*****

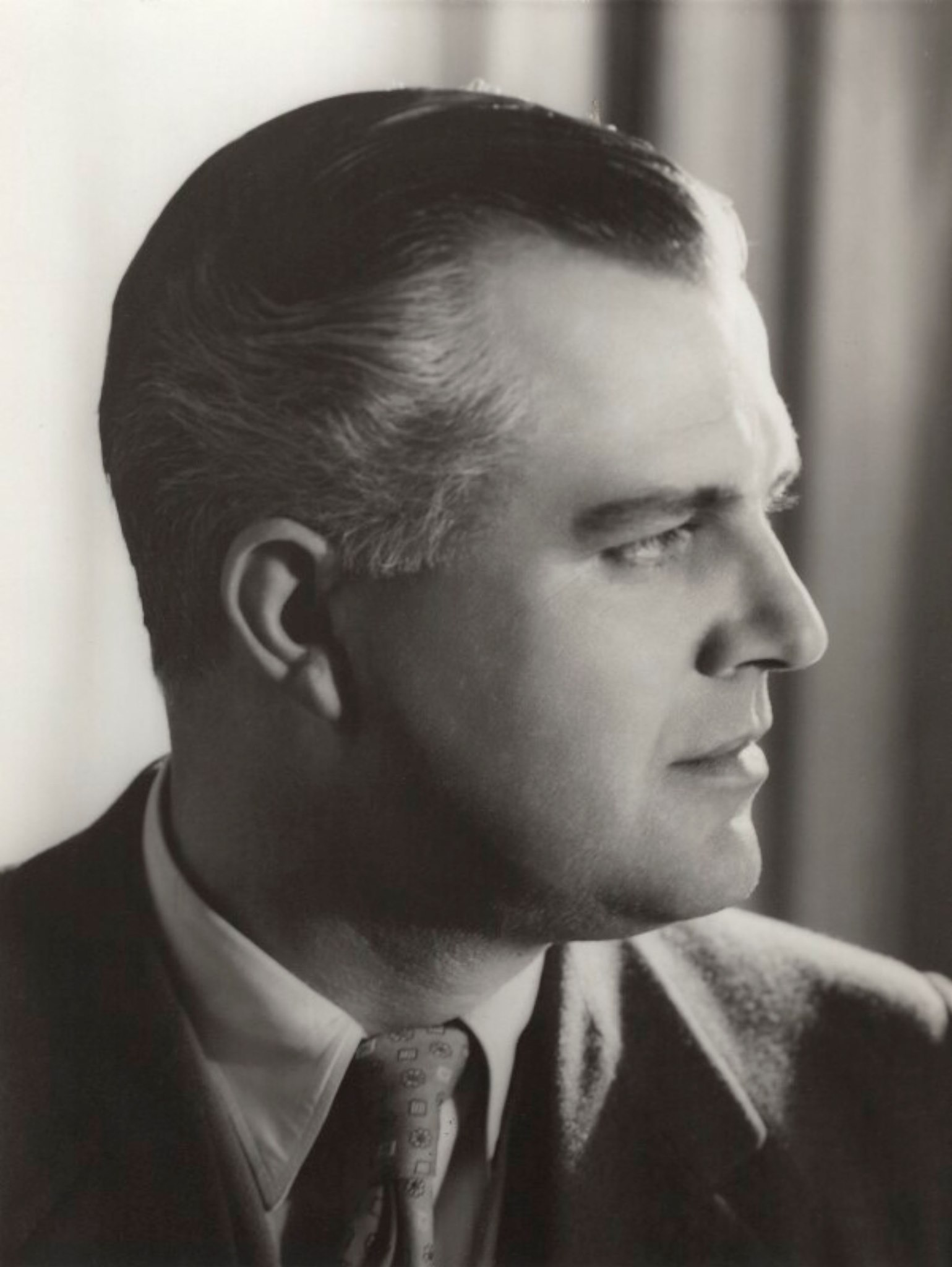

Christopher Hassall (1912-1963) was a poet, librettist, dramatist, and biographer who found early fame in his collaborations with Ivor Novello in the 1930s. Desiring to be a more serious writer, and supported by Edward Marsh, he turned to poetry winning the Hawthornden Prize for Penthesperon (1938), one of six published volumes. His poetry charted his experiences of the Second World War in which he served as an anti-aircraft gunner before becoming more philosophical and spiritual. His last, unfinished sequence Bell Harry (1963) was dedicated to his friend Frances Cornford and was a fuller expression of his Christian faith.

*****

Christopher Hassell: The Dancing Years, Selected Poems, edited by John Howlett

Marking a little over sixty years since his untimely death, this volume represents the first attempt to collect and appraise the poetry of Christopher Vernon Hassall (1912 – 1963). By drawing upon a selection of his six volumes of shorter lyrics, as well as representative excerpts from a small number of longer poems, it is thereby intended to stand as a corrective to those who today know Hassall best as a song lyricist, librettist, dramatist, and literary biographer, fields in which admittedly he excelled. Just too old and substantial to be a Bright Young Thing, he was likewise too obviously apolitical to be subsumed within the social concerns of MacSpaunDay. Most damning of all, the public patronage afforded him by Edward Marsh meant that Hassall never quite escaped a shackling association with the soon-to-be unfashionable Georgians.

However, this book – and its extensive introduction – sets out to challenge this view for not only did Hassall’ s poetry remain unaligned with wider trends but, at its best, it was ruminative, witty, and conversational and was clearly distinct from those with whom he has been compared. Having worked when young as a lyricist for Ivor Novello, it was his experiences of the Second World War which marked the emergence of a more serious poet, one looking to capture the overwhelming nature of rapidly changing events as well as the more mundane aspects to home-front life in which he was involved.

After the war, Hassall’s verse dealt with its consequences not simply physically through a charting of the emerging shapes of industrial life but also philosophically by acknowledging their small place within the grander sweep of history. His burgeoning Christian faith also provided him with a new, more reflective direction. Equally successful as a literary biographer of Rupert Brooke and Edward Marsh, this new volume seeks to place Hassall back to the front-rank of twentieth century poets and men of letters.

[John Howlett]

*****

John Howlett is a Lecturer in Education at Keele University. As well as publishing on the history of education he is an experienced scholar and editor of nineteenth and twentieth century poetry. Previous works include editions of the poetry of James Reeves (Greenwich Exchange Press), Paul Dehn (Waterloo Press), and Henry Newbolt (Liverpool University Press). He is currently working on a book about forgotten poets of the First Word War.

NB: A copy of Christopher Hassall’s The Dancing Years, Selected Poems

can be purchased from Waterloo Press

*****

Christopher Hassell: Five Poems from The Dancing Years, Selected Poems

from CRISIS (1940)

VI

TO gauge a fever, a thermometer

Is placed below that little limb, the tongue.

With bodies politic, the same: among

States that would summon a practitioner

To track their trouble, diagnosis comes,

Not from the stomach of a city, where

Clever opinions glut the vital Square,

But from the humble in their humble homes.

What symptom of a soaring temperature

Under the tongue of Europe did I find,

When, visiting my aunt in her demure

Victorian drawing-room, I stole behind

Her chair, intrigued with her preoccupation

And spied a tract on Decontamination?

IX

MY wireless fills the little sitting-room

With Verdi’s Requiem. The pekinese,

Whose eyeballs are wet marbles, only sees

Her master adding pipe-smoke to the gloom,

Collapsed like one who’s living in his ears,

Mesmerized by a chair or table. She

As well might listen to the shuffled sea

Or wind, for all the purpose that she hears.

xxxAt such a far remove is man from beast,

This racket in the air’s a work of art

To us; yet we in turn refuse a feast

Could stuff with plenty all our wasted days;

A sort of music the attentive heart

Not only hears distinctly, but obeys.

THE UNSAFE ELM

IT stood alone, slightly expanding toward the earth,

Claiming as much ground as possible

For holding on to in a gale;

Three centuries of weather hoisted skyward,

A local incident of giant magnitude

So gradual that no one saw it happen.

But every Spring the sap went roaring up,

Like sparks up a chimney, kindling buds

Till they broke out all over in green fire—

While most of Bayswater was built up round it.

The game was if you touched it first you were ‘safe’,

So who could believe (having so often in childish pursuit

Felt its rough refuge) when it was officially pronounced

‘Unsafe’? Was it not ‘safe’ to everlasting?

Three hundred summers were harmlessly recalling

Vague memories of when the land was mostly water,

As with opprobrious tools they got down to the job,

Broke off at five, came back next day, nor guessed

Their business was the demolition of a sanctuary.

Ropes taut, everyone standing clear,

A crackle like gorse on fire,

An upright shadow’s ninepin-like collapse

(Goliath toppling forward in full armour)

A thud, the ground gives like a rotten floor,

And suddenly there’s much more sky.

From countless gradually expiring twigs there fades

The lingering, slight feel of claws.

Hunched like a toy, here sat the vigilant

Occasional owl, frigidly basking on the bough,

Moon-bathing. Here the frequent sparrow

Paused on its brief, spasmodic, darting journeys.

This levelled patch, struck dumb, vacated,

After that spate of towering rhetoric

Can barely murmur grass,

Seeming to mark the spot where something huge

Heeled over and sank.

Its absence rustles with a noise of water,

Looms at full height. Converging once again

To build their nests of woven wind, the rooks

Amaze with their remembered cries,

Brood overhead, a phantom colony

Asway in space, hatch eggs of speckled air,

While boys, grown old and wrinkled, still pursued

Down labyrinths of failure, rush to it in sleep.

HOELDERLIN AMONG THE STATUES

WHOSE hopes are perished and blown away

And the last shrine of his belief

Cracked, desecrated, overthrown,

What can he think to find

Set up to hail him on his journey

By any road or fountain?

At some exhausted sunrise, mist all around him,

He may lose his path,

Stumble against a nameless pedestal,

Feel round with desperate hands,

Find two stone feet and cling there weeping

Nor even know what unseen deity

Confronts the tenebrous whiteness with superb

Unwavering regard. He can expect

Small comfort else.

Not so with Hoelderlin who made his way

On foot from Bordeaux where the Furies found him,

And arrived at Blois, his road mistaken,

Broke out of the brushwood where a great house

Stood gazing down a mile of planted elms;

And from an upper window they espied him,

A trespasser gesticulating among the statues,

Going from one to the other, for each a word of greeting,

Where round the basin of a silent fountain,

Facing all ways, they stood, holding their stone-cold gestures,

The demi-gods of Greece whom he adored,

And in the centre, one more giant than the rest,

A replica with hyacinthine beard,

His trident broken.

For all the years of madness that came after

This was a fortunate man.

How many claim to have found

The trusting spirit suddenly come home,

Reassured, sent on its way

Rejoicing? We live, bewildered to the end,

Among ambiguous shadows.

Yet always there’s a hope—

Let them only revive, the dead beliefs,

And who knows but one day we may find them,

Each with his emblem and tranquil weathered face,

Naked or with heavy mantles loopt at the shoulder,

Magnificent and upright in the morning brightness,

Standing in silence round our silent fountains.

LANDSCAPE WITH DRAGON

Woodsmoke, or river mist, greying the grey gorge,

Almost as grey as the stream winding among the pines.

Foreground, at left, the usual hermit with pitcher,

As much a part of this as any other legend,

Stooping at the well,

Not, presumably, troubled with dragons.

On the farther side and halfway up the ravine,

Andromeda, an inconspicuous figure,

Naked, secured with chains.

Crouched within sniffing distance,

Mouth open like an ornamental incense burner,

The dragon, registering malice while the victim once again

Gets ready to be mauled.

Top right, at speed, but still a long way off,

Small as a maybug in the buzzing dusk,

The Hero flying in to finish off the story.

Her face is turned away.

She does not see deliverance approaching.

And now, the deed accomplished, she stands erect,

Veiled in her chestnut hair, at liberty,

Till the next dragon.

from BELL HARRY AND OTHER POEMS (1963)

16

In characters still weeping Latin tears

Catullus mourned; Spenser, most musical,

Sang Mutabilitie to mortal ears;

Roses have died in many a madrigal;

Countless the forms in which it reappears,

The monstrous platitude of passing time;

The news is stale by half a million years.

Yet still confounded, rushing into rhyme

As if there were some prodigy to tell,

We sound the alarm, without the least distress

At the redundancy, the waste of wit.

Man suffers, and cries out. Only too well

He knows the way of transitoriness,

But all the same, he can’t get over it.

21

In search of something to be pleased about

– A trifle would suffice – I came upon

The very thing, as I was looking out,

From a shut window at the rods of rain.

The moorhen, which I could have sworn had gone

For good, is back on the old moat again,

Plumply, essentially itself, and bold

To inspect the near bank, nodding in the cold.

Welcome, dark tuffet, ball of unconcern,

Oblivious of me, faithful to return,

Inscrutable, familiar, alien still,

Taking such gifts as Nature may afford,

Running strange errands for an absent lord

Or principle of life or what you will.

*****