howitzer threaten invading weather’.

As we reach the end of the book, it is as well to remember the lines in ‘Truth’ which establish the parenthetical situation of the individual:

… the truth that we’re a breath

between breaths, first to last, drawn

as the next one cries for air.

It is evidence of the richness of the collection that each poem demands attention rather than being merely a component part of its section. Words and ideas illuminate one another across the volume and the same discerning and exact consciousness is always at work. It is not a book to read quickly. The poems are rarely difficult or obscure but they require intellectual as well as emotional engagement.

In these four sections, we watch an individual seeking to understand and situate his own life, that of his family, and of his city. At the end of the poem ‘Circular’ about a trip past ‘cool orchestras of April bluebells’ and ‘profligate apple orchards’, Curtis advises: ‘Savour’. This is good advice also for the reader of ‘Family Likeness’.

Derek Sellen lives in Canterbury, Kent, and has written poetry, short stories and drama for many years. He has recently published The Other Guernica – poems inspired by Spanish art (Cultured Llama 2018). His poetry has been widely published in many places, including Cinnamon Press, Arts Council and PEN anthologies. His work has won awards in Poets Meet Politics, O Bheal Five Words, Poetry Pulse, the Wirral Festival and Poetry on the Lake competitions among others in recent years.

*****

Jessica Mookherjee’s Flood reviewed by Alison Jones

Flood by Jessica Mookherjee. £10. Cultured Llama. ISBN:978-0995738119

Flood by Jessica Mookherjee is a wonderful first full collection, the soaring waters of words working through sections entitled, ‘Churn’, ‘Flow’, ‘Break and ‘Surge’. There is power in water, and the characters that people this book have journeyed over it, through it, live beside it and marvel at it.

In ‘1967’ we stand with an immigrant bride, scarlet clad and strange to her newfound place, “Her sari billows in English winds”. The poem turns through the poignant parting of walking away, to the challenges of being from elsewhere “How quickly the shame sets in” the sense of being on the margins, moved through places on the energies of tides beyond control echoes throughout the collection.

In ‘Glass Sisters’ the speaker gazes at a statue of Kuan-Yin, a goddess who hears the cries of the world, which has travelled and been locked behind glass for decades, reflecting:

“We are all cabinet curios, waking occasionally, trapped behind glass, under small locks, tiny keys.”

Like children sneaking into a fairy-tale, we are invited to glance into spaces with voyeuristic eyes, to witness the pushing of boundaries and breaking through.

In ‘Hunger’ there’s “a wave of red silk in the breeze”, in ‘The Child’ the magnetism of the wild, as “she takes my big hairy hand, almost pulls me into the woods.” The voices in these poems are tricksters who shapeshift before our eyes, in ‘The Walkabout’ lichen grows between heart valves and the narrator is carried by a “bone-framed coat.” In ‘Wildlife’ a woman becomes an owl, a doe, and a fox before “she hid inside a woman’s flesh”. The storytelling in these poems is reminiscent of the magical and surreal worlds of writers such as Angela Carter, where the selves behind the narrative lyric I appear to be neither true nor false, simply assumed roles in surreal circumstances, doing as they must.

Mookherjee moves us quickly through the waters that churn to flow, and images of the natural world blossom through, in ‘Floriography,’ ‘Sweet Pea’ writes back to earlier experiences:

“Like Odysseus, we have all been seduced by the wrong drugs in our wine, slept with the wrong people, blown by winds in the wrong direction, and somehow found our way back home.”

The enjambed lines and careful use of end stopping separate home from the way travelled, and further emphasise the theme of being on the edges and not quite a part of something greater. Similarly, in ‘The Jezebel Spirit’ distance is created, with the admission ‘I’ve lost the spit of my loneliness and stuffed them into acorns and buried them’. The natural world once more provides cleansing for the angst ridden speaker, who when calmed in an earthy grave seeks to become ‘the exhale of a planet’.

As we journey through the flow, the motif of red clothing returns, In ‘Red’ the colour drips from windows ‘like blood’, from a bridal mark like a gunshot wound, blooms on the lips of a child trying on the mask of cosmetics, and in a skirt that “mesmerised me by the way it moved around my legs.” Red here is no longer the bridal sari, nor the flash of a red cloak in a deep dark wood. It becomes danger, a sign of “too much sun, too much beer, too much butter.” A sign of sorrow too perhaps, as “there’s blood in the bathroom again.”

Blood ties and ties that bind are a recurrent concern, with absent mothers returning in ‘Your Lost Mother’ so powerfully that “you can smell her crazy breasts in the numb light, taste her cold and disembodied milk.” The ancestors and ghosts of many take up residence, as in ‘Seder’ which addresses the holocaust, and what it might be to live through violence and atrocity and shapeshift into a new identity; as the taxi driver in the poem has had to do. When faced with a shocking truth of a dead family, all killed by the ravages of war, the speaker can’t help “Filling the flood of space with words I cannot bare”, yet the reply, rather than standing on ceremony and expected manners, is honest. Who cannot be moved by witnessing trauma, the characters in this poem at least are brave enough to admit this when asked the banal question, “are you ok now?”

In ‘Having my Sister for Dinner’ the notion of distance and trauma continues, with the speaker suggesting, “time folds us into origami boats, made by praying fools.” Maybe Mookherjee is suggesting that versions of the past and stories told across generations contain truths that may not be completely watertight. Yet, maybe in the scheme of things, this may not be as important as we think, with nature looming dominant again in ‘Naming Things,’ threatening to root the speaker down with the rhododendrons who whispers to her in a secret voice. Though the threat may be frightening, there is a pull of adrenaline too: ‘your hair will rustle in the wind, alive.”

Despite the draw of the wilderness, reality crashes back through the tides, in ‘Reunion’, where a shared history is voiced, then guilt kept away by distraction, one person rolling up, the other ‘writing everything down.’ Though with this comes disbelief, as in ‘Shell Shock’ there are questions, ‘are you sure you heard them right, your grandfather’s secrets?’

As the waters surge to flood proportions and draw the collection to a close, I was left wondering, whether Mookherjee’s words speak of something greater, the human desire to know where we are, and who we belong to, without the danger of our histories unravelling everything we know. In ‘Time Minus’ the man who holds the woman’s hand tells her:

“It is time to leave the past behind and trust in your own velocity. Love just does the work.”

The collection’s final and title poem submerges us in water, leaving us in “the surrounding flood”, which “sounds magnificent”. In a collection where girls are powerful as thunder and rocket fuel, I have to agree.

Alison Jones is a teacher, and writer with work published in a variety of places, from Proletarian Poetry and The Interpreter’s House, to The Green Parent Magazine and The Guardian. She has a particular interest in the role of nature in literature and is a champion of contemporary poetry in the secondary school classroom.

*****

Josephine Balmer’s Letting Go: Thirty Mourning Sonnets and Two Poems reviewed by Belinda Cooke

Letting Go: Thirty Mourning Sonnets and Two Poems by Josephine Balmer. £10. Agenda Editions. ISBN: 978-1-908527295

Jo Balmer’s trade mark is her highly individual mix of poetry, allusion and translation providing a powerful cross over between the academic and poetry scene. To see how she does this, take a look at her daunting research in Piecing Together the Fragments: Translating Classical Verse, Creating Contemporary Poetry (C.U.P 2013) which belies any suggestion that creative writing phds are less rigorous than straight literary research. Her poetry has consistently interwoven often difficult life experiences with points of high saga within key classical texts. The result is emotionally rich poetry embedded in an inclusive gateway into Greek and Latin literature appealing to specialists and general readers alike.

Now, in Letting Go we have thirty sonnets on the death of her mother which readers contemplating a similar loss will find seriously heartbreaking. Balmer’s sensuous concrete detail set against the actual seasonal cycle of the events — a common motif but one to which she gives a unique slant — takes us to the heart of what grief really feels like. It’s advisable, initially to read the poems as they stand before taking the second cultural journey beneath, assisted by Balmer’s helpfully inclusive source index, but when one combines all such readings it offers emotionally rich poetry which, offers a tribute to her mother’s life and their mutual bond — the small ways they looked out for each other shine off every page.

Straightaway, little details take us to the heart of the family loss. In ‘Things we leave behind’ an indelible stain on the family table ironically reinforces her mother’s absence: ‘In the centre, the faint circle of a wine glass/ abandoned to carry in warmed plates or dishes/…//indelible now, an everbleeding blemish’, all the more painful with the table now moved to a local café. From here, the final shocking leap: ‘I thought I’d see her / and then that week became forever’ makes plain this story will be about the grief of sudden unexpected death. ‘Ring’ is almost too painful to read, as Balmer unpeels the layers to reveal the subtle complexities of their shared lives. As her father holds his wife’s ring we see him: ‘peering through its opened circle as if a peephole into some new dimension, / where all the days and years might not have been’ . This nuanced reference to ‘dimension’ suggests a life paradoxically reduced and expanded: reflections on the past seemingly endless, while the future is both a vast unknown and a narrowing down and unpreparedness to live alone — a powerful poem showing controlled objective craftsmanship in the face of such personal loss.

Having hooked the reader in, her study of grief truly begins. She notes in ‘Suppliants’ :’Now we spoke only, / in laments, the savage language of hurt, /strangeness of mourning’ — ‘strangeness’ particularly apt to capture the absolute mystifcation of sudden death, that ’undiscover’d country… [that] puzzles the will’ as Hamlet puts it. And here Balmer’s use of classical allusion really takes such complex emotions to a new level. ‘To Do’ starts out seemingly straightforward on the practicalites of preparing for the funeral, but evolves into a more subtle meditation on what people ‘do’ with their shared lives alone and with others, here the mother daughter relationship, their shared priorities and loved memories. Without the source, the sonnet’s concluding sextet has suggestions of onsetting dementia, a daughter making to do lists to either humour or engage a mother who has lost her role as organiser. ‘Halcyon’, likewise seems to suggest dementia in the line: ‘searching for something to wear for someone / who was no one, who had already gone’ but with an unbearable concluding realisation of how far removed it is from the raw actuality of sudden death:

Looking back, what hurts more than the knowing

is the not knowing. That this was the calm

before the gales and the wild, storm-blown rain —

the halcyon days that would now be mine

forever, would always carry my name.

However, the source notes show that ‘Halcyon’ is inspired by the the story of Halcyone of Ovid’s Metamorphosis, who falsely assumes her husband is alive till he appears to her in a dream. The twin poems ‘To Do’ and ‘Halcyon’ now take on a very different but even more painful poignancy of life coming to a sudden, unexpected halt — the woman in To Do’ a totally alert woman who doesn’t know it is her last day, while In ‘Halcyon’ Balmer uses the source to describe her own feelings of shock and guilt when she discovers she had spent an enjoyable social evening unaware that her mother had already died. Ultimately, these two very different readings both feed into the common incomprehensibility of a loved one suddenly just not there.

Onwards from this raw realisation of sudden death, she works through the stages of grief which begins as – a club that you join: ‘…We used any weapon / to hand as the world split between those who / knew our pain and those who had it to come’ (‘New Meaning’) before going on to break down all that joining that club is going to mean.

The remainder of the book mixes more precious memories of the close mother daughter relationship combined with classical allusions of landscape, seasons or the underworld, all helping to fulfil the title’s remit of ‘letting go’. ’Glove’ is on the button on the way our mothers still protect us through into aduthood: ‘and feel once again, hers in mine reaching / out to hold me save, long past childhood, / on main roads or slippery paths,…’ . Descriptive extracts from classical texts match the collection’s chronology as well as providing ‘found’ metaphors for Balmer’s emotional states. Briefly in ‘Snow’: ‘The wind calms. Grief stilled’, while ‘Frost’ holds memories of: ‘warm hot baths / of her sheepskin still on its cupboard hook’. ‘Ice’ uses Livy’s account of Hannibal trapped in the Alps: ‘All winter the earth tipped from under us; /we were balancing on sheer precipice’, giving non Classics’ specialists a really memorable nice taster of how intimately Classics texts can connectwith contemporary ones, at the same time as we are made to feel dramatically shfting states of the ‘strangeness’ of grief.

The collection’s final few sonnets convey uplifting insights into ways of letting go: ‘Time will move on, flow in its own current. / What the dead leave for the living, their gift: / the pleasure in the moment. A life lived,’ (‘The Way Down’) while ‘Star’ offers a a pantheistic image of hope, in Petrarchan form setting up the loss of ‘parents, old friends and the house / we mourned as if a lover rashly left’ against acceptance of suffering as part of living:

…

Now the most beautiful of all the stars —

the evening star, sheperd star, Hesperus —

gathers all that light-tinged dawn has scattered;

it guides the fishing boats, herds in sailors

sends daughters running home to their mothers.

This is a collection that, beyond anything, is of value to those going through similar experiences, leaving them with insights which will convince them that here is someone who really understands.

*****

[1] A quote made by Fiona Cox in a discussion of the classical allusions in this collection: ‘Border Territories: poems from Letting Go: A Conversation between poet Josephine Balmer and classical scholars Fiona Cox and Elena Theordorakopoulos.

*****

Belinda Cooke completed a PhD on Robert Lowell’s interest in Osip Mandelstam in 1993. Her poetry, translation and reviews have been published widely in journals. Her books are: Resting Place (Flarestack Publishing, 2008); The Paths of the Beggarwoman: Selected Poems of Marina Tsvetaeva, Worple Press, 2008) and (with Richard McKane) Flags by Boris Poplavsky, Shearsman Press, 2009). She has also translated the Kazakh epic Kulager by Ilias Zhansugurov (Kazakh National Translation Agency, 2018). Forms of Exile: Selected Poems of Marina Tsvetaeva will be published by the High Window Press in 2019.

*****

Derek Sellen’s The Other Guernica reviewed by Fiona L. Bennett

The Other Guernica by Derek Sellen, published by Cultured Llama.

The Other Guernica is a rich and giddying tour inspired by Spanish Art and artists and the poet’s own encounter with the country and its culture. Acute in its observation, surreal in its imaginative leap of thought this is a project that rewards the reader with poems fired by provocation, storytelling and the sumptuous power of visual description. Taking another art form as the subject of a collection, perhaps especially visual art, is to raise the bar high on the poet’s craft to meet the power of the visual image with the written word.

Derek Sellen meets this challenge with a number of nimble feats; his balance of reverence with irreverence, his open engagement with the problematics of ‘gaze’ and through the fine detailed specificity of his observation – a still life comes to life in five exquisite lines: A hanging quince, gibbous. A green cabbage, its tender scalp folded in ribbed leaf. The cantaloupe’s opened heart of light. A gnarled cucumber curving beyond the frame. (Still Life – Still Life by Juan Sanchez Cotan) These grounding observational cornerstones act as poised counterweights to the curious obsessions, imaginary worlds and political commentary that the poet shares with us. Paintings become preludes to a story caught within the canvas, prompts to the painterly realisation of the poet’s own imaginings and secret windows onto the lives of the artists themselves.

The first room in the gallery, ‘Richer for its singularities’, offers an intense engagement with subjectivity and questions of the gaze. A layer of choices faces the poet – where is he standing, does he mimic the painter’s perspective or counter it, inhabit the imaginative realm of the subject or stand outside it and frame the context for us? Derek experiments with all these positions offering diversity of viewpoint and provocation alongside a celebration of the artists’ craft. In ‘Gitanos de Sacromonte 1908’ two painters’ works whose subjects are ‘gypsies, beggar women and female performers’, are considered within a dialogic form, its direct address challenging us alongside the artists, the subjects described as, ‘other than you and other than you want them to be’. This form of enquiry and debate is powerful within the poems and mostly accomplished with a deft use of structure and voice.

Occasionally the enormous scope of the mission topples the form and the lines reach for a layer of content beyond the space of the poem as in ‘La Tertulia’ where I was so engaged by the description of Angeles Santos’s painting of an all-female social gathering that the final lines of commentary detracted rather than enhanced my encounter. The poem, ‘It was the kind of hotel…’ opens up a new and different voice. This is the first poem where the painting is not in the title and the footnote references the artist’s work as ‘the inspiration for this poem’. The simplicity and haunting quality of the world that opens up here, a kind of imagistic fusion of Miro’s work and the poet’s own experience took me by surprise and remained for me one of the most powerful moments in the book.

As in a gallery where you go back to your favourite painting so I found myself returning to page 14. In the second section, ‘They Hardly Know Why – poems on war and violence’, Derek Sellen’s craft enables the reader to confront the shocking and inhumane depictions with both the full body blow of the images and the political fury that fuelled their creation. Often there is a daring and ingenious juxtaposition of our own reign or terror with that of the painting’s era as in the title poem, ‘The Other Guernica’ where the painter’s journey from specific images of horror to the ‘abstracted emblems for his time and ours’ illuminates the work of Luis Quitanilla and underscores its resonance for now.

Direct address, personification of subject and detailed description are all invoked to bring us into the poem often to be startled out of it into a consideration of our own consciousness. The third section, ‘The Circling Bee – poems on art and artists’, hums with a thrilling register that brings the experience of the paintings to life in extraordinary ways. Here the deft turn of phrase that is one of the hallmarks of this collection, ‘Phoebus tailgates Mercury’ in ‘The Sky of Salamanca’ and ‘plates and nations butt together’ in ‘Still Life’, lifts us out of mere viewpoint and into a visceral encounter with the world and the work that is at one and the same moment hallucinatory and grounded. The journey completes with poems of place and a sequence that maps a personal landscape. Here the canvas is the country, its history and the honesty and poignancy of one man’s encounter with it – a fitting coda to this rich collection.

Fiona L. Bennett is a writer, theatre practitioner and creative facilitator. She is founder and director of The Poetry Exchange and co-presents its podcast, silver award winner for ‘Most Original Podcast’ at this year’s British Podcast Awards. Her own work has been short-listed in The Bridport Poetry Prize and published in the USA and UK in a range of places including; The Northern Poetry Library’s Poem of the North, San Pedro River Review, River Lit Review, and BBC Radio 3’s The Verb. She is also co-director of The Map Consortium – one of the UK’s leading applied arts organisations.

*****

Michael Bartholomew-Biggs’s Poems in the Casereviewed by James Roderick Burns

Poems in the Case by Michael Bartholomew-Biggs. £10. Shoestring Press. ISBN: 978-1-912524-05-1.

In this very ambitious collection – or perhaps, more properly, constellation of collections – Michael Bartholomew-Biggs sets himself an enormously challenging task: to render vivid and distinct the voices of six students, two tutors, one guest reader and, from beyond the electronic grave, a departed wunderkind in a residential poetry workshop. (This leaves aside the connective tissue of fifteen narrative episodes in which both tutors are bumped off, with almost the whole cast potentially-having-dunnit.) In lesser hands, the book might have ended up as some kind of arch, genre-bending mash-up, a pastiche of traditional detective stories set “in country houses/in the thirties, blending/kedgeree with evidence” (‘Sincerest Form’), but instead is a triumph of inventiveness and wit, memorably sustained over the length of a short novel.

Take the work of George Hamblin, for instance. Along with Stephen Prince one of the two tutors hurtling towards their grisly deaths, and co-contender for a lucrative McMahon (“often pronounced ‘Mammon’”) Associates corporate residency, Hamblin is cast as the solemn, Larkin-esque figure, in contrast to Prince’s more youthful, edgy persona. In the first episode we are introduced to both through a sample of their work, and it would be easy to caricature Hamblin’s kind of staid ‘conservative’ verse. But in ‘National Trust’, Bartholomew-Biggs gives us instead a rather lovely study of introspection and age:

I’m out to mix with other, older English icons …

Turner, making permanent a moment’s movement, fixing it

in Petworth light, diffused as if by wind-snatched ashes

scattering across the sun

Nor –as the students settle in amongst introductory readings and chit-chat – are easy and less satisfying routes taken to distinguishing their voices. Stanley Spencer, possibly the nearest of the poets to the poet himself (striving in small, ingenious ways as principal detective to reconcile the wildness of codes to the precision of language), doesn’t speak much but sees a great deal. Devastated by his tutorial – and so equipped with the traditional, plausible motive for murder – he nonetheless rises above the arc of the story to find real and subtle meaning in detail, his work careful, softly-chiming, devastating in its insight:

Misprints make him restless still

by being not quite wrong. Is this

another tiny crease preceding

total folding of the world

as images from either side

fail to match but dip and slide

attaching half a floating face

to a poster on the wall?

(‘Grand Mal’)

Mary Maxwell, one of the older students and an actress by trade, would also be easy to create in a few strokes, perhaps gaily writing light verse or developing dramatic monologues; instead she delivers a sharp critique of insularity and social exclusion, charting the limited tolerance of one couple bringing the remaining half of another in line after a bereavement:

When Walt & Betty called

On Bert & Flo one Friday, Flo made sandwiches

And cups of tea. They talked about the weather

And the underpass; and when they left

Bert whispered as he shook Walt’s hand

I shouldn’t bother bringing her again.

(‘&’)

Only two words – weather, underpass – and all the rancour of soured familiarity pours forth. Even Seth Buckler, a guest reader brought in for professional variety (and perhaps to dispel the tension between the increasingly combative tutors), whose larger-than-life man of the people image (typical title, ‘Sewage & Money – Spot the Difference’) is more fleshed out than a cameo role would suggest. That sewage poem, for instance, performed no doubt as an entertainment, a provocation, winkles out a number of unpalatable truths from the shell of humour:

Vast amounts of both proceed through channels

out of sight

And unremarked upon until the flow

of either is disrupted.

So experts in the large-scale oversight of both

should be rewarded

For their heroic efforts at unblocking

either overdrafts or overflows.

But it is perhaps the almost-complete collection rounding out the book, a final unpublished work by the rising star Eric Jessop – who may or may not have been pushed to his death, and whose work may or not have been accidentally lost in an untidy publisher’s office, to be unearthed in an unlikely rescue from an abandoned computer – which shows us Bartholomew-Biggs’ true intent. Yes, the collection of voices is impressive – varied, real, each true to its own nature (no mean feat in itself), with surrounding text that brings the narrative elements alive in detective-story fashion, encoding layer after layer of possible solutions – with the whole cohering superbly, but ultimately it builds to the clues contained in Jessop’s own work. As perhaps do all poets, it speaks truth from the grave:

I’m treading …

toward the sandstone certainty of church

to huddle in a winter congregation

pinch-faced and jostling like penned cattle

(‘Feeling the Cold’)

AA solitary chorister …

is doing what his species is supposed to:

claiming and defending territory …

Blame diesel fumes, the neighbours’ cats,

the urban foxes if you like. The fact is this:

the only other feathers in this street are pigeons

(‘Dawn Solo’)

Both poems carry the flavour of the whole: precise, almost graven, moving at a superficially conversational pace towards the hardest and most lasting of truths – the endless capacity of human beings to invent mechanisms of distraction, to fend off knowledge of our own failure, the ever-widening damage of our species. A series of short poems, ‘Slow Turns of Events’, starts out in four-line riddles, but rapidly advances to the main theme, and in so doing, underscores the nature of book, detective genre and poetry itself:

A priest gets called a leveller

for stirring up his congregation

to insurgence. He ends up horizontal,

a shepherd trampled by his flock.

(‘Slow Turns of Events, 3’)

So both tutors, and many poets as well, Bartholomew-Biggs seems to suggest. Adapting Larkin, what will survive of us is not love, but work. How long that will survive is anybody’s guess.

James Roderick Burns was born in Stockton-on-Tees in 1972. He is the author of two short form poetry collections: The Salesman’s Shoes and Greetings from Luna Park (both from Modern English Tanka Press) – and managing editor of the UK journal Other Poetry. Under the Other Poetry Editions imprint, slated for a revival with a number of single author collections in 2013, he has also edited two anthologies: Still Standen and Miracle & Clockwork: The Best of Other Poetry Series Two.

*****

CHAPBOOKS

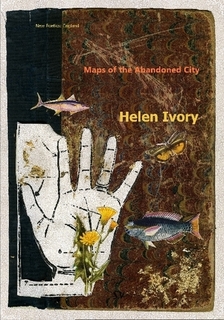

Helen Ivory’s Maps of the Abandoned City reviewed by William Bedford

Maps of the Abandoned City by Helen Ivory. £5.87. SurVision Books. ISBN: 978-1-912963-04-1

In May of this year, six years after Waiting for Bluebeard, Helen Ivory will be publishing The Anatomical Venus, her fifth full collection from Bloodaxe. It will rightly receive a great deal of attention, as this remarkable poet deepens and darkens her mythopoeic quest. But rather like Ted Hughes, the six-year wait has not been unproductive for the poet.

Apart from lecturing for the UEA/National Centre for Writing and editing her webzine Ink Sweat and Tears, Ivory has continued with her written and visual work in a series of chapbooks. Fool’s World, a collaborative Tarot with artist Tom de Freston (Gatehouse Press) won the 2016 Saboteur Best Collaborative Work award, and a book of collage / mixed media poems, Hear What the Moon Told Me (Knives Forks and Spoons Press) followed in 2017. Now her chapbook, Maps of the Abandoned City, with another of her own delicately surreal paintings as cover, comes from SurVision Books in Dublin with news of the abandoned city Ivory’s imagination inhabits.

The cartographer who maps the abandoned city is most likely the poet herself, each map being one of the poems. At the beginning of the story, ‘Long ago when the city was an infant/it lay on its back on a big white sheet’ (p.5) waiting until ‘The Cartographer stepped from a fold in the sky.’ Her first act of creation is to invent herself (p.6), but after that we are in a universe where material things come alive in a strange inverted form of Totemism.

The tunnel where the trains once ran ‘rolled the train track/back into its mouth and slept’ (p.11); mirrors ‘are hungry as hungry can be’ (p.12); ‘Dark comes home’ and ‘heaves off its boots by the fire’ (p.13); ‘rain in conversation/with a chair’ lies ‘belly-up in the park’ (p.16); ‘At noon, cutlery goes through the motions’ in ‘a mechanical dance of luncheon’ (p.19); ‘a staircase stopping to consider/if it is going up or down’ (p.27). Even traditional poetic images take on a life of their own, the moon imagining herself as ‘a sister in a hospital drama’ (p.21), the ‘imprint of a dusty angel’ in a cathedral watching ‘over the deserted pews’ (p.22).

Ivory’s epigraph – the Serbian proverb ‘Get your moustaches together, you’re going on a journey’ – certainly captures the imagination at work here, but there is something disturbing coming towards us from these poems. Families may arrange picnics, but while ‘Some have baked cakes,/others hold fish or babies as offerings’ (p.14), and lovers may fail to be in touch in life or death, as with the desperate Clairvoyants in the ‘Oui Ja’ (p.24):

Moreover, Alice needs to speak to Lawrence,

but there is nobody there

to take the call.

She frantically moves the glass to yes

yes yes and then, I do –

the door rattling against its jambs.

The disarming ‘Moreover’ is typical of Ivory’s often delightful humour, but a ghostly door waits behind the humour. ‘Dusk’ (p.26) is my own favourite in this characteristic Ivory mode:

At the amusement arcade

an out-of-date fortune teller

keeps pedalling her cards

inside her electric booth.

Nobody thought to unplug her

so the future is pushed forward

on lavender cards

with a fleur-de-lis motif.

A stranger will call with tidings from afar.

Beware the season’s turn!

One of the light bulbs is out

casting her left side in shadow.

In the final poem, ‘The Cartographer Unmakes’ (p.30), ‘It’s snow that gives her the idea,/bleaching parks of desire lines/and blotting out coffin paths’, the maker unmaking her world:

And when there is no one left

to remember the City,

when all has turned to fireside yarns and myth,

a traveller will open out

some spotless pages of the map

and imagine lady fortune shines on him.

William Bedford’s poetry has appeared Agenda, The Dark Horse, The Frogmore Papers, Encounter, The John Clare Society Journal, London Magazine, The New Statesman, Poetry Review, Poetry Salzburg Review, The Tablet, Temenos, The Warwick Review, The Washington Times and many others. Red Squirrel Press published The Fen Dancing in March 2014 and The Bread Horse in October 2015. He won first prize in the 2014 London Magazine International Poetry Competition. Dempsey & Windle are publishing Chagall’s Circus in April 2019.

*****

Peter Raynard’s The Combination reviewed by Emma Lee

The Combination by Peter Raynard. £6. Culture Matters. ISBN 978-1912710041

Subtitled A Poetic Coupling of the Communist Manifesto, The Combination is a long poem to mark the 200th anniversary of Marx’s birth and the 170th anniversary of the publication of the Communist Manifesto. The poem is presented as a call and response with a line from the manifesto and a contemporary reaction (in italics):

All are instruments of labour, more or less expensive to use, according to their age and sex

worker bees pollenating the pockets of private development, watch our sting

No sooner is the exploitation of the labourer by the manufacturer, so far, at an end, that he receives his wages in cash

with no questions asked, the rich have enough to pay all of the tax.

that he is set upon by the other portions of the bourgeoisie, the landlord, the shopkeeper, the pawnbroker, etc.

from one hand to another, empty palms to clenched fists, we gather them to raise them

The lower strata of the middle class – the small tradespeople, shopkeepers and retired tradesmen generally, the handicraftsmen and peasants,

a lumpen lot with ragged trousers, who can no longer afford a belt

all these sink gradually into the proletariat, partly because their diminutive capital does not suffice for the scale on which Modern Industry is carried on,

money once floated around, like fish caught and put back in the pond

and is swamped in the competition with the large capitalists,

whose nets have squares as small as an eye that cannot see.’

The format gives it a subversive feel, however, the response does not undermine the points made in the original. It underlines the relevance of Marx and brings it up to date. The line, ‘money once floated around, like fish caught and put back in the pond’ suggests the circulation of money tainted it – a caught fish is rarely completely unscathed – as if the proletariat shouldn’t touch money because they make it unclean. The ‘ragged trousers’ could be read as a reference to The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists by Robert Tressell (Robert Noonan’s pseudonym.) Later, attitudes to women receive a timely update:

For the rest, nothing is more ridiculous that the virtuous indignation of our bourgeois at the community of women

from death at the Epsom Derby, to Greenham Common, to #metoo

which they pretend, is to be openly and officially established by the Communists

I hereby declare the Prior Lives of the Rich Museum open, please mishandle the exhibits as you wish

The Communists have no need to introduce community of women: it has existed almost from time immemorial

hear the words of Calliope, the open scroll of Clio, beloved Erato, the music of Euterpe, dance with Melpomene & Terpsichore, meditate with Polyhymnia, laugh with Thalia, look at the stars with Urania, and one for luck, the poetry of Sappho

Our bourgeois, not content with having wives and daughters of their proletarians at the disposal

Rita, with Lord Robert, and Sue too’

It sweeps in the suffrage movement, campaigns against nuclear weapons at British airbases, #metoo and looks to the Muses, not as passive sources of inspiration but as active writers, musicians, dancers, astronomers and thinkers. Peter Raynard reminds readers that working class and poor women have always worked, it was bourgeois women who were trapped by being their husbands’ property and trained by society to think work beneath them. This enabled some men to divide women into those who were untainted by work and worthy of protection and those who could be exploited because their precarious position and fears of poverty could be used against them. In the final section, the manifesto is further updated with contemporary references to popular TV presenters Ant and Dec and a quote from Arundhati Roy:

‘Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communist revolution

Let’s get ready to rumble, watch us wreck the mike, watch us wreck the mike, watch us wreak the mike, psyche! (Ant &Dec)

The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains

& hi-vis jackets, tabards, uniforms, see through knickers & a peep-hole bra, plus endless hours away from those near & dear

They have a world to win

‘Another world is not only possible, she is on her way, and if you listen carefully, you can hear her breathing’ (Arundhati Roy)

Arundhati Roy’s quote is astutely chosen, it brings images of Mother Nature or earth as mother.

In The Combination’, Peter Raynard has created a timely labour of love, a means to revive interested in Marx’s theories to a new generation through use of wry humour, a subversive attitude and an impressive range of references. Its wryness prevents it becoming a dull-but-worthy style exercise but instead a poignant view of history, dashed with irony and a clear working class perspective.

Emma Lee’s most recent collection is Ghosts in the Desert (IDP, UK 2015), she co-edited Over Land, Over Sea: poems for those seeking refuge, (Five Leaves, UK, 2015), reviews for The Blue Nib, The High Window, The Journal, London Grip and Sabotage Reviews. She blogs at http://emmalee1.wordpress.com.

*****