*****

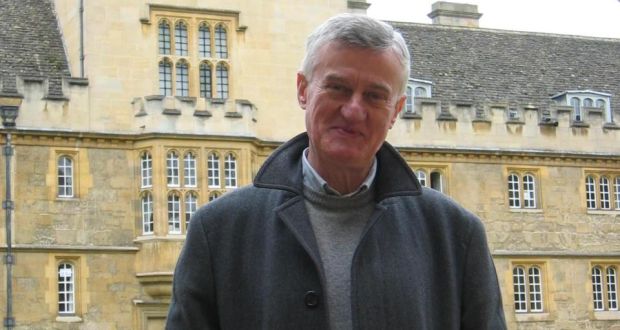

Bernard O’Donoghue was born in North Cork in 1945. He moved to Manchester in the United Kingdom aged sixteen and has lived in the English city of Oxford since the age of twenty. He has spent all his adult life working as an academic of English literature, specialising in medieval English. His latest collection, Anchorage, follows on from six earlier collections, all of which have been highly praised, and several volumes of translation.

He was awarded the Whitbread (now known as the Costa) Prize for poetry and in 2008 Faber published his Selected Poems. Despite having spent most of his life abroad, O’Donoghue still speaks with an Irish accent, and his Irish accent also informs his personal poetic idiom. Undoubtedly his frequent revisiting of the setting of his childhood has reinforced his essential Irishness.

The Irish poet Brendan Kennelly once said that ‘O’Donoghue’s poetic world is one where stories are more important than ideas.’ O’Donoghue agreed: ‘He’s right. He’s always right. You’d like to think that some idea comes out of the story – but the story is always primary.’

*****

*****

The Anchorage by Bernard O’Donoghue. £12.99. Faber & Faber. ISBN: 9780571387939. Reviewed by William Bedford

For a poet who is also a scholar of medieval literature, something permanent may be made out of the ordinary experiences of life, especially given a religious dimension which is so lightly worn. O’Donoghue’s title immediately alerts us to such deeper meanings: not only the coastal waters suitable for a ship to anchor in, or garden plants that need good soil for firm anchorage, but in the medieval anchorhold where an anchorite might live.

Lewis’s The Allegory of Love tells us how that can be done, grounding the mystical in the real, but a lifetime’s wisdom is also here in the epigraph to ‘Broken Dreams,’ quoted in the original Latin from Dante’s Paradiso, but in translation including the perhaps self-reflective “though nothing more returns to mind,/so I am now” (1). We can obviously read allegory into anything, but it is no surprise to find it in the work of a poet and teacher who has lived his life with Piers Plowman and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

The influence is there in the first line of ‘While the Sun Shines,’ – “In the meadows of the dead they’re hard at work,” – reminding us of Piers Plowman’s “A fair feeld ful of folk fond I ther bitwene”, while going on to claim the scene for the poet himself with “Some I recall the names of, but can’t remember/Which of them the name attaches to.” ‘Time to Go’ has the poet finding himself in the wrong hotel room, asking a stranger “Isn’t this my room?” only to be told “I don’t know. I guess when you’ve settled up/down at the desk, then you’ll be free to go,” the enjambment “up/down” imitating his confusion. The final poem in the collection, ‘Winding Up,’ has a performer alone when his audience have left, “free to pack up and make for home”.

Moving closer to the moments in life which seem epiphanies, the eponymous ‘The Anchorage’ has ‘the invisible/Last leaping’ of a farm’s dog symbolising both a community’s shared response to a catastrophic fire and a family’s personal loss of a favourite companion. ‘Pruning in August’ has the poet-gardener trimming “off all the shoots/that might have flowered later in the year” before “departing/at summer’s end”, until “we can’t bear to think/of their display before the next comers/as if they’d never been the heart of things for us”. And in perhaps a gardener’s way of thinking about life in ‘Calendar Customs,’ deciding not to keep a record of all his plantings, but chosen:

to let them all take their chance

and maybe create the circumstances

when someone, fifty years from now, will come

upon a berberis, rose or lily

in some unlikely place, just as I found,

fifty years ago, a strawberry plant

where you’d least expect it, in the ragged

back half-acre behind the old screen.

The epiphanies of course grow from the imaginative journeys the poet is making. In ‘Pre-check-in’ “It’s always the same dream before you travel:/Cases not packed, unsorted contents/Thrown on the bed” until you arrive and realise you “could have spent those last few hours at home.” ‘Folk Tale’ begins with “I wish I’d never started on this story” and ends glad “To turn at last into our own front yard”. With the consolatory ‘Safe Houses’ Kate retreats in her nineties to her eponymous safety, “And there she was, with twenty others,/all chattering and laughing like a parliament/of magpies, not to each other/but to the unhearing world outside.” I enjoyed O’Donoghue’s quiet nod to medieval literature with his “parliament/of magpies”.

The Catholicism of the life is most living in unspoken moments. In ‘Rule-Breakers’ a Lenten memory of broken vows, eating chocolate “having held out/for thirty days”, “tasted not of ash, but of something worse:/the sweet poison of a chosen vow broken.” More elliptically, in ‘Madonna’ the poet remembers a young woman “crying, impatient/To be alone, your copper hair pulled back/By the wind as you urgently waved me off/With that still-loved, still-unrecaptured hand”, reminding him of “a seventeenth-century virgin at the heart/Of the picture.” Even myths such as the ”blue mountain hare” that “earlier dwellers” had seen in ‘Lepus’ have their mystical experience to share, whilst the pilgrimages in ‘Back on the Island’ will remind Catholics of Station Island, with its final reflection:

When things are lost,

we keep on looking in places where we know

they are not because we’ve looked there already.

But they remain the most likely places:

back on the island, we’ll look there again.

Two poems especially remind me of the rituals of death in a community where you are known. ‘Jim Cronin Recalls his Parting from Denis Hickey’ shows us the courtesies of a friend’s dying, “always walking on without a word to the end/of the path”, until “I thought again/of all these minor differences/three days later at the memorial Mass,/and when we lowered his coffin into the earth.” ‘Homesickness’ is equally sensitive in its quiet drama of devastating grief, the mother in the poem so ill “she couldn’t face the chapel the cold day/of her favourite daughter’s funeral”, but remained at home, avoiding any sight of the passing hearse.

The bells tolled through the midday sleet.

The minder pictured the mourners by the grave:

the coffin lowered, the tears of the relations.

But still Mamie nodded at the fire,

Well beyond the reach of grief.

Bernard O’Donoghue has long explored the theme of exile, in a sense the familiar experience of a people with a history of political oppression, but in The Anchorage, he returns to his own origins. Here we have poems full of the minutiae of country life: school and neighbours, telephones before we all had them, haycocks left to dry before adding to a haystack, pulsators for milking machines, farmers walking the land to check the boundaries, the coffin maker working “to leave the world better than he found it.” Bringing Chesterton’s ‘the wonderful and wonder’ together, The Anchorage offers us some of the most moving and imaginative poems this fine poet has written.

[1] Robin Kirkpatrick, The Divine Comedy (Penguin Classics, 2012) 33, 58-63.

William Bedford is a novelist and poet whose work has been published in the Jesuit review America, The Catholic Herald, Catholic Gazette, Catholic Life, Catholic Weekly, The Furrow, Intercom, Prairie Messenger, The Southern Cross, The Tablet and in secular publications such as The Daily Telegraph, Encounter, The Independent Magazine, London Magazine, London Review of Books, The Nation (New York), Temenos, Tribune, The Washington Times and many more.

*****

Here nor There: Bernard O’Donoghue interviewed by William Bedford

(Previously published in Agenda (May-June 2013)

‘In the real world, of course, there’s no such person

as a Bona-Fide traveller. They will pull

the glass out of your hand and order you

to go back to the place you came from,

whatever you might have called that at the start.’

‘Bona-Fide Travellers’ by Bernard O’Donoghue

*

William Bedford: The idea of exile – or at least leaving home – is there from the start in your work. I’m thinking of a poem such as ‘A Nun Takes the Veil’ which you chose to open your first full collection The Weakness and eventually your Selected Poems. Could you take us ‘back to the place’ you yourself came from?

Bernard O’Donoghue: Well, I grew up in the north of County Cork, near a village called Cullen and a town called Millstreet. My father was a farmer there in the townland of Knockduff – at least he inherited the family farm there, but he hated farming. He worked as a travelling insurance salesman for the Sun Life of Canada, which meant he drove to picturesque places all over County Kerry mostly. In the summer we often travelled with him, for the trip. But he hated the selling too: he was the most unlikely salesman ever. My mother came from Manchester, from an Irish background. She did a History degree at Manchester University in a great era – people like Lewis Namier and A.J.P.Taylor taught her there. But she was an excellent farmer and did all the work around the place. Despite the Irish background and her principled fondness for Ireland and everything to do with it, she always seemed English, which made for a slight exoticism and anxiety about our place in the community – my two elder sisters and me. It was on the whole a very happy set-up I think. We went to Manchester for holidays, which was also exotic. We were Man City fans: my mother had been an enthusiastic attender at City and at Old Trafford for cricket in her youth; her father George McNulty sang in the Hallé choir – in fact they were pretty strange Manchester-Irish altogether. Her mother was Margaret Sheahan from Nohoval near Rathmore, four miles away from us. She went in for a kind of middle-class, aspirational style too – though she said she never felt at ease out of Ireland. I always think of her when I read Louis MacNeice saying ‘I wish one could either live in Ireland or feel oneself in England.’

William Bedford: I think you left County Cork when you were sixteen? That’s often an awkward age for most of us. Do you remember your feelings at leaving Ireland? And indeed arriving in England?

Bernard O’Donoghue: My father died suddenly at a football match in Cork (I was with him) in March 1962 when I was sixteen, yes. It was a huge shock of course: I remember a curious consequence of it – or I suppose it was that. I have never felt entirely at ease in the company of one other man since then: I feel more comfortable and safe with women (allowing for the other kinds of gender unease that arise there of course). I had already moved from the countryside to a school in Cork City that year, so in some ways that shift was a preparation for the move to Manchester. Idyllic as the country upbringing had been – and it really was in many ways: saving the hay, growing fond of the animals and so on – I loved both cities, Cork and Manchester. Leaving Ireland was strange, but we never wholly did: I have never not spent at least eight weeks in Ireland every year. And I loved Manchester (I still do): the bookshops and the sport – going to Maine Road, playing tennis in For Lane Park and so on. But above all the music: for the next ten years I was obsessed with classical music. I am not sure why: I think I saw it as the most certain route to self-improvement! I know nothing about the mechanics of music though: I still can’t read music! But the experience that I thought I found most fulfilling was the Hallé at the Free Trade Hall, and chamber concerts and opera. I went every Saturday morning to Gibbs’ second-hand record shop in Lower Moseley Street: it was Heaven. And of course the music scene there was quite a big deal: I saw the Oistrakhs and Rubinstein and Tortelier and Arrau – and of course Barbirolli all the time.

William Bedford: I remember you quoting Heaney saying ‘strangers are people other than natives of County Derry’. Do you have any similar feelings, even after all these years, about County Cork?

Bernard O’Donoghue: I think I was paraphrasing Heaney’s profound poem ‘Broagh’, about language and locality. I don’t think I do feel like that about County Cork – though it is without question the place I love most and feel most at home in. But there are other places I am strongly attached to too: Manchester, as I have said, but by now of course Oxford where I have lived most of my life: forty-six years to be precise. My children have grown up here and they all live in the South-East of England. My wife (who is the classic ‘more Irish than the Irish themselves’ for which I am very grateful) is from the North-East of England. I discovered that area when I met Heather, and I was completely blown away by it: those wonderful shorelines and wild inland country around Teesside and Northumbria and North Yorkshire. The football results have three focuses of anxiety: Man City, Middlesbrough and Oxford United (where my son Tom is a season ticket-holder).

William Bedford: When did you begin writing? Was this just something you did naturally, an accepted part of your home and school life in Ireland, or a response to the changes when you moved to England?

Bernard O’Donoghue: No, I didn’t do it naturally, or early. I was always keen on reading, especially Dickens and comic writing – like Lewis Carroll and Three Men in A Boat. But everything. When I moved to Cork City, the idea was that I would do Engineering at University College Cork. But I had an inspirational teacher of English and Irish at that school, Presentation College, Dan Donovan who is a great actor and theatre director (still flourishing in his nineties). His declamation of Macbeth won me over to English particularly. I remember one summer evening in 1962, reading ‘The Ancient Mariner’ in the flat I shared with my sisters on Donovan’s Road: reading Orwell and Lawrence there as well. Then, when I moved to England and ‘The Two Cultures’, I had to choose one side or the other for A level, the Maths side (called ‘the Moderns’) or the literary side (called ‘the Lits’). This was at the grammar school, St Bede’s where my grandfather went a hundred years back (I was very lucky they took me in there: why did they?). So I abandoned Maths with some reluctance. I was pretty good at it – at least I was very numerate, though I suspect I was conceptually pretty limited. I had another dabble with the positivist world when I worked with IBM for a year in 1968-9. I loved the people who worked in IBM, but I was useless at the work. But in my big reading days, I never aspired to write: it was a kind of dream, if that. Writing was an august thing that other people did: wonderful but out of my reach, except as a consumer. Like Music I suppose.

William Bedford: You went up to Lincoln College, Oxford, in 1965, and in a way, if we are going to be talking about forms of exile, this is a deepening of the ‘differences’, to pick up on one of the theorists’ favourite words. You would have travelled not just from Irish English to English English, but in studying Old English and Middle English, gone back to the roots and the culture of the language. That was obviously the structure of the Oxford English degree, but can I ask you about the impact that literature had on you? I think you described ‘The Seafarer’ and ‘The Wanderer’ as your ‘model for the perfectly formed lyric poem’?

Bernard O’Donoghue: Yes, that is right. Heaney said getting a letter from the poetry editor of Faber was like hearing from God Almighty; I have to confess that my equivalent moment was the letter from the Senior Tutor at Lincoln, offering me a ‘place to read English’, on my birthday in 1964. It really was a kind of invitation to Heaven on earth. I loved medieval English (Chaucer especially), but in fact I did the general English course from Beowulf to 1900. If I had a specialising interest at that point it was Irish writing in English, rather than the medieval things: Yeats and Joyce and the Cork short story writers – especially Frank O’Connor. (I still think he deserves as high a place in world literature as Yeats and Joyce and Beckett and Heaney.) I enjoyed the English course immensely, but it didn’t entirely match my enthusiasms – except maybe Chaucer and Shakespeare and Wordsworth and Dickens. Joyce was too modern for the course (Yeats got in because he had published ‘a substantial body of work’ by 1900). My friend and contemporary, Steven Rose, a brilliant son of Polish-Lithuanian refugees (his family history was horrifying though not much dwelt on: as a background it gave us all some sense of seriousness maybe), gave me both Swann’s Way and Ulysses. There was a lot of heavy-duty reading outside the Oxford course, as well as in it of course; and – getting back to your question – there was a lot of ‘other’ in all that. I began loving the Anglo-Saxon elegies so much when I started teaching them in 1971. I have loved teaching Old English all my working life – though I never felt I had the total grasp of it that the real pros had. I still think that ‘The Wanderer’ and the others are my perfect model, mainly I think because of the way they balance a purported physical, sensory experience with a serious moral conclusion. They are consolations, both generically and in practice. They are also very brilliant in language and imagery of course – and mysterious. A good poem must always hold something in reserve. And it must, ultimately, be serious I think! That is what I admire so much about those poems.

William Bedford: I don’t know whether I’m inventing a question here, but I’m wondering whether there was anything of C.S. Lewis’s experience in your own experience. You remember what he wrote in Surprised by Joy about the Norse sagas and his own sense of ‘northernness’, something in that literature which called to something deep within himself. Obviously, if the call was really deep you might not even be aware of it, but were you conscious of anything like that?

Bernard O’Donoghue: That is very interesting. Lewis was Northern Irish Protestant, and very religious of course: I grew up as a very religious-observant Southern Irish Catholic, but I think in a less profound way (I am not as profound a thinker as Lewis). But there are affinities I think: I am sure the reason I took to the medieval academic world was that I half-knew it already, from the Catholic upbringing. You were familiar with doctrines like the Immaculate Conception and the Real Presence and the Infallibility of the Pope at the age of eight, so the apologetics that medievalism entailed was not such a big deal. More interestingly maybe, you encountered words like ‘vouchsafe’, ‘intercession’ and ‘supplications’ younger even than that, without any sense of what they meant. It was like learning a foreign language unsystematically – and at the same time I was learning Irish at school from the age of five. Both the philology and the uncomprehended language were coded in you from the start. So I did a two-year postgraduate degree in the Middle English period (1100-1500), and I took papers in Medieval Philosophy and in Dante. I nearly failed the B.Phil. because I did Dante without knowing Italian (testing to the utmost T.S.Eliot’s theory that you can read Dante without a proper knowledge of Italian). I also never got the hang of Philosophy – Aquinas, Scotus and Ockham. Scotus was full of suggestive phrases – the things Hopkins liked (haecceitas and all that) – but my brain certainly wasn’t strong enough to hold his sophistical arguments in an ordered sequence. De Primo Principio is the hardest book in the world. But I think, as I say, I was programmed to think that not understanding things did not matter: that there is even a suggestive miasma around the uncomprehended! Anyway, what took me into that suggestive nightmare was the dim half-grasp I had from serving Mass and gabbling Latin. ‘Sursum corda.’:‘Habemus ad Dominum’. I loved William of Ockham’s logic though; it anticipated some of what goes on in French modern literary theory. He would be my nomination for the greatest Englishman, in response to that survey a few years ago. Ahead of Shakespeare and Churchill: even of Bruce Forsyth.

William Bedford: You completed your undergraduate and postgraduate studies in 1971, and ‘after this, you might say, nothing else really happened’. You settled in Oxford with a lectureship at Magdalen College (1971-1995) and fellowship at Wadham College (1995-2011), and a career of teaching and writing. But Carpenter’s point, of course, in talking of Tolkien, is that the ordinary life may not be the best guide to the secret life of the poems. You published three pamphlet collections before The Weakness. We’ve detailed these in the bibliography, but can you tell us something about the circumstances of those collections?

Bernard O’Donoghue: It all started with John Fuller who was my modern colleague at Magdalen College. I was extremely fortunate – again – to be given a lectureship in Medieval English there by Emrys Jones and John Fuller in 1971, straight after I had scraped through the B.Phil. John, who was already an acclaimed young poet, ran the college poetry society, the John Florio. You had to submit a poem anonymously to go to the meetings, so I did. It was the only way of meeting the students in a social and bibulous way, and it was great fun. John has a genius for encouraging and developing writers: he criticised the submitted poems with the same Empsonian rigour that he applied to everything in the English canon. Even more remarkable, he published the members’ work – often fairly basic stuff – in small, beautifully bound pamphlets, on his Sycamore Press, on an ancient, oily machine in his garage. I have never encountered such wholly disinterested generosity anywhere else. Many people started in that way with John: James Fenton, David Harsent, Alan Hollinghurst, Mick Imlah…. So my first publication was a beautiful green pamphlet called Razorblades and Pencils, published by John in 1982 (when I was thirty-six: I was far from a precocious beginner). The second pamphlet, if that is the correct term, was The Absent Signifier in 1990, a beautiful, large, pale blue booklet, published by Peter Scupham at his Mandeville Press. This was another generous and disinterested enterprise, and again it was a huge boost. The other pre-Weakness book was of a different order though: Poaching Rights, published in Ireland by Peter Fallon at Gallery Press in 1987. This was my first full-scale slim volume: a really beautifully made book – dark red, and in hardback and paperback. That was a great breakthrough and I have an enduring attachment to it. I am deeply grateful to Peter Fallon who was a marvellous, alert editor.

William Bedford: How do you approach the writing of each poem? What is the writing process like for you?

Bernard O’Donoghue: It varies, doesn’t it! Very occasionally the thing falls into place and it hardly requires any adjustment. Sometimes something gets requisitioned which is a great help. I tend to have scraps hanging around unmodified for years; mostly they don’t come to anything, but just occasionally something sparks them back into life. That is the exception rather than the rule though. I sometimes think that I have boxed myself in to an extent that makes it almost impossible for me to write anything. Mostly I don’t write in rhyme because I have this idea that the form somehow becomes the objective and can get in the way of the ‘message’ (though I know this is not true of – e.g. – Yeats or Larkin!). Then I suspect poems that are all message: poems that have a design on us, as Keats said, so that is another possibility closed off. I don’t write comic poems: I don’t like ‘light verse’, even when other people write it. I am afraid of all the things it is right to be afraid of: self-righteousness, preaching, humour. So what is left? What do I write about? I like David Constantine’s notion of ‘poems that matter’. But by the time I have finished setting up the constraints, there isn’t much left to matter. I keep hearing myself saying to fretful writers ‘you can’t write too little’; but I think I may have overdone that principle. I don’t write fiction: for whatever reason, I can’t. But on the odd occasions when I have tried, I go through the same process. I hate surrealism: again, not serious enough. (Actually, I do like comic fiction though.) But then I don’t like the obsessive current school of novel-writing that says you have to research all the details to make sure it is getting things right: what is the point of writing in fiction at all then? So there isn’t much of a gap between those two positions. Medieval fictions are the best: Troilus and Criseyde or Gawain and the Green Knight. And Piers Plowman is nice and serious.

William Bedford: Is a critically sophisticated self-consciousness a problem for a writer? I’m thinking about the difference between Coleridge’s synthetic and analytical imagination, the difference between writing and teaching poetry?

Bernard O’Donoghue: I think one of the things that excites you into writing is reading and wanting to – in a pale way – do likewise. I agree with what has become a bit of a mantra with creative writing teachers: if you want to write, you must read. I think my previous answer deals with this in a way, doesn’t it. But I find I don’t apply the same critical faculties to my own writing at all. I think maybe that is the problem with poetry like Empson’s (he is my favourite critic): it is like writing in a mirror so that the critical evaluation comes first. I think maybe the real answer is I don’t know, because I don’t teach poetry much in that prac-crit, Empsonian way, much as I admire it. The kind of poetry I teach, or at least the way I teach it, tends to have a historical bias: ‘Yeats in his context’ or ‘Chaucer in his time’, kind of thing. I am no good at workshops for this reason, and I always say no to them now: the only thing I can find to say is ‘That looks fine to me. I mean, do you want to write poetry?’ I briefly coached a very good rowing eight and I had exactly the same feeling. I love the social side of teaching – its friendliness. But I am a hopeless teacher as far as telling people things they don’t know goes, or pointing them in some other direction. Recently I have felt I am starting to get the idea – but sadly I have just retired.

William Bedford: In Heaney and the Language of Poetry you made a comment about the significance of form for Irish poets since the end of the nineteenth century: ‘a consciousness of Irish poetic forms has been unignorable since the end of the last century for all Irish poets writing in English’. How important are such forms in your own practice?

Bernard O’Donoghue: Not very important: indeed I don’t think that what I said there about forms is true. I am hoping to update that book to take account of Heaney’s magnificent later work and the bearing of language on it; but if I do I will have to change some of those early propositions. Certainly, it is nonsense to say that those forms are ‘unignorable’ for ‘all Irish poets writing in English’. Sorry, everybody! On the other hand, there has to be some affinity between the writer’s writing and their speaking voice and accent, at least in the kind of colloquial-tending poetic language I write in. That may be the real answer to your question about the ‘writing process’ above. Maybe that is the one way out I allow myself.

William Bedford: You published four full-length volumes between 1991 and 2003. Even allowing for the fact that several of the poems in The Weakness had already been published in pamphlet collections, this is a remarkable achievement. Shelley’s ‘inconstant wind’ blows when it will, I know, but are you aware of any particular reason for this sudden increase in productivity?

Bernard O’Donoghue: Well, The Weakness in 1991 was a bit of a cheat because it drew on some poems that had been in Poaching Rights which I felt was an equally ‘whole’ book. The next three were fairly short I suppose; I always felt they were just reaching their target in size. I had a series of excellent but fairly permissive editors at Chatto who left things as I gave them. (Not that they weren’t helpful: Rebecca Carter for instance took a strong line against the first title I proposed for Outliving – it was such a bad title that I can’t bear to repeat it here! She was a terrific editor.) I don’t think there was anything in my circumstances that made me write. 1995 was my fiftieth year and it was a bit of an annus mirabilis. It was the year I started at Wadham, it was a glorious summer when I cycled around Sligo during my first Yeats summer school there, and Gunpowder won the Whitbread Prize. The next two books came at four-year intervals. I liked the titles of both of them, and of course all those Chatto books had wonderful covers. Then there was a bit of a gap after 2003, interrupted by the Selected Poems in 2008.

William Bedford: The Weakness came out in 1991, and in a comment Tom Paulin talked of your gift for ‘displacing our more predictable reactions to things as they are so that we glimpse their underlying tragedy’. The storyteller’s narrative skill is apparent from the start. Is that a natural facility inherited from rural life and Irish literary traditions?

Bernard O’Donoghue: I am not sure that it is directly that. But it certainly links back to Frank O’Connor and the Cork short story, yes. A lot of my poems are kind of short stories manqu I think. Some of the better poems really are shrunken short stories – like ‘The Fool in the Graveyard’ and ‘Ter Conatus’ I suppose. But there was still a lot of storytelling in the Irish countryside in the 1950s. Our neighbour Kate Mac (the woman in whose house we still spend the holidays) was a great teller of stories. But then she read Tess and English women’s magazines about the Royal family. And one of the most successful acts on Irish radio in the 1950s were the stories told by the seanchaí (roughly meaning ‘traditional storyteller), the great actor Eamon Kelly. His stories were a wonderful mixture of wit and the everyday and the medieval surreal. So there was a lot of it about, yes. It was reinforced by medieval literature again: I love the title of A.B.Lord’s book about local storytelling and epic, The Singer of Tales.

William Bedford: There’s a rich variety of linguistic registers in these poems, and the storytelling is obviously aided by the vernacular – ‘I stopped the once’ and ‘“You have the Irish well”’ for instance. Are these conscious literary choices, or do you still hear the rhythms and idioms of rural speech as you write?

Bernard O’Donoghue: Sometimes I hear them, yes. I worry that they can be a bit mannered, though. They are accurate enough reproductions I think – but they have to be used sparingly. ‘You have the Irish well’, is a kind of parodic version of what native Irish speakers traditionally said to compliment the schoolchildren who were packed off to the gaeltacht for the summer holidays. It is beautifully evoked in Heaney’s prose-poem ‘The Stations of the West’. It was said that the visiting children were called the ‘lá breá’s – ‘fine days’ – because that was the extent of their Irish. I do find the survival of non-standard expressions in colloquial usage very tempting.

William Bedford: There is a good deal of cruelty in the rural life explored in The Weakness: the black humour of ‘O’Regan the Amateur Anatomist’, the viciousness of hare coursing in ‘The Saga of McGuinness’s Dog’. But these are deeply humane poems ‘Ashamed of the binocular intrusion,/Like breath on eggs or love pressed too far’. Is there any sense of personal catharsis in work such as this?

Bernard O’Donoghue: Yes, I think so – or a kind of collective, social catharsis. Country life is extremely brutal. There is an (English) joke, about the sheepdog-trainer on One Man and his Dog, who is asked to what he attributes his extraordinary success in training the dogs? He replies ‘It’s simple really. It just takes a little bit of kindness – and a lot of cruelty.’ That is particularly what children growing up in the country witness. Indeed until recently it was what they experienced. The fashionable line to teachers from parents was ‘Give them the stick and plenty of it’! All in the Bible, of course. My poem on this subject is ‘P.T.A.’ in The Weakness. This is not a virtue or even a moral position, but I have a fear and loathing of violence that amounts to pathology I think! It makes it impossible to watch Tarantino or those ‘Girl with Tattoo’ films and so on. I think that dates from a country childhood. Arendt’s thing about the banality of evil: I think violence is the most banal and depressing form of it. I am full of despair about the readiness of the West – us – to bomb the Middle East, those great cultural centres like Badhdad and Tripoli as a norm of policy nowadays. Violent aggression and assassination seem to be first responses at the beginning of this millennium. Why is nobody objecting?

William Bedford: Gunpowder won the 1995 Whitbread Poetry Prize. The dust-jacket talks of these poems drawing ‘once more on incidents and episodes’ from your upbringing in County Cork, but ‘now on a more personal level.’ Is that something you were conscious of, perhaps a decision growing out of creative confidence? You must have been encouraged by the way your work was received from the start.

Bernard O’Donoghue: Mystified, is the word. I think when you write in private, on your own, although you have some kind of ideal readership in your head, you don’t really imagine anyone else reading what you write. In fact I think it might pervert it if you did. But I have never worked out a gracious way of responding to people who say they have read a poem of mine and liked it. Heaney does it beautifully again: ‘God love you!’ he says. I don’t think that I thought about those poems as more personal either. I think the best poem there ‘The Iron-Age Boat’ was the most impersonal, the best founded in its landscape.

William Bedford: We do tend to look for ‘development’ in our writers and artists – rather artificially I think – but I wonder whether you saw this collection in that light?

Bernard O’Donoghue: I didn’t really. I often think that people often give credit to the following book as it were: maybe the more substantial stuff in The Weakness was rewarded by an accolade to the next book. I like the last poem in Gunpowder – ‘Metamorphosis’ – and that is pretty personal.

William Bedford: You quote Norman MacCaig for the epigraph to Here Nor There, published 1999: ‘Something to do with territory makes them sing.’ And the dust-jacket shows a detail from Bicci Di Lorenzo’s St. Nicholas rebuking the tempest from the Ashmolean collection. As a matter of interest, three of the four Chatto & Windus collections feature works of Medieval art. You clearly had a say in that decision?

Bernard O’Donoghue: Yes, I chose the pictures and the Chatto designers did a wonderful job with them. The ‘St Nicholas’ has always been one of my favourite pictures – something that many people in Oxford claim. Someone pointed out that the cropping of the painting means that the mermaid has been cut out, but neither I nor the designer planned that. It may have some significance that we didn’t notice though. I think the MacCaig line is wonderful too: birds of course, but it has the same universality as ‘The Singer of Tales’ – music expressing attachment to place. MacCaig is a marvellous poet: he died the day I got the Whitbread prize which took the shine off it a bit. He was the pride of the Chatto fleet.

William Bedford: With Here Nor There, the title, the epigraph, and the Di Lorenzo detail all concentrate our attention on the idea of exile. Well mine, anyway. You’ve written about Dante as ‘the great “inner émigré”, the poet of the Ovidian tristia of the exile’. Ovid, Dante and Mandelstam are the great examplars of exile. I wonder whether the idea of exile is becoming more central to you with this collection, especially as the opening poem ‘Nechtan’ has Bran and his companions ‘fated/To sail for ever in the middle seas, outcast/Alike from the one shore and the other.’ Am I making too much of this?

Bernard O’Donoghue: Certainly not: you are entirely right. The book is consciously about exile. In fact that was the first of my books that had a coherent overall title I think. The problem might be that I’ve got a bit stuck in the groove. Everything has been about exile since. It is a capacious subject though: there are so many things we are exiled from – not just place. People, youth… I remember the moment I chose the title and its poem, ‘Westering Home’, driving west through Wales on the way to Ireland. I liked the rather mannered suppression of the ‘Neither’ at the start. If ‘neither here nor there’ means ‘insignificant’, then the removal of the negativing word at the start must mean that the surviving bit means ‘not insignificant’, therefore ‘important’. QED. I suppose I think of exile as a kind of creative privation too, in sharpening emotional consciousness of what has been lost, what we are exiled from. It is largely Ireland of course in my case. The great statement (as often) is Yeats’s: ‘Does the imagination dwell the most / Upon a woman gained or woman lost?’ The imaginative figure in ‘The Tower’ is ‘impatient to be gone’: the answer is too obvious to need giving.

William Bedford: Outliving, the last of the Chatto & Windus volumes, published in 2003, closes with one of the bleakest poems I think you’ve published: ‘The Mule Duignan.’ I’m not clear whose experience is being voiced, but the poem recreates a child’s distress at seeing his parents’ anxiety, and an adult’s anger at a way of life which produces such anxiety:

‘I hate that country:

its poverties and embarrassments

too humbling to retell. I’ll never ever

go back to offer it forgiveness.’

Even if the circumstances are not autobiographical, the feeling seems to be personal. Could you say something about that?

Bernard O’Donoghue: I think you have said it all, William! It is not of course autobiographical, but it is decidedly personal. (I have just written something about this poem in The Reader). My friend the Irish builder and musician Mick Henry tells wonderful and heartbreaking stories of the hardships of the lives of the Irish labourers in England in the 1960s and after. One of his most haunting is the story of ‘The Mule Duignan’ (real nickname). The poem is only a slight elaboration of the narrative exactly as Duignan told the story to Henry; the central declaration ‘if the cow does die tonight, we’ll have to sell up and go’ is verbatim from the narrative. That is partly why it is in speech marks. What I am saying I suppose is that nostalgia is an indulgence. You have to be reasonably well-off and comfortable to feel wistful about the locale of the poverties of your origins. Those labourers were forced out of Ireland by poverty; that is what Duignan does not forgive.

William Bedford: The title Outliving clearly invites reflection, and not just on the literal ‘outliving’ experienced in the first poem, ‘The Day I Outlived My Father’. Titles are gifts from writers, or ought to be. I have the sense that you usually have something ‘in mind’ with your titles?

Bernard O’Donoghue: Yes, particularly since Here Nor There: they were slightly more hit-or-miss before that (like Poaching Rights which I like as a title, but I am not sure what I meant by it.) I like Outliving as a title because I think it encapsulates several things I wanted to say with it. The title poem’s sense of ‘living longer than’; but also – a bit like the Mule Duignan again maybe – the good fortune of living a higher quality of life: more affluent. Also I suppose living outside the native terrain. I like living in England but I am always slightly abroad here. As I said already, that has positives as well as negatives to it. An early poem called ‘The Migrant Workers’ (only in Poaching Rights I think ) is about this:

There’s pleasure in saying ‘I live somewhere else;

My topography is more than meets the eye’.

So ‘outliving’ is all that too.

William Bedford: Were you translating Sir Gawain and the Green Knight whilst teaching the poem? I suppose I’m wondering how a tutorial would differ from the task of translation? Are there two distinct processes going on here with the word translating?

Bernard O’Donoghue: That is interesting. I translated Gawain more or less incessantly between 1966 and 2011, so I had a pretty full version in my head before I began the Penguin translation. It was different, yes. A tutorial translation has got to get the full literal sense of the original words – or as near as possible to that. The ‘verse’ translation aims more at capturing the spirit or implication of the original: the connotation rather than the denotation, or something like that. I found it difficult to bring it to life I think. But that may just may be a measure of how much I revere the poem. I found it easier to be satisfied with the bits of Piers Plowman I have done (though I revere that too). I think the translation I am least dissatisfied with is ‘The Wanderer’ in Farmers Cross. I think I am not a ‘great translator’ – unlike Chaucer!

William Bedford: Has Pound’s practice as a translator been important to you. Particularly a poem such as ‘The Wanderer’ and one of my favourites from Outliving which isn’t actually in the Selected Poems, ‘Love’s Medium.’

Bernard O’Donoghue: Pound really was a great translator: in fact I think he was the greatest translator in English since the sixteenth century. What Pound does is to reserve the right to move away from the literal sense of the original, but to keep a full sense of the original’s impact in a version that even resolves cruxes of interpretation. His translation of Cavalcanti’s ‘Donna mi prega’ would be my nomination for the greatest translation of a short poem in English. ‘Love’s Medium’ was written for the wedding of two ex-students of mine. It is loosely based on the Anglo-Saxon ‘Wulf and Eadwacer’, one of the great obscure love-poems in English (if that is what it is). My poem has a couple of good ideas in it (like the man chopping a tree making wood). I think maybe I thought it didn’t hang together well enough to make the Selected. But I am glad you like it! It would have provided an opportunity to correct that ‘it’s’. I suspect that I rejected it for the Selected because I was in denial about that possessive mark.

William Bedford: You moved to Faber & Faber with the publication of Farmers Cross in 2011, and that volume has an interesting epigraph from Basho: ‘Of all the many places mentioned in poetry, the exact location of most is not known for certain.’ This is a collection which is full of wanderers and refugees, across cultures and histories. I love the way ‘History’ has an epigraph from Aelfric’s preface to The Life of King Edmund, and yet takes us down the years from Abraham Lincoln’s funeral to your own childhood and – I assume from the poem’s ‘you’ – the childhood of your own children. This is a long, and moving because so long, historical perspective.

Bernard O’Donoghue: I am very keen on the Basho epigraph. It comes from one of my favourite books (in fact it might be my very favourite book), Narrow Road to a Far Province, written in late seventeenth-century Japan and describing the wanderings around Honshu by a couple of poets in old age. The idea is echoed in Farmers Cross by Petrarch’s Ascent of Mount Ventoux from which I have taken the epigraph for my George Watson elegy ‘Ascent of Ben Bulben’. As he is getting older Petrarch decides he would like to see the view from the top of Mt Ventoux, but deliberates about who he should travel with, reflecting ‘so rare a thing is absolute congeniality in every attitude and habit even among dear friends’. Farmers Cross is not about exile as Outliving was; it is about ageing: a topic I find increasingly compelling! Travelling in preparation for the end…

William Bedford: I think there is a definite sense of ‘first and last things’ in Farmers Cross. That the poems are not just reflecting on ‘life’, but your own life. We’ve already mentioned the theme of exile in the first poem, ‘Bona-Fide Travellers’, and the last poem is a beautiful elegy to a lost friend, ‘The Year’s Midnight.’ You do have a remarkable gift for letting the visionary shine through the apparently prosaic detail, as in the very last line of this poem: ‘and the shades fell not long after 3 p.m.’ That’s a risky dying-fall, but such endings always work with you. You obviously take great care with the arrangement of your collections, the opening and closing poems clearly being very important?

Bernard O’Donoghue: I am glad you think that dying fall gets away with it. I think in books, as with readings, you have to give thought to the first and last items: eschatology again! What comes in between is less crucial. I should say that Matthew Hollis was enormously helpful in arranging the poems in Farmers Cross. I remember Helen Farish helping a lot with the order too: she suggested putting ‘Bona-Fide Travellers’ first. That book is very personal, it is true: drifting close indeed to the confessional that I have rather grandly abjured.

William Bedford: Are collections clearly themed in your mind as they develop, or simply accumulations of poems, the themes developing out of the process of writing? I’m thinking of Eliot’s remark in ‘The Three Voices of Poetry’ that he doesn’t ‘know what he has to say until he has said it’?

Bernard O’Donoghue: Or whoever said ‘how do I know what I think until I hear what I say?’ It is exactly as you describe: you gather the poems together and see what they amount to by the end: try to impose a collective theme on them. Titles are very crucial I think. Think of things like The Waste Land or Yeats’s The Tower or Heaney’s North. There are risks of course: titles can be a bit procrustean. When I told John Fuller over the phone that I had settled on The Weakness as a title (it was suggested by my daughter Ellie and endorsed by Mick Imlah who was my Chatto editor), John paused briefly and said ‘Yes. It’s a brave title, isn’t it.’ – which was quite right. I think what is happening now is that my life has caught up with my titles: I rather stymied myself by banging on about death when I was young (‘Razorblades and Pencils’ and all that), so that it is hard to see where to go after ageing now. ‘The only end of age’, as Larkin cheerfully says.

William Bedford: It seems to me that your most powerful poems often begin with an ordinary event or anecdote, before opening out into a moment of startling metaphor or epiphany. Assuming you accept the word at all, I wonder whether you understand the idea of epiphany in the traditional religious sense, or as Joyce’s secular ‘revelation of the whatness of a thing’, which always sounds like Hopkins’s or Duns Scotus’s ‘thisness’ or haecceitas to me?

Bernard O’Donoghue: That is very interesting. I think I like to begin with an event or an image and then see what it can be made to mean. My favourite TV moment of 2011 was the girl in the magnificent Educating Essex who said wonderingly ‘What is pi? Where does it come from?’ – certainly the question of the year. I think my epiphanies are closer to the religious sense than Joyce’s (which are mischievously elusive anyway – Gogarty asking to have his sausages delivered. What is that about?). It is back to the Anglo-Saxon elegies yet again – ‘wisdom and experience’: the moral sense that can be drawn from something. Metaphor is part of it too, that’s true. The language has to work. I am not confident that mine always does. Everyone knows the occasional moment of triumphantly throwing the pencil on the floor because the last line has come out right. The opposite experience is commoner!

William Bedford: Has the Catholic faith been a continuing part of your life? You’ve mentioned St Ignatius, St Teresa, The Cloud of Unknowing, Evelyn Underhill, Thomas Merton in passing, when talking about Heaney. But a lifetime teaching Medieval literature must have brought you close to Walter Hilton’s The Ladder of Perfection, Richard Rolle’s The Fire of Love, Julian of Norwich’s Revelations of Divine Love, the volumes of Middle English religious prose. It’s a rich spiritual and linguistic inheritance.

Bernard O’Donoghue: Yes indeed – not to mention Dante, bizarrely everyone’s preferred poet in the post-faith twentieth century. Catholicism has been incalculably important to me of course – I don’t know how much it infiltrates everything. Certainly the kind of rich and metaphorical language that I respond to – and the sense of life lived seriously. I think I am not exactly spiritual by disposition though. Maybe seriousness about the world strikes me as the greatest virtue, as I have. We only get one go at life, so we have to make sure it tells.

William Bedford: You have elsewhere asked yourself the question ‘what exactly is meant by “an Irish poet”?’ It’s a complicated question, and I wonder whether you are any the clearer as to an answer?

Bernard O’Donoghue: No, I am not. There are all kinds of unhappy definitions that I don’t accept though. An Irish poet is someone born in Ireland who takes Ireland as a subject some of the time. I think Edna Longley’s warning is salutary: Ireland is not a good single diet for the Irish poet. But there is so much that is enriching about Ireland: the landscape, its sociology (as represented by Joyce or Frank O’Connor), its mixture of the secular-pagan and the numinous. No, I still don’t know. But I am very proud to claim Irishness, poet or not.

William Bedford: We’ve been talking about the idea of exile, and it is there throughout your poetry and in many of the responses to your poetry. But Poetry Ireland Review made the point that although you are clearly ‘an Irish émigré poet’, your work seems ‘refreshingly without the anxieties and hang-ups of the exiled, displaced expatriate, revelling instead in his freedom to inhabit more than one place.’ Your title Here Nor There seems an affirmation of that? It would be a fine celebratory note for us to end on.

Bernard O’Donoghue: Yes, I would like to end with that. I am not the best or most experienced citizen of the world, but I do think that living where we are now is the thing to be seized on gratefully, always. Virgil and Dante are very poignant lamenters of the tragic figures who revoked their ‘share of sweet life’. The Mule Duignan is maybe wrong to feel bitter about the Ireland of his childhood; but he is right to settle for whatever the here-and-now offers. And Here Nor There is meant to be positive in just that way: cautiously rejecting the negative and the insignificant. Best foot forward!

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The Courtly Love Tradition (ed.) (Manchester University Press, 1982)

Thomas Hoccleve: Selected Poems (ed.) Carcanet, Fyfield Books, 1982)

Razorblades and Pencils (Sycamore Press, 1984)

Poaching Rights (Gallery, 1987)

The Absent Signifier (Mandeville, 1990)

The Weakness (Chatto & Windus, 1991)

Gunpowder (Chatto & Windus, 1995)

Seamus Heaney and the Language of Poetry (Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1995)

Here Nor There (Chatto & Windus, 1999)

Oxford Irish Quotations (ed.) (Oxford University Press, 1999)

Outliving (Chatto & Windus, 2003)

Zbynĕk Hejda: A Stay in a Sanatorium and other poetry (translator) (Southword Editions, 2005)

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (translator) (Penguin, 2006)

Selected Poems (Faber & Faber, 2008)

Farmers Cross (Faber & Faber, 2011)