*****

James Harpur has published ten books of poetry, including The Gospel of Gargoyle (Eblana Press, 2024) and The Oratory of Light: Poems Inspired by St Columba and Iona (Wild Goose, 2021), both with artwork by Paul Ó Colmáin. He has won many prizes, including the Michael Hartnett Prize, the Vincent Buckley Award, and the UK National Poetry Competition. His debut novel, The Pathless Country (Cinnamon, 2021), won the J.G. Farrell Award and was shortlisted for the John McGahern Prize. He is a member of Aosdána and lives in West Cork. www.jamesharpur.com

*****

Introduction • Review • Poems

*****

James Harpur on the genesis of his Gospel of Gargoyle

My Gospel of Gargoyle was born out of crisis and featured a mysterious voice. The crisis was Covid in early 2020, which had a profound effect on me. I was knowledgable about the Black Death in Europe in 1348, and had even written a poem about it through the voice of the real-life Father John Clyn of Kilkenny, who left an unfinished chronicle, his last two words being ‘magna karistia’, ‘great dearth’. The Black Death came from the East and suddenly turned up in Italy through the natural movement of traders. In early 2020 there were reports of a virus in the East, then suddenly it was in Northern Italy. I knew that a third of Europe had died in the Black Death, the equivalent of 250 million people today. In Ireland, as elsewhere, restrictions came in; police monitored movements; masks turned friendly faces into aliens; people could lie down on empty motorways; the country had about 500 ventilators in public hospitals.

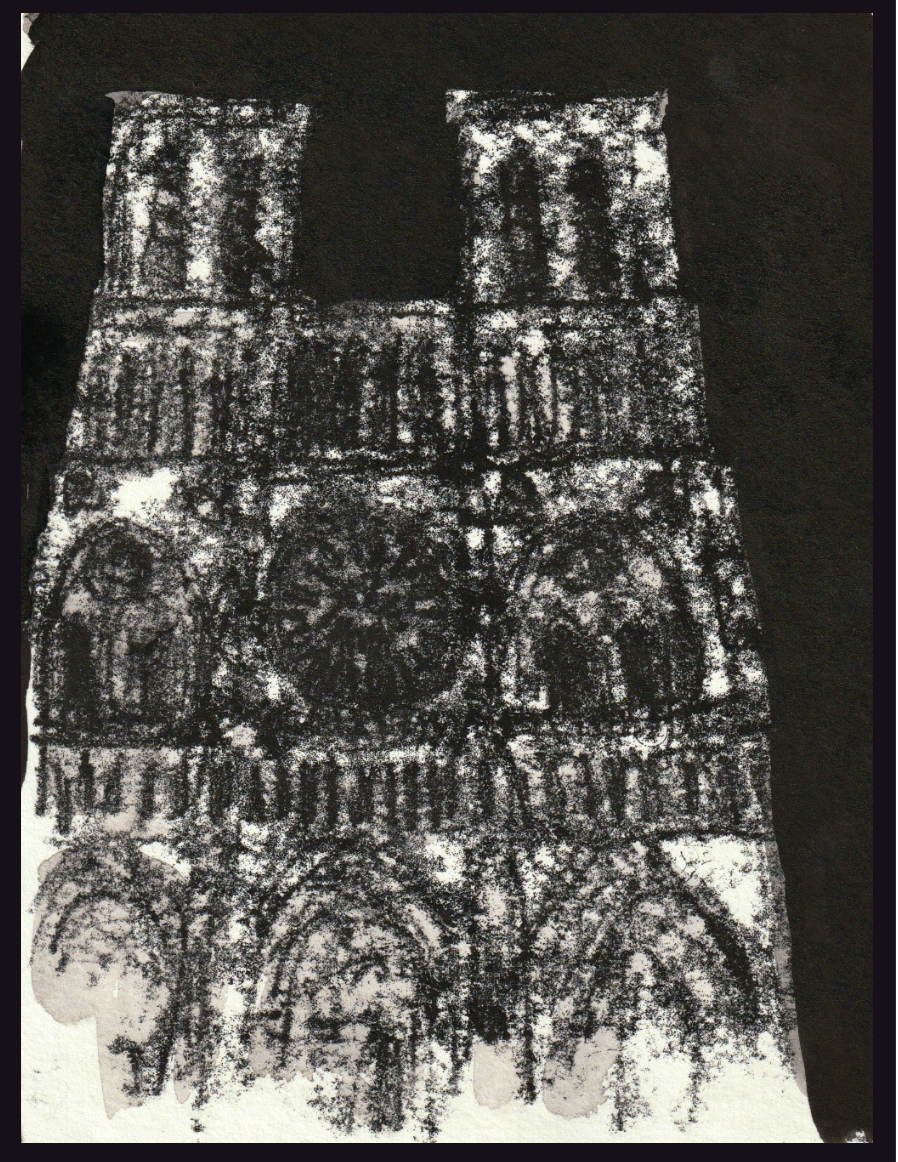

Very soon I began to have powerful intense dreams, with at least two involving exorcisms of some evil spirit which had me waking up and shouting. Then one morning I woke up with the words, ‘Poets do not come here any more’ on my lips, apparently the words of someone who had spoken to me in a dream. I knew instinctively that if I followed the thread of these words they would lead me, like William Blake’s golden thread, to the Jerusalem of a poem of some sort. But I was powerless to do anything about it; I had to wait for another dream to come along. And eventually it did, and of all places it took me to Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris. I had had a writing residency at the Irish College in Paris in 2018 and Notre-Dame had become an old friend, a building I would pass almost every day on the way to somewhere or other. I would linger outside or saunter inside to savour the atmosphere. During the great fire of 2019 I remember the visceral shock and grief, as if a civilisation had gone up in flames; Then there was the archbishop of Paris, Michel Aupetit, declaring just after the fire that Notre-Dame was not a museum, it was a soul.’ It was as if a piece of personal history had gone up in flames. Paris has great resonance for me. It was where my mother was born and raised, and tales of her French childhood had become part of my family lore.

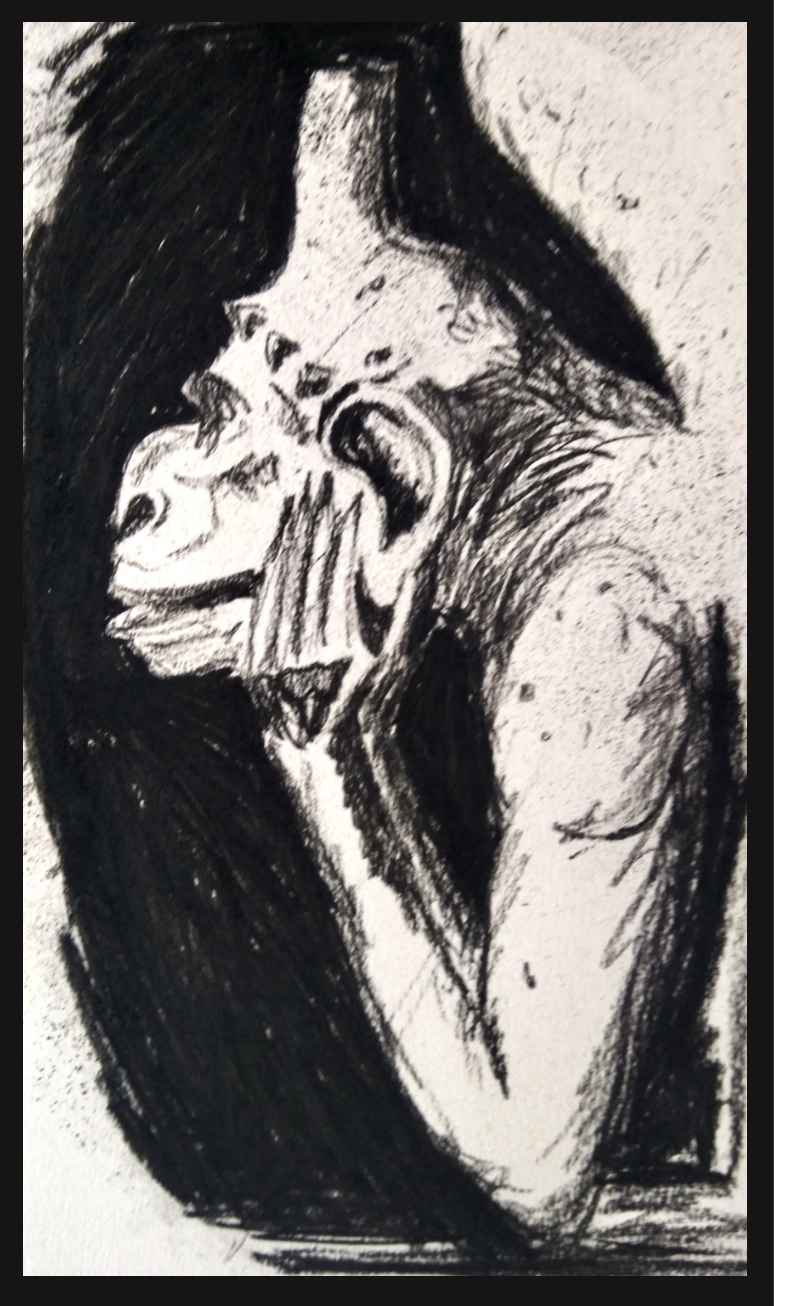

In my dream I flew to Notre-Dame – I have flying dreams from time to time, in which I fly backwards to places – and landed on the rooftop. There I saw a gargoyle, a particular one, known as Le Stryge, or the Witch, and the gargoyle winked at me and said, ‘Poets do not come here any more’. I woke up after that, but crucially I had established a connection with something beyond my personal consciousness. As Jung said about Philemon, in Memories, Dreams, Reflections: ‘Philemon represented a force which was not myself. In my fantasies I held conversations with him, and he said things which I had not consciously thought. For I observed clearly that it was he who spoke, not I. He said I treated thoughts as if I generated them myself, but in his view thoughts were like animals in the forest, or people in a room, or birds in the air, and added, “If you should see people in a room, you would not think that you had made those people, or that you were responsible for them.”’

In a similar vein, over the succeeding weeks and months. Gargoyle became, in Jung’s words, ‘a force which was not myself’, a voice with its own personality, back-story and motivations. I guess this is in a way not saying more than what any poet or author would claim: their characters are autonomous. But Gargoyle appeared only when he wanted to; sometimes I would meet him during the course of a flying dream, when I would be transported over Paris at nighttime, always at nighttime, and sail past the dome of the Pantheon and land on the roof of Notre-Dame. Sometimes I meditated on him, in the manner of a Benedictine monk, for whom the practice of meditatio (as opposed to contemplatio) involved the steady focus on a biblical text or religious work of art, letting the sacred words or object self-amplify. Sometimes I would use active imagination, or my version of it, a sort of deliberate abandonment to daydream, allowing words and images to emerge without taking too much deliberate heed of them, in case an exacting attention might impede their creation; and sometimes I would enter what Ted Hughes has referred to as ‘the sacred trance’, akin to meditation and active imagination, but with perhaps more discipline and focus. If something or someone wants to contact you from the beyond, it makes good sense and is good manners to be quiet in the mind in order to listen to them.

So, what did Gargoyle have to say to me? I say ‘me’, but the Poet character that ended up on the page was not exactly me, but a poet figure who shared a lot of my characteristics but who was not identical with myself, in as far as I was able to tell the difference. Of course, in any artistic creation there is a sense that all the elements originate from an author, but some seem more under conscious control than others.

Over weeks and months scenarios and dialogues between Gargoyle and Poet appeared, all set on the rooftop of Notre-Dame. In the story that emerged, Poet and Gargoyle gradually come to know each other better, and they find they need each other. Poet for his part is obsessed with knowing who or what caused the great fire of Notre-Dame in 2019, an obsession I also shared. He thinks that Gargoyle must know the cause of the fire and pesters him for answers. The fire itself becomes part of the quaternity of characters in the book, along with Poet, Gargoyle, and Notre-Dame; and fire itself is a running thread, recalling one of the book’s epigraphs: Heraclitus, Fragment B30, ‘This universe … has always been, and is, and will be ever-living fire.’ So what does Gargoyle want from Poet? His opening statement, ‘Poets do not come here any more’ is provocative and suggests a time when poets did come to Notre-Dame and the world of gargoyles, a mythic realm that the poets have now abandoned.

*****

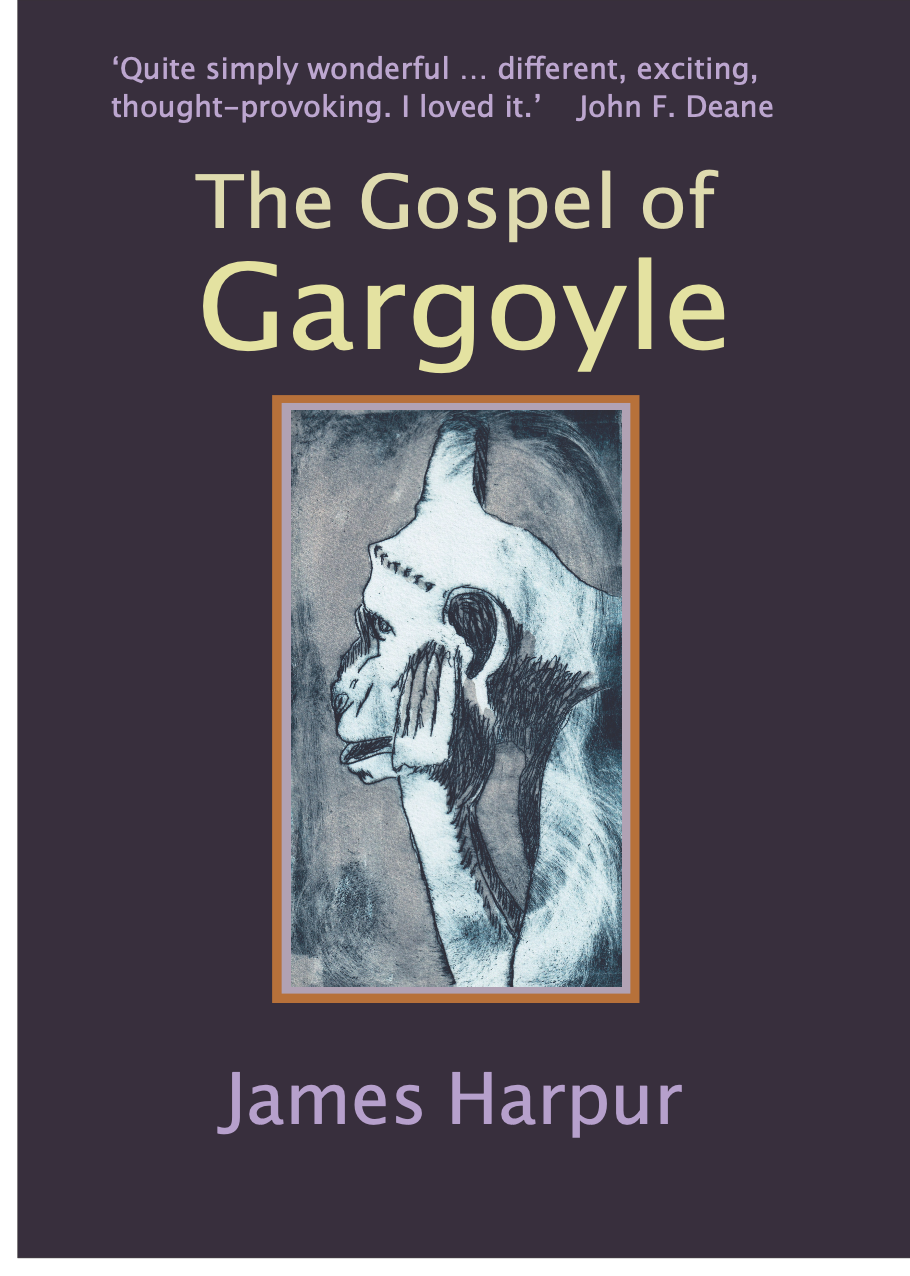

The Gospel of Gargoyle by James Harpur. With artworks by Paul Ó Colmáin. €20 incl. €5 p&p. The Eblana Press. Reviewed by Patricia McCarthy

This modest-looking book by distinguished multi-award-winning Anglo-Irish poet James Harpur from Eblana Press makes you hold your breath. It illuminates the plight of any outsider in society and as such is so relevant to our times. Huge in vision, it is a very special original, ambitious work of epic proportion, worthy of its great antecedents Dante’s Paradiso and Milton’s Paradise Lost. To read it is to have a unique experience on different levels – of visionary poetry where the focus is on the elimination of the self, on trying to understand our very existence and our attempts to ‘make the infinite finite’, of lyrical poetry startling in its imagery and of carefully crafted narrative poetry… All in all, The Gospel of Gargoyle defies categorisation: it is too interknit to be called a mere ‘collection’ – even if the poems can be read as stand-alone poems.; it could well also be a unique enlightening drama for the stage.

The architectonic framework of the sequence serves on the surface as a kind of detective story, subtly told also by Paul Ó Colmáin’s accompanying artwork, as to who started the fire in Notre Dame Cathedral in 2019. It is mainly a dialogue between the ‘Poet’ who, at a remove from James Harpur, serves as his mask or alter ego – and who has dream flights, via Harpur’s use of magical realism, to the gargoyle on an outside parapet of Notre Dame after the fire – parallel with the gargoyle’s being anthropomorphised. The dialogue serves as a very subtle device by means of which Harpur can inject his own holistic learning into the text as he answers the gargoyle’s increasingly demanding questions, thus driving the narrative along and giving it its dramatic edge. The reader is taken on the bigger quest, with the two main characters, to find the meaning of life, if there is one, and to try to solve the mystery of the afterlife.

It would be interesting to compare and contrast the Gospel of Gargoyle with Eliot’s Four Quartets which both represent a journey to enlightenment – Harpur, dare it be said, having a more eclectic range of sources up his sleeves than Eliot. Eliot himself contended that the highest ‘for civilised man’ is a poetry that unites ‘the profoundest scepticism with the deepest faith’; and, very broadly interpreted, Harpur manages exactly this. The gargoyle is very carefully delineated to represent, in Jungian terms, Harpur’s shadow self by means of which Harpur can express his and most people’s doubts as to faith, and to the meaning of mortal life on earth. This results in an intense dialogue between the two parts of himself: the learned spiritual mentor and the sceptic. Although Harpur himself is steeped in mysticism, Buddhism, Krishnamurti – and Christianity, unlike Eliot there is nothing declamatory in his approach. His ‘deepest faith’ amounts to a profound spirituality not rooted in one particular faith but in many – proving him to be not only a poet for all times, but a poet of our own times. Harpur’s references from diverse cultures, faiths, rituals, countries and ages challenge the reader to face the big questions of human existence along with the Poet, the gargoyle, and James Harpur himself when he intervenes occasionally with the autobiographical ‘I’.

In fact, Harpur could be mocking the whole business of the I, personal or otherwise, in poetry, since the different personae here are all, in a way, Harpur himself. He does enter with the autobiographical ‘I’ sparingly at the beginning and end of the work – as a student in the Irish University in Paris who ignores the beggar he passes on the streets, and towards the end of the sequence when he stoops down to shake the same beggar’s ‘big tobacco hand’ that he can’t let go, intimating that everyone shares the same human predicament and doubts, no matter how lowly their status. At one point, using the autobiographical ‘I’, Harpur even questions whether he fits into this world

…wondering if I chose the wrong life

As if I’m part of a cosmic jigsaw

That has no picture on its box.

This work is eminently suitable to be a performance on the stage as a drama with its patterning, its changing rhythms and pace, and with the very short interludes of a few lines between the dialogues which would serve as stage directions – slightly reminiscent of a Beckett play but less bleak – with some lines that are repeated for their echoing effect, and powerful lyrical passages. Of course the dramatic suspense – even the near suicide of the Gargoyle at one point, adds to its theatrical impact. It is the ‘parapet’ on Notre-Dame’s exterior which features as an important, if you like, stage prop throughout, on which the gargoyle balances ‘staring into the nothingness of nothing’ – at times with the Poet when he visits him on his dream flights, and which serves as a trigger for the gargoyle’s unease, and even for his near suicide.

From the outset, lending an emotional tone to the piece, Paris is personified: it ‘sulked as if it bore a grudge/Against Lent’, Lent, leading to Easter, being the liturgical time in which the sequence is set;. It is hard not to think of Rainer Maria Rilke as a young man in Paris – like Harpur finding it very busy but enjoying the contrasting peace inside Notre Dame Cathedral. Indeed, Paris, with ‘The liquorice sluice of the Seine’ is another kind of character whose various districts visited by Harpur, or seen by him – and the gargoyle from up high on Notre Dame’s parapet, we get to know. We are taken around. Montparnasse cemetery which seems to have ‘emphysema’ – trying to breathe perhaps for the ‘lost spirits looking for a home/or meaning… never found on earth’ (like the ‘Poet’, Harpur and the gargoyle) where Harpur himself sees the graves of ‘atheistic stryges’ of Beckett , and Sartre whose stone slab is ‘peppered with métro tickets’, Sartre’s existentialism that denied the crutches of religion or hope come to no more (and here Harpur shows his humour) than ‘métro, boulot, dodo’.

Harpur, the visiting student, becomes, as the narrative progresses, indistinguishable from the Poet of the main dialogue, just as the Poet and the gargoyle, that ‘lump of stone’, seemingly so opposite, ironically become similar, saddled as they are with the human predicament. The beginning and the end of the sequence shows them linked in their search for the proper light of enlightenment, or redemption, waiting

For Light

That comes invisible as breath

Then breaks in like a burglar in the night…

And finding, later on, ‘a true reality of light’..

By letting go the sense of self –

It’s like committing ego-suicide –

You’re diving into every moment of life

As if you’re jumping off a parapet…

Into the weightlessness of the unknown.

Change is a constant theme; even the two main protagonists are in a state of flux as the sequence proceeds, the persona of the Poet (as we have seen) at times actually being James Harpur, the author, and the gargoyle ‘just a lump of stone, a statue’ ‘under some curse’ who manages nevertheless to articulate very movingly his plight, becoming more and more human, with the power of his language, his little narratives within the larger narrative, demonstrating, like Shakespeare’s Caliban, lyricism and a natural kind of intelligence by which Harpur implies no one should be too quick to judge another. At the outset the gargoyle even asks big questions re the origins of the stars and fire, of life, blending into the autobiographical I of Harpur at the end sections when it becomes hard to distinguish the gargoyle’s voice from that of the Poet or of Harpur. The language changes too and becomes more prayerful at the end. Even the solid structure of Notre Dame Cathedral– whose erection is described by the gargoyle who witnessed it when in a previous life – becomes a ‘Church of Air’.

In this Church of Air, Harpur glides, as if still flying but differently, through his memories, alternating between specific places with names in Wiltshire and Ireland. He pictures his Irish father on his ‘corpses of pillows’ in Ireland, and his English mother in Wiltshire making watercress soup which was kept in the freezer after her death ‘daring us to thaw her memory away’. Harpur uses architectural parts of a church such as the nave which is a ‘nave of air’, the transepts which are ‘the garden of Reagh on Sliabh Bawn’, and so on. His memories of real family life pass through, it seems, the different stages of the Mass adorned with beautiful lyrical language. The choir is his ‘April garden at home’ where swallows’ tails ‘flick/ Like slick batons of conductors’. The altar ‘is our kitchen table’ covered with the ‘clutter’ of ordinary everyday things, the Host (communion bread) is in the ‘china tureen’ which holds his mother’s soup. As the choir of birds continues, ordinary time recedes, giving rise to an epiphany that records ‘The utter strangeness of existence/ The mysteria, the unexplainables/Of love, beauty and coincidence’ and leads to prayers for the sick and infirm, ‘Not knowing if our prayers will succeed’ – a creeping doubt perhaps about the Poet’s confident definitions.

Harpur very subtly and comprehensively introduces his ‘ars poetica’ into the text. From the outset, the gargoyle keeps asking ‘what are poems for’, what is prayer, what is Love, who is God…, wanting the ‘Poet’ to ‘miraculise’ his ‘lumpen mind’ and this allows the ‘Poet’ to become a teacher/mentor, even a ‘saviour’, and to express in detail his ars poetica. The Poet tells the gargoyle ‘To make a poem you have to ease yourself/ into the pouch of silence waiting for you’…Leaving the silence, he says, you scribble your thoughts ‘till words are tingling in their syllables’….But first you must be light of heart/to make imagination quick, alert./Believe in nothing but possibility – Be free to rove the universe’. Only then

By letting go of everything you know,

Stepping from your old conditioned mind

And flying from the corpse of reason.

Then even you can make gold from grit.

What a wonderful lesson in how to make a poem – surpassing, I think, what Rilke said in his Letters to a Young Poet, also linking to what Michael Longley, in an abbreviated way, said of his own writing of a poem: he had to have a special lightness, almost without thought….

To Harpur prayers and poetry are inter-related. Despite the gargoyle calling prayers just ‘laments of the lost’, the Poet explains ‘prayer is less an asking than…/ A ‘stillness induced within yourself// By meditation, say, or pilgrimage’ and here he could be talking about the process of writing a poem. He goes on to describe a kind of Joycean epiphany: ‘As if your psyche whooshes and expands’ and –

You become more you by being less

Because the less there is of you

The greater is the space for God, the holy spirit:

You feel as if you can fly and tune into

Divine guidance and psychic fields

Of those who’ve also shed their transient selves.

In this regard prayer resembles poetry.

Like the ‘Poet’, the gargoyle is aware of his limitations: ‘I lack the wile or wit to inkle what my part is’, though he does hope in the power of poetry about which he knows nothing: ‘I’ve heard that poems turn darkness into light, stone into soul, ages into worlds without end.’ And the spiritual search for poems to do just this, aided by the explanations and lyrical definitions from the Poet serve just as urgently as the need to know who caused the fire in the Cathedral.

The gargoyle says he knows who started the fire but he won’t say: (partly because he enjoys the visits of the poet but also ‘I’ve learned there’s a malevolence in this universe who likes to change our lives at whim’. So, despite the gargoyle being derided initially by the Poet as a ‘clown’ with a paw and snout nose – who ‘sighs like a punctured tyre’ and coughs ‘an elongated growl’ – it is apparent that in his lowly state he has actually acquired some sort of basic learning and in the end gargoyle and the Poet become almost interchangeable, for example the gargoyle says, later in the text ‘As if your memories are now mine’. And even later when the Poet movingly comments

His blackened stone was cracked as if his soul

Or spirit had finally flown away.

It felt like an amputation of my self.

The more the gargoyle learns from the Poet, the more extreme his plight becomes, perhaps implying that unthinking man suffers less than his more enlightened counterpart. He not only begs ‘Teach me how to pray’ but also wants to ‘rid himself’ of stone. From here on the relationship between the two intensifies and deepens into a genuine friendship. And the gargoyle’s powers of self expression have increased enormously – so much so that he articulates a narrative , or a series of little narratives at various points, within the larger narrative of the whole, surprisingly lyrical and articulate about how the fire started (his words could come from the Poet’s mouth): he saw ‘grey feathers growing from cracks’, orange smoke’ – in response to the Poet urging him not to think – just ‘Let words come out… as if you’re spitting.’ After the gargoyle’s exhilarating description in short lines emphasising the speed of the fire taking hold with its ‘shrieks’ the gargoyle asks the stark question: ‘What is love?’ it is this for which he thirsts.

Again, the Poet gives a definition of ‘love’ ending with

… Love won’t stay as Love if self intrudes

And forms attachments, webbing the object

Of its desire: then Love transforms to ‘single love’

And narrows down its loving kindness,

Enters the world of mine and yours.

The reader/audience becomes so absorbed in this poetic drama that the answer to the question as to who started the fire becomes almost irrelevant. However, as Penelope Buckley in her Afterword states ‘the ending is a little electric shock’.

In general, this unique work illumines how we are all – not just the gargoyle and the Poet –‘lost spirits looking for a home’. At the outset, the Poet explains ‘The universe is interlinked – / Each tiny part connected to the whole, /And all contained in every single thing’. This surely applies to the whole of The Gospel of Gargoyle. One of the references in the book is to Gautama the Buddha who is rendered speechless in trying to ‘utter the wordless’, Here Harpur finds word after word for ‘the wordless’ to awaken the reader into full awareness.

Patricia McCarthy edited Agenda poetry journal for over twenty years. Her latest collections are Hand in Hand (based on Tristan and Isolde), 2024, a pamphlet from

Dare-Gale Press, Bad Summer, 2025 and Round the Mulberry Bush which is due to appear

in late Spring of this year.

*****

Four Poems from The Gospel of Gargoyle, with artworks by Paul Ó Colmáin

THE ANGEL OF CHARTRES

A fierce breeze tries to shove me back

Inside the train; but I resist and glide

Through sun-buffed, littery streets,

Cathedral towers playing hide and seek

As I turn a corner here, there, recalling

Rodin and Rilke arriving on a winter’s day,

Rodin abusing Chartres’s gothic scowls,

Rilke scarfed against the sleet of words,

The east wind embittering his eyes,

And his life in flux, marriage flailing;

And Rodin still relentless in his grousing

Until they turn the corner I now turn

And all at once we see

The angel

The slender angel low down on the wall

Who’s holding out an offering:

A semi-circular stone, a sundial

Dissolving time to a stick of shadow

That’s poised like a fishing float poised

To pull quicksilver life from flux

And if only for a moment tear

The spirit from the body

And raise it high

xxxxxxxxxxxxx shimmering

And wriggling

xxxxxxxxx xx into the element of air.

***

THE GOSPEL OF GARGOYLE

Blessed are the rooftops

xxxxx for they bear the weight of gargoyles.

Blessed are the gutters

xxxxx for they are the rivers of Gargoyle.

Blessed are the poets who believe;

xxxxx Gargoyle shall be their friend.

Blessed is the moonless night

xxxxx for it hides the plotted path to heaven.

Blessed is the wind

xxxxx for it blows chances across the way.

Blessed is the chimney smoke

xxxxx for it is the incense of the earth.

Blessed are the dogs that roam

xxxxx for they are the preachers of Gargoyle.

Blessed are the ugly

xxxxx for they shall remain ugly.

For in the world of Gargoyle

xxxxx there is no ugliness or beauty.

All are equal under the stars.

***

GARGOYLE DESCRIBES THE FIRE OF NOTRE DAME

‘Was staring into space. As usual.

I sniffed a rancid smell like smoke

And turning saw the strangest thing –

Grey feathers growing out of cracks

And rising higher from the roof

Sucked up by some great force.

A crowd below were looking up –

Tips of flame licked through

Like orange smoke – suddenly

I was aware, rapt –

Gold glare of window glass –

As if the sun was trapped inside

This dull cathedral carcass

Then shrieks of flame shot up –

O gloria I danced with glee!

Such ferox, fiery freedom –

My spirit yelping in its shell

As if inferno could force it

Into another body, another life.

Street-throng mesmerised –

Colossus of their childhoods! –

Great cot of memories! –

Its thorax threatening to crash.

‘Night sultrified, blue flicker

Of fire engines. Inferno roared,

Bateaux mouches slowed the Seine.

Such crowds, candles … I heard

Songs, as of mothers at a tomb,

Again and again the words rose high –

Viens, sois ma lumière, mon feu d’amour …

Donne-moi leurs âmes, j’ai soif d’amour!

J’ai soif d’amour.

I thirst for love.’

***

THE PANTHER

(at the Jardin des Plantes)

It takes a while before I see him

Up high on a step of concrete beside a tree trunk

Behind a shimmer of wide glass

That glances off your glance as soon as look at it.

He has folded up his life

His padded paws tucked in beneath the musculature of the sphinx

The ripple of his sandy pelt smudged

With sooty blotches and sealed

Into a velvet of perfection.

The slits of his eyes have sunk within

The heavy pentangle of his head –

He’s in a predator’s sleep

And dreaming about a moment-flash

On the northern plains of China –

And then as if he sees a thought scrambling for cover

His eyes have switched awake:

He turns his head towards the stalker –

And in a shock of contact

We are locked in a groove of power

I to I, eye to eye, until I

Blink

As if bolting for my life.

most fascinating, rich and deep. i look forward to reading more.

from a flying companion who attended James Harpur’s workshop at Exeter cathedral as he was a resident (between 1980-90)

LikeLike