*****

Tara Bergin: Savage Tales • D A Prince: The Bigger Picture • Jules Whiting: Folding Time • Maeve McKenna: A Dedication to Drowning • Michael Daniels: Ravenser Odd • R.A. White: A Frame Less Perfect

*****

Tara Bergin’s Savage Tales reviewed by Pam Thompson

Savage Tales by Tara Bergin. £15.99. Carcanet. ISBN: 9781800172319

Tara Bergin was born and brought up in Dublin, near to where Samuel Beckett was brought up. She currently lives in Yorkshire, is an academic at Newcastle University. Her PhD research centred on Ted Hughes’s translations of Hungarian poet, János Pilinszky.

Beckettian dark humour and seeming absurdity colours earlier collections, This is Yarrow (2013) and The Tragic Death of Eleanor Marx (2017), and spill over into this Savage Tales. Bergin’s sources are eclectic and numerous, her first two collections containing extensive notes on the poems. There is a preoccupation with characters, different voices and literary forms such as folklore, fairy-tale, dream, theatrical monologue and a slant approach to the lyric.

This latest collection is over 200 pages long. The poems are mostly short, some, a single sentence, and include aphorisms, short dialogues, and found text. They are different from Bergin’s previous work – I was reminded, at times, of Anne Carson – but they distil previous preoccupations and so, with that certain tone, are recognisable as hers. The title of each poem is placed at the foot of each page allowing the reader’s eye to roam the white space underneath the poem before considering its title. This is how we might approach a painting, looking at the art first, and the caption later, then going back and forth to let one ‘reading’ inform the other. There are nine sections: each section’s title gives a broad indication of its content and/or approach: I. The Artist and His[sic] Work, II. Campus Poems, III. The New Romantics, IV. Strange News V. The Sleep and Dream Notebooks, VI. Wolf Fables, VII. The Blackbird Diaries, VIII. Four Dances and IX. Constructions.

The title of the first section, ‘The Artist and His [sic] Work’, is a dig at thoughtless gender stereotyping with play on the reading and spoken implications of ‘sic’/’sick’. ‘Artist’, covers writers and visual artists, or – mostly males – who are both:

Oh Rose, I said to myself as I unlocked my bike, Thou

art sick. Then I rode into the stinking traffic feeling

comparatively cheerful. xxxxxxxxxx‘Blake’s Rose’

There are poems which appear as parts of a running-joke about writers:

We get a lot of writers in here, said the optician tightening

the screws. xxxxxxxxxx‘The Optician’

We get a lot of writers in here, said the rollercoaster operator

lowering the bar. xxxxxxxxxx’‘‘The Rollercoaster Operator’

Tara Bergin’s comments at her online launch (the video can be found on YouTube) are helpful in understanding her process. She had been writing in different forms (e.g. essay, play, novel) and had a lot of material but experienced a kind of crisis, which she referred to as ‘a loss of voice’, in relation to new work. In the end she decided to sift and cut down, to let ‘a strange flat voice’ take over. The resulting short pieces were unlike anything she had written before. She decided that they were poems and that the voice itself had become something of ‘a character’. The poems drew on everything that was going on in her head at the time, including ‘non-sequiturs and social misfiring’. In fact, an amount social withdrawal proved crucial for the development of this work.

Why place titles after the poems, at the foot of the page? Bergin hoped that the title would let the reader ‘turn back’ and consider the poem in its retrospective light. Ideally, it would ‘unlock’ the poem. I found that sometimes the poems the titles re-stated the poem’s subject in a dead-pan way (as in the last two examples above) or added another dimension as in these two examples from ‘Campus Poems (II)’ which Bergin dedicates to everyone in classrooms, especially at her university.

When William Carlos Williams said ‘don’t blush to write a

poem’ did he mean we should open up or close down? xxxxxxxxxx‘Blushing to Write This’

There is always the double-edged worry that we are missing

something of significance or over-interpreting what we see. xxxxxxxxxx‘The Sword’

Having taught in a university, these poems speak to me of the public performance that is teaching; how sometimes your mouth takes over from your brain – not always in a bad way –and you never quite know what will come out. ‘The New Romantics (III)’ evokes the 1980s, and, I’m guessing, Bergin’s adolescence, with allusion to its music and fashions. There is deliberate melodrama and wit about love and various encounters:

The seduction: If I fall in love with you I’ll kill myself. xxxxxxxxxx‘Success’

My favourite:

Romantic: I wandered lonely.

New Romantic: I only want to see you dancing in the purple

rain. xxxxxxxxxx‘Let Me Guide You’

In ‘Strange News (IV)’, situations in everyday life acquire a kind of oddness; the heightened imagery and disjointedness of actual thought, which too can be very mundane.

Savagery in the fields again: the white flesh of the hawthorns

torn and exposed; limbs strewn at their feet. xxxxxxxxxx‘Field Notes’

Tsvetaeva: I’m so and so, the wife of my husband and the

mother of my children. xxxxxxxxxx‘October 1917’

The ‘tales’, with their various moves towards personal and public displacement, have the feel and structure of dreams which arrive in fragments, juxtaposing people and incidents from various times in the dreaming person’s life. They seem to inhabit a hypnagogic state, between sleep and waking, or other state of altered consciousness. In ‘The Sleep and Dream Notebooks (V)’ a spotlight is thrown directly on night, sleep and not sleeping, dreams and hauntings, in contrasting ways:

You are the quail in the mouth of night. xxxxxxxxxx‘Night Feeding’

Dream: The butcher kisses me on the lips and takes me by

surprise. Reality: He stands among the carcasses which are

bone and flesh. xxxxxxxxxx‘Dream vs Reality’

Wolves in folklore have positive and negative traits: loyalty and independence; greed and savagery. One of Freud’s most famous patients was Sergei Pankejeff , the so-called ‘Wolf Man’, whose dream of wolves sitting in a tree preceded a period of considerable anxiety. Undercurrents of anxiety and violence are threaded through ‘Wolf Tales (VI)’:

Little Red Cap: Oh my God, how frightened I am today. xxxxxxxxxx‘Fairy Tale’

And a comeuppance which ends badly in a longer tale where sheep steal the wolf’s eyes while he was sleeping “and stuck them onto his back legs”, concluding:

In the morning the wolf killed the sheep as usual.

But for once he saw the damage he had done in hindsight. xxxxxxxxxx‘Wolf and Eyes’

‘The Blackbird Diaries (VII)’ has a more elegiac tone relating to memories, ageing, identity and the past in the present. I think these poems also directly refer to lockdown, to sickness, death and a renewed attention to nature. A springboard influence is Wallace Stevens – not only his ‘Thirteen Ways of looking at a Blackbird’, but his first collection, Harmonium, which is hidden in plain sight in the first poem:

This could change my whole life I thought when I heard the

first few notes of the harmonium. xxxxxxxxxx‘Overreaction’

I used to listen to the news in the morning but now I listen

to the blackbird. xxxxxxxxxx‘The Messages’

The speaker thinks of her mother and sees herself in the mirror as resembling her.

Today the oval mirror is covered by a black cloth. It’s not for

mourning; it’s the washing hanging up to dry. Either way it’s

a relief not to see that grey-haired woman every time I go up

the stairs. xxxxxxxxxx‘The Burden of the Mirror’

The uneasy humour disguises troubled thoughts of seeing signs of ageing, and about hauntings, how we haunt ourselves, or how our selves become so permeable that we allow others to crowd in, be it relatives or other writers. It’s good to see ekphrastic poetry broaden to encompass art forms other than the visual ‘Four Dances (VIII)’ is the shortest section comprising four ekphrastic prose poems each titled with the name of a dance; ekphrastic because they respond to scenes in the film Pina by Wim Wenders, about experimental dancer and choreographer, Pina Bausch. Bergin refers to them as ‘transcriptions’ and each creates a compelling world:

First my right hand opened through my left hand. Then my

Right hand touched my forehead. Then my right hand fell

downwards like a leaf. Then I made two fists and held them

up in the air. Now I have lived a whole life. xxxxxxxxxx‘The Seasons Dance’

Bergin’s interest in translation is inextricably linked with her poetry. Arguably, ekprastic poems – ideally those which do more than just ‘describe’ a painting etc. – are ‘translations’ from one art form to another. Here, and in the final section, ‘Constructions (IX)’ I was reminded of New York School poet, Barbara Guest, whose Collected Poems experiment with form and the intersections between art and poetry, spatially and sonically. The poems in Savage Tales contain the essence of previous collections but there is a radical shift in overall tone and style, and in the ways in which we are asked to read them. If the poems were paintings they would be Paula Rego/Dorothea Tanning hybrids. The effect of the poetry is cumulative, hypnotic; it demands several re-readings. I look forward to what Tara Bergin has in store for her next collection.

Pam Thompson is a writer, educator and reviewer based in Leicester. She has been widely published in magazines including Atrium, Butcher’s Dog, Finished Creatures,The Alchemy Spoon, The High Window, Ink, Sweat&Tears, The North, The Rialto, Magma and Mslexia. Her works include include The Japan Quiz (Redbeck Press, 2009) and Show Date and Time, (Smith|Doorstop, 2006). Pam’s collection, Strange Fashion, was published by Pindrop Press in 2017. She is a Hawthornden Fellow.

*****

D A Prince’s The Bigger Picture reviewed by Alwyn Marriage

The Bigger Picture by D A Prince. Happenstance Press, 2022. ISBN 978-1-910131-70-1.

The Bigger Picture is Prince’s third full collection and it presents a pleasingly substantial body of work. Poets sometimes choose to select poems for a collection around a clear theme, and this can, obviously, work well and be satisfying; but others offer an eclectic range of subjects and, as in this new collection by D A Prince, this can also be both fascinating and refreshing. So it is that to travel through The Bigger Picture is to find oneself constantly focusing on new areas of life and experience.

A few of the early poems in the book refer back to Prince’s schooldays, recalling an era in which learning history was, partly, the imbibing of xenophobic attitudes:

We learned. They were foreign,

dark deeded, defined by dates,

coughing up vowels stinking of garlic,

dead in their plots of obfuscation.

…

They were not, we learned,

like us.

Never like us.

‘One side of history’ (page 15).

Themes do, however, emerge. Travel, for instance, is celebrated in several poems, including the charming engagement with Proust in ‘Billet à Composter’: ‘… that’s the church, / the gate Swann used, Tante Leonie’s, / the baker selling madeleines.’

International films, too, make an appearance, including the Italian film, ‘l’éclisse’ and the Polish ‘Shot in Academy Ratio’. I have not seen either of these films – indeed had not heard of them before – but the poems are so evocative that I almost feel as though I have watched them.

Several of the poems refer to art, in particular ‘Students in the Courtauld’, ‘Iggy Pop Life Class, 2016’ and ‘The House of Cards’ (Chardin). And there is a very successful evocation of a scratched Leonard Cohen vinyl record, in ‘If I’ve got to Remember’:

it’s cut into the track,

crac-crac, this version, ours (or mine)

imperfect, pressed and circling,

static crackling like a distant storm.

(page 59).

Not so much a theme as a recurring motif, is silence, to which the poet is clearly attracted and to which she returns a number of times in memorable phrases. In ‘Illegal’, for instance (page 17), she refers to ‘the pause / before snapping the padlock of silence’; in the poem actually entitled ‘Silence’ (page 22) we have ‘that crystalline glitter of quartz / veined in the rock, the way a collar / of water waits in yesterday’s hoofprint’; in ‘The painter of icons’ there is ‘while brushes wait / cleanly, in a sheen of silence’ (page 60); and in ‘No worse’ on page 33, in which the poet tantalisingly presents us with hints of a half-told story, she begins each verse with the word ‘silence’.

I also wonder whether part of the attraction of the wind farm described in ‘Visibility’ on page 10, is the silent power it represents:

Their arms are siren-welcome, with an unheard song

that in some lights rings like a summer shower

on shingle, clean as a rinsed moon.

So there are plenty of themes; but for me, one of the most enjoyable features of this collection is the way the poet engages with other, earlier poets, letting their work bring a reflective gleam to her own poems and sometimes almost flirting with those other well-known works without ever lapsing into the derivative. Some are obvious: ‘the traveller who could still / knock on the moonlit door’ (page 17), while others, such as ‘The stolen shadow’, with its echoes of Eliot, are more subtle. Examples include Robert Frost, W H Auden, Edward Lear, T S Eliot and Philip Larkin, – the last of these, ‘Petition’, playfully echoing Larkin’s ‘Born Yesterday’, but instead of addressing a new-born girl, the poet here addresses the new day:

Let today be ordinary. Just

quiet. Sky unmemorably grey.

Nothing red -letter. …

… Let its business be nothing more

than breath and listening to the fridge

humming the leftovers to sleep,

the clock moving on the minutes.

(page 63)

Some poems address our experience of lockdown, such as ‘Into April’, on page 46 which recalls ‘This month / released from chains of vapour trails’; and several poems celebrate the unexciting and ordinary, such as ‘Rock Pipit’, (page 49) and ‘The Knife’ (page 53):

… he gave the blade

an edge that’s never dulled, that’s always keen

to slice a windfall apple or dig round

a wound gouged dark in the potato’s side.

Among the other delights in The Bigger Picture is the minute observation with which the poet illuminates small details, such as the modest wood sorrel, celebrated in ‘Homesick’: ‘its shy whiteness threaded / with purple veins / …. / the green lettering of its leaves, / their creased precision soft as fresh paint’ (page 47).

Throughout this collection, Prince treats us to beautiful sharp descriptions of ordinary things, ensuring that they will never be seen as ordinary again. How perfect, for instance, to experience the dawning of morning light as: ‘Dawn slips a thin knife down the shutter’s edge / straight as a plumb-line, sharp and quickening’ (‘Le vieux port, Marseilles’, page 43). Or, observing accumulated snow: ‘Look! a white cap, five inches high, makes a chef / of the lamp post’ (‘Is your journey really necessary’, page 30). And how many poems are prefaced with a web reference, as is the case with the delightful ‘Distraction’ on page 48?

D A Prince’s last collection, ‘Common Ground’, won the East Midlands Book Award in 2015. I would not be surprised to find The Bigger Picture making the shortlist of awards again this year.

Alwyn Marriage‘s fifteen books include poetry, fiction and non-fiction and she’s widely published in magazines, anthologies and on-line. Her latest books are The Elder Race (fiction), and Pandora’s pandemic and Possibly a pomegranate (both poetry). Formerly a philosophy lecturer and then Chief Executive of two international literacy and literature aid agencies, for the last 15 years she’s been Managing Editor of Oversteps Books. She gives lectures and readings all over Britain and Europe, and in Australia and New Zealand. www.marriages.me.uk/alwyn

*****

Jules Whiting’s Folding Time reviewed by Kathleen McPhilemy

Folding Time by Jules Whiting, £9.00, Vole, Dempsey and Windle, ISBN: 978-1-913329-71-6.

The narrative thread running through this collection is the story of the author’s liver transplant. Awareness of her life-limiting condition helps us to understand the title –

‘folding time… is consciously choosing to invest half the time but expecting twice the results.’ (Neen James. There is a vivid urgency in these poems which celebrate self, family and place in a way which is sometimes stark, but never mawkish or maudlin. The place is the village of Cholsey in Oxfordshire where the poet grew up and which is central to her family. The figure of Grampy Jim, which recurs in the collection, seems partly an alter ego, partly, with his lore and experience, a spirit of place. He gives a countryman’s matter-of-fact advice about death, ‘You don’t go before your time’ and the everyday business of killing and dying:

You get used to the knife’s screech,

the red of his belly,

the sizzle of innards

as they hit the cold ground.

It’s simply a matter of folding

his body into your jute bag,

wiping the blade on your pants,

and, at my signal, move on.

‘Grampy Jim’s Advice

Asrael, the Angel of Death, visits Grampy Jim as, later, he toys with the poet, ‘We play hide and seek’ … ‘How his toes wriggle, / as he whispers, / Here I come, ready or not.’ In ‘Closing the Circle’ we hear of Grampy for the last time. The poem describes a ritual Christmas visit to a family landmark, the ‘top of Ilges’. This year, ‘perhaps my last’, they pass his grave

beeping the horn, calling out to him, Hello Jimmer,

as we take the humpback bridge

over the Bunky line stomach-leaping fast,

laughing, knowing we are nearly home.

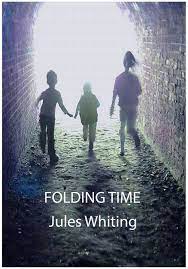

This is typical of Whiting’s poetry in its sense of rootedness and celebration despite all the sorrows and uncertainties. The importance of tradition handed down through family and the feeling of connection to place is perhaps unusual at a time when so much poetry comes from writers who have been uprooted or displaced, although Alison Brackenbury is perhaps closest among contemporary poets. The image of the long tunnel, captured in the brilliant cover photo, appears in the first poem and again in ‘The Path to Amwell Springs’.. At a literal level, it is part of the way to Amwell Springs, ‘sticky mud’, ‘trampled soil’, ‘steady, / steady, this path / is as knotty / as the knuckled spine / of a praying man’, but becomes ‘the long dark tunnel / where shadows sucked down / fill the mud-trodden floor’. It is no accident that the next poem, refers in its first line to a near-death experience. Whiting’s poems often resonate far beyond their literal meaning, but it is because they are so grounded in sharply observed physical detail that the figurative meaning or the implicit thought are so successfully communicated. Some of the most moving moments are where the beauty of the local and everyday is illuminated by the awareness of mortality and pain. I find this in ‘Damaged’ where pruning roses takes on a new significance, ‘You’ve been a while now with the roses, / cutting away excess buds, spoilt flowers. // It’s a job I can’t face, this shortening of life.’ The pain in this opening stanza modulates to acceptance in the last, but still in the context of the domestic environment:

In the wash of light beyond the back door,

butterflies balloon through purple buddleia.

Shadows circle, wait for evening to land.

Most of all, this book is a celebration of love, love which triumphs over sickness and mortality. It is married love, signalled by the presence throughout the book of an unnamed ‘you’, ‘a constant just like you’ in the first poem, or in the memories of the title poem:

Show me how to fold back time,

back to Galicia,

that seafront café –

filled with sea mist and cooking

our fingers dripping

silver-scaled sardines…

The poem ends with a brilliant continuation of the fish imagery to link past and future, as she imagines the post-operative return of her rings, ‘my rings will swim back / across your palm //with the dull gleam of fish.’ Then there is the love of family, passing through the generations, from the memory of Gran taking out Grampy Jim’s suit after his death in ‘Inherited Memories’ to the story of the display cabinet inherited from a grandmother which has ‘travelled with [the poet] // from house to house’. Realistically, the poet recognises that her kids ‘don’t want it.’ And there is the love of place, beautifully expressed, when the poet looks past her own death and back through the English poetic tradition to John Masefield’s Lollingdowns and other Poems,1917. This final poem is again addressed to ‘you’, but instructs the other ‘not to dawdle in a turned-to-dust field / or breathe a past you cannot live’ but rather find the blackberries they used to share, let them ‘stain your lips / linger on your tongue, / and know that we were the string that threaded / these beads of coloured days.’

Jules Whiting’s book deserves to be noticed and widely read. It is painful, realistic, celebratory and joyful. These poems have been crafted with care under pressure and consequently they shine.

Kathleen McPhilemy grew up in Belfast but now lives in Oxford. She has published four collections of poetry, the most recent being Back Country, Littoral Press, 2022. She also hosts a poetry podcast magazine, Poetry Worth Hearing.

*****

PAMPHLETS

*****

Maeve McKenna’s A Dedication to Drowning reviewed by J.S.Watts

A Dedication to Drowning by Maeve McKenna £6.99. Fly on the Wall Press. ISBN: 9781913211738

A Dedication to Drowning is the debut pamphlet from the Irish poet Maeve McKenna. Her individual poems have been published in a range of magazines and journals and feature as part of a published poetry collaboration with three other poets, How Bright the Wings Drive Us, that won the Dreich Alliance Competition. A Dedication to Drowning is her first solo poetry publication.

The pamphlet contains thirty-three pages of poetry and twenty-five poems exploring: ‘the multitudes of womanhood’. This is taut, intense, vibrant poetry that embraces the rawness of everyday living: birth and death, painful memories and childhood experiences, the tensions and torments of family life, small (and not so small) domestic hells. From the opening line of the first poem: ‘Your son is trying to kill you’ this is poetry in the raw. Much of the focus may be on small day issues, but: ‘each day is a birth, and a burial’.

The language and imagery are dense and the poems benefit from multiple readings to allow the meaning to surface, but there is no doubting the immediate visceral impact the language can have, even if its full meaning sometimes takes a little longer to come through.

In the poem: ‘A Recipe for Hunger’, it may not be immediately obvious what the source of the hunger is, but the reader’s: ‘Reactions simmer on the cooker ring” along with those of the poem’s subjects, and most people will have a gut reaction to lines such as:

Crumbs gather like demons

on a chopping board. On the dinner plate, slivers

of dissected flesh mangle around a fork’s teeth,

Domestic acts like eating become battle grounds: ‘the / slurping silence of another meal time.’ Even the simple act of knitting in the poem: ‘Knitting Wounds’ ‘is a duet of needles composing a scar’.

If the humans in these poems are not having an easy time of it, neither are the numerous animals who crawl through the poems as both subjects and poignant images of helpless misery: ‘mutilated crabs upturned’, a dead dog, family members as spiders, ‘mother dogs discard their thinning hair-coats’:

We crawled about, contorted, watching our bodies

be other animals; all rickety bone, matted hair

and little else, while she flounced under

the reflective plume of a French cigarette, cradling

the cat like a new fur coat,

Given the raw emotions exposed in these poems, it is no doubt apposite that the final poem in the pamphlet: ‘Bookmarker’ references the pain that can be buried in the written and published word: ‘Paper cuts gather as a sequence of blades / slicing against my thumb,’ and:

… I match words

with voices of panic, counsel truth to self-truth,

nurse each sound into obscurity, wait

for it to heal, then hurt.

This is poetry that is felt in the reading and is likely to leave its imprint in both the head and the gut.

J.S.Watts is a poet and novelist. Her poetry, short stories and non-fiction appear in diverse publications in Britain, Ireland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and America and have been broadcast on BBC and independent radio. Her published books include: Cats and Other Myths, Songs of Steelyard Sue, Years Ago You Coloured Me, The Submerged Sea, Underword (poetry) and A Darker Moon, Witchlight, Old Light and Elderlight (novels). For more information, see her website https://www.jswatts.co.uk/

*****

Michael Daniels’ Ravenser Odd reviewed by Kathleen McPhilemy

Ravenser Odd by Michael Daniels. £7. Poet’s House Pamphlets. ISBN:978-1-7399748-2-4

This is the sixth pamphlet from Jenny Lewis’s Oxford imprint, the Poet’s House, and it lives

up to its predecessors in the quality of production and of the writing. However, it differs

from those in that it is composed of one long poem or poetic sequence which explores the

appearance and then disappearance, in the Middle Ages, of the land bank and town of

Ravenser Odd at the mouth of the Humber. Although the prefatory note to the poem

acknowledges ‘the cyclical process of deposition and erosion [which caused] islands and

promontories to build up and wash away on the North bank at the mouth of the river

Humber’, these events have been invested with a wealth of historical and metaphysical

significance. Throughout the sequence, we feel that the poet is worrying at his material, as

he tries to work out its meaning, or its meaning for us. In the prologue, he interrogates the

links between past and present: ‘What is it to be held in mind/ by someone else, to dwell as

ghost / or presence there?’ It seems that these ghosts have pushed their way into our

modern-day minds, displacing our own thoughts and dreams. The poet makes the reader

share his concerns by his use of the first-person plural, ‘they make us feel their lost despair’.

This identification with his audience, together with a strong narrative thread, reinforces the

almost bardic quality of the poem where the tale of a historic community is recounted to a

contemporary community of readers.

Yet though the poem borrows some of the garments of previous times, (the gothic ravens, the feudal horror story, even Dante’s terza rima which evolved in the same period that the

poem is set) it is neither old-fashioned nor pastiche, but rather a quest for meaning, made

contemporary by its failure. In the final section, the lives, prayers and language of the lost

people of Ravenser Odd become ‘carrion of human thought’ as they are transformed into

the raucous squawking of the ravens, who pervade the poems and the margins like

malevolent spirits, ‘to scavenge scraps of uttered word, / then spat them back as raucous

noise, disemvowelling all they heard.’

The black humour of this audacious pun reflects an attention to language apparent in earlier

poems where the poet tries to shake out meaning from etymology: Hrafyn’s Eyr; Ravenser;

Raven’s Tongue : /set clacking in the river mouth’. He turns to the history of language in the

search for meaning but resorts to metaphor, ‘clacking in the river mouth,’ to impose his own

sense. All the way through the book we feel the past as both present and absent; the

inhabitants of Ravenser Odd are ghostly yet demand to be remembered, ‘by some form of

ghostly will, // persist, denying how we choose / to represent their mortal acts.’ At the

centre of the sequence is an unavenged wrong, the murder of three children by a feudal

lord, when he pushes them out to sea in a holed boat and in a savagely ironic gesture ‘shook

three pennies from his purse / and dropped one in each tender mouth’. This may be a

reference to the coin offered to Charon or it may have a more recent reference, but it is a

horrific moment in the poem. It dooms the perpetrator, who, having set himself above the

gods, is haunted by guilt, ‘drowned inside a trap gods set / to drag him through the

undertow’. The poem seems to imply that it was the gods who made this happen or at least

cause it to be re-enacted in our dreams:

Gods think in us. We dream of it.

Our dreams are thought in embryo.

The burden of the children’s deaths and all the other lives and histories refuse to remain

buried, rising again to haunt our minds as the cemetery, battered by the tides, gave up its

dead a century after the town’s foundation:

Then, prodded by the ebb and flow

of tides that mimic give and take,

they stirred their empty skulls below

to rouse their sleeping dreams awake.

Daniels brilliantly represents the power of the sea and the bleakness of his scene; he can

create an atmosphere that is chill and uncanny; occasionally, he offers a little hope as in the

bumper catch of The Silver Pit (p.18) and the suggestion of renewal in the process of

deposition and the carrying off of seeds or roots to grow again elsewhere (p.23).However,

the abiding sense of this short collection is of the burden of the dead, the place they take in

our thoughts and dreams, and the demands they make to be given a voice.

*****

R.A. White’s A Frame Less Perfect reviewed by Kathleen McPhilemy

A Frame Less Perfect by R.A. White. £7.50. Shoestring Press. ISBN 978-1-915553-11-9

There is something almost too unassuming about this pamphlet. The cover, which shows a picture frame askew on a backdrop of shingle or a stony beach, is actually very beautiful but demands a second or even third glance. The blurb is also self-deprecatory, describing the pamphlet as touching ‘on experiences that may resonate with readers.’

One poem that resonated with me was ‘The Interlopers’ which recounts the effect of having jackdaws fall down the chimney. I have had my own encounters with jackdaws and have a fondness for their alien, disruptive intelligence which I find reflected in this poem:

bring your wildness screeching to towers of books

fight each window-pane with tooth and claw

bring your darkness to our pastel shades

The poem widens out so that the jackdaws become a metaphor for some unnamed horror in the life of the speaker and ends with an exhortation to a surely dead jackdaw to ‘Get me that blanket to throw over/ your staring eyes / to calm your fears// to cover you in nothingness. There is a degree of reflexivity here which is quite hard to follow. The action has become psychic rather than actual but it is unclear how the bird or whatever the bird represents can shroud itself.

This movement from the literal to the introspective landscape is also seen in the title poem. A description of a view of St Mary’s Church in Hadleigh, Suffolk, which is where the poet lives, echoes a painting of the same scene in a painting by Thomas Gainsborough. At the centre of the poem is an appearing and disappearing lime tree, not in the painting, in the poem and, as we learn in the footnote, no longer there in real life. This short ten-line poem raises all sorts of questions: is the footnote part of the poem? who is the ‘you’ in the last line, ‘without you a frame less perfect’, the lime tree not in the painting, the lime tree no longer existing in real life, or some human ‘you’ important to the poet? There is a strange contrast in the penultimate triplet, between the violence of the constructed form of the Deanery Tower, ‘spiral chimneys skewering the sky’ and the organic gentleness of the tree’s ‘slender crown’. The fact that this is the title poem, placed first in the pamphlet, indicates its importance, but again it is an importance which is not straightforward for the reader.

Sight, or perhaps hindsight, is a recurring theme. In ‘Cyclops at the Minstrel Show’, memories of seeing The Black and White Minstrel Show in the 70s are recognised as ‘Seeing but not seeing.’, an insight triggered, no doubt, by recent history and Black Lives Matter, although I’m not quite sure of the specific relevance of the Cyclops reference. The idea of imperfect or partial vision is picked up in ‘Seeing Ourselves in the Cathedral’ and ‘Reflections’, to become more poignant in what seem to be poems of grief. In ‘Woman as Machine’ and ‘Christmas at the California’, a belated understanding of another is encapsulated in phrases like ‘now I see it’ or ‘then I saw it – that face shaped like yours / sat alone,… /tapping to another tune.’ Perhaps it is not surprising that these two poems are followed by a poem about a funeral, where the grief is patently raw as the description of an eco-sensitive, humanist celebration ends with the words: ‘some things cannot be made happy // However much we try.’

This small collection seems to reflect many different facets of what we might call ‘ordinary life’: love, loss, parenthood, football, the experience of nature, even travelling by train. The poet’s reticence makes it difficult to know when the poems are merely observations as in the beautifully detailed description of ‘Hobby over Lake’, or when they have a deeper significance for the poet or ourselves as seems to be hinted at in the phrase ‘a boundary of sorts’ in ‘Walking in June’. The final poem, ‘As the Curtains Close’, contemplates the end of life for an unidentified ‘you’, perhaps the poet, perhaps a friend or relative, perhaps the reader:

…who are the faces you will see

As the curtains close

Some in the front row still

Some silent at the back

Waving or calling you home.

This sense of closure seems a little hasty in a debut collection from a poet who will surely grow in confidence and strength.

Kathleen McPhilemy grew up in Belfast but now lives in Oxford. She has published four collections of poetry, the most recent being Back Country, Littoral Press, 2022. She also hosts a poetry podcast magazine, Poetry Worth Hearing.

*****

Reblogged this on The Wombwell Rainbow.

LikeLike

Hello

A poet friend of mine recommended your site to me. My question is: do you have to have been published or have a poetry record in order to be accepted on your website?

Best wishes

Marie Papier

LikeLike