*****

The editor is grateful to Timothy Adès and all the translators who have worked with him for the commitment they have shown in producing the splendid array of work contained in the translation feature. [Ed]

*****

Editing this Supplement has been an absolute delight. Free of the economic constraints of print, so odious to editors and even more to contributors, I have been able to accept everything and exclude nothing. And with little prompting, I’ve been regaled, deluged with exciting material.

This Supplement is arranged in two parts: before and after 1900. First, something from the remote past of Arabia: English verse from French prose. Then to the nineteenth century, which still dominates our reception of French poetry, with so many great poets – among them Hugo, who in his time outweighed them all. And he noticed children: not many great poets do. Rilke leads us into the 20th century, the most widely translated modern poet from German, latterly writing in French. Devout Francis Jammes with his prodigious beard; Oscar Milosz, Lithuanian diplomat; Robert Desnos the surrealist, a Resistance martyr; a woman Marie-Claire Bancquart translated by a woman, Anna Gier, a newcomer I am proud to introduce; finally George Goddard, translating his own St Lucian Kweyol; Gilles Ortlieb; and Maram al-Masri: three poets alive and flourishing today. [TA]

*****

NB: For most of the poems included there are links to original French texts.

The Poets:

Romance of Antar and Abla • Victor Hugo • Charles Baudelaire • Arthur Rimbaud • Aloysius Bertrand • Théophile Gautier • José-Maria de Hérédia • Rainer Maria Rilke • Francis Jammes • Oscar V. de L. Milosz • Robert Desnos • Marie-Claire Bancquart • George Goddard • Gilles Ortlieb • Maram Al-Masri

Lucy Hamilton • Timothy Adès • Will Stone • Stuart Henson • David Malcolm • George Goddard • Anna Gier • Stephen Romer • Hélène Cardona

*****

PART ONE: BEFORE 1900

*****

Lucy Hamilton: From ‘The Romance of Antar and Abla’

Introduction

Antarah ibn Sheddād is the hero of one of the great pre-Islamic epics of the Arab world. Part historical and part mythical, it is the story of a black slave born to a noble Arab father and an Ethiopian slave mother, and of his long quest to achieve nobility in order to win the right to marry his beautiful cousin Abla. Although it belongs to the same tradition as The Arabian Nights, unlike that epic it was never adopted by Western literary tradition which, according to Driss Cherkaoui, is because it does not so obviously share transcultural religious or fantastical literary features. That said, it does mention several familiar biblical characters, including the Prophet Issa, Jesus.

The story of Antar and Abla takes place in Saudi Arabia and, in the great tradition of oral epic, was passed down through the generations by highly skilled and equally valued reciters, until the 8th century CE when fragments began to be written down and collated. These Arabic versions run into hundreds of volumes. My source is Le Roman D’Antar D’Après Les Anciens Textes Arabes by Gustave Rouger (L’Édition D’Art, H. Piazza, Paris 1923). In my terza rima version, I have kept to the structure of Rouger’s book, which is in three parts with five or six chapters in each part. My cantos comprise five poems of eight tercets plus a single hanging line. I have also drawn upon Driss Cherkaoui’s seminal work, Le Roman de Antar: Perspective littéraire et historique (Presence Africaine, 2001), my aim being to privilege the Arab perspective over the European.

As with Rouger’s book, my version begins with a Prologue introducing Antar as the greatest Arab warrior, whose example in the ‘time of ignorance’ paved the way for coming of the Prophet Mohammed. Canto One introduces the ancestors of the Bedouin tribe, its king and social mores, and deals with the first raid and with Antar’s birth and early childhood. In Canto Three, where this extract begins, Antar is already on his quest to win the beautiful Abla’s hand in marriage.

CANTO THREE THE POOL AT ZHAT AL ARSAD

I

Days passed. Shaddād’s uneasiness had doubled.

xxxxxHe sought his loyal brothers, Mālik and Zahmat,

xxxxxand told them he predicted tribal trouble.

They plotted to ambush Antar somewhere far,

xxxxxhis disappearance would be unobtrusive,

xxxxxthey feared that one day he might kill a Shah.

Dawn brushed the trees as, unaware of the ruse

xxxxxand dreaming of his sweetheart’s flowing locks,

xxxxxAntar departed, his mood light and effusive.

He sang as he went, driving the herds and flocks,

xxxxxpausing to find some edible thistle roots,

xxxxxsearching the sky for the trailing legs of storks.

He leaned against the tree of little fruit,

xxxxxthat stunted bush that once, in paradise,

xxxxxhad been profuse but now refused to fruit:

the Lote-tree whose cruel thorns chastise,

xxxxxthe thorns that men crushed down on Issa’s brow

xxxxxbefore he died, and blood poured in his eyes.

Now Antar found himself on treacherous ground:

xxxxxthe desolate and dangerous Valley of Lions.

xxxxxHere, the schemers lay hidden behind a mound,

and here, on land a wilderness for aeons,

xxxxxthey waited to kill Antar, to leave no trace.

xxxxxThey didn’t know their scent had drawn a lion,

that stalking through the grass it crept apace.

II

When Antar saw the lion his muscles flexed,

xxxxxhot-headed and impatient for the tackle

xxxxxhe sang as he leapt into action as if by reflex:

O lion, O father of lion-cubs, O jackal

xxxxxof the sands, O king of lionesses, welcome!

xxxxxSo strong and proud, how great will be your fall.

Prepare to meet your doom, to be undone.

xxxxxBut I’ll not end your days by sword or hatchet:

xxxxxyou’ll drink the drop of death by my hand alone.

For, of us two, I am the lion in combat.

xxxxxO watch me throw away my man-made weapon!

xxxxxObserve my open hands, O dog of the desert!

Bare-handed he advanced towards the lion

xxxxxwhich growled and opened up a cavernous mouth

xxxxxthat he’d no intent, far less desire, to lie in.

He ripped its jaws in two to north and south

xxxxxwith a terrible cry that echoed round the gully ―

xxxxxan awesome feat for such a tender youth ―

and then he slit the beast’s soft underbelly

xxxxxand skinned and chopped the body into bits.

xxxxxThe conspirers felt ― on smelling smoke in the valley ―

loath to end up where he roasted it,

xxxxxand so the three, discussing the events,

xxxxxwithdrew, and in plainly disconcerted spirits

set off again on the long trek back to the tents.

III

When rumour of this exploit reached the king,

xxxxxwho wanted to lead his men against the Tamim,

xxxxxhe placed the camp under Antar’s protective wing.

Soon Antar heard of the women’s audacious plan

xxxxxand knew it was Shaddād’s wife who proposed

xxxxxto take a feast some distance from the camp.

Although unwise, he didn’t dare oppose her

xxxxxor the eager girls. Moreover, how could he

xxxxxresist the chance to gaze upon his Rose?

Springtime! and a rich variety

xxxxxof flowers clothed the hillside in a vivid

xxxxxtopcoat for as far as the eye could see:

white and yellow marguerites, blue orchids

xxxxxin contorted shapes, violet irises

xxxxxand perfumed tubers, acerbic and acrid,

weaving their arabesques. Here ilex trees

xxxxxleaned and dipped their broad leaves into the water

xxxxxof the Zhat al Arsad pool. And in the breeze

all the young girls and women, all the daughters

xxxxxof the tribe adorned in their best ornaments

festooned the banks, blooming like living borders.

Though Antar was abstemious and attentive,

xxxxxas Abla danced, he glimpsed her unveiled breast

xxxxxand didn’t expect, in all his ravishment,

some seventy warriors swarming down the hillcrest.

IV

The Qahtan cavaliers, in coats of mail,

xxxxxswooped down on the easy prey of girls and women

xxxxxand scooped them up despite their frenzied wails.

When Antar heard his Abla calling him

xxxxxas she was snatched and thrown across the saddle

xxxxxof one of the ferocious-looking men,

he leapt like a panther, leaving the man unsaddled:

xxxxxdead of a broken neck. He killed or maimed

xxxxxsome thirty men and thirty more skedaddled.

Now Antar rushed to Abla where the women

xxxxxwere helping to revive her. Tears of relief

xxxxxand gratitude fell wet on their cheeks like rain.

Sumayya, though, had reason to believe

xxxxxher husband would blame her, and so she made

xxxxxhis son vow that he’d not inform the chief.

Not one of the men returning from the raid

xxxxxobserved the equine imposters. The following day,

xxxxxShaddād went to the pastures and was amazed

to witness Antar on a pedigree

xxxxxof great distinction, and many other horses

xxxxxhe didn’t recognise, of equal beauty.

Shaddād now questioned his son, who lied in the cause

xxxxxof duty: maintaining that the noble mares

xxxxxhad wandered off and lost their caravan’s course.

Shaddād was not deceived. Nor Antar spared.

V

Shaddād thrashed Antar with a grim abandon

xxxxxuntil, to his surprise, his wife cried out

xxxxxand shielded Antar with her arms and hands.

‘Enough! Enough! O stop Shaddād!’ she shouted.

xxxxx‘Don’t punish the lad. O Antar is not guilty.

xxxxxAllow me to explain how this came about.’

Shaddād let go his whip. ‘You puzzle me,

xxxxxSumayya. Why do you now defend this slave

xxxxxwhen you once hated him so vehemently?’

And in a broken voice Summaya conveyed

xxxxxthe tale. The boy was clearly diplomatic,

xxxxxhad acted honourably: Shaddād forgave him.

One night, the king’s sons feasted. The wine and liquor

xxxxxwere taking effect and loosening their tongues,

xxxxxand Antar soon was summoned by Prince Mālik

to entertain them with his verse and songs.

xxxxxJust then, and from a cloud of dust, a hundred

xxxxxQahtan warriors charged and set among

the sluggish men who were as good as dead

xxxxxbut for Antar’s instant intervention,

xxxxxwhich turned the tables: the Qahtan fell or fled.

The king was quick to show appreciation:

xxxxxa gold-stitched tunic, a sword of quality

xxxxxand a horse rewarded Antar’s dedication.

Henceforth he’d raid with the king’s own cavalry.

* * *

Victor Hugo: Eleven Poems of Childhood translated by Timothy Adès

These poems are as presented in the Gallimard Jeunesse series:

some are extracts of longer poems.

From MY GOODBYES TO CHILDHOOD

I have such pleasant memories

Of when we twisted, thoroughly,

Our hankies into implements

Hardened for war and self-defence,

Took apples off the local trees,

And fired our massed artillery…

And there were dodgy rungs we climbed

With Roman pride, or twice as much:

What was that citadel we stormed?

The old neglected rabbit-hutch!

GRANDMA SPINS THREAD

Grandma spins thread. The little girl

Fancies a distaff for her doll.

Grandma nods off. Quick! Get a strand,

Creep up behind…

Tease one aside!

She parts a thread from all the rest,

The spindle twizzles to unwind,

She runs off chortling, in her hand

The golden wool, the saffron-dyed.

She’s like a bird that builds a nest.

THE CHILDREN

Four jolly children pull my jacket,

Muddle my papers, make a racket.

Sundays, I work! – It’s all the same

To them: they leap and shout my name,

They stop me writing, hide my pen,

Crouch down behind the sofa, then

In turn, with mirth uproarious

Leap up – rapscallions on the loose –

Wearing a gaudy striped burnoose.

From LIFE OUTDOORS

I sit, and they come – they know I share

Their taste for butterflies, flowers, fresh air

And animals scurrying everywhere.

They know I’m a person who’s fond of them,

They can play near me, shout and scream,

And ages ago I laughed the same:

And I laugh and I smile at them today,

Though I’m sadder now, as I watch them play.

I’m always fun and I’m never fractious,

Make cardboard models and pen-and-ink sketches:

They say so: and when we light the light,

I tell them stories that scare them at night:

I’m gentle and modest, and erudite.

They see me, and ‘Look! He’s there!’ – they’ve downed

Their toys, they run to me, they surround!

Wide eyes, so fearless and friendly too:

Such heavenly eyes, they must be blue!

Little ones climb on my knees, they’re bold;

Big ones look solemn, being so old.

They bring me a borrowed blackbird’s nest,

With scrapbooks and crayons, France’s best…

I’VE ALWAYS LOVED

I’ve always loved winged creatures.

A child among the trees,

I took the little fledglings

And built them homes of reeds.

I reared them in the mosses,

And when I opened wide,

They flew, and came when called for,

Or simply stayed inside.

I loved a lovely dove, yes,

We two were lovey-doveys!

In be-my-friend behaviours,

Believe me, I’m no novice.

From SPRING MEMORIES

In the dew she ran noiseless,

Not to wake me from night:

I opened no glass, lest

She start and take flight.

Pure dawn! My sons’ laughter,

Cool cradles and harmony,

My children and Nature,

The birds and my family.

My cough would embolden!

Light step, but grave airs:

She’d tell me “The children

Are playing downstairs.”

Contented or troubled,

My heart was my fay’s,

Well-coiffed or dishevelled,

Lodestar of my gaze.

We played until sunset:

Sweet sport, charming chatter!

At dusk she, the eldest,

Would tell me, “Come, father:

“We’ll bring up your chair, you

Can tell us a story”

Their eyes were ethereal,

A radiant glory.

So I’d make up a romance

Of mayhem and murders,

Found heroes and humans

In the ceiling’s deep shadows.

Four darlings, they snorted

With mirth at the joke:

Big dunderheads, thwarted

By quick little folk!

I’M A LOVE-CRAZED CLOT

I’m a love-crazed clot.

Hey, Grandpa!

What?

I want to go!

To go? Where to?

Somewhere.

Somewhere?

Right.

Anywhere!

Just not stay here.

We won’t stay here.

Hey, Grandpa!

What?

There might be rain.

I do hope not.

I want some rain.

Some rain? For what?

To help my beans

grow in my plot.

God makes the rain.

Well then, I want

God to make rain.

You want! You want!

Grandpa?

Yes, what?

You see this toy:

I could destroy

it if I want

and God just can’t

stop me, he can’t!

He just cannot!

All right, don’t shout.

I didn’t shout –

I just want rain.

All right, you’re right.

So will it rain?

Yes, here’s the can:

It’s Mr Green’s,

Who sows and grows.

We’ll make it rain.

Where?

On your beans

And on your plot.

Hey, Grandpa!

What?

SONG

Naughty things we used to say!

Dotty things we used to do!

Loud our voices pealed.

Now, what dotty things we say!

Now, what naughty things we do!

Now, our lips are sealed.

CHANSON

Dieu, que de bêtises nous dîmes !

Dieu, que des sottises nous fîmes!

Comme on chantait !

Maintenant on dit des sottises ;

Maintenant on fait des bêtises ;

Et l’on se tait.

KING CLOGKICKS

King Clogkicks was a hunter,

On stilts he hunted crows.

He charged for walking under

Two euros, through the nose.

Quand on passait dessous

On luit payait deux sous

LE ROI COUPDESABOT

Le Roi Coupdesabot

À la chasse aux corbeaux

Monté sur des échasses.

Quand on passait dessous

On luit payait deux sous

SONG from Les Misérables

The moon’s up, dearest,

Let’s go to the forest,

Said Lenny to Lou.

ton ton for Kensington

I haven’t a thing

just God and a king,

one sou and one shoe.

Sun’s high. Sparrows two

Swig thyme, quaff dew:

Squiffy-poo.

zee zee for Chelsea

I haven’t a thing

just God and a king,

one sou and one shoe.

Two wolf-cubs quaffed,

Like throstles, oh! so blotto:

A tiger laughed,

Tittered a lot in his grotto.

don don for Wimbledon

I haven’t a thing

just God and a king,

one sou and one shoe.

He swore, she cursed.

Let’s go to the forest,

Said Lenny to Lou.

bam bam for West Ham

I haven’t a thing

just God and a king,

one sou and one shoe.

THE FAIRY

Pretty child, I am the Fay,

Yes, the Fairy. Come and play!

Where’s my kingdom? Where the sun,

Razzle-dazzle vermilion,

Bathes in warm waves’ ocean swell.

Western folk all love me well.

Mists of gold adorn their sky,

When I brush them, passing by:

Queen of lazy shadows, I

Build my magic mansions high

In the clouds of Westering.

Blue and lucent is my wing;

When I swoop and soar, my charms

Fascinate the Sylphs in swarms:

At my back they see, it seems,

Coruscating silver streams.

Rosy-pink, transparent and

Luminescent is my hand;

That’s my breath, the fragrant breeze,

Blown at dusk on fields and trees;

Tresses gleam, and lips beguile,

Singing, singing with a smile!

Mine are caves of cockleshells,

Leafy tents where pleasure dwells;

I am lulled in greenery,

Lulled on waters of the sea.

Follow, moon-child! I shall show

Where the clouds of heaven go,

Teach you how the waters flow.

Come, new companion, join my play!

Learn everything the songbirds say.

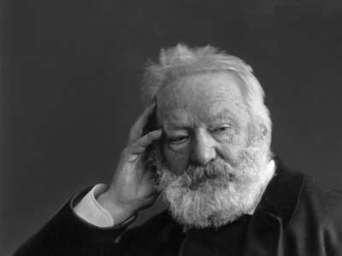

Victor Hugo 1802-85, ‘l’homme-océan’, the gigantic figure in 19th-century French literature and public life; awarded a royal pension for his youthful poems; walked between the guns in 1848, averting a massacre; plays, poetry, novels, passionate campaigns, immensely prolific; banished for opposing the coup of 1851; long years of exile in Guernsey – ‘when Liberty returns, I shall return’; huge celebrations in Paris for his 80th year; two million people at his funeral.

* * *

Charles Baudelaire: five poems translated by Will Stone

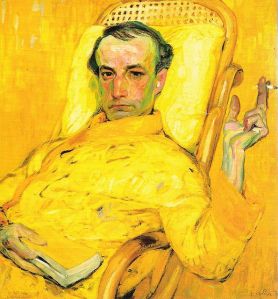

Portrait of the poet by Franz Kupka (1871 – 1957)

OBSESSION

Great forests, like cathedrals you terrify me;

You bellow like organs; and in our damned hearts,

Chambers of everlasting mourning where

Old death rattles resonate,

Replies the echo of your De Profundis.

Ocean, I hate you! Your surgings and tumult

My mind meets them within; this bitter laughter

Of beaten man laced with tears and profanities

I hear it in the vast laughter of the sea.

O’ Night! How you would please me,

Without those stars whose radiance speaks

A language I know only too well!

For I seek the void, darkness, the bare!

But shadows are themselves a canvas

Where, from my eyes, in thousands teeming

with familiar look the vanished beings.

Grands bois, vous m’effrayez comme des cathédrales

LAMENTS OF AN ICARUS

Lovers of whores are happy,

Refreshed and sated;

As for me, my arms are weary

For having embraced clouds.

And it’s thanks to those unrivalled stars,

Who blaze from the sky’s remotest depths,

That my charred eyes see nothing

But the memories of suns.

In vain I sought space,

To know its boundary and heart;

Beneath an impossible eye of fire

I feel my wings buckle then expire;

And seared by the love of beauty,

I’ll not have the sublime honour

Of lending my name to the abyss

That doubles as my tomb.

SPLEEN

Pluvius, riled by the whole city,

Tips from his urn torrents of dismal cold

Over the ghastly tenants of a nearby cemetery,

And on the fog-bound suburbs unrelenting mortality.

My cat, her mangy wasted body ever restless

Crosses the tiles to seek out a litter,

The soul of the old poet roams the gutter

With the woeful refrain of a shivering ghost.

The great bell mourns, and the smoke veiled log

Accompanies in falsetto the snivelling clock,

As from a rankly scented deck of cards,

Fatal legacy of some dropsical old crone,

The smart Jack of Hearts and Queen of Spades

Darkly debate their perished loves.

Pluviôse, irrité contre la ville entière

CONTEMPLATION

Patience, o’ my woe, and calm yourself.

You called for evening, look now, it is falling:

An obscure atmosphere enshrouds the city,

Bringing peace to some, to others worry.

Whilst the vile mass of men, cringing before

The whip of pleasure, that merciless torturer,

Harvests remorse in slavish feasts,

My sorrow, lend your hand; come with me,

Far from them. See the fallen years

Leaning from the balconies of Heaven,

In gowns of a bygone age; and regret, all smiles,

Shooting up from the fountains base;

The dying sun sinking to sleep beneath an arch,

And, like a long shroud trailing from the East,

Listen, dearest, listen for gentle night’s release.

Sois sage, ô ma Douleur, et tiens-toi plus tranquille

THE TASTE FOR OBLIVION

Downcast mind, once amorous for the struggle,

Hope, whose spur would rouse your fervour

No longer even cares to mount! Go down, without dishonour

Old horse, whose foot fails at every fence.

Resign yourself, my heart; and sleep the brute’s sleep.

Vanquished mind, laid waste! For you old marauder

Love has no more relish than a quarrel;

Farewell then, sighs of the flute and songs of brass

Pleasures, seduce no more this sombre brooding heart!

Adored spring has shed its perfume!

Minute by minute now time engulfs me

As the snowy waste a stiffening body;

From on high I contemplate the globe’s roundness

And search no more for the shelter of a hut.

O Avalanche, won’t you take me in your fall?

Charles Baudelaire (1821 1867) was a French poet, translator and critic whose reputation rests primarily on Les Fleurs du mal (1857)), arguably the most important and influential collection of poetry published in Europe during the 19th century. Baudelaire’s translations include works by Edgar Allen Poe and parts of Thomas de Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium-Eater. He also wrote prophetic essays on art, most notably ‘Salon de 1859’ and ‘Le Peintre de la vie moderne’, and important critical essays on illustrious figures such as Wagner, Hugo, Gautier, Delacroix, collected posthumously as L’Art Romantique (1869).

* * *

From The Rooftops of Paris:

Poems by Rimbaud, Bertrand, and Gautier, translated by Stuart Henson

Introduction

These versions of Nineteenth Century French poets are not presented as ‘translations’, though one or two might pass as such. They want to be living poems in English, so they’re given, now and then, to taking liberties. But they’re keen, too, to be true to their ancestors. They try to follow their forms without being hide-bound. I hope they’ll encourage readers to go back to the originals—and find in them an honest likeness.

*****

Arthur Rimbaud: five poems translated by Stuart Henson

AU CABARET-VERT

Five in the evening

For a week I’d scuffed my shoes in the rough

dust of the highways, walking to Charleroi.

At the Green Man I stopped, asked for a crust—

a ham sandwich—and a mug of Stella.

Stretched out my feet under a green table

and studied the quirks of the pub décor.

And then—almost more than I was able

to bear—the barmaid: huge tits and eyes like stars.

Well, she’d be up for it, no doubt of that!

Look when she brings my sandwich how she pouts,

as if to say I’m yours—and on a plate.

Pink ham and mustard, scented with a clove

of garlic. A frothing pint. It must be love!

Gold sun-rays glinting like the night to come.

Depuis huit jours, j’avais déchiré mes bottines

STATE OF SIEGE

The bus is trundling like some grotesque tank:

poor devil driver threading the Left Bank

bound for the Odéon, his hands frozen

livid, easing the cash-bag off his erection.

Police lurk in soft shadows while inside

the bus the honest passengers regard

the moon rocking her green bed in counter-motion.

So never mind the fragile hour, the prohibition;

relish instead lewd cries of girls with wild hair

howling like cats across the darkening square!

Le pauvre postillon, sous le dais de fer blanc

THE POOR MAN’S REVERIE

There’s a pub maybe

in some forgotten street up North

or on the rolling downs

where I could drink

and die in peace

sunk in the amber light

just nodding patiently.

So when the cash runs out

and healthcare too

it’s perfect loss—

the end of dreams.

Old rambling ghost

that washes up and taps

at the green inn’s door—

finding it shut.

MA BOHÈME

I’m stepping out, hands in my torn pockets,

(Still working the coat for that lived-in look)

Me and Calliope, riding the rocket

of imagined love, the road an open book.

Holes in my only jeans, hooking my thumbs

into my belt and steering by the stars;

singing the sky my songs, pulling out plums

of rhyme for the Pleiades, the Great Bear…

The constellations rustle when you sit alone

crouched in the verge some slow September night

and let the dew soak up and through your bones.

I’ll make my poems from the beat of headlights,

lulled like some Orpheus by the thrum of tyres,

boot-laces plucked against my heart—my lyre

Je m’en allais, les poings dans mes poches crevées

ROOKS

When winter chokes the meadows

watch them wait,

neutral as undertakers,

angels of shadow,

set to sweep in

from the skies on crepe wings.

Ice in their nests,

mud-laden brooks…

Only their dry caarks

creak round the frost’s

ramparts, sifted snow,

dull acres where they come and go.

Flocks wheel the fields of France

perch on each cross—

last season’s dead lost

in their cemeteries. Answer

the traveller then, his memory,

black acolytes of death and duty!

Or spare at least, dark saints

churched in the oaks,

songbirds and larks, shouters of hope—

for those who brace against

wood’s vacancy, horizon’s blast:

men with no future and no past.

Seigneur, quand froide est la prairie

Rimbaud’s libertine sensibility doesn’t rest comfortably in our socially correct era, though over time he has inspired some excellent re-workings. Keith Douglas’s take on ‘Au Cabaret-Vert’ (1940) is but one example. The angelot maudit who produced ‘Ma Bohème’ morphed into a scabrous satirist of establishment figures like François Coppée. ‘State of Siege’ is from the Album Zutique, parodying Coppée but signed A.R. By contrast, ‘Les Corbeaux’, on which ‘Rooks’ is based would seem to be Rimbaud at his most respectable. It was his only poem to be published in France between 1870 and 1882. Rimbaud denied having written it.

*****

Aloysius Bertrand: two poems translated by Stuart Henson

AT DUSK ON THE WATER (BERTRAND)

The coasts where Venice is Queen of the Sea… ANDRÉ CHÉNIER

A black gondola ghosting beneath the palazzos—night’s agent bent

on its mission—stiletto, lantern, cloaked by a cape.

A paramour and his lady, dabbling in love: ‘Perfume of orange-trees

and stars! And you, sweet signora , cool as that statue in the grove!’

‘And this—was that a statue’s kiss, my Giorgio, my sulky brave?

Deny it—you love me! All heaven can see past your pretence!’

A noise? Nothing. Nothing but the pluck of the waves as they rise

and fall on the steps to the Giudecca.

Then: ‘Help me! Oh, help!’ ‘Mother of god! A drowned corpse!’

‘Stand back! He has confessed.’ A monk, there suddenly at the

balustrade…

And the black gondola, sped by its oar, slipping between the

palazzos—night’s agent home from his mission; stiletto, lantern

eclipsed in his cape.

CARNIVAL NIGHT

Mask: lend me your lantern

the stars are blown out.

Mercurio: Hah! Your cat

can see by its own light.

O foolish little gutter-sprite! What made me think I’d hide tonight from the storm in a lantern that hangs at a courtesan’s gate?

At least I can laugh at the bee I hear buzzing about this luminous house, weighed down by a raindrop and trying to get out.

Bedraggled and chilled he comes begging a light for his taper to show him the way to make his escape.

Too late! Now the paper has caught and roars up in flame as a gust shakes the shop signs and batters the street.

Ah! God’s Grace! cries a nun and crosses herself as the fireball takes. Go to hell! I shout back and spit sparks in her face.

Alas for poor me! This morning I dressed like a goldfinch, a miniature doge, in his red and black vestments, his fine robes of state.

Louis ‘Aloysius’ Bertrand died in Paris in 1838 at the age of thirty-three. His fame rests on his sole publication, a book of prose-poems entitled Gaspard de la Nuit (1842). Despite his association with the Romantic movement in French poetry, his ‘fantasies’ of ‘Old Paris’, and ‘The Night and its Marvels’ appealed to Baudelaire, and provided a template ‘to apply to the description of modern life’ in Le Spleen de Paris. He was championed, too, by Mallarmé who declared him to be ‘one of our brothers’, so there’s a direct connection between Bertrand and the poésie des villes of the Symbolists—as well as the ‘art for art’s sake’ of Gautier and the visionary exuberance of Rimbaud

*****

Théophile Gautier: two poems translated by Stuart Henson

ART

Oh, yes, all the best art

resists your work.

It starts

as a solid marble block.

Its labour of despair

insists, if you can hack it,

you wear

the Muses’ tight strait-jacket.

Free verse? Why, shame on you!

That old commodious boot—

glass shoe

for every Cinderella’s foot!

Sculpture won’t work in plasticine;

soft thumbs, however much you will it,

though keen

can’t make the marks of real spirit.

Remember Michelangelo: Carrara’s

best his medium of choice,

its rare

silence shaping-out his voice.

You need the truest hand

to trace a vein of agate, follow

and find

the lost profile of Apollo

or steal from Syracuse

a bronze-age hoard

and use

it to re-cast your words.

Painter, don’t dabble water-wash,

stains of green weed and muddy gravel,

that mush,

but fire instead the forged enamel.

Make sirens ground from azurite

each with a hundred peacock eyes.

Frighten

yourself with griffon’s cries

and draw the haloed Virgin’s crown,

her blue enfolding robe;

the Son

Salvator Mundi, with his globe.

All things will pass. Only tough art,

the perfect bust, speaks to eternity,

outlasts

its time, outlives its city.

Rome’s emperors whose bones

are gone, whose robes are dust,

strive on:

their brows on buried coins don’t rust.

All the old gods are done, yet scribes

in their immortal lines kept them

alive

where art is sovereign.

So chip away. Never give up.

Cough, grapple, hammer your block

and trust

in the recalcitrance of rock.

GARRET

Low on the tiles a tomcat,

stalking the birds at the bath

on my balcony. Beyond, a garret

that for the sake of art

is framed exactly by two soil-pipes.

If I wanted to please I suppose

I’d place a vase right there

in the window, full of sweet-peas.

And picture for you Roxette

striking a pose with a brush

in her speckled mirror that reflects

a world of not-quite-enough.

Or Margy in just bra and pants

leaning out into the sun

with a bottle she decants

in slow dribbles on her pot-geranium.

Or the young poet maybe

who numbers anxiously his dry syllabics

to please his prof, earn his degree,

and scans for a theme the rooftops of Paris…

Sadly, the true view’s more prosaic:

no vines on the window-frame,

just rot, flaked paint and a mosaic

of soot that deckles the panes.

For your tart, your artist,

waitress, waiter, widower

there’s no charm in being piss-

poor, the opera’s tragic character.

One time there might have been

room here for love on a horse-hair

bed below the tiles—a dream

quick-breathing up the narrow stair.

But romance needs its mise-en-scene:

some central-heating and silk sheets,

four-poster luxury, thick carpet when

you step out to the tiled en-suite.

And now at night the prospect’s black.

Roxette’s out late, gone dirty-dancing;

and Margy won’t be stumbling back

before the sun comes glancing in.

A while since, the poet gave up on

his soaring for the perfect line,

became a hack. Bored then, he traded-in

Parnassus for an office and a mezzanine.

But still this view is all I’ve got:

my window-on-the-world, something

to watch: one lean old woman and the cat

she teases idly with a ball of string.

Théophile Gautier was also a journalist, travel writer and art critic. He tried his hand at novels plays and ballets too—most notably the scenario for Giselle. His friends included Victor Hugo and Gérard de Nerval. For a while, after the 1830 Revolution, he lived the bohemian life in the Paris suburbs but by 1862 he was established enough to be elected Chairman of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. Art, he declared, famously, n’est pas le moyen, mais le but.

* * *

José-Maria de Hérédia: Three poems translated by David Malcolm

TREBBIA

Dawn of an ominous day has bleached the higher ground.

The camp wakes up. Down there, the river thunders and groans

Where the horses drink of the light Numidians.

Everywhere the buccinators’ clear call sounds.

For despite Scipio, the lying augurs,

The Trebbia in flood, despite wind, despite rain,

Sempronius, Consul, dreams new glory once again,

Commands the fasces raised, marches out the lictors.

Reddening an obsidian sky with baleful blazes,

On the horizon burn Insubri villages.

Far off you hear the trumpet of an elephant,

And down there, under the bridge, back against the arch,

Hannibal was listening, passive and triumphant,

To the dull tramp of the legions as they march.

L’aube d’un jour sinistre a blanchi les hauteurs

EVENING OF BATTLE

O happy horse, to bear the weight of Antony – Shakespeare

The clash had been most fierce. The tribunes

And the centurions, rallying the cohorts,

Still drew in the air vibrating with their hard words,

The heat of carnage and its acrid perfumes.

With dismal eye, counting their dead companions,

The soldiers watched how, as wind with dead leaves plays,

Far off eddied the archers of Phraortes;

And from their brown faces the sweat ran down.

It’s then that there appeared, with arrows bristling,

The vermillion flux from his fresh wounds glistening,

Beneath purple flows and bronze gleams,

To the din of buccinas sounding a fanfare,

Superb, mastering his rampant horse affeared,

On a sky in flames, the Emperor in bloody streams.

THE CONQUERORS

As a flight of gyrfalcons round their charnel-house scream,

Weary of bearing their haughty miseries,

De Palos, de Moguer, captains and mercenaries,

Departed, drunk of a heroic, brutal dream.

They were going to gain the fabulous metal yield

That Cipango ripened in his distant mines,

And as the trade-winds blew their antennae inclined

To the mysterious shores of the western world.

Each evening, wishing for tomorrows from epics,

Azure phosphorescent of the sea of the Tropics

Their sleep in a gilded mirage would drown;

Or, in white caravels leaning forwards,

They saw rising high into a sky unknown

From the Ocean’s furthest deeps new stars.

Comme un vol de gerfauts hors du charnier natal

José-Maria de Hérédia (1842-1905) was of Spanish and French ancestry and spent most of his life in France. He was closely associated with Leconte de Lisle and the Parnassians, and almost his entire output consists of 118 sonnets collected in Les Trophées (1893). The poems attempt to capture central moments of human history with rigorous attention to the form chosen and a somewhat recherché language. He was a member of the Académie française.

* * *

PART TWO: AFTER 1900

Rainer Maria Rilke: a poem translated from French by Will Stone

NIGHTINGALE

To Mademoiselle Contat

Nightingale…, whose heart

Shines past the others,

Priest of love, whose cult

Is a cult of passion,

O’ sweet troubadour

Of the night that haunts you,

You embroider a ringing ladder

Upon its velvet abyss.

You are the voice of saps

That in trees stays silent;

But to us, your students, Nightingale,

You consign the same secret.

From ‘Suites Brèves’ – ‘Le Petit Cahier’ 1922

Rainer Maria Rilke (1875 – 1926) was an Austro-German poet born in Prague, a city he was at pains to relinquish. Only the city of Paris remained a stable presence for Rilke, his greatest lesson and most favoured creative terrain until the upheaval of the First World War. Rilke’s serial journeying was spiritually driven, his chosen mode of life one of necessary displacement with France, Italy and Switzerland providing the gilded sanctuaries which would enable this searching and meticulously sceptical poet the stretches of solitude he required to properly read his delicate existential seismograph and gain purchase on his inwardness. Though Rilke’s international reputation famously rests on the Duino Elegies and Sonnets to Orpheus (1923), his value to future generations is far more expansive, most notably in the vast and rich correspondence he assiduously curated.

* * *

Francis Jammes: ten poems translated by David Malcolm

From : De L’Angelus de l’aube à l’Angelus du soir

IT WILL SNOW NOW . . .

To Léopold Bauby

It will snow now in some days. I recall

last year. I recall my sadnesses

by the fire. If I’d been asked what it is,

I’d have said: leave me be. Nothing at all.

I thought a lot, last year, in my room,

while outside the heavy snow came down.

I thought for nothing. Now as then,

I smoke a wooden pipe with amber stem.

My old oak dresser smells as good as new.

But I was dull, for things like these

could not change and since it is a pose

to wish to chase the things we know.

Why then do we speak and think? It’s weird;

Our tears, our kisses, flow from speechless lips,

Yet still we understand them and the steps

of a friend are sweeter than sweet words.

We have baptized the stars without a thought

that they have no need of names; the digits

that prove in the dark the lovely comets

will pass, will not compel them, not a bit.

And even now, where are my old sadnesses

of last year? I scarcely can recall.

I’d say: leave me be. It’s nothing at all.

If you came to my room as asked what it is.

OVER THERE, THERE IS . . .

Over there, there is an old chateau, sad and grey

like my heart, where when the rain comes down

in the empty courtyard the poppies bow,

deflowered, rotting under the water’s weight.

Betimes, no doubt, the iron gate stood open

and in the house, old and bent, they hugged the heat

beside a screen edged with green ribbon

where the four seasons stood coloured bright.

The Percivals, the Demonvilles were announced,

who’d arrived, in their cars, from the town.

And in the old salon of a sudden gay

the old folk exchanged civilities.

Then the children ran off for hide-and-seek

or to look for eggs. Then in the chill rooms

came back to see the grand portraits’ eyes all dim

or where strange shells lay on the mantelpiece.

All this time the old parents murmured on

about a grandson, his portrait done in oil,

saying: “He died of a fever – typhoid –

at school. How he suited his uniform!”

His mother, who lived on, recalled again

her son died near the time of holidays

when the thick leaves hung and waved

in the great heats where fresh streams ran.

“Poor child!” – she said – “he loved his mother so,

he was never bothersome, no.”

And she wept still recalling again

that poor son, simple, good, dead at seven.

Now the mother’s dead too. Sad, isn’t it?

It’s sad like my heart as the rain comes down

and like this gate where the pink poppies bow,

glistening, rotting under the water’s weight.

THE CRANES

The cranes have passed down the grey sky, their cry grates

as the long lines file, cries of snow and shades;

the season’s come to decorate the graves.

The wretched, the blind, they’ll be beggars

with their hands red and shiny. They’ll stagger

to die on dark nights shivering in laughter.

The beasts will suffer. I saw someone begging,

an old man with cloths on his eyes, beating

his poor dog, tail to its belly, trembling.

He dragged it, choking it with a rope,

said: “Threw him three times in the water. The rope

broke. He comes back, the pig!” And the rope

dragged. The old dog, comrade in misery,

seemed to say to the old man: “Leave me be

still to cling to your clothes ragged and dusty.”

He, being man, worse than the dog, screeching:

“Pig! Pig! Next time I’ll drown you for certain . . . ,”

they went on both ’neath a great sky of tin.

THE YOUNG GIRL

To Stéphane Mallarmé

The young girl is white,

she has green veins

on her wrists, her sleeves sit

open.

You don’t know why

she laughs. In passing

when she cries

it’s piercing.

Does she have no faith

she’ll take your heart for hers

picking by the path

some flowers?

You’d guess here and now

she knows how it is.

Not always. Her voice goes

all low.

“Oh! My dear! Oolala. . .

. . . Imagine . . . Tuesday

I saw him . . . I laughed,” she says

like that.

When a young man suffers,

at first she’s silent,

has no more laughter,

just wonderment.

Down the little lanes

she fills her hands

with briar thorns,

with bracken.

She is big, she is white,

her arms are sweet.

She stands quite straight and arcs

her neck.

WHY DO THE OXEN . . . ?

Why do the oxen drag those heavy carts?

It’s piteous to see where their great heads swell,

eyes that seem to know the pain of all the fall.

They earn the peasants’ bread when times are hard.

Veterinaries, if they can walk no more

sear them with drugs and branding irons red.

And then in the fields full of poppies red,

the oxen harrow the earth as before.

One will break a leg, well, now and then.

They’ll kill him for the butcher meat

poor ox who heard the cricket greet,

obedient to the harsh commands of men,

the peasants who harrow in the sun’s mad stare,

poor ox who went he knew not where.

THESE ARE THE WORKS . . .

These are the works of man that are great:

that which pours the milk in wooden vats,

that which picks the ears of corn sharp and straight,

that which guards cows where the cool alder arches,

that which bleeds the forest’s birches,

that which twists osiers where bright streams pass,

that which mends the old worn shoes

by a humble hearth where an old cat scratches,

a blackbird sleeps, and with some happy kids;

that which weaves and clacks continually,

till midnight the crickets sing acerbically;

that which makes the bread, that which makes the wine,

that which sows the garlic and kale in the garden,

that which gathers the still warm eggs.

THERE WERE GLASS JUGS . . .

There were glass jugs of clear water

in the dark little garden of the Protestant minister

at his house with its severe air

and thick glasses, too, were there

on the cloth. Leaves lay against the windows’ shutters.

The month of June. On the narrow path

a piece of fishing rod, made from reed, broken small,

had been cast out, the day was both

grey and, as they say, right close,

like when great drops of rain are sure to fall.

By the dark window, sad, open

you heard a piano where the laurel glints.

The little windows were green.

There you should be happy, for certain,

like in books by Rousseau long time since.

THE LITTLE DOVES . . .

The little doves of the conjurer,

the little dove and his little sister,

suffer each day, it’s easy to tell,

in the little box in the hotel

and then again when evening comes,

And they’re there up the sleeve of the black costume,

and when they come out into the light

as is the show’s custom every night.

I SMOKED MY CLAY PIPE . . .

I smoked my clay pipe and saw the cattle,

yoke bar in front and slobbering muzzle,

resist the peasants, poking their backs

above the horns – and I saw, sweet flock,

the bushy ewes pass by on feeble legs.

The good dog feigned to be in rage,

and the shepherd cried: Wolf! Here! Wolf! Come!

And the happy dog gamboled up to him

and bit his crook quite facetiously

under the calm of a warm rainy sky.

WE SAY AT CHRISTMAS

To Mademoiselle M.R.

We say at Christmas, in the byres, at midnight

ass and ox in holy shadow chat.

I believe it. Why not? So, night scintillates:

star roses stay a station of the cross.

Through the year ass and ox know their secret.

We’ve no doubt. But me, I know each holds

a great mystery in their humble heads.

Their eyes and mine speak clearly each to each.

They are friends of the fields, great and gleaming,

where the slim sky-blue flax flowers grow trembling

beside the marguerites whose Sunday’s set

every day since they’re dressed in white.

They are friends to the crickets with great heads

who sing a sort of little mass,

so delicate, their gold buttons the bells

and the clover flowers the tapers blest.

Ass and ox say nothing at all of it,

being of a grand simplicity

and knowing well that all the verities

are not good to tell of. Far from that.

But I, when it’s Summer, the bees that sting

fly like small fragments of the sun,

I pity the little ass and wish they’d give

him small cloth breeches of some coarse weave.

And I want the ox who, too, knows the Good God

to have between his horns a fresh bouquet of fern

to save his poor and sorrowful head

from the fierce heat that makes the fever burn.

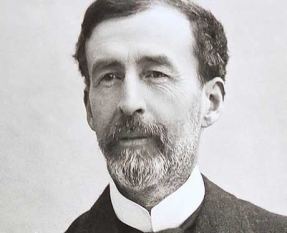

Francis Jammes (1868-1938) was a rural and religious poet, closely associated all his life with the regions near the Pyrenées. Because he was a rustic and religious poet using a relatively simple language and traditional forms, his success in the French literary world is seen as remarkable. Yet he counted Stéphane Mallarmé and André Gide among his admirers.

* * *

Oscar V. de L. Milosz: four poems translated by David Malcolm

SPRING CANTICLE

Spring has come back from his far voyages,

He brings us peace of heart.

Get up, dear head! Fair face, raise your eyes!

The mountain is an isle in the midst of haze; once more she is laughingly coloured.

Oh youth! Oh from the house the guelder roses hang!

Oh season of the wasp prodigious!

Summer’s crazy virgin

In the heat hums serenades.

All is trust, charm, repose.

The world is gorgeous, my beloved, the world is gorgeous!

A grave and pure cloud has come from an obscure realm.

On the gold of midday love’s silence has fallen.

Nettles bend their ripe heads in drowsy dream

Under the lovely crown of Judea’s queen.

Do you hear? Here’s the rain.

It’s come. . . . It’s poured down.

The water’s surface makes all love’s realm smell sweet.

The young bee’s here,

The sun’s daughter,

Flies to discover the mysteries of the orchard;

I hear the flocks bleat;

The echo answers the shepherd.

The world is great, my beloved, the world is great!

We’ll seek abandoned places where the pipes are heard.

Down there, at the tower’s foot, in the cloud’s shade

Sweet rosemary counsels sleep; and nothing has charm

Like the ewe’s infant, the colour of day.

From the veiled hill the tender moment sends us word.

Arise, proud love, lean on my arm.

I’ll part the willow’s leafy forms

We’ll look into the valley

The flower hangs, the tree quivers; they are drunk on scents.

Already, already, the corn is there,

Like sleepers’ dreams rising in silence.

My great sister, love power-girt,

Let’s run to where the bird calls us hidden in the gardens

Come, cruel heart,

Come, sweet face;

The breezes with child’s cheeks toss

Clouds of jasmine.

With fine feet she comes to drink at the fountain, the dove;

How white she is in the new water, see!

What does she say? where is she?

You’d say she sings in my new heart.

There she is far off. . . .

The world is great, best-beloved, the world is great!

The woman of the ruins calls me from a skylight:

See how her hair of crazy flowers, of wind

Has spread where the crumbling eaves end

And I hear the striped bumble bee,

Old bugler of days once innocent.

The time has come, crazy head, for us both,

To deck us with berries that breathe in the shade.

The oriole sings down the most secret path.

Oh my thought’s sister! What is this mystery?

Enlighten me, wake me, for these are things seen in dream.

Oh, I’m asleep, sure enough.

How life is grand! No more lies, no more grief

And flowers rise from the earth

Who are as if the dead forgive.

Oh month of love, oh voyageur, oh day of joy!

Be our host; stay;

Under our roof you’ll rest peacefully.

Your grave projects will doze off in the winged murmur of the avenue.

With bread, with honey, with milk we’ll feed you.

Don’t fear,

What do you have to do down there?

Aren’t you happy here?

We’ll hide you from all care.

There is a lovely secret room

In our house of rest;

There, through the open window green shadows come

Onto a garden of water, solitude, and gracefulness.

He listens . . . he pauses some . . .

How the world is blessed, my beloved, how the world is blessed!

THE BERLINE STOPPED IN THE NIGHT

Awaiting the keys

xxxxxx– He’s looking for them doubtless

In the garments

Of Thècle dead thirty years since –

Listen, Madame, listen to the old, the deaf murmur

Of night in the avenue. . .

So little and so weak in my coat wrapped so,

I’ll carry you through the thorns and the nettles of the ruins right to the high, black door

Of the chateau.

It is thus the grandsire, once, returned

From Vercelli with herself no more.

What a house, so mute, mistrusting, black

For my child!

You know it already, Madame, a tale so dark.

They sleep scattered in far countries.

A hundred years since

Their place waited once

Deep in the hilly lands.

With me their race ends

O Lady of these ruins!

We will see the lovely room of infancy: there,

The supernatural depth of the silence

Is the voice of the portraits obscure.

Curled up on my couch, in the night,

I heard, as in the hollow of some armour,

In the sound behind the wall of the thaw’s stir,

Their hearts’ jar.

For my fearful child a homeland so savage!

The lantern goes out, the moon slips through the haze,

The screech owl calls to her daughters in the boscage.

Awaiting the keys

Sleep a little, Madame – Sleep, my poor child, sleep

All pale, head on my shoulder.

You’ll see how the uneasy forest

Is beautiful in the insomnias of June, embroidered

In flowers, o my child, like the daughter preferred

Of the mad queen.

Wrap yourself in my travelling coat:

On your face the great snows of autumn melt

And you are drowsy.

(In the lantern’s beam she turns, turns with the wind

As in my childhood dreams she turned

The old woman – you know – the old woman.)

No, Madame, not a sound.

He is quite aged,

His mind deranged.

I wager he’s gone for a drink.

For my fearful child a house black like ink!

Deep, deep, Lithuanian lands lie around.

No, Madame, not a sound.

House black, black.

Locks rusted.

Vines dead.

Doors bolted.

Shutters closed.

Leaves on leaves for a hundred years where the avenues go.

All the servants are dead.

I – I’ve lost my memory.

For the trustful child a house so black!

I remember only the orangery,

The great-great-grandmother’s, and the theatre.

The owl’s young ate there from my hand.

The moon peered through the jasmine.

That was once.

I hear a footfall where the avenue lies.

Shadow. Here’s Witold with the keys.

MISTS

I am a great November garden, a garden of tears

Where the outcasts shiver from of the old quartier;

Where the fogs’ wretched colour says: Always!

Where the fountains’ patter is forever Nevers. . . .

xxxxx– Around a ridiculous meditating bust,

(Marie, you’re asleep, your mill’s turning too fast),

Where the round turns of the old quartier’s despairs.

Do you hear the round that weeps in the garden drowned

In blind mist, deep in the old quartier?

Poor dead friendships’, burlesque forgotten loves’ sound,

Oh, you, lies of an evening, oh, you, illusions of a day.

Around a ridiculous meditating bust,

(Marie, you’re asleep, your mill’s turning too fast),

Come dance the black round of the old quartier.

The mist has eaten all, nothing’s gay, nothing grieves,

A dream is as hollow as the real.

But in the park where you knew summer’s feel

The round, the immense round turns, turns always,

Friends you replace, lovers you leave

(Marie, your mill’s turning too fast, you’re asleep. . . .)

I am a great November garden, deep in the old quartier.

THE CHANT OF THE CHEVALIER ZYNDRAM

Like joy’s or alarm’s fires

On night’s mountains, the wakening scream

Of the eagle of the solitudes

Or middays on the haffs, colour of tears

The cold light of dreams.

So let it be you, young soul in dazzling ascents,

Imperial virgin elated

Of chants, wines, cruel laughing suns’ heat;

Barbarian goddess, sweet and terrible, the incense

Of future crowds, darkened with tears and sweat.

My heart, under the rotten leaves of dead years past,

In the mud of roads forgotten,

Sleep the bleached bones of loves and friends

The worst and the best.

We are like stones to the lake bottom thrown,

Like leprous pariahs among men,

Like bread with pity poisoned.

Shame has spat on our blazon.

Like the old bald crows for which the horizon

Is shelter for winter, and the flesh of bodies a nest,

So the days of life are lonely throes of dying nights.

xxxxx– Like the yellowing leaves’ flight

In the red winds of autumn sunsets sounds the same

As your name.

But blood enough is left to stain the banner,

But a string still quivers on the rusted lute

Which will know how to weep and cry out

The great poem of injustice and hunger,

And this old epée gnawed by the moon

Still recalls the poor man,

The widow and the orphan.

A glance for our good old chateau of misery,

An orison for the worm-eaten cross

Where the road forks,

Nothingness in the heart, eyes burnt by the black north wind,

The rusty beard the smell retains

Of a bitter wine,

Let us go down towards life; she will tell us where duties begin.

As long as there’s still hope for adoration or belief,

A barrel or two of wine to quaff,

The lean knight Zyndram is not lost.

For the worst fate is more lovely than the waves!

If you weep or laugh by the empty graveside

Of your heart; if you fear your hands – a parricide’s –

And if the bleeding fingers of the cold Eumenides

With disgust have cut the harp of your nerves,

Arise, the air is young, the water rings as the winds fly

And the joys of long ago sigh in the echo.

Gird yourself with love for those whom you despise:

The moon is yours, how could she not be lovely so?

Revive, and on the Rhine of grey tears

May the dazzling swan and the white device

Tell the of the hero’s return at the last!

Like the moment of the pillar of sand in the desert,

Like the cry of the lightning that falls seaward,

May each of your moments be, my soul

Of bard and knight,

Henceforth.

xxxxx– The trumpets call, the tail of flames

Of the mountains affrights down there the barbarous night. . . .

Yes, yes! There still remains something for us to love!

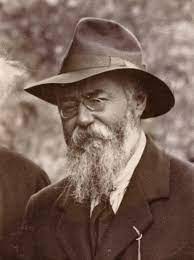

Oscar Vladislas de Lubicz Milosz (1877-1939) was born in what is now Belarus of Lithuanian, Polish, and Jewish ancestry. From his teens he lived and studied in France. An accomplished polyglot, he identified himself with the newly independent Lithuania after the Great War. He wrote verse, fiction, and drama in French. His writing is seen as esoteric, metaphysical, and rhapsodic. The Nobel prize-winner Czesław Miłosz is a relation.

* * *

Robert Desnos: Daniel’s Geometry: four poems translated by Timothy Adès

For the son of the composer Darius Milhaud, 1939

THROUGH ANY POINT ON A PLANE

Through any point on a plane

You can pass only one line perpendicular to the plane.

So they say…

But through all the points on my plane

You can pass all the people and animals on earth

So your perpendicular makes me laugh.

And not just people and animals

But plenty besides

Pebbles

Flowers

Clouds

My father and mother

A sailing-boat

A stovepipe

And if I choose

Four hundred million perpendiculars.

MOEBIUS RING

This round-returning road I run

xxxxWon’t be the same when I’m half-done.

No use my going straight ahead,

xxxxIt takes me somewhere else instead.

I go right round but the heavens change.

I was a youngster yesterday

xxxxI’m a man today

xxxxThe world is strange.

A rose that grows in rosy rows

Is not like any other rose.

THE ANGLE SUBTENDED…

The angle subtended…

One moment, what angle?

I don’t want to know

If it isn’t the angle

The one where I’m grounded

To count to one hundred

Before shouting GO!

You strangle me, angle,

Engulfed and surrounded.

La Belle Angleterre

Not Angles but angels

Fair England of legend.

My eyes are shut tight,

My night has descended.

The angle subtended…

THE PARABOLA

Parabola hey! my nanna

Parabola bored in its cage

Rather be on the branch

xxxxBranch too low

xxxxSun too high

I watch birds fly

To earth, to sky

xxxxBranch too low

xxxxSun too high

Funny birds

Nest far from earth

xxxxBranch too low

xxxxSun too high

Robert Desnos (1900-45) was hailed as ‘the prophet of Surrealism’ – ‘Words have stopped playing: words are making love’: so said André Breton. He took Surrealism out into the world, on radio, in films, in journalism. He was close to Duchamp, Prévert, Alejo Charpentier. His hundred poems for children were late works, as were his great sequences against the Occupation. He was an active Resistant, a martyr who died in the Nazi camp of Terezin.

* * *

Marie-Claire Bancquart : twelve poems translated by Anna Gier

From Qui vient de loin (Pantin: Le Castor Astral, 2016)

… Foot upon a step

sixty years gone by.

A snagging

Of sensations that were pretending to be dead.

The staircase suddenly overruns

with uncles, neighbors, missing cats

a whole lifetime ascending

towards memories familiar enough to be present

but this is no longer the same staircase

the other was destroyed with the house.

Now they’re putting up a big shopping center over there,

and one must be very old to remember these bygone places,

nowadays more distant than the moon.

*

There are wounded words

at the door

don’t open it

they’re stacked up, they’d collapse in a heap

some keep climbing the stairs

they’re seeking

perhaps

silence. Their silence.

If you opened the door

they would enter the dictionaries

they would occupy those quiet

alphabetized domiciles, where nothing shows

that true horror does exist

but blood

would flow from them

each time we reached the word Blood.

*

Pollution over the city.

Weave of evenings

in confused greys.

We would like to grant a charter to the wild roses

so they may climb up

all the balconies

cultivating worship

of impalpable purity.

*

Is it possible for us to

delight or distress stone?

With the attention we give so partially

to the living

who are we before the apparently inert?

— Our palm against an old wall,

we believed we only touched the unfeeling.

The mineral warms under our flesh

begins an existence, barely perceptible:

tiny mosses, furtive creatures.

A very faint call to share in

a secret life

reaches us from the depths of time:

the stone exudes a bit of moisture, like a tear.

… Subtlety of obscurity, sometimes.

*

With each spring a new bud opens

into sweetened blonde leaves on the branch

would that I could metamorphose

from woman into horse

so I could reach

with my lofty lips

one of those flames of honey!

*

We have no interest

in paying full price for your catalogue of anxieties

shouldering the fall of the gods

lowering our voices over headlines, conspiracies.

We refuse the mass embarkation

towards shipwreck.

We withdraw to our domain

though narrow

like the flanks of the whale were for Jonah

still liveable:

a thistle’s capitulum

closed

over a bee.

*

The ark and the axis:

these harmonies devoted to the cosmos

must be recovered within us

quite simply

because all that exists cries out and thinks.

Ark, our resonant dwelling in common.

Polyphony of beasts

caged two by two,

rustling,

even the butterfly and the blessed ladybug.

Thus reverberates our heart

and our vertebrae

their architecture so fragile

are the axis of our fleeting higher thinking

which we recover drafted

in the fish of the deep.

*

I retire to you as if to an island

inhabited by music and words

but alone

amidst a speechless sea

an island

that can move that can love

that in itself is enough.

*

Write

for the stranger who’ll read this

in a room

that I’ve never seen?

To meet each other

would be indiscretion;

the two of us are nearing our outset in things

in them

we will find an inexhaustible exchange

and the words will dry out in an attic somewhere

on the earth

which we will have

forgotten.

*

We will work on the possibilities

of our existence.

… Our application to our own life

is very white in color

on it

music

awaits notation

a poem is hesitating.

It may be worth furthering

like antimony

on its way

to the alchemists’ gold.

*

And what, mage of expectancy

casting under dizzy spells

abruptly

interrupted

then taken up by

the charm of the seasons, the conflagration of faces,

the very name of life

tolls for thee like a flash of hot energy…

*

The place of the poet?

— An undeserted island

a solitude widely shared

peopled with intermediaries,

metamorphoses,

houses

with

walls full of

portraits of strangers we would’ve wildly loved.

Marie-Claire Bancquart (1932–2019) was a prolific poet, novelist, and academic whose literary and critical contributions to the Francophonie have been widely recognized, including by the Académie Française with the 2001 Grand prix de la critique littéraire. Confined to a full-body cast for prolonged periods of time as a child due to bone tuberculosis, Bancquart’s experience of subjecthood was shaped by an acute awareness of physicality and an appreciation for material existence as a ‘community’ of all matter intermingled in changeable configurations. Qui vient de loin, the 2016 collection from which the translated excerpts are taken, gives full expression to her philosophically atomistic worldview and the appetite for life it accommodates, celebrating fragility and finitude as the terms of humanity’s participation in the cosmos.

* * *

George Goddard: three poems translated from his own St Lucian Kweyol

MORNING COFFEE

Morning coffee

takes me back to the archives of my childhood

my grandmother,

her dibélwé constant as her morning prayers

brewing café noir

from home-grown coffee beans;

waking me at 5

When the feisty scramble for mango la rose,

mango dou-i-dou

had ended with their season

and there was no reason to jump out of bed

but a little sip of ground coffee

This morning

there’s Nescafé in my teacup.

HILLS…

Hills are rising, then climbing down

under the beauty

of the sun’s crown;

hills are rising, then climbing down,

sun dries up the land as

your leaving shrivels my soul

Hills are rising and climbing down slowly

trying to comprehend

an intimacy at an end

suddenly

Mountains tumble down

leap high to touch clouds;

the rain-season’s clouds

cry a flood

for a love that is gone,

dispersed

In the air like a mist;

and still within me I insist

you will return,

return in the end…

yet hills fly high

dive down with the wind from the sea;

wind blows dry leaves

to fall from the trees

scattering these

in many shards of my heart, abroad.

EN BAS LA TERRE

I will never understand

why you search

So many times you had found it

(so I thought)

yet you search

And you don’t say “love” or “truth” –

you do not;

you would admit you search

“En bas la terre pas ni plaisir”

grand aïeuil-nous dire, alors jeune homme

faire plaisir-‘ous ici:

life’s a frenzied season, transient,

that ends in an amnesiac lent

so laugh and fête

Run and laugh and fête

cry now and then

but do not search!

Yet it may well be

that in the unfettered season you have

xxxxxxxwilled your life to be

unwittingly you search

George Goddard is a Saint Lucian writer and poet who published his first collection, Interstice, in 2016. He writes both in English and Saint Lucian French Kwéyòl. He is currently putting together two other collections. His work has been published in Caribbean and international magazines (on-line and print). Among these are BIM: Arts for the 21st Century (2021, 2020 & 2017), Interviewing The Caribbean (2020, 2017), Re-Markings (2021), The Caribbean Writer (2021 & 2017), Punch (2018) and The Missing Slate (2015).

* * *

Gilles Ortlieb: Four poems and a prose translated by Stephen Romer

BROUILLARD JOURNALIER (Obsidiane, Paris, 1984)

A zinc roof laid bare

through the broken, dented snow :

first inklings, bitterness recouped,

the streets still untempting

and the quayside, stiffened trees.

Not so long ago

a penny whistle could topple cathedrals

—winter glimpsed, through the thousand

declensions of thought. And the weary kiss

that ivy lays upon the waters,

light thrown up on the bridges

and on all of us, from the poorer quarters,

veterans of seasons past.

ABSURDE DE S’OBSTINER

Absurd to trudge on like this

against the oozing wind of fixed

winters. Experience teaches you to scarper quick

when your steps freeze under rags of storm.

There’s a pocket knife, for the day’s rations,

papers scattered round the sleeper and the certitude

—recognized on waking—

nothing will absolve him from his headlong flight.

À NOUVEAU, LA CHASSE

Once again, it’s the sardonic but stubborn

quest, floated along the streets. Pencil, tobacco

and book, the requisite paraphernalia,

until writing wearies, and being alone

with one’s own verses.

Then hunger calls, to appease itself,

and I’m drawn to the lights for a bit of warmth.

I watch the pedestrians file by

their washed-out gaiety, eternally played out

and a voice at my shoulder

‘alas, you doubt everything, and yourself…’

QUE LA RUE

So let the street be my addiction,

the acrid vapours over the termini

the intermittent spitting of the storm :

the summer’s allotment, and slow afternoons

where I walk, trapped in a cipher of footsteps,

to watch the barges disappear under the arches

and smoke my endless, thin cigarettes

to bring these syllables to the surface.

An isolated quotation, penned in a margin :

‘The writer’s best work, and it is the same with any craftsman, comes once the first weariness has been overcome’. My poem on Hagondange would be an example of this : I have never written it, even though every time I pass the place on the train its ghost or the desire to write of it revives, but this is as quickly discouraged by my incapacity to describe the dullness of the place. Which in turn is to ask, once more, the age-old question : is the lack primarily mine, which is then imposed, forcibly, on a landscape that is not to blame but still… or does it indeed emanate from the sight of those over-straight main streets and the adjoining suburbs with their shuttered windows, which transmits lassitude to the eye regarding it, without its knowledge ? (One day, though, I shall get off at Hagondange and I shall walk up the main street long enough to approach the idea of what I had come for, before turning back, and taking refuge in then only restaurant open near the station, Au Pavillon d’Alsace, where for forty-nine francs drink included I can regale myself with a sclerotic-looking choucroute. And the bread will taste a tad acidic in the basket as they unroll the green baize in the public bar, and a retired unionist will sing out ‘Bonjour, belle enfant !’ in reply to the ‘Salut, Lucien !’ proffered by the amenable over-blonde waitress, and a ray of light, as if refracted through stain glass, will strike my beer mug, and then I shall be able to say that, for an instant, the lack is indeed in the eye that observes and not in the object observed.)

Extract from ‘Notes de février sur la neige et l’immobilité’, La nuit de Moyeuvre (2000).

Gilles Ortlieb (b 1953) has become, over the years, a familiar name to readers of modern French poetry in translation. He has been published in anthologies and reviews, in translations by Jennie Feldman, Patrick McGuinness and Stephen Romer. Ortlieb tends to be classed among the poètes du quotidien, or the poets of daily life, a term that is really redundant in any tradition other than the French, where the notion descends from ancient quarrels. But Gilles Ortlieb, essentially by amassing details of outer phenomena, subtly matched by an inner necessity or pressure that is more felt than stated, has made le quotidien all his own. The themes in the intense, laconic early poems given here remain essentially the same, though they are amplified in the later work. Ortlieb has also written biographies of Baudelaire (his last spectral years in Paris – Au Grand Miroir (2005)) and of a little-known Portuguese poet and visionary who ended his days in a mental hospital, Angelô de Lima (Angelô, 2018). In these, Ortlieb invites the reader into the biographical process itself, subtly weaving into the writing his own responses to things and places encountered along the way.

* * *

Maram Al-Masri: ten poems translated by Hélène Cardona

From The Abduction (Le Rapt, Éditions Bruno Doucey 2015)

WE SOW

We sow

she sprouts

she grows

she hurts

she explodes

she gives birth

to an infant in a poem

Between her thighs

it flows

like a waterfall

a small body

naked

warm

he cries,

I am here

COME ON, SUN

Come on, sun

wake up!

Let your yellow hair float

over the cold shoulders of the earth,

over the houses and the streets.

Heat up stones and asphalt –

dance, sun, ablaze!

Make this this day a beautiful day,

because far from this cold wall

in a field of colors

where the sky is made of tales

and where the trees are poems

I will take my little one for a walk.

DANCE, DANCE

Dance, dance

my son

because you were born

to teach the birds

to fly

dance, dance

my son

so that the restless heart of the world

may calm itself

to the rhythm of your steps

dance, dance my son

so you may learn to fly

PROMISE ME

Promise me

if I close my eyes

you will run into my arms

to light up

this dark world

Promise me

if I open my eyes

you will stay

FORGIVE ME, MY LITTLE ONE

Forgive me, my little one

if I didn’t come quickly

on foot, the path is long

and I couldn’t afford the tickets

forgive me, my little one

this excuse

must seem feeble to you

surely

I could come on foot

or borrow the money

or save some money

stop smoking

(though I don’t smoke)

or even sell my mother’s jewels

to buy the tickets

forgive them, my little one

when I arrived

they prevented me from seeing you

EVERY MORNING

Every morning

I wake

hoping to prepare your meal

every morning

I open my eyes

how I wish you could wet

my face with kisses

every morning I wake

how I wish you’d woken me

much earlier

having fragmented my sleep

to smithereens

I’M NOT SO OLD

I’m not so old

so why

do I feel this way?

Why has the hair of my dreams turned white?

why has the shine of my eyes

turned to ash?

I’m not so old

so why

can I no longer taste the honey of life?

And why has the morning song

I used to hum

become silent?

I DON’T WANT TO GROW OLD

I don’t want to grow old

so my child recognizes me

the day he comes back

to see me

I don’t want to die

like my mother

because I have a child

though not in my arms

but one day

for certain

he will need me

FROM MY WINDOW

From my window

I see houses

their windows often closed

I imagine what moves

behind those thick walls

I see a man returning home

and a woman going out

wearing a black coat

They have two children

life has allowed them to watch grow

A house like mine

may be hiding wounds

may be hiding stories

One Sunday

the day of the feast of love

I see the man coming back

to his house

with a bouquet of flowers

A house that is not mine

dresses in joy

TO CONFRONT SO MUCH PAIN

To confront so much pain

and shatter the statue of sorrow

I sprinkle my smile

like flower pollen

on the treetops

electricity pylons

sidewalks

the faces of passers-by

bread