*****

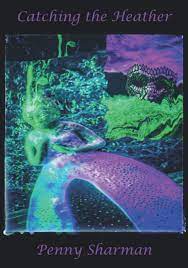

Alexandra Corrin-Tachibana: Sing me down from the dark • Penny Sharman:Catching the Heather • Robin Thomas: The Weather on the Moon

*****

Penny Sharman and Alexandra Corrin-Tachibana

Reviewed Carla Scarano D’Antonio

Catching the Heather by Penny Sharman. £10. Cerasus Poetry. ISBN 97984436600042. Also available to purchase from the author at https://pennysharman.co.uk/

Artistic photography and poetry coalesce in Penny Sharman’s collection. The ephemerality of the heather covering that ground that she catches at certain moments of the year when it stretches its ‘hues across Tame valley’ communicates a sense of resilience and confidence in the power of nature despite the fact that ‘human feet/plunder’ the land. The pictures illustrate the poems in a subtle way, sometimes more directly, at other times adding layers to what is voiced in words. The observation of nature and the presence of birds, flowers and trees are paramount and relevant throughout the collection, together with a constant longing for freedom of space and movement. It is a search for freedom of thought and expression that releases unsuspected strengths. This is a long, troublesome process that Sharman undertakes by exploring sad memories of loss and past traumas:

and those days of laundering the wedding sheets,

as if life was white, not starched grey or black,

and that home wasn’t a prison;

remember when you

chased me around each room with

a knife and my babies seeing and hearing you

like a wild animal;

(‘Wednesday’)

Found on the street:

my heart/in a handkerchief/still bleeding.

(‘Almanac for last Sunday in April’)

However, although what has been lost cannot be restored or replaced, there is a constant attempt to heal in close contact with the environment in an apparent solitude that triggers art and creativity. Animals and plants contribute with their silent presence to this movement of recovery in a dialogue that is fruitful and revealing, as in the poem ‘Vixen at Leiston Abbey’:

You are old like me.

Have we lost our cunning?

Give me your fire-pelt.

[…]

Your gaze shocks me,

says I knew you once

as you silently move

across my curious heart.

The picture associated with the poem captures a moment of alertness, as if the vixen is ready to catch some secrets that, however, cannot be completely unveiled. They remain shadows, as they do in other images present in the collection. Trees are personified too and mourned when they die. Their voice is a ‘melody that rustles,/tree-talk in the air-waves.’ Thus, the poet envisages an encompassing world that comprehends the human and non-human as all joined in a common fragility that makes them real and ephemeral at the same time. The poems suggest that ‘these days of uncertainty’ merge in a creativity that in Sharman is both the art of photography and the practice of poetical language.

Therefore, the imagination might restore the ‘language of love’ in a silent work that creates bonds. As a single mother sent to a mother-and-baby home in 1967 after the birth of her first child, Sharman had to face the stigma of being unmarried and the hardships of raising her three children on her own. This hard experience gave her a profound sense of empathy that she expresses in her poetry, for example in the poem ‘The man with sad eyes’, in which she encounters a man at a café who is buying some cakes for his ‘lost friends and dead lovers.’ The situation seems surreal but then she finds him again at a graveyard with a bouquet of flowers. The final lines express a deep understanding of the man’s feelings and of his bereavement when the poet walks away silently ‘barefoot on wet grass and sharp tree bark.’

The sense of imprisonment and the suffering are therefore eventually overcome by the poet’s desire to widen her perspective and experience new views. Empathy with humans and non-humans evolves in new encounters and relies on resilience. The power of art and poetry sustains this healing process and allows renewal. Including and accepting our imperfections and our vulnerable side and the way we handle these therefore generate a personal growth that grants survival despite traumatic experiences. As the poet remarks, ‘somehow a miracle’ happens in ‘the movement of a river’s/consciousness/ that knows more than you will ever know’. In her poetical and artistic analysis, Sharman becomes part of an environment that is our natural surroundings, giving us peace and sustaining us.

Sing me down from the dark by Alexandra Corrin-Tachibana. £10.99. Salt Publishing. ISBN 9781784632762

East and the West clash and merge in Alexandra Corrin-Tachibana’s debut collection. Japanese and European cultures criss-cross and interweave in family relationships, love, sex and food. Identity is in flux in a reality that is often blurred and uncertain. Rituals rule but are often ambiguous and confusing. The protagonist retraces ten years of her life in Japan, her marriage and the birth of her son. The memories are experienced at the threshold of two languages, moving from English to Japanese with the aid of translations. It is a cultural and physical movement from one place to the other that conveys a sense of displacement. She is a stranger in the Japanese context despite all her efforts to fit in and be accepted. There is a yearning to belong, to find a place that is home, but she is often pushed to the margins, which is a way of taking control from her. Everything and everybody seem to remind her that she is a gaijin, a foreigner, ‘an outsider person’, though she enjoys oily engawa, miso soup and karaoke:

Two obasan stand on the side of the sento trying to break me. Dete kusadai! Dete kusadai! I sit in a steaming pool. I don’t want to leave. ‘I don’t understand.’ I say, in English. I am the only gaijin. The white-uniformed women wait it out until I emerge to grab my modesty towel. I’ve broken bathing rules posted in the changing room lockers, because of the tiny snake tattoo, on my left buttock.

(‘Japanese Bathing Etiquette’)

She will never be considered one of them, not just by friends and acquaintances but also by her husband. She must take with her an alien registration card at all times, which is an ID that may mean she gains the respect and consideration that Japanese people show towards foreigners but it also denotes a procedure that sets up clear borders between the inside and the outside. It is a makeshift acceptance that subtly underlines her state of being an outsider rather indicating that there is harmony in the relationship. Contradictions emerge, revealing misunderstandings and sometimes verbal abuse. The relationship with her husband flourishes at first:

Yoshiteru, your name, like

ashiteru – I love you

you sang it to me at karaoke –

sweet as sukiyaki beef.

You loved my bob,

my boobs, my waist,

my heart-shaped face.

(‘Love-love desu ne!’)

But even during their honeymoon he wishes to go home early as he misses his country. In their relationship, tenderness and estrangement alternate with erotic peaks and moments of loneliness. ‘East is East and West is West’, her father warns her, but the protagonist is enchanted by the Japanese way of travelling through the seasons, the fabulous sushi and the excitement of visiting new places and having challenging experiences such as wakeboarding in the Tenryu River. When she goes back to the UK she misses Japan; she lives in between two cultures and is uncertain about where she belongs. This situation makes her open to new possibilities despite the crisis that is taking place in her marriage. She is a migrant, a condition that defies all certainties and seems to reflect the human condition in a wider perspective. Moving from one place to the other and experimenting with different realities and alien cultures is not only a way to grow but also a search for freedom and a strategy for coming to terms with our temporary state in this world.

The poems often develop in short, fragmented lines, snapshots of the places the protagonist visited, as in the poem ‘10 Years; 10 Places’, which revisits her past memories; she remembers food that symbolically traces the phases of her relationship with her husband too. When it is time for a farewell, ‘doesn’t’ and ‘don’t’ highlight her wish to express herself and her refusal to give in to rituals that she does not agree with or she does not engage with:

She steps out onto our balcony in bare feet

our toddler follows her as she hangs laundry

She does not wear straw slippers

she does not rinse sticky rice before cooking

(‘My Darling is a Foreigner’)

I don’t eat giant Miho strawberries,

of Fuji apples dressed

in polystyrene doilies, like tutus.

(‘Farewell to Karaoke’)

The form adopted by Corrin-Tachibana therefore reflects her ideas in the skilful use of English and Japanese that weave the complex thoughts about loss and gains that are implied in her search for a home in a reality where everything is provisional. Words come to her rescue in poetical forms when her marriage collapses and she embarks on a new relationship that gives her joy and renews her hopes. It is a poetical and passionate liaison in which shared interests and desires envisage a future together:

we laugh, and I want more of this.

I want more of kicking up

my peep-toe heels, holding hand

in fields, as elderly scouts

(‘The day I tell you I had no knickers on when the Sainsbury’s man called’)

They grow ‘into each other’, gathering ‘mutual points of reference’. The nightingale once caged can now ‘fulfil their migratory urge’ and fly free in the open sky. The collection delineates the poet’s ten-year life in Japan and reveals a deep emotional involvement with its culture and people. The personal experience is revisited in poetry in which the two languages alternate and merge, with never-ending and surprising implications.

Carla Scarano D’Antonio lives in Surrey with her family. She obtained her Master of Arts in Creative Writing at Lancaster University and has published her creative work in various magazines and reviews. Her first short collection, Negotiating Caponata, was published in July 2020 by Dempsey & Windle. She completed her PhD degree on Margaret Atwood’s work at the University of Reading and graduated in April 2021. Her second collection, Workwear (November 2022), is published by The High Window. http://carlascarano.blogspot.com/

http://www.carlascaranod.co.uk/

*****

Robin Thomas’s The Weather on the Moon reviewed by Janice Dempsey

The Weather on the Moon by Robin Thomas. £9.99. Two Rivers Press. ISBN 978-1-909747-97-5

This is the third opportunity I’ve taken to access Robin Thomas’ universe through his books. It’s a fragile world, whose unexpected strengths derive from his elastic, unsentimental grasp of reality. Thomas grapples with existential issues in a variety of ways: through poems about paintings and music; by animating and interrogating inanimate or non-human things in his environment (‘He talks to the house that once he lived in’); and by looking directly at tropes and expectations to re-evaluate their meaning. It’s not surprising that I find myself smiling with recognition as I read Robin Thomas’ view of the universe in its enormity and its dispassionate enforcement of the ‘laws of nature.’ After all, ambiguity and contradiction are embedded in comedy of the most serious kind.

Thomas approaches ekphrastic poetry by launching from each painting’s imagery a personal thesis. At home with the surrealists’ argument that art and reality must be seen as separate, in ‘The Treachery of Images’, he turns Magritte’s joke on its head: This is indeed a pipe, but a pipe in the wrong place, on the wrong scale — and the final joke is that Thomas says he has painted a corrected version of ‘Ce n’est pas une Pipe’ — ‘Que n’existe pas, for obvious reasons.’ Later, in ‘Bambino Vispo’, after a rapturous description of the Madonna and her pose as ‘an amaranthine reverence before the son of man,’ he quotes ‘the infant — naked, pink, all wriggling arms and legs — the Type of itself’:

Less

of the adoration please.

For heaven’s sake just pick me up,

I’m hungry

The title of the collection is taken from ‘Danger Zone’ which I feel epitomises some of Robin Thomas’ themes and his approach to poetry. This five-part sequence comprises two prose poems and three lineated poems. First, a meditation in a dark wood (the italicised afterword tells us ‘This is a place where nature is here with me, not there with me in it.’). It’s followed by ‘Fire Flight’ which describes butterflies in the wood, and refers to the premise that a butterfly wing’s movement will affect the weather on the other side of the world: ‘These, beautiful as they were, had no more than a week to affect the weather in New South Wales, to help or hinder the fire fighters.’ And in a surreally logical extension of the premise, foxes playing in his garden may be influencing the weather on the moon. Here the afterword is: ‘I have boxes of time, stacked at one side of my study, taking up much needed space. One day, when they are all empty, I will throw them all out. Oh, what will I do with the extra space?’

I loved the third poem in this sequence, in which a dialogue that takes place between the narrator and a house where he grew up reveals the kindness and protectiveness of houses. In the fourth, ‘When I think about sanctuary’ the narrator considers the value of safe places, and in the body of the poem concludes that the poet’s writing space is the most effective sanctuary available, but that ‘It’s amongst the nuisance, noise, danger and delight of the world that you need to be.’ But the afterword then admits: ‘Sometimes I look up from my writing and hit a surge of sadness’. The fifth poem in the sequence is about loosening, relaxing, represented by the image of a rush-hour railway platform slowing to a standstill as ‘The shadows, which have been lengthening all afternoon, merge slowly into the stillness, when the mad growth all round freezes and sleeps, like the graves it is its business to reclaim.’

This is a book that I’ll keep at the front of my bookself, to be reread and dipped into often. In almost all the poems, death runs in an undercurrent that is as inevitable as life, an undercurrent that we try to avoid dwelling upon — in ‘There are games of competitive quoits’, distractions are offered, as though we’re on the Titanic’s final voyage. and in ‘Answers’ an oracle (or perhaps a priest?) answers pedantic questions with pedantic answers, but balks at a serious and unenunciated question, to which there is no admissable answer. But it’s doom with a light touch, written by a poet who has accepted ‘A Species of Disappointment’ as the human condition, who loves music and art, and who observes:

No point in being kind,

but you might as well be.

(‘Unmendable’)

Janice Dempsey publishes poetry at dempseyandwindle.com, where Cafferty’s Truck by Robin Thomas was published in 2021

Reblogged this on The Wombwell Rainbow.

LikeLike