*****

POETRY

Iain Crichton Smith: Deer on the High Hills: Selected Poems, edited by John Greening • Edna St Vincent Millay: Poems and Satires • Louise Glück: Winter Recipes from the Collective • Sheri Benning: Field Requiem • Hannah Lowe: The The Kids • Annemarie Austin: Shall We Go? • Tishani Doshi: A God at the Door • Myra Schneider: Siege and Symphony • Anne Ryland: Unruled Journal • Frank Dullaghan: In the Coming of Winter • Omar Sabbagh: Morning Lit: Portals after Alia • Michael Crowley :The Battle of Heptonstall • Robin Thomas: Hum • Barry Smith: Performance Rites • Sarah Watkinson: Photovoltaic • Hubert Moore: Owl Songs • Carole Coates: When The Swimming Pool Fell Into The Sea • Candy Neubert: privacy • Greg Freeman: Marples Must Go! • John Looker: Shimmering Horizons

ANTHOLOGIES

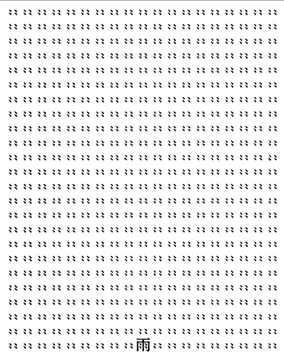

Concrete Poetry, A 21st Century Anthology edited by Nancy Perloff

PAMPHLETS

Rosie Jackson: Light Makes It Easy • Kathleen Bainbridge: Inscape • Alison Binney: Other Women’s Kitchens •

TRANSLATIONS

Salvatore Quasimodo: Complete Poems, translated by Jack Bevan • After Dante: Poets in Purgatory • Louis de Paor: Crooked Love/Grá fiar • Muhyiddin Ibn ‘Arabi: The Translator of Desires

REVIEWERS

David Hackbridge Johnson • Sibyl Ruth • Kathleen Bell • Ken Evans • Patrick Roberts • Rona Fitzgerald • Alan Price • Ruth Sharman •Pippa Little •Janice Dempsey • Alex Josephy • Carla Scarano • Neil Fulwood • Lorri Pimlott • Kathleen McPhilemy • Stephen Claughton • Stephen Payne • Roger Elkin • D A Prince • Caroline Heaton • Ellen Phethean • Sam Milne • David Cooke • Colin Pink

Iain Crichton Smith’s Deer on the High Hills: Selected Poems reviewed by David Hackbridge Johnson

Iain Crichton Smith: Deer on the High Hills: Selected Poems, edited by John Greening, Carcanet, Manchester, 2021. £14.99. ISBN: 978-1800170940

From the gentle undulations of the Ochil Hills to the higher peaks of the Crainlarich Hills – those sharp backbones of Ben More and Stob Binnein – there lies a geography that seems to cry out for poetry. The flanks of the mountains bear myriad colours that change with the weather. Exposed rocks sing with minerals and the heather paints purple in shadows. ‘Look there are the deer’ – this from my good friend Iain Colquhoun, a former estate manager in this part of Scotland. I can’t see anything and need binoculars to spot the beasts – something Iain does with the naked eye. In truth I only see the suddenly magnificent and unmistakable stag when it moves. Did it lift its nose to the wind haughtily as if sensing the focusing lenses?

There is poetry for these hills and for the deer that patrol them – a wonderful example is found in the recent selection from the poetry of Iain Crichton Smith published by Carcanet – it is the poem that gives the volume its title: ‘Deer on the High Hills’. Whereas a tourist like myself, albeit a ‘Caledonophile’, might pen a few heady hymns to nature by way of contrast to the diesel soot of Tooting, Crichton Smith’s purpose is to view the deer from multiple perspectives – their survival ‘balanced on delicate logic’ , the sense of mystery we like to burden them with, their regal bearing – ‘like fallen nobles’ , and a beauty that can turn savage – ‘He might suddenly open your belly / with his bitter antlers to the barren sky.’ The deer is both real and emblematic in a poem that argues between the two – are the roaring deer by ‘the appalled peaks’ creatures for mythical loading, or is it ‘Simply a matter of rutting’? Despite this physical reality the poet can’t help investing the land with elegiac strains – ‘an empty country // deranged, deranged’ – but any hope of renewal through bardic nostalgia is ruined ‘by barbarous bones, / plucked like a loutish harp’.

The editor of the volume, John Greening, serves a generous helping of Crichton Smith, a poet he feels is lacking the status afforded to other Scottish poets of his time: Sorley MacLean, Norman MacCaig and the Orcadian George Mackay Brown. Although ‘Deer in the High Hills’ remains perhaps Crichton Smith’s finest achievement, there are many other magnificent poems and many are found here. Greening has attempted to cover not only work in English but also Crichton Smith’s translations of his own work in Gaelic – so we get lines such as these from the prose poem ‘Eight Songs for a New Ceilidh’: ‘But as for me I grew up in bare Lewis without tree or branch and for that reason my mind is harder than the foolish babble of the heavens’. The poet immediately shifts from the Isle of Lewis to Hiroshima and then to Belsen, dramatic and alarming swerves that posit Crichton Smith as no mere regionalist but as Greening is keen to emphasise in his ‘Foreword’, a poet of Europe. Like Sorley MacLean and like Hugh MacDiarmid, Crichton Smith can vault mountains and jolt perspectives.

However, Crichton Smith does return to Lewis frequently, if only to make stark contrasts by means of generous humour. No ‘revered Vermeer’ resides on the island but you will find ‘the constancy / of ruined walls and nettles’. And a fierce Calvinism is abroad: ‘I hear / a sermon tolling, for your theatre is / the fire of grace, / hypothesis of hell, a judging face’. These pithy recognitions of the harshness of upbringing are taken from Crichton Smith’s 1986 book, A Life – a work that is more an autobiography of observations that of personal confession. And how acutely the poet observes! Descriptive writing vies with flashes of speech – the corporal, ‘moustached, Hitlerian, ‘You play fair with me / and I’ll play fair with you. Otherwise….’. We get such rich juxtapositions as, ‘Pale girls at evening on neon roads – / the marble halls of Rome.’ Greening’s inclusion of these selections from A Life makes one immediately want seek out the entire volume; surely a credit to Carcanet’s enterprise in bringing these poems out once more.

In all these poems Crichton Smith evinces a refusal to paint easy landscapes of either earth or mind; if he feels the pull of islands despite a volatile muse activated by events from all over the world, it is not in the way of a quiet homecoming to Lewis, but to taste the reality of land surrounded by water: ‘There is no island / The sea unites us. / The salt is in our mouth.’ Within this unity of water Crichton Smith’s work abounds in variety. This selection of poems, together with Greening’s very useful and perceptive ‘Foreword’ and ‘Afterword’ should find readers for whom Crichton Smith is a new name and will reacquaint those for whom he is already a classic.

David Hackbridge Johnson began composing at the age of 11 and has written works in all genres. His works have been widely performed. and include 15 symphonies, 4 of which have been recorded on Toccata Classics. He is also a poet.nson

*****

8

Edna St Vincent Millay’s Poems and Satires by Edna St Vincent Millay reviewed by Sibyl Ruth

Poems and Satires by Edna St Vincent Millay, £14.99 Carcanet. ISBN 978 1 80017 167 1

This selection of poems was unsettling in the best possible way. Too often I convince myself that I’m familiar with poet’s work – aware of their distinctive qualities – only to find out I’m wrong. Before reading Poems and Satires I’d thought of Edna St Vincent Millay as a rather outdated sentimental writer. This belief was based on few heavily anthologised pieces, for example the sonnet which begins:

What lips my lips have kissed, and where and why.

I have forgotten.

The piece goes on to describe how:

…….in my heart there stirs a quiet pain

For unremembered lads that not again

Will turn to me at midnight with a cry.

Lost love is what we expect women to write about, even though it’s not exclusively a topic for girls. ‘What lips my lips have kissed’ is a Petrarchan sonnet. Petrarch himself produced over 300 sonnets about his unrequited love for Laura.

Another error was to assume that the surface accessibility of Millay’s work meant it must, in some way, be confessional. (This isn’t to minimise the power of confessional poetry. Even a century later, isn’t there a frisson when a woman says she’s lost count of her lovers?)

Poems and Satires helpfully give the dates when each poem appeared in book form: ‘What lips’ belongs to a 1923 collection. This reminds us that even though Millay’s sonnets are worlds away from the innovative poetics of Eliot and Pound, her voice is a contemporary one. She might be seen as poetry’s equivalent of a Gatsby Girl, one of Evelyn Waugh’s Bright Young Things. This impression may be reinforced by the book’s (rather gorgeous) cover which features a plate by George Barbier, the pre-eminent fashion illustrator of this era.

But the poem first appeared in a 1920 issue of Vanity Fair. Given that other work from this period – for example Millay’s Modernist play ‘Aria di Capo’ – reveals an anti-war stance, it seems possible that those ‘unremembered lads’ might be an allusion to the thousands of US servicemen who were killed and injured in World War I.

Tristan Fane Saunders’ introduction describes Edna St Vincent Millay’s rise to fame. The story is oddly reminiscent of today’s literary culture with its fevered disputes and discoveries of ‘hot’ new talent. In 1912 Millay, then aged twenty, entered her poem ‘Renascence’ into a competition. At the time she had a Cinderella-like existence-looking after young siblings in a poor part of town. Millay’s entry was longlisted and, after inclusion in an anthology called The Lyric Year, controversy over whether it should have won brought her to public attention. Barely a decade later, was Millay a celebrity – and a winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry.

The first section of Poems and Satires is made up of Millay’s sonnets. Reading them is a reminder that, no matter what shifts in taste occur, the sonnet remains the ideal form for the poet who wants to pack lashings of virtuoso technique into a small space, But to pull off a sonnet sequence – where each poem forms part of a narrative – shows an even higher level of accomplishment. Millay’s ‘Sonnets from an Ungrafted Tree’, which deals with a woman’s return to look after her terminally ill husband, is extraordinary.

And sonnets are versatile; they do not have to be sparkling or flashy. The sequence shows a kind of concealed skilfulness, a depth of insight. It nticipates those poems in which UA Fanthorpe showcases the voices of marginalised people. Here Millay considers how her protagonist came to marry:

Not over-kind, nor over-quick in study

Nor skilled in sports nor beautiful was he,

Who had come into her life when anybody

Would have been welcome, so in need was she.

In a subsequent sonnet:

The doctor asked her what she wanted done

With him that could not lie there many days

And she was shocked to see how life goes on

Even after death, in irritating ways.

In passages like these Millay explores love and death in words that are bracingly matter-of-fact – ditching the conventions of celebration and elegy. Few other poets of that time were so clear about the limited options offered to women, and it’s noteworthy that Millay herself sought to evade these limitations.

Tristan Fane Saunders mentions that Millay was called ‘Vincent’ by friends and family. He also alludes disapprovingly to a 2018 Guardian review which characterised her as ‘a sexually adventurous bisexual’.Yet in his otherwise admirable essay, it’s Millay’s male lovers who bag all attention. Readers who would like to know about her relationships with women may wish to consult http://lgbthistoryproject.blogspot.com/2012/02/edna-st-vincent-millay-1892-1950.html

The book’s second and third parts are devoted, respectively, to Millay’s lyric poetry and her satires. There is a generous selection of poems from the 1930s, a decade in which her status had (unjustly) declined. Overall this lets us see just how many personas Millay deployed. Her work is complex, multiple, diverse.

Having worked through Poems and Satires in December, it’s unsurprising that I lingered over ‘The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver’ whose climactic scenes take place at Christmas. Here Millay draws on traditional English forms and folklore

Men say the winter

xxWas bad that year;

Fuel was scarce,

xxAnd food was dear.

A wind with a wolf’s head

xxHowled about our door,

And we burned up the chairs

xxAnd sat on the floor.

Millay’s pen gives these traditions a distinctive American twist, perhaps informed by her own early experiences of hardship, and the Depression of 1920-21. The poem later reached a new audience, thanks to the singer (and balladeer) Johnny Cash. In 1959 he sought permission from Millay’s estate to write a musical backing for ‘Harp-Weaver’. This was granted and three different live versions are available on YouTube, as well as a recording on Cash’s 1963 album The Christmas Spirit

While this ballad – a narrative of magic, maternal love and sacrifice – shows Millay’s ability to work within poetic convention, the prose Satires emphasise her subversive side. There are a good few extracts from her 1924 collection Distressing Dialogues, short pieces written for Vanity Fair under the pseudonym Nancy Boyd. (I felt some distress of my own on learning this book is now out print.) An especial favourite was the spoof agony column entitled ‘Art and How to Fake It: Advice to the Love-Lorn.’ This is the opening of a letter from someone who signs herself LANDLADY:

Miss N Boyd,

Dear Madam:

I am a plain, honest woman, with a house in Waverly Place where I let Furnished Rooms to Artists. I have a lot of trouble with them. In the first place they are awfully careless about their Rooms, they never hang-up anything, there always dirty shirts on the floor, to say nothing of bread-crusts and rinds of ham bologna. I have an awful time with them

But the landlady’s chief gripe is the artists’ failure to pay rent. ‘Miss Boyd’ (Millay is neither plain nor honest) replies:-

There’s only one thing to do… Buy a tin bank and place it on the table in the hall. Above it tack the following placard:

FREE THINKERS! FREE LOVERS AND FREE BOOTERS!

If you have any Heathen Pity in your Heard Drop a Nickel in the Stot for the Starving Baby-Anarchists of Russia

WHO DOES NOT CONTRIBUTE TO THE CAUSE OF ANARCHY IS MID-VICTORIAN

I think you will have no further trouble.

It is understandable that this kind of youthful esprit came to overshadow some of her subsequent work. Even so I think it’s is a late sonnet ‘I will put Chaos into fourteen lines’ that will live on my mind. Here Chaos is seen as masculine; it the female hero’s mission to subdue him in an act of ‘pious rape’. The concluding lines may serve as a metaphor for Millay’s unique artistry:

He is nothing more nor less

Than something simple not yet understood;

I shall not even force him to confess;

Or answer. I will only make him good.

Sibyl Ruth is a poet who also writes fiction and sometimes translates poetry. She’s a former winner of the Mslexia Poetry Competition. Her English versions of eight pieces from Heine’s ‘Buch der Lieder’ appeared on The High Window website in October 2021

*****

Paul Dehn’s At the Dark Hour: Collected Poems 1935-1965 reviewed by Alan Price

Paul Dehn: At the Dark Hour: Collected Poems 1935-1965. Edited by John Howlett. £15. Waterloo Press. ISBN: 978-1-906742-99-7

Paul Dehn lived from 1912 -1976 and had three work identities. He was a poet, scriptwriter and spy, and hiding lightly behind those distinctive roles was Paul the gregarious Jewish gay man.

In the 1940’s Dehn wrote a spy training manual that’s still revered by the security services but espionage never became the subject of his poetry. Yet WW2, the cold war, and its apocalyptic consequences, the atomic bomb, did haunt his writing directly and covertly as an ominous reminder of the worst to come with Dehn expressing feelings of anger, unease and anxiety over the nuclear age.

You’ve only to read the first poem “An Explanation.” from his collection called The Days Alarm (1949) to perceive how mankind’s ability to destroy, many times over, the beauty of the natural world is poignantly apparent:

Then, if the desperate song we sang like storm-cocks

At the first flash, survives the ultimate thunder

To be dreamily misunderstood by the children of quieter men

Remember that we who lived in the creeping shadow

(Dark over woodland, cloud and water)

Looked upon Beauty always as though for the last time

And loved all things the more, that might never be seen again;

Dehn has been wrongly described by some critics as an apocalyptic poet (mainly because of a 1961 collection of clever and ruthless rhymes called Quake, Quake, Quake) which is an anti-nuclear blast. But we can drop apocalyptic for the word elegiac. Dehn’s poetry isn’t simply suffused with images of destruction but accompanied by a deep sadness and tentative hope for renewal. Even in the amazing poem The Sunken Cathedral (after Debussy’s piano piece) there’s a bleak form of resurrection as the cathedral’s bell, though it disturbs the very alien birds, and all is gone, refuses to be silent:

The rest you have heard: how, in the bronze light

Of certain winter dawns too cold for wind,

It surfaces

With a sound like thunder and the water streaming

From windows open to the terrible sky.

Then, among iceberg-tall

Towers, chiming,

The cracked bells cry havoc and a white

Choir of gulls, not known on land,

Goes wailing among the aisles.

Poems such as The Sweet War Man is dead and Armistice are very much 40’s war poems. Yet their power to disturb and move hasn’t dated them. After urgent imagery about the renewal of life, and the land, Dehn fiercely pulls you up sharp, at the end of Armistice, to remember the dead of the war as now being ‘bread in the bodies of the young’ and that bread died screaming ‘Gangrene was corn, and monuments went mad.’ Armistice is an uncomfortable poem for a Remembrance Day service as its universal concern is for how we can so easily forget or mis-remember the casualties of history whilst tributes glibly and blindly mask the losses that occurred.

As well as a war-consciousness, that unlike some other 40’s poets, was never limited or held back by WW2, Dehn achieved a lyrical tone of voice most apparent in poems like Mourne Mountains, Fern House Kew, In the Spring and in the especially captivating At the Buca de Bacco:

Over and over, to-night

The pianist plays by the reef

In the sea-green light

Of lamp under leaf.

His fingers are fish,

Leaping

The surf of a glimmering keyboard;

And over and over the drummer is keeping

Time, with the swing and the swish

Of waves on the seaboard.

But not all of his poems completely work. The flawed ones are those when the lyricism appears to come too effortlessly. Dehn never wrote a poem that wasn’t beautifully crafted yet sometimes he’s a little old fashioned, writing verses that sound a bit art-full, like he’s revisiting

Edmund Spenser.

Only a handful of Dehn’s poems can be called great. Armistice, The Sweet War Man, Sunken Cathedral and Romantic Landscape justify that claim. The book has been edited by John Howlett who finds the poem Romantic Landscape to be ‘a tour de force which deserves to stand as amongst the finest lyrics of the century and acts as an apt summation of many of the main themes found within this smallish body of work.’ I agree with Howlett and found ‘Romantic Landscape’ to be a small masterpiece.

At the beginning of the poem it appears to be ekphrastic. Yet the title of the painting or artist isn’t supplied (Hewlett thinks it’s Claude). It’s an Arcadian scene of a boy watching cattle near empty groves and an abandoned temple: all ‘doubly dead’ because the scene only exists in the artist’s imagination. It’s been seven years since the war and Dehn sees the painting as resembling the deadness of a bombsite outside of his window. A wonderful intersection of time, memory, cultures past, present and future decline is realised when the city (London) is in the future made rubble:

And a wingless Eros halts the silently darting

Traffic of lizards in a green Circus,

(For me that stunning image appears more applicable to climate change than nuclear Armageddon).

When the poet turns from his reflections to face the canvass the sun is setting not just on the day but seemingly on the cultural achievements and progress, of his own time, where Elysian dreams now appear incompatible with, what is for Dehn, ‘our present hell’:

And I turn my face to the wall where, bright on the canvas,

The last light of England moves over Arcady

Two thousand years ago.

Dehn’s poetry was regularly anthologised (Poets of the Forties edited by Robin Skelton), Philip Larkin’s The Oxford Book of Twentieth Century Verse, collections were published in the fifties and sixties and Dehn was highly praised by The Times in 1952 for his lyric power. However in the last 30 years his name vanished from the poetry scene. Dehn fell out of fashion or didn’t fit the agendas of anthologists. At the Dark Hour is a remarkable collection that I keep on returning too. Paul Dehn needs to be re-appraised, beginning now.

Alan Price is a poet, short story writer and critic. His film and book reviews regularly appear on the websites Magonia and London Grip. He has published fiction, poetry chapbooks and three full collections among which are two published by The High Window Press: Wardrobe Blues for a Japanese Lady and The Trio Confessions.

*****

Louise Glück’s Winter Recipes from the Collective reviewed by Kathleen Bell

Winter Recipes from the Collective by Louise Glück, Carcanet, £12.99, ISBN: 9781800171800

In her latest collection Louise Glück’s explores a liminal space that is at once strange and familiar. Ageing, bereavement and death are common experiences, in life as well as in art, yet however much we prepare ourselves, they are liable to arrive as a surprise which time or our own efforts may soften into the realm of the known. Glück’s poems, with their wondering, questioning approach, intensify the surprise by taking the reader into a place of estrangement so acute that some of the characters within them seem partly absent from their own lives, even as the poems themselves remain anchored in known and in recognizable worlds. For example the sequence ‘Autumn,’ about old age, takes place in what may be an old people’s home with benches set outside and a conversation takes place. Some of the conversation is practical, if sweeping: ‘Old people and fire, she said. / Not a good thing. They burn their houses down.’ Like many of Glück’s lines, the apparently direct language works on more than one level, suggesting without forcing a metaphorical meaning.

From another poet such familiar images as ‘The smell of burning leaves’ or ‘Stars gleaming over the water’ might seem banal and close to cliché. But in the strange surroundings and intercut with a conversation that can also address the nature of life, they have the potency of a sharp reality invading the slipperiness of a dream world. The images don’t stand alone but are part of an ungraspable world which forces reflection and questioning:

How heavy my mind is,

filled with the past.

Is there enough room

for the world to penetrate?

It must go elsewhere,

it cannot simply sit on the surface –

This may be about the sister’s mind, the poet’s, or, by extension, the mind of any reader.

As the poems in this collection deal with ageing, they often feel the weight of a past that must be revisited. Thus in ‘A Children’s Story’ the parents, who begin the poem as king and queen with a carload of princesses, make a return journey from countryside to city, understanding that:

Despair is the truth. This is what

mother and father know. All hope is lost.

We must return to where it was lost

if we want to find it again.

Those big abstractions – despair, truth and hope – work only because they emerge from the half-familiarity of children chanting in the back of a car and the vision of rural life lost (‘cars and pastures are drifting away’).

This use of the known and familiar is perhaps at its strongest when addressing – or skirting round – the theme of death. In ‘The Denial of Death,’ which takes its title from Ernest Becker’s book without addressing its political implications, there are recognizable elements: hotel, concierge, passport, postcards and so on. Yet the semi-abandonment of the narrator, the journeys taken and not taken, the brief messages and encounters blur the identifiably real with other events for which they might stand. The poem itself is so conscious of the potentially reductive nature of metaphors and artifice that it can allude directly to conventional literary devices only to question and undermine them:

I could hear the clock ticking

presumably alluding to the passage of time

while in fact annulling it.

and:

Concierge, I said. Concierge is what I called you.

And before that, you, which is, I believe,

a convention in fiction.

Yet the strongest element in this poem is its sense of abandonment and personal loss. When a passport is lost and the speaker denied entry to a hotel – ‘a beautiful hotel, in an orange grove, with a view of the sea’ – they are left outside, on a blanket, sometimes fed or pelted with chocolates or in receipt of post. When the lost passport arrives its photo shows only a former self. And in the period of waiting time itself has ceased to move in a straight line but becomes ‘a circle which aspires to / that stillness at the heart of things.’

Two repeating themes in Winter Recipes from the Collective are children (present, absent or remembered) and the narrowing of life in age to something close to its necessities. The children in the first poem begin as simile:

Day and night come

hand in hand like a boy and girl

pausing only to eat wild berries out of a dish

painted with pictures of birds.

But as soon as they pause and eat from a very specific dish the comparison with day and night diminishes and they become plausible children, if not in the real world or memory at least in the world of the imagination. Like figures on a willow-pattern plate, the boy and girl recur, flying away then standing ‘on a wooden bridge’ and calling ‘How fast you go’ as the speaker falls through a multitude of worlds. This would be bleak if not for the tenderness of the speaker who at one point sings ‘as mother sang to me’ and concludes the poem with the stand-alone line ‘I touch your cheek to protect you –’

The four-part poem which gives its title to the collection offers a wintry life of hardship in which old men, with difficulty, enter a wood to collect moss which is treated by their wives so that it can be used in sandwiches when no other food is available. There is no delight in this moss; ‘it was what you ate / when there was nothing else, like matzoh in the desert, which / our parents called the bread of affliction’. There is courage in this diminished life, which may be a small sign of hope, but there is little comfort.

The cover of Winter Recipes from the Collective offers the reminder, in red print, that Louise Glück was recently a ‘Winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature.’ Such prizes often go to writers who are overtly concerned with the political issues of the day. Glück’s poems in this collection are, by contrast, quietly compelling as they suggest stories of sorrow and loss which are fundamental to our shared human existence.

Kathleen Bell’s first full poetry collection, Disappearances (Shoestring, 2021) is now available. She is also the author of two chapbooks: the lockdown sequence Do You Know How Kind I Am (Leafe Press, 2021) and at the memory exchange (Oystercatcher, 2014). Originally a Londoner, Kathleen is now an East Midlander by adoption. Since her happy escape from academia she now has much more time for reading, writing and reviewing poetry.

*****

Sheri Benning’s Field Requiem reviewed by Ken Evans

Field Requiem by Sheri Benning. £11.99. Carcanet. ISBN: 9781800171510

‘Only dispossessed people know their lands in the dark’, wrote Anglo-Irish writer Elizabeth Bowen, and on a reading of Sheri Benning’s fourth poetry collection, one is reminded of ‘place’ as personal mythology in a poet’s work. Or rather than ‘place,’ perhaps a more accurate word for Benning’s sense of location would be ‘settlement’. ‘Settlement’ as in where an individual settles to live, but also referencing the collective, of group habitation; and as a pact between those who settle there and Nature; and specifically, between human activity and Nature as in climate and the current crisis.

In Field Requiem, Benning explores the lost world of those who farm on the land and live with the vicissitudes of its’ climate, its’ increasingly corporate industry of production, and throughout the collection, the pact between farmer and Nature is freighted with spiritual overtones. The poems titles, as well as many epigraphs, allude to Biblical parable and religious liturgy, such as ‘Viaticum’, ‘Vespers’ or ‘Extreme Unction.’ Farming is seen as vocation, as in ‘taking the cloth.’

‘Settlement’ here also refers to colonisation, for just as the multi-national corporates have forced out the small farmer in favour of large-scale, intensive farming, (50,000 small farmers have left the land in recent decades), so the first white settlers displaced the aboriginal land-dwellers, on ‘the cracked-open casket of the nation’s turn of the century bullshit-/promises…’

The small farmer, just as the original land-dwellers, have become deracinated. Benning writes movingly in ‘Great Plains Auctions’ of how farmers (like her own father) would bid extra at auctions to allow a fellow farmer to make their getaway from the land: ‘Sure, we were sad to see our neighbours go, / bid extra on their socket sets, air compressors / leftover five-gallon pails of hydraulic oil. / Sold! The auctioneer’s speakers / rattled in his truckbed… We told ourselves, if they could, they’d do the same.’

But ‘our place’ calls to us, in a sense we never leave it, and is a storehouse for our memories, and as in ‘Minor Doxology’ –

‘…because place calls to place /inside us, he is seventy in the kitchen, / even as he is twelve in the farmyard.’

Benning evokes this sense of place through an incantatory, accumulative use of detail that by naming, seems to sanctify the place, and make it ‘holy.’ To ‘speak the image’ not only draws us in as reader through the specifics of ‘naming’, but it also honours and memorialises the ‘thing’ spoken of. At times this has almost have the simplicity of a workshopped ‘list poem,’ but at its best it builds a picture by turns elegiac and angry, as Benning gains energy from her own ‘poetry of witness and warning’ (and ‘mourning’).

This method is established from the very first line of the opening stanza of the poem that introduces the collection, ‘Winter Sleep’, as ‘casks of cherries, plums, / boiled melon, beef tallow, pig bladders blown / and tossed by children / mothers stirring stock, / kidneys, hearts pressed with aspic,….casings scraped and stuffed, allspice, cloves,’ create a picture of busy-ness and abundance, of toil and produce, making and loss.

The repetitions are precise, the observation of the natural world acute, which means the litany of description never becomes bucolic, idealised. As a farmer’s daughter, albeit one forced from the land, Benning is unsentimental about how hard farming might be. In ‘Harvest’, there’s ‘thin smoke in the middle distance, / as though harvest was a war.’ And snow becomes a ‘cool chrism /on last season’s wounds.’ (My italics.) In ‘Vespers’, a January prairie is ‘a knife held to the throat.’ ‘Vespers’ has the hypnotic rhythm of a sung psalm, as ‘Infant skulls, allium bulbs, / pulp rich and sweet with utero-dreams / of silver light in birch leaves, / of grasses low suss.’

Benning has made a record and borne witness to a disappearing lifestyle, that is also her own personal culture of childhood – sweet, nostalgic, occasionally macabre.

There is an understandable tendency, given her history, to side with and celebrate the small, diversified farms and their farmers, while lambasting the multinationals as ‘land criminals’. I believe she draws inspiration from Wendell Berry, the US farmer-poet and the ideas of an ideal ratio of ‘Eyes to Acres’ (too many acres that you cannot see and feel – you do not ‘know’ in all its vagaries, moods and weathers – leads to bad, exploitative land practises and management.) The drive for food surpluses today, leads to a poisoned, reduced land in the future. In ‘Winter Sleep’, ‘I wake to 6000 acres, high clearance sprayers / with 140-foot booms. Sulfur, phosphorus, nitrogen, / potash. Harvest done by drone. Yields downloaded / into $750,000 air seeders.’ The accumulation of numbers gives a sense of the industrial mechanisation, just as the list of herbs and flowers and crops in other poems give a feel of natural abundance and variegation. Whilst this may be hard to disagree with, mechanisation often leads to cheaper food for the less well-off who struggle currently, for one example, to find the money for say, organic vegetables and meat, and not all small-scale farmers are productive, or always demonstrate good husbandry of the soil. And the toughest burdens of smaller-scale farming – what is hard relentless work, let’s face it – often fall on minorities, the women partners and wives of male farmers, and a cadre of the ’precariat’ – low-paid, seasonal, zer-hours contract workers.

However urgent the political debate underlying these poems of grief and rage, loss and lyric yearning, Benning’s skill is to elaborate these in most cases without overwhelming the poetry to didactic purpose, yet clearly delineating the sense of grief and outrage on behalf of the land and the people, the livestock and crops, and delineate what Benning sees as a more harmonious way of working with the land and Nature. A memoriam and augury for these troubled lands and sorrow for a way of life disappearing under increasing coercion from global forces – both natural and man-made – whose interconnectivities we are all having to begin to know and try and understand.

Ken Evans won the Kent & Sussex poetry competition In 2018 and Battered moons in 2016. Individual poems have featured in Poetry Scotland, Magma, Under the Radar, Envoi, The Frogmore Papers, Lighthouse Literary Journal, The High Window, Obsessed with Pipework, The Interpreter’s House, The Glasgow Review of Books, and The Morning Star, as well as online.

*****

Hannah Lowe’s The Kids reviewed by Patrick Davidson Roberts

The Kids by Hannah Lowe. £10.99. Bloodaxe. ISBN: 9781780375793

Ian Brown, late of the Stone Roses, once responded to the generic ‘What do you think people will think of your music’ question with the undeniably winning phrase ‘Trust the kids – I went to school with some of them’. While the pandemic and his swerve into anti-vaccine idiocy have sadly robbed us of trust in Brown, Hannah Lowe’s brilliant, strident new collection, The Kids (Bloodaxe), reaffirms and furthers our trust in a poet here proving herself as one of our best.

Lowe’s first two collections (Chick in 2013 and Chan in 2016) both enacted a wary eye to definition. This is not to say that they lacked, either in form or in achievement – both of them are remarkable books – but for this reader there was always the sense of something just out-of-sight that was being kept in reserve. Whether it was subject or form was unclear, and that was part of its beguilement, its mystery. In those books there was often the sense of Lowe sizing-up the arena or battleground, before bringing out the heavy guns of a formidable talent. The Kids is that reveal, that application.

The Kids is a book of sonnets, though Lowe’s engagement with and reinvention of that form seems limited when cast simply as that; this isn’t an exercise in formal dues-paying or of gilding the subjects frequently thought of as ‘beneath’ the sonnet or sestina. Where entire books of sonnets by poets achieve is where the poet has identified the form as specifically necessary for the book and subject in question (it’s the difference between wearing a parka because it’s a cold day, as opposed to a fashion statement). The subject here starts as the decade Lowe spent as a teacher in a London comprehensive, before widening to engage with her own younger self, the kid side to being a mother, and also the lost (kids and otherwise).

In fact, the lost give this book both a disquieting and richly infusing quality. Right from the start, the absences are as much a depiction of their importance as they are the missing parts:

My father was dead. I rode to work each morning

through Farringdon, down Charterhouse Street

and saw the same white dog – a terrier – licking

a puddle of blood, leaked by the morning meat

the butchers hauled across their backs to Smithfields.

[…]

He was dead, he was dead. Now what should I do?

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx‘PROLOGUE The White Dog’

The gory aspect of the blood does not rob the contrast of white and red of its brightness, a contrast fueled by the vanished, fresh meat bleeding, and that sense of the moving world and time – from the father’s death to the bike to the butchers – instills that final line with an urgency near-energetic: ‘Now what should I do?’ Others (the poet, even) might read that last line as despairing, but for this reader it rings of impulse and urging, a sense of awakening.

The first section of the book stays in the classroom and among the kids being taught and avoiding being taught. Three poems on ‘The Art of Teaching’ wryly acknowledge the near impossibility of fulfilling that title, but offer jewels nonetheless:

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxIf gloom

has a sound, it’s the voice of Leroy reading

Frankenstein aloud. And if we break

to talk, I know my questions are feeble sparks

that won’t ignite my students’ barely beating

hearts. There is no volta here, no turn,

just more of the same:

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx‘The Art of Teaching II’

The nudging anxiety that flows through a lot of the teaching poems is evident here; Lowe is repeatedly struck by the role that she is playing in the moods and behaviours of the kids in the class (he wouldn’t be reading Frankenstein aloud if she hadn’t asked him ergo he wouldn’t be gloomy either). The fragility of the ‘barely beating hearts’ is palpable, as is the almost impatient dismissal of the supposed solution of the volta in kick-starting or surprising the reader or the kids. It’s not that Lowe worries of herself being the oppression in their lives, but her concern that that oppression is there at all is at times unbearably felt. This is in part because the kids betoken the ghosts of others, as starkly put in ‘The Unretained’\;

What happened in the end to Luke? So clever,

xxso always utterly stoned he walked like weights

xxxxwere in his trainers, until his massive ‘biftas’

xxxxxxput voices in his head that made him late,

xxxxxxxxthen didn’t let him out at all. […]

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxAnd Martha,

xxxxxxfive-months-pregnant, quitting for her boyfriend

xxxxand a flat, my cautions drifting off her

xxlike confetti as she strutted through the gates?

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx‘The Unretained’

The powerlessness is clear in the importance of the shifting, almost spiraling shape of the poem, and a panicked sense of the control so easily applied in the classroom that evaporates once the bell has rung reads as a hair-shirt of its own.

One of the effects of the sonnet form on Lowe’s voice is a deepening of tone in this voice. Not because of any grand tradition of the form or academic nous thereto, but from the awakening, spurred voice of the Prologue poem to the concerns of those above these reflections and anxieties ring out in a tone sometimes psalmic, sometimes lamenting.

The second section of the book goes back to the poet herself as kid, as though the concerns and anxieties pouring over those kids in the first half have washed Lowe back to first principles. The dangers are more defined, here, the weapons to fight back more vital, as the second half of ‘Blocks’ makes clear

In that house of risk – unstable, unwell –

where often I was thrown like a paper jet

downstairs and hit the hard floor of the hall,

sprawled useless as a crumbled alphabet,

those drawings mattered. That name I wrote for myself,

over and over, standing up for itself.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx‘Blocks’

The dislocated identity between the thrown kid and the name on the paper (‘itself’), with the latter able to resist when the kid cannot, is sharply captured by the image of the paper jet thrown, just as ‘hit the hard floor of the hall’ hammers home the impact described in a piece of rhythm inescapable once said aloud.

Looming in this second half is ‘The Stroke’, the only poem in the book to go over the page, consisting of ten sonnet-stanzas employing both slant and straight rhyme, often over the same two lines. It is not the heart of the book – either spatially or in subject – but it strikes a jarringly (in the best way) halfway note, in this poem mainly concerned with an afflicted adult, surrounded by adults, but told through the eyes of someone unsure if they are young still, or if this is when the change occurs:

I didn’t go. Until I did. Some arrangement

for dad to drive and pick me up one night.

By the sign for Upney Tube, gas-blue fluorescent,

I waited, waited, until an hour late,

I dialled home in the blunt and pissy light

of the payphone on the hill, that slope between

the streets where I grew up, and the A13

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx‘The Stroke’

While the poet will later admit to being ‘teacher, now, and mother’ as she cooks and cleans for her parents, it is in this stanza where the kid and grown-up collide; that brilliant fac-off between ‘blunt’ and ‘pissy’, or the differences in asphalt between ‘streets’ and ‘the A13’. Here two schools of description and ages stare each other down, and the rest of the poem’s lucidly curated dreads and realities emerge from the conflicted space between.

The book’s final third is freer of anxiety and concern (though not entirely), which surprises given that it is mainly concerned with the poet’s own kid, ‘My Rory’. Crucially, Lowe does not present this third and these poems about her son as a fix-all to the fears earlier spoken of and felt, but instead manages to convey a wonderfully new strain of both fearful joy and joyful fearfulness. The tension in these poems is adroitly balanced:

My Rory wants to scoot on his own, dammit,

to soar one-footed down the street – who cares

about red lights or buses or reckless cars?

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx‘Scooting’

While the rest of the poem envisages the small scooterer as menace to car and driver alike (ending with an image too cheering and fun to extract – read the poem), the slight freneticism in the ‘who cares…’ here lays just that right amount of parental worry, turned to wonder at the confident desires of the kid.

If I sensed a wakening, a starting, in the Prologue at the book’s beginning, there are new beginnings and departures in this final section, too. The poet’s concern, again, about the kids she taught, has even widened when she realizes how close they were to stopping being kids:

But the kids I taught, who came to me at the edge

of childhood – was it really, then, too late?

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx‘Balloons’

That ‘edge of childhood’ reads as much about the teacher as about her pupils, and the sense of the liminal is weighted elsewhere, too:

He’ll pick them up next week. Then I’ll spread

my books across, full up the empty shelves,

the way for eight months now I’ve stretched myself

across the new terrain of this huge white bed.

I stay up reading late – poems, poems.

Then in the dim gold light, I write about him.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx‘His Books’

The ‘new terrain’ and the ‘dim gold light’ meet as watersheds and exploration, but firmly in the poet’s grasp, in the way that earlier in the book the young, the novel and the unexpected were equally beyond their control. The section, and the book, end seemingly in a reply to the opening ‘My father was dead’:

But I’m not a master, just a pair of palms

which push or pull or loosen someone’s lines –

I still need kind and guiding hands on mine.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx‘Kathy, Carla’

By the end of The Kids, this reader takes issue with that denial: Hannah Lowe is a master, and this is a book of mastery. Trust The Kids.

Patrick Davidson Roberts was born in 1987 and grew up in Sunderland and Durham. His debut collection The Mains was released in 2018 and he co-founded Offord Road Books in 2017. His poetry has been published in Magma, Ambit, The Dark Horse, The Rialto and on Wild Court and he reviews for The Poetry School.

5

Annemarie Austin’s Shall We Go? reviewed by Kathleen Bell

Shall We Go? by Annemarie Austin. £9.95. Bloodaxe. ISBN 978 1 78037 553 3

Annemarie Austin’s poem ‘Hole’, which comes half-way through her new collection, consists of just seven short lines:

A hole is defined

solely by what it is not.

The cave is a kind of

out of.

xxxxxxxBut no one

would have come

for just the cliff.

Like many of Austin’s poems this draws attention to something that resists easy definition. She is concerned with things that are hard or impossible to see, and objects and places that are either boundary-less, like an unframed picture, or whose boundaries, like the sea, change moment by moment. Even when she writes of something apparently static, like a photograph, what interests her most seems to be that which is hard to discern or which cannot be fully captured. In ‘The Misses Booth Photographed by Camile Silvy’ images of obscurity abound: ‘the mirror tipping its liquid darkness out’, ‘dark … seeping between my neck and earring’, the sweet ‘darkness on my cheek’. combined with hidden hands and a voice which is ‘difficult to hear.’ In this context even ‘the enormous plainness” of a crinoline seems to be part of a concealment adopted by both photographer and models.

Similarly the poem ‘Nijinsky Jumps’, based on an asylum photograph of the dancer aged 51, notes what cannot be seen:

one hand is a blur like a bird

up too quick for the shutter speed.

The other hand is lost in his double

shadow.

This leads to a contemplation, in parenthesis, of how shadow complicates what we see. The poem refers first to an antique image of a Chinese execution in which a beheaded man’s shadow stays intact in the moment after the beheading, and then to Nijinsky’s shadow, cruciform on the wall behind him as he is captured mid-jump. Instead of dwelling on the present bleakness of the great dancer, confined, ‘obedient / but not emotionally involved’ the poem relates the captured moment of Nijinsky’s jump to a millennium-old ivory carving of Christ on the cross. Thus, in the photograph, Nijinsky also hangs forever ‘in a lonely place’..

Other poems too indicate multiple ways of seeing. At its simplest, in ‘Fruit,’ what appears at first to be a tiny berry is revealed as

a snail on a single thread

of spider silk

fixed by a bubble

of snail spit

or by the spider’s artifice.

Even with the precise observation which draws us nearer to the snail the poet be certain what is being observed – is the snail attached by its own action or is it the spider’s prisoner? Either way, the conclusion leads from the apparent promise of letting the daylight through as the snail rocks to the snail’s ‘dark small self’ inside its shell ‘shrinking back and back / very far indeed.’

Elsewhere both boundary and blurring seem like threats. In ‘Problem,’ the epigraph from Henri Bergson suggests that what is being investigated is a philosophical difficulty caused when ‘we separate out in space phenomena which do not occupy space.’ But the poem that follows takes a woman as the problem: a woman who is ‘not the one’ but who has to be put ‘somewhere she can’t / bump up against the rest whoever // they might be.’ But when separated from any background she herself becomes a place to explore in a discomfiting way: ‘her arms and leg bones pathways / and they come and go through her.’ Eventually her identity is disturbingly merged with or blurred into that of a house:

The grain of the floorboard

is growing through her cheek

her ear its imitation. She can hear

the knives in the drawer

the door remaining closed. Her mouth

is open as the window in the

gable end mortared with all

her hair stirred into the mixture.

Equally disturbing is the poem that follows, ‘Polly Vaughan – Variations.’ Taking a folk song as its starting point the poem offers three versions of the killing of Polly Vaughan by her lover, who, according to the song, mistook her for a swan,. The variations on the original story disconcert. The first, apparently in the voice of the lover, suggests that the young woman had ‘wrapped her head and her neck and / her shoulders in white laundry’, but the repetition of ‘and’ coupled with the seeming unlikeliness of wrapping a head in laundry, destabilises his account, as does his reminder that ‘Polly Vaughan rhymes with swan / and covered head rhymes with dead’. In the second variation another voice declares that ‘She wanted to be unseen / and no one saw her / for herself’ while the third variation offers a magical interpretation to explain the killing:

Some women like Polly Vaughan

transform at night to creatures

Customarily when darkness fell

she was swan on the black pond’

But what all three variations hint is that, according to those who speak of the event, a young woman, intentionally or not, brought her death by shooting upon herself. It is for the reader to note inconsistencies and improbabilities but though we may suspect we are merely the readers and cannot, even in this imagined world, be entirely sure of anything.

Perhaps the poem that most represents Annemarie Austin’s way of seeing and the connections she makes is ‘Cut Out’, in which a piece of corrugated cardboard reminds the poet of seeing a queen’s tomb on which the face was too high to be seen but the visitor could observe instead:

the stone petticoat

edges, winding in and out and

crowding with convolution

that space between

Once more there is a characteristic concern both absence and presence, the seen and unseen, as the poet recalls ‘the pleating / of air and darkness’ which indicate both complexity and depth.

Again and again Austin’s poems lead us towards the unknown. They drop hints but refuse to offer a solution to what we can’t quite see and can never fully understand.

Kathleen Bell is a poet and fiction writer from the East Midlands. Her most recent publications are the lockdown chapbook Do You Know How Kind I Am? (Leafe Press, 2021) and the collection Disappearances (Shoestring, 2021).

*****

Tishani Doshi’s A God at the Door reviewed by Rona Fitzgerald

A God at the Door by Tishani Doshi. £10.99. Bloodaxe Books. ISBN: 978-1-78037-577-9

A God at the Door, is Tishani Doshi’s fourth collection of poetry. Doshi is of Welsh-Gujarati descent both of which she draws on for her work. She lives in Tamil Nadu. This collection is brave, brilliant and undaunted. It’s brave because Doshi writes about what is happening in India under the BJP and Narenda Modi from the response to protesters in Delhi to the story of a young woman walking home hundreds of miles during the Covid lockdown. It’s brilliant because the poems are tender and insightful, capturing so much inhumanity and inequality in a strong modern voice. The poems are woven like silk tread yet as sharp as a rock face. And, the collection is undaunted because Doshi tells the truth about pain, suffering inhumanity, hurt, imperfection and inequality.

Doshi’s voice is direct as she engages the reader using phrases like imagine or say – we feel invited in to her deliberations, her journey. And, while she addresses issues of searing emotional and physical pain, her voice is never judgemental. She remains matter of fact. Doshi’s skill is that she maintains distance for us and for her as the author. While there is a tension in many of the poems between conflict and renewal between despair and hope, Doshi engenders a fellowship. She manages to describe harsh reality along with offering comfort and solace.

Like many others, I came to Tishani Doshi’s poetry through her poem: ‘Girls are Coming out of the Woods.’ This poem has such resonance with me as an Irish woman facing up to the inhumanity in Ireland’s treatment of women and girls. In particular the undervaluing of females and the privileged position of males. For me as a woman, someone who has worked on politics and public policy for years and as a novice poet, this collection is wonderful, expressive and skilful. It encourages me to be more daring as a poet.

Many of the poems come back to what is happening in India – the need for purity and the sharp rise of Hindu nationalism. From the alphabetical acrostic ‘Creation Abecedarian’ written in response to the Indian minister of higher education saying that Darwin was wrong, that Indians are the descendants of sages, to ‘The Storm Troopers of my Country’. In The Stormtroopers of my Country, Doshi articulates what is happening with clarity and daring:

‘The stormtroopers of my country love

their wives but are okay to burn

what needs to be burnt for the good

of the republic often doing so in brown

pleated shirts and cute black hats with sticks…’

The poems are wide-ranging both in themes and geographically. While many reflect her views as a woman living in India, they touch on happenings in Kabul, Manchuria and the Philippines. If the poems have a world view, it is through the lens of shared humanity in particular Doshi’s experience of being a woman. ‘In Every Unbearable Thing’ we are invited to a journey through the life of woman:

‘say you begin as rib or clod

of earth say you are blossoming

until someone stares too long

at your shirt and leaned in

unbuttoned pushed forced

don’t mistake me this is not

a poem against longing

but against the kind of one-way

desire that herds you into a

dead- end alley and how this can

lead to a weakened epidermis

and despair and nights of howling

and who can you tell except

mother friend cat

while sky keeps on being sky

and street fills with danger’

Phrases like ‘cauldrons of hurt’ capture so much of women’s experience, the fact that for women there are perils in so many places and spaces as well as in so many different situations. All of the stories in the poems are written with skill, rhythm, beauty and energy. I wasn’t surprised to learn that Doshi is a dancer. Her poems swirl and surround me like Shiva’s many arms disrupting space and time. They are an incantation, neither judgemental nor despairing allowing a shaft of light into our responses. As if, by the naming of things, they are rendered bearable.

Notable in the collection are the titles of the poems. Who would have expected a poem about Pliny the Elder and mansplaining? In an interview with the Hindustan Times, Doshi described them as a step ladder into the poems. The titles draw us in as we try to imagine how the poems will flow. Not only to the titles offer the architecture of a poem but many are playful; ‘The Comeback of Speedos’ or ‘Why the Brazilian Butt Lift Won’t Save Us’ and as already mentioned ‘Advice for Pliny the Elder, Big Daddy of Mansplainers’.

Alongside the invitation in the various titles is Doshi’s use of form. She takes risks across the page as well as using playful shapes to frame the poems, often while addressing serious issues. The poem ‘I Carry my Uterus in a Small Suitcase’ is artfully arranged to illustrate the shape:

I carry my uterus in a small suitcase

for the day I need to leave it

at the railway station

Till then I hold on

to my hysteria

and take my

nettle tea

with

gin.

The arresting titles, form and content allow a us a way into each poem. Her word choices and poetic daring – notably rhythm – carry us through. Each time I come back to the poems, I’m refreshed, enthused and charmed that her words can connect us with such sorrow yet offer such solace. The final poem ‘Survival’, Doshi acknowledges that ‘Hope is a noose around my neck.’ With all that she has shared with us, we know she endures because she writes, she dances, she mourns and rejoices in our humanity and frailty. Highly recommended.

Rona Fitzgerald was born in Dublin; she now lives in Glasgow. She has been a lecturer and a researcher in various Universities in Ireland and the UK. She began wiring poetry in 2011 and has had poems pub lished in The Stinging Fly, Oxford Poetry , the Blue Nib Magazine, Dreich Littoral Magazine and many others.

*****

Myra Schneider’s Siege and Symphony reviewed by Ruth Sharman

Siege and Symphony by Myra Schneider. £9.95. Second Light Publications. ISBN: 978-0992708849

Myra Schneider already has fifteen collections of poetry to her name (plus several prose works and collaborations) and the poetry is still flowing as easily and fluently as it ever did, coloured by a fierce optimism and a joyful engagement with life. Such optimism and joy may not necessarily be “fashionable”, but Schneider is less interested in poetic fashions than speaking her own truth.

Central to this new collection is her preoccupation with the plight of our natural world, as the dedication “For Planet Earth” makes abundantly clear. What is also clear is Schneider’s refusal to despair. The poems, like the poet herself, are driven by an unstoppable energy. Although her body is “past its best” and she dare not risk a walk in the snow (“Today”), she finds another way to replenish her store of inner wonders by taking a virtual walk to the orchid house at Kew. And the tree that has been cut down, the stump set on fire, in “Resurgence” (the title says it all) is still putting out buds, prompting the poet to declare herself “moved by the resolve to live in this world”. Everywhere she finds evidence of this will to survive – in the butterfly that flies thousands of miles, navigating “as precisely / as an electronic system”, the seedling that “thrusts into a world of blue and green music”, the tomato plant that sprouts through the vent in a drainpipe…

And the miracles of nature give way to poetic miracles in a poem such as “Like Small Wishes” where the flight of four orange-tip butterflies drifting across a traffic-filled road takes us into a scene as surreal and unexpected as the vision of Stanley Spencer’s “newly-awakened dead emerging from swung-open tombs” – a kind of earthly paradise where the metal bodywork of cars morphs into butterfly wings, “tapestries of dusk and orange”, concrete frontages are crammed with flowers, “in a song of praise”, and the person to whom the poem is dedicated floats into the sky revelling in her newfound weightlessness.

These poems are a celebration, but they are also a call to arms. The insistence of the natural world is matched by Schneider’s own insistence that we need to act. She speaks plainly where plain speaking is required: of the distance-defying monarch butterfly in “Flying” she asks: “do we have the will, / the wit, to stop destroying its world, our world?” And the poem “Becoming Plastic” opens with that familiar experience of battling with plastic packaging – packaging which fits like a skin, “as smoothly as a seal’s” she notes, neatly introducing one of the ocean’s many casualties. Everything comes “cosied in plastic”, “swaddled”, even – in the poet’s dream – the baby extracted by the midwife from its mother’s womb, leaving us with visions of something akin to a shrink-wrapped chicken on a supermarket shelf. Conversely, the wind turbines in “Wind Farms” are described as if they were lovely living creatures:

…a ghostly species

tall as lookout towers, graceful

as long-necked cranes, grazing in silence

“Praise be for these magnificent birds,” the poet continues, in language that has a near-biblical ring:

let them inhabit sea, island and ocean,

let them multiply on hilltops and thrive in deserts…

That so many poems in the second and third sections of the book are a response to painterly, or other visual, stimuli is unsurprising for a poet so obviously in love with colour and light. A whole range of painters provide her with inspiration, from Hokusai to Van Gogh and Henry Moore to the exuberant Marianne North, surely a kindred spirit. Memory serves as another prompt and we have poems here recalling the moment when words in a book first started to make sense, recalling the beloved landscapes of childhood “where clock time is meaningless”, the exhilaration of gliding on a bicycle over the South Downs, gazing down on “the world’s quilt of mustards / and greens, its toy sheep, scribbled hedges…”. The last two stanzas of “Cropthorne Church”, meanwhile, sum up the poet’s credo and are worth quoting in full:

But why am I here? I’m not a Christian. My belief

is in the force which rolls through all things:

the light still reaching us from the early universe,

darkness splitting apart to let morning be born,

rain filling puddle and sea, the will to survive stored

in ovaries, love, minds mastering the beauty

of mathematics, this poignant arch which rises

in the silence beyond the leaning walls of the nave.

She mentions “love” here, and many poems testify to the poet’s natural empathy, her generous wish to inhabit – however briefly – the lives and experiences of other human beings. She ponders on the “real Mrs Beaton”, her private sufferings totally obscured by the public persona, and wonders about the three women staring at the ocean in Peggy Somerville’s painting. What are they really thinking and feeling, these women who “only exchange nothings without a whisper / of selves”? She grieves for a dead friend whose fluency with words barely extended to expressing her own feelings and speaks for the voiceless, shadowy women of the past, those “secondary” figures.

The homeless too are in a sense “secondary” and the focus of several moving poems at the end of section three, while section four represents a sustained effort to enter the lives of others, making absolute sense – emotionally speaking – in terms of all that precedes it. This one long poem gives its title to the collection as a whole and draws on carefully researched material relating to the siege of Leningrad during World War II and the composition – and performance by an enfeebled scratch orchestra – of Dmitri Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony, the “Leningrad” symphony. Schneider skilfully interweaves what read like journal entries juxtaposing contemporary London with early-1940s Leningrad, bridging the gap between her own life and the lives of those living through the siege, Shostakovich himself of course but also the likes of Persian scholar Aleksandr Boldyrev who “sorts the shrinking stock /of furniture and his books into: keep; sell; burn” and the schoolgirl Lena Mukhina with her typical teenager hopes and dreams, who notes in one desperate diary entry: “Mama died / last night, I am alone.”

Siege and Symphony is a collection of great humanity and commitment. An earlier poem, the curious and beautiful “Dredging the Moon from the Bottom of the Sea”, can be seen as a metaphor for the processes at work throughout this book – the salvaging of beauty and wonder in the face of crisis and threat. The poem, we are told, references an exercise in the ancient Chinese practice of qigong and this is how it concludes:

You will find the moon, small as a child’s ball.

Gather it in your arms, lift it gently to the surface

and watch it lay a silver path. Now raise it

above your head and in the sky a silvery queen

will emerge from the swirling cloud layers.

She’ll reflect on herself in muddy puddles, conjure up

streams of glinting eels in rivers and summon

passageways through every darkness.

Ruth Sharman lives in Bath and works as a freelance translator from French. She has published two poetry collections – Birth of the Owl Butterflies (Picador) and Scarlet Tiger (winner of Templar’s Straid Collection Award for 2016. Rain Tree, due out from Templar in 2022, charts the poet’s attempts to reconnect with the India of her childhood.

*****

Anne Ryland’s Unruled Journal reviedwed by Pippa Little

Unruled Journal by Anne Ryland. £10.99 Valley Press ISBN: 978-1912436620

The deeply textured painting on the cover of Unruled Journal sets the mood and tone for all that lies within. A fishing boat’s prow rests at the sea’s edge in blue light which might be early morning or early evening, just before or just after a storm…the mysterious depth of the image draws you inside and then you meet the blues and salts of Ryland’s voice, the many layers of her poetic imagination.

This is a third collection, assured, wide-ranging, whose themes work subtly together to deepen and expand its concerns. I was struck by Ryland’s ability to evoke quite desperate situations (such as disability, ill health, death of parents) with a deceptive lightness and grace: grief and loss are met clear-sightedly, even made beautiful. I love how Anne Ryland’s voice can span ranges of feeling in a single poem, embracing gravity along with a deliciously strange wryness. One of my favourite poems, ‘The Finishing Work’ does just this, superbly.

Several of the poems are informed by Ryland’s work as a German scholar and translator having lived and studied in Germany. Her interest in the war and its aftermath for that country has led to ‘versions’ rather than translations of poems by a little-known Jewish poet from Cologne, Hilde Domin (1909 -2006) . These include stark, arresting lines: ‘I am homesick for a country/where I have never been’…’I throw my keys into the sea/on boarding the boat’ (‘The Word of the Clouds’). Other poems such as ‘Trummerfrau’ (about women who cleared rubble from German cities) and ‘Helga and the Handcart’ explore issues of homelessness and seeking of asylum, issues as pressing today in a different yet related context: refugees for whom ‘home’ has ceased to exist. She also works from two poems by the Polish poet Leon Zladislaw Stroinski, who died in 1944, to create the spare and very moving ‘Warsaw’ and ‘Year 1944’. While Ryland is to be commended for bringing to wider attention yet another uncelebrated woman poet and an ‘obscure’ war poet, these choices say something about her wide ranging sensibility. She is more than a ‘local’ or ‘regional’ poet.

Localities thread through the collection, though. She was at sixteen ready ‘to scramble out of East Saxon land – Essex -‘ to journey into Germany with a blue suitcase and eventually, to write from her settling-place close to the England/Scotland border. The final sentence of the last piece is: ‘Running, I become the border’. In many ways I think this book is an assertion that after a long, difficult and painful process of moving between different physical and imaginative spaces the poet has made it through: she has assimilated some of the contradictions and limitations she has experienced: through her newly freed, running, supple body the ‘border’ is now lithe, alive, some contradictions synthesized: in middle age possibilities open, expand.

The poignancy of this ability to move, to go exactly where the poetry wants, comes partly from other poems earlier in the collection about the poet’s mother and aunts’ disabilities. My absolute favourite poem of all here is ‘Poppy Run’, where the ‘I’ is running ‘faster than my muscles/and bones have given me permission’, and remembering ‘the sisters unable to walk or wave goodbye’ but who ‘shooed their daughters out/into the world’. It goes on:

‘The anguish of leaving a mother stranded,

the yearning to be gone.

The contract, the stretch.

The keeping going while breaking down –

doggedness, wrought into dignity.’

and concludes:

‘as I pass and pass –

this lifelong overtaking.’

The family past also echoes: in one poem, ‘A Daughter Returns’, Ryland goes back to the small Scots town where her mother was a baby and in ‘Before the Pencil-trail Disappears’ she over-writes the fading script of a letter from her grandmother to her daughter. Letters are a recurring theme, from the strange, unsettling ‘Letter from Uncle’ to ‘My Mother Writes a Letter’, exploring how sometimes more can be said through being unsaid, and the ways that old-fashioned ‘rules’ of letter-writing brought unsettling undertones to the seemingly ordinary.

There is a lot of joy in Unruled Journal. I loved the poems which celebrate a return in later life to the freedom and speed of running and which take the collection off into a heady new direction. I also enjoyed very much the sequence of poems about Mr Millar’s desk, with its brass plaque from 1908, bought by the poet in an auction. Ryland has a lot of fun exploring roles and gender from the starting-point of this symbol of masculine gravitas, and her relationship to it as a woman poet and its new owner. Her feminism is clever and sharp, mordant yet subtle. In a surprising twist, most of the poems in this group are in the voice of a ‘surplus woman’ from post-World War One. The desk is where she writes in her ‘unruled journal’ – without lines or paths to follow, she must make her direction by herself : ‘Now I write the heart’s path’.

This collection evokes a hard journey, unequivocally female while being at the same time vitally human, of a life working through grief and loss to emerge in a flowering. It’s a triumphant assertion of the power and range of Anne Ryland’s poetry yet it also speaks for (and to) a whole other tranche of (typically ‘invisible’) women whose later years also see this ‘coming through’, who have learned how to ‘pass and pass’ – and keep going. Ryland is an extraordinarily gifted poet who should be much better known. I recommend this book highly.

Pippa Little is a poet whose work has appeared in Poetry Review, POETRY, Magma, The Rialto and other magazines. She has a poem in the latest Bloodaxe anthology Staying Human. Her third full collection Time Begins to Hurt comes out from Arc Publications in 2022.

*****

Frank Dullaghan’s In the Coming of Winter reviewed by Janice Dempsey

In the Coming of Winter by Frank Dullaghan. £9.99. Cinnamon Press. ISBN: : 978-1788641111

The word that came to mind when I finished my first reading of ‘In the Coming of Winter’, Frank Dullaghan’s third poetry collection, was ‘fearless’. For there is fear in these poems — of the dark, of plague, of old age and the final darkness, death, but it’s fear confronted, examined and contained. A kind of fatalism sustains the poet.

But on subsequent readings, I became more aware of Dullaghan’s motive in his collection. It emerges in several of the poems as a need to ‘bear witness’. He states it clearly in the first poem: ‘Witness’, in which he sees an apparition of his dead father. Throughout the collection are poems of meditation at the transitions between night and day, on the shores of lakes. ‘Witness’ is set at dawn by a lake, peaceful at first light, but anxiety intrudes:

the sun has stalled

under a hood of cloud and the lake dulls.

And the squawking of the early birds sounds anxious.

But the ghost has nothing to say to his son; he is simply ‘there’:

the world happening as it always did

with no special purpose for him or me

or any of us, beyond bearing witness.

And in the final poem, ‘Flying South’, he sees himself

as a witness, as the swallows fly south,

of the way endings can feel like beginnings,

if you come at them from the other direction.

Between these two end-pieces, Dullaghan takes us on an emotional journey set geographically between his homeland of Ireland and the hot, far-away places where he has earned a living: two very different climates and landscapes. Above all, it’s his inner landscape that we get to know in the four sections of the collection.

The title poem of the first section, ‘Farewell Lovely Nancy’, is subtitled ‘A folksong for Covid 19 times’. He grieves:

“Farewell lovely Nancy, the world has closed its doors

and it makes no odds at all how the wind lifts and roars,

there is no going back to what we had before.”

The raw realities of life and death are revealed in a parody of a childlike rhyme:

“Love is not an answer, we’re no longer that naïve.

Death’s become a hammer and there is no reprieve.”

‘How Quickly the World can Change’, The first poem in this section, is a dream-like image: at first an idyllic scene out of a Rousseau painting, a child left unprotected surrounded by jungle creatures: “creatures and baby making a silent tableau”. But when the parent returns the dream becomes a nightmare: “The animals /watch you now: anticipation of what /will happen next ticking between them.” Human civilisation is fragile in the face of nature.

In more literal images, Dullaghan records his fears for his brothers and friends in Ireland, during the first year and more of lockdowns and restricted social activity. ‘Crossing Over’ is a bitter reflection on the loss of his brother, and on the fragility of life: he thinks of the many unpleasant ways to die “in these vicious days”:

“smothering as their lungs clog: this new,

black death which we try to lock out.

[…]

“What I have learned from my brother:

maybe in the end it’s the simplest thing—

here then not here. Over.”

Cut off from his family as he works in the far and Middle East, Dullaghan is forced to accept that his sister Mary may also die. In ‘Walking the Mile Road’ he recalls “It’s a long time now, sister, from your confirmation white” and the feelings of being “high on the innocence and zeal of our recruitment”. From the children walking optimistically towards their future, the poem moves quickly to Mary’s illness from Covid, while her brother can only call her daily, cut off from Ireland because he works abroad. Mary’s survival is expressed by another, shorter journey, from her door to the garden gate. “That is enough” he says, stoically.

‘The 2019 Coronavirus’ bears witness to the pandemic’s presence in Kuala Lumpur in February 2020, and the helpless fear that it inspired.

“…A great tempest of fear

is approaching. We will be up

to our armpits in its squall.’

This first part of the book is full of anxiety, including stress at the international political level (“In America, they are waiting for a president /to finally act like a president”) but it closes with a glimpse of personal salvation:

‘Life is filled with noise.

But there is peace

if you make space,” (‘Simply Meeting for coffee’)

‘Dingle in the Coming of Winter’, the section from which the collection’s title comes, is full of darkness and anxiety, with little to lighten it, but these are powerful poems. ‘Darkness, the opening poem, is a catechism of fear, a profile of the dark that makes it a concrete, evil, deceptive being waging a personal vendetta on mind and body. It ends with chilling lines:

The way it claims to be your mother

and you are just going home.

The prose poem ‘Hope can be a Burden’ is a monologue on ‘Another day when I’m looking out my window, shivering a little, the sky trying on its makeup’ in early morning. Financial fears that he is not being paid for his work here where “even this early, the heat is unbearable” fill his mind, interrupted by loneliness as he cannot help hearing mechanical sounds of lovemaking from the room above and “my mind wants to add small gasps, love sounds.”

This part of the book catalogues the feelings of futility that he feels at work (“Already, people have begun to look through me / I have been moved to a smaller desk that is easily passed” — ‘Transparency’) and the sense that he is struggling for equilibrium, expressed very strongly in ‘Tightrope’, a poem about a half-dreamt, half waking experience.The poem toggles between the disturbed dreamer tossing and turning in bed, and his dream:

“I hold the long pole in my hands.

It’s supposed to keep me steady. I wonder

if I should get up, read maybe. I sway …”

Another source of anxiety in this section is set out in ‘They are Running at Bullets,’ ‘Sons of Guns’ and ‘Lebanon August 2020 (for Z)’ — poems that refer to killings in Palestine, the NRA’s power to prevent gun control in America, and personal grief when Lebanon was wrecked by a bomb in 2020. But again there are poems that pinpoint a mood of hope, or at least philosophical acceptance. ‘Greyhounds’ is a memory from 2018, of a glorious day in Dubai. ‘Stunt’, another poem set at change of light, this time at dusk, accepts and looks at the fact of mortality

“There will always be a last time:

a last walk, a last meal, the burnt

hours sliding away, that sublime

self-regard tossed aside. that stunt

when you breathe and then you don’t.”

‘Dingle in the Coming of Winter’, the poem that gives this section its title, is another bright spot in the section. Seemingly written on a visit home to Ireland in 2017, this is a portrait of Ireland as a refuge for the narrator. He describes the fishing village, with loving clear-eyed detail, including “a murder of crows/revelling in their Dark Arts”, though he admits “So much of it is memory”. And

“Cold has found its way into bone.

I came here, feeling the need to drown

in the untamed weather, escape, be

In Dingle in the coming of winter, Understand

that this is just the way of things:

land trying ot outlive the sea …”