*****

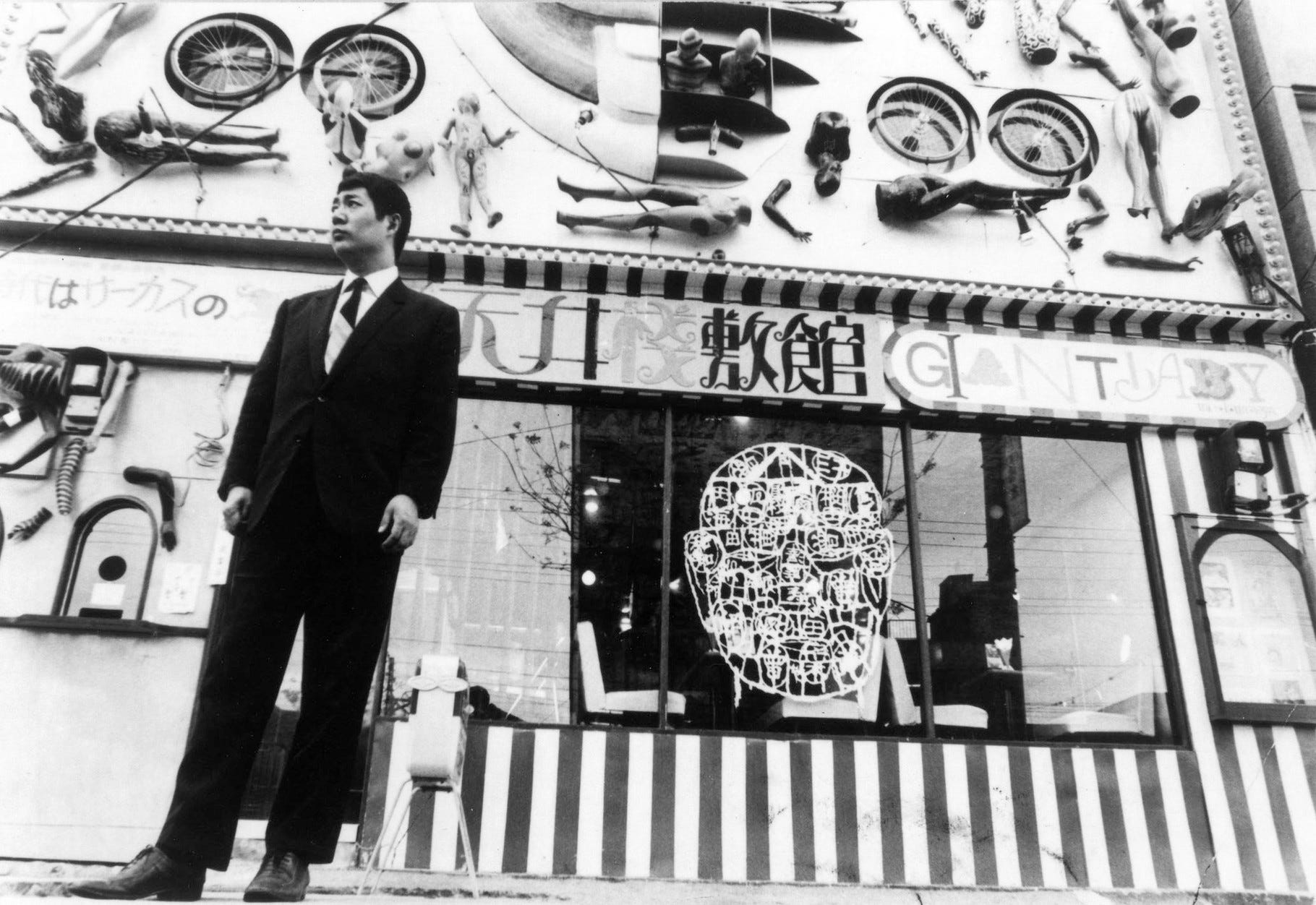

Terayama Shūji was one of the most prolific ‘outlaw’ writers in the 1960s and 70s in Japan. His work is well known domestically, but unfortunately he remains virtually unknown outside of Japan, except among specialists. Terayama wrote poetry, essays, novels, short stories, film scripts, and plays, and made short and full-length films, as well. As an iconoclast and agitator, he was frequently on the fringe of the literati expressing counter-culture, revolutionary ideas about social behavior, sexuality and philosophy.

*****

Elizabeth Armstrong has taught Japanese Language at Bucknell University for the past 25 years . In addition to teaching all levels of Japanese language and teaching Terayama in the advanced classes, she also teaches courses on Translation Studies. She offers this translation for publication as a rendering of the original which will transmit Terayama’s voice in a poetic, but not necessarily flowing text. I find it important that the reader be aware that this is a foreign text through the reading experience.

*****

Introduction

I have translated Terayama Shūji’s poetry collection, Terayama Shūji shōjo shishū, (寺山修司少女詩集, KADOKAWA) to which I have given the provisional English title, Terayama Shūji Girls’ Poetry. It was published in Japan in 1981, and comprises more than 250 poems of various lengths and forms. Despite the title’s charming title, the poems address such themes as love, loneliness, grief and memory. There are nine sections each treating a different theme.

Some poems are linked, others stand alone. A cluster of poems might be characterized as stream of consciousness, and yet others are prose poems that present more like essays. Throughout the book, there are several threads that bind the poems together: love lost and love found, death, astronomy, abuse and bereavement to name a few. Terayama also revels in word play, oblique reference, sentences or words written backward, calligrams, omission of punctuation, or use of punctuation that is of his own creation. This, as one might imagine sets the bar exceedingly high for any translator tasked with rendering the unrenderable. The last poem I offer here is a good exemplar of the unrenderable due to the euphony, homophonic wordplay and Japanese character usage.

One of Terayama’s closest friends and associates in the Japanese publishing industry claims Terayama, one of the most renown multi-genre writers of his day, was relegated to the periphery of the literary world largely because he rejected conformity and did not curry favor in the appropriate places. His work was experimental, contrary and revolutionary, generated in nearly all forms of media. His talents were respected, but not embraced as those, for example, of Murakami Haruki. Perhaps even now, some of his more prominent works are considered too avant-garde for a general audience in Japanese or in English. Terayama Shūji’s Girls’ Poetry presents Terayama highly associative mind, penchant for wordplay and sharp rhetoric, as well as a more tender and vulnerable aspect

of his personality

I have translated two other Terayama works: The Crimson Thread of Abandon (MerwinAsia, 2013): a collection of Terayama’s short stories; and When I Was a Wolf (Kurodahan Press, 2016) a collection of fairy tale rewrites. The third work I have translated, In Praise of Transgression, is currently under peer review. Should this poetry collection be published, that would bring the number of his works in English translation to four. Given his importance in contemporary Japanese literature, and the fact that we have just passed the 40th anniversary of his death, bringing more of his writing to an English-speaking audience would move him one more step toward his rightful place in literary history.

Fans of avant-garde and experimental literature will enjoy these poems. As far as I know there are no comparable works already published in English; however, I would venture to say that Ōe Kenzaburo’s early work is not dissimilar to Terayama’s. Both consider themselves navigators of a “marginal world.” Terayama, however, is more and extreme in his thinking and use of language. [EA]

*****

The editor would like to express his gratitude to KADOKAWA CORPORATION, the Japanese company which holds the rights to the original in Japanese, for permisssion to publish these poems. {Ed]

Terayama Shūji: Eight Poems translated by Elizabeth Armstrong

THE TEMPTATION OF ORCHIDS

Among all flowers, orchids have more mystifying organs hidden beneath the soil than

anything that appears above ground. These take on a mysterious egg-like shape which

Rabelais referred to as ‘testicles.’ In flower language orchids are all associated with death

in some way; and though they are sinister, they are unsurpassed in their floral beauty and

opulence. That said, I detest orchids not because of their superficial aspect, but because

they share a name with a woman who betrayed me.

Orchid had the presence of a perpetually hung-over countess. She toyed with me at a time

when I had just begun to write poems.

I was at her house one evening tutoring her daughter in science, when she called out to me

from the pool. ‘Come see the flowers floating in the pool!’ Orchid was swimming about,

frolicing like a young girl.

And she had not a stitch on, to boot.

NOVEMBER RECOLLECTIONS

November when I watched the smoke

November when I said farewell

November when I stood in the bookstore

reading a book on child rearing

November when we had make-up

sex all night long

November when I got caught in the rain on the way to the realtor’s

November when I bought a guitar and brought it home

November when I saw an article in the newspaper about suicide

November when a nameless flower bloomed

November when we posed riddles to each other

November when I bought a new hand bag

We encountered each other for the first time in November

We parted in November as well

In November the town was immersed in sea fog

THE WORLD

I get up from the table

I go to close the door

A shrike is calling outside the door

Outside the door the bitter autumn wind blows

I return to the table

The oil heater illuminates my face

I open up the newspaper

The bathwater heats up

We are silent

It is October

A woman who is close to becoming a mother

winds the Earth in yarn

like human history

And all day long

Does not move from her chair

THAT I MAY REMEMBER

I want to forget all about

the old organ grinder

on the banks of the Seine

I want to forget all about

our first kiss

shared in the fields of green wheat

I want to forget all about

the trip I wanted to take

and the four-leaf clover

I had stuck in my passport

I want to forget all about

the morning light

that shone through the curtains

in the Amsterdam hotel

I want to forget all about

you because you were

my first love

I want to forget that I may

remember all of this

in an instant

CONTEMPT FOR COSMOS

Cosmos ……… An old-fashioned country girl

Cosmos ……… The child who comes late for Beyer’s elementary piano practice pieces

Cosmos ……… The flower that waits for hours in a corner of the playing field not realizing

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxthat it was being made a fool of

Cosmos ……… A mimeograph of a yet unread poetry collection on life’s home dispensary

Cosmos ……… The bookmark in an incarcerated old woman’s diary

Cosmos ……… A handmaid for whom lipstick is unbecoming

All this said, don’t you think that me writing this is a little over the top for a flower hating

xxxflower admirer?

What I have written is nothing but lies.

Despite the fact that I love flowers beyond imagining, the truth of the matter is that when

xxxI lay eyes on them, I am involuntarily tempted by evil intentions.

A LIPSTICK CALLED UNHAPPINESS

1

One day two lipsticks were sold at Mr. Burro’s cosmetics shop in the back alley.

One was purchased by a regular lady customer who always bought the same kind, and the other was purchased by a freckled girl who did not even look fifteen.

This story is about the second lipstick.

So, go ahead and pour some coffee out of the coffee pot into your cup. Put in one sugar and stir. Now go on to the next line.

2

The freckled girl looked in the mirror.

A moon with full lips was reflected there.

The girl put lipstick on for the first time in her life.

(Why did she put on lipstick?)

(Because she was going to meet a boy.)

(Did she think they were going to kiss?)

(Perhaps.)

(Is lipstick necessary for a kiss?)

(Well, yeah. My lips are not very tasty.)

The girl’s lips

had not yet ever whistled even once in her life

had not yet ever been pressed up against a pane of glass

had not yet ever held a flower

and of course

had not yet ever been kissed

3

The girl was to meet the boy in the hold of a ship that was docked in the harbor

The boy was a sailor in training

The boy had a tattoo of lips on his arm

(I suspect those lips belonged to his first sexual partner

It was probably the lipstick mark from the Malpelo Island Consulate women he had tattooed on his arm)

The boy took the girl in his arms

as if he had been lying in wait

The girl closed her eyes

But, instead of kissing her

he abruptly attempted to tear off her skirt

The girl, shocked as she was, roughly pushed him away

(though she probably didn’t intend to do so)

The boy, pushed off balance, tumbled back and hit his head hard on the bottom of the boat

You bitch! he cried

The girl shouted, I hate you, and ran away

She hear a door slam behind her

Bang! Bang!

Here, let us pause for a moment for a sip of coffee.

Let me tell you a fascinating story about lipstick.

The people of ancient times thought that evil spirits entered the body through the mouth.

In order to prevent entry through the mouth, they hit upon the idea of painting the color most loathed by evil spirits around the mouth (in essence, on the lips). (That was crimson.)

That is the origin story of lipstick for you.

And now, please continue reading the story.

4

The girl wondered why the boy didn’t kiss her

and she began to think that maybe it was because of her lipstick

It was then that she threw her precious lipstick (only used once) into the river

5

The one who picked up that lipstick was an elderly queer

He had decided to live in his dead wife’s image

and so Johnny, the destitute queer standing on the street corner dressed up

xxxas his dead wife

picked up the lipstick and danced a jig, delighted to see that it was new

Maintenant que la jeunesse

Suit un nuage étranger

ARAGON

I haven’t been able to buy lipstick for such a long time, whispered Johnny

He turned to the mirror and carefully began to apply makeup

He was lovely

(I’m the spitting image of my dead wife) thought Johnny

In his Sunday best and in fine fettle he set out for town waving all the way

He was so taken with his own beauty that he did not notice

the hearse coming toward him

And in an instant, he was struck

and died just as his beautiful wife had

And on the street lay a lipstick that had only been used twice

6

The person who picked up that lipstick was Madeleine, the female pianist who was giving her first recital that night

Oh, how pretty! she said as she took it in her hand

But I can’t continue to write this tale

It is a cruel saga

You see, the lipstick was “the lipstick called unhappiness”

Now, please turn the page and drink your coffee before it gets cold

There isn’t even a one in a million chance that a lipstick like this exists

There is always a happy life waiting in the wings after a tale of despair

GIFT

I sold a memory

and bought one jewel

To buy back that memory

I sold the jewel

To buy back the jewel

I sold a memory again

It gradually became more worn and soiled

Between the love in the memory

and the jewel which took on a new luster

the girl stood absentmindedly

This is all before life

teaches her about grief

ACCESS (1)

A sole musician

wanted to score a piece for

the sound of the sea

The musician had never heard a symphony of

that magnificence anywhere

But the musician was

too ill-equipped to write

it down on manuscript paper

From the moment he set down

the first note

the manuscript was drenched

He was showered with spray

He closed his eyes, gritted his teeth

and barely kept himself

from drowning to death in his own dream.

He was not at all convinced

that he had scored anything at all.

Back to the top