******

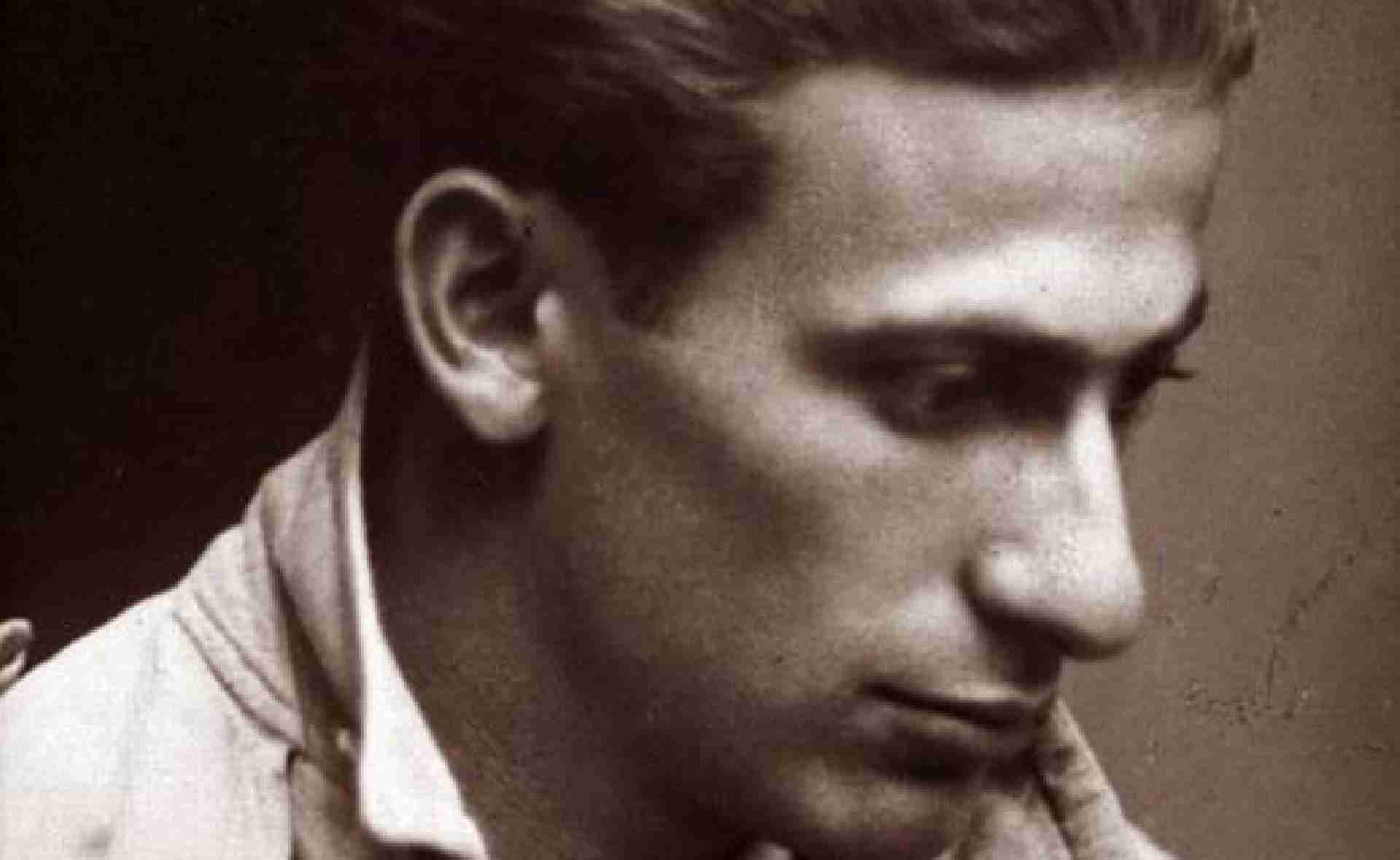

Miklós Radnóti was born in 1909 into a Jewish family in Budapest. After graduating from Szeged University he supported himself as a private tutor and translator. Among the poems he translated were those of the Roman poet Virgil. Although by the early 1940s he was achieving recognition as one of the leading young poets writing in Hungarian, in the course of the Second World War he was compelled to serve several terms of forced labour. He was executed during a forced march in 1944.

*****

SECOND ECLOGUE

The Pilot

We came by night and I laughed with malevolent glee

As the fighters swarmed all around us like angry bees.

The resistance was fierce—but at last our squadron appeared

Above the horizon. And yet, there were times when I feared

They’d pick us all off and clear us out of the skies;

Well, now I’ve returned! And tomorrow Europe will hide

Like a coward in darkened cellars, shaking with fear…

But tell me: have you been writing since last I was here?

The Poet

What choice do I have? Poets write poems and cats

Miaow, dogs howl and fish lay their eggs, since that

Is what they must do. And I’ll faithfully write it all down,

So you’ll know up there what it’s like down here on the ground

When the light of the blood-stained moon seems to waver and fall

In the midst of a chaos of streets and collapsing walls,

When everything crumbles and terror fills all the squares,

When the earth stops breathing, the very sky despairs

—But the planes keep coming, departing, then coming again,

Assailing the helpless world like a crazy refrain.

I write, for I have no choice. And I wish I could show

All the risks involved in a line of verse, so you’d know

This, too, is a kind of courage: a poet writes poems,

A cat miaows, a fish lays its eggs, and so on

And so forth. But what about you? You don’t know a thing!

You attend to your plane, and your ears begin to ring.

Admit it: you’ve grown to be part of that aircraft you fly.

But what do you think of, alone up there in the sky?

The Pilot

Laugh if you like, but what I feel most is dread;

I long for my darling, to lie down there in my bed,

Or simply to sit, humming a tune about her

In the din of the pilot’s mess. Yes, when I’m up here

I dream of the earth; but on earth I long to take flight

Once more from an alien world. And, of course, you’re right,

Perhaps this machine and I have become too close,

For the same cold rhythm of fear unites us both…

But you’ll write all this down! And then men will know that I

Was a man like them—though now, between earth and sky,

I’m a homeless destroyer. But who’ll understand me until

You write it all down?

The Poet

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxIf my life is spared, I will.

27 April 1941

***

CHILDHOOD

The Indian, motionless, pressed himself close to the ground

As anxiety swept through the trees with a hissing sound.

The scent of gunpowder drifted still on the breeze,

Two drops of blood gleamed on a cluster of leaves.

On a tree-trunk a dizzy beetle performed gymnastics;

The dusk was as dark, like the Redskin. And death was heroic.

25 January 1944

***

THE ROOT

A current of strength slides through the root;

It drinks the rain, it feeds and grows

In the earth, its dreams are as white as snow.

From earth to earth the root aspires;

Stealthily, slyly it creeps along;

The limbs of the root are supple and strong.

In the limbs of the root the worm is asleep,

In the foot of the root it silently turns;

All the world is infested with worms.

But the root goes on living down below,

Caring for nothing in all the world

But the leaves on the branch which rustle and swirl.

The branch is what the root admires

And nurtures; it send it delicious flavours,

All kinds of sweet and heavenly savours.

Now I myself am a root as well;

I live surrounded by vermin, too,

Where I try to complete this poem for you.

A flower once, now a root instead,

I feel the earth pressing down on my head;

My life has reached the end of the line;

Above me the saw is beginning to whine.

Lager Heidenau in the hills above Žagubica

8 August 1944

***

SEVENTH ECLOGUE

Look, it grows dark and the floating barracks, surrounded

By oak trees, hemmed in by barbed wire, succumbs to the night.

Slowly the gaze releases our framed captivity

And only the mind knows how tightly the wires grip.

Do you see, dear friend, the way in which fantasy frees itself,

As easeful sleep dissolves our broken bodies

And once again the prison-camp turns towards home.

Ragged, with shaven heads, snoring, the prisoners

Fly back to their distant homes from Serbia’s dark summit.

Their distant homes! But does home still exist or has it

Been struck by some bomb, perhaps—is it still as it was

On the day we signed up? The one who groans on my left,

The one who sprawls on my right—have they made it back home?

Say, do they still have a home where these lines will make sense?

Feeling my way, line beneath line, without accents,

In the darkness, I write these verses the way that I live,

Blindly, inching my way like a silkworm across

The paper. Pocket-lamp, notebook—they’ve all been taken

Away by the lager’s guards, the post no longer

Arrives and nothing but mist descend on our barracks.

Poles, Frenchmen, noisy Italians, dissident

Serbs and wistful Jews live up here in the hills

Among rumours and vermin, their bodies broken and feverish

—And yet it’s one life they live, as they wait for good news,

A word from the woman they love, from a free human being,

And long for release, for the miracle lost in the dark.

I lie on a plank, among vermin, caged like an animal

As the fleas lay siege, but the flies at least have relented.

It’s night and, see, my sentence is one day shorter,

And so is my life. The camp is asleep and the moon

Shines on the world and the wires still bind us tight.

I look through the window and see the sentinels’ shadows

Patrolling a wall amid noises that drift through the night.

Do you see, dear friend, the camp is asleep and dreams

Are swirling around me as someone wakes up with a start,

Turns on his narrow bed and then drifts back to sleep,

His face lit up by a smile. Only I sit awake,

The stub of a spent cigarette in my mouth instead

Of the taste of your kisses and sleep still shuns me because

I neither know how to die, nor to live without you.

Lager Heidenau, in the hills above Žagubica,

July 1944

Stephen Capus has published poems, translations and articles in a variety of magazines, including Acumen, Agenda, Modern Poetry in Translation, Orbis, Shearsman and Stand. His translations have appeared in the Penguin Book of Russian Poetry (Penguin 2015) and Centres of Cataclysm (Bloodaxe 2016). His pamphlet 24 Hours was published by Rack Press in 2020.