*****

Previous Essays

THW5: March 7, 2017 THW4: December 6, 2016 THW3: September 1, 2016

THW2: June 1, 2016 THW1: March 1, 2016

*****

When he first walked into my library, on a council estate in Grimsby, to return some books, Sam Gardiner did not cut the obvious figure of a literary giant – but we soon slipped into the sort of conversation that those who spend long periods standing behind public counters long for: fluid, informative, funny and unexpected. He knew the library because he lived nearby, but during his regular visits to the main library in town he’d discovered that a number of the ‘interesting’ poetry books were on the shelves of my own tiny branch, so rather than order them, he’d dropped in. We discussed poetry, our personal tastes, the work of local writers, arranged to exchange a few of our own books that the library service couldn’t provide, and very briefly, in passing, Sam mentioned that he himself wrote and had published a few things. I was surprised to see Sam return the following day, but pleased as I’d brought in a few things in to lend him. After graciously taking them and saying that he would read them closely, he dug into the deceptively copious pocket of his sports jacket, and pulled out a copy of his book, Protestant Windows, offering it as evidence that he ‘really did write poetry’, and that it wasn’t just ‘self published stuff about cats and grandchildren’ and pointed out that ‘that one won a national poetry competition.’ I took the book and it was, of course, a delight.

Like that first conversation, the book was unexpected, not only in its origins but the richness of its subject matter, its influences, its formal choices and variety. This first collection, like the two books that followed it, was at the same time immensely readable, and deceptively simple in its clarity and openness, which lulled the reader into accepting the juxtaposition of ideas and language in radical and potentially disarming ways. The grand-narratives of science are given as iterations of the mundane writ large in which

…continual cell replacement

ensures that every seven years,

or hereabouts, a complete replacement

puts out the cat and brings in the milk

[Approximately Us, TMA 2010]

Like that last glass of brandy

you were 71 per cent water

Your dying was less a question

of earth to earth than water to water

[Water Content, PW, 2000]

Every million millionth star

is circled by a planet where an Adam

aged 14 or so switches off the bedside lamp

[Concatenation, TMA, 2010]

And perhaps inevitably it was Sam who would title a poem ‘Scientists Have Discovered’.

Sam was equally at home in the social sciences, where deft phrasing of mundane observations also stood for larger social concerns; the habitus which reveals social capital and betrays the rot or the consolation therein. So ‘mitreing the dado’ becomes a kitsch symbol of shifting social mores, in a poem about the inevitable personal dissatisfaction of contemporary identity politics, the wry and the knowing making palatable the discussion of the unbearable. While the ‘drudgery’s worth’ of a couple of working class tideline coal collectors, renders touching what could have been a mawkish piece of social-realism:

I knelt on the landing, mitreing the dado

having rewired, having moved, the two-way switch,

and the mannerisms of my socio-economic group

[Identity Crisis, TNS, 2008]

I hope they get their drudgery’s worth:

a firelit hearth, perhaps: warm hands

at bedtime to touch each other with

[Sea Coal, PW, 2000]

Again this humour and apparent simplicity allowed the repeated relocation of subjects (and the reader) into anomalous or anachronistic contexts, comparisons which were at turns absurd, damning, obtuse or anarchic;

and when she gashed her breasts

with a steak knife and screamed,

‘Make bloody poetry out of that,’

he did, the bastard.

[Poetry, PW 2000]

Darkness will not have fallen there,

it will have risen from the woods

Outside your window, having skulked

all day in root craters, in dens and burrows

as patches, bolts and bales of night

[Future Imperfect, TMA 2010]

underpinned with a formal structure and internal logic which allowed his absurdity and anarchy a seemingly clockwork mechanism. The very humane observations of human behavior in Sam’s poems belied another apparent contradiction: finding the personal moment in the grand narrative, both marrying people and Politics, while troubling social truths, much in the style of Douglas Dunn.

The overriding feature of that first book he lent me, and Sam’s work generally however, was its wit. Not just its humour, though it had that in spades, but its creative intelligence, the satisfying way that an argument, a comparison or a sentence would twist, turn and resolve itself, playfully toying with the reader. At the same time this was a puckish humour which was not at all safe, and could be flattering and caustic at turns. And this turned out to be not only a satisfactory review of his book in Sam’s eyes (following my assessment of his work we set immediately about forming the Nunsthorpe Poetry Group), but also a good measure of (my relationship with) Sam himself. Always probing with every remark, always with a smile at the edge of his mouth as he toyed and tested with each question, at once teasing and encouraging.

The poetry prize Sam had mentioned to me turned out to be not a, but the National Poetry Competition, and his appearance in the 1993 shortlist had been as unlikely and surprising as his sudden appearance in my library. Poets with nascent reputations had won in the past and frequently contended with the more established names, but as an almost entirely unknown name Sam knew when he attended the award ceremony that he’d done surprisingly well to get in the room. He would describe how he and his wife, Eileen had gone down to London as an unaccustomed jolly, happy in the knowledge that Sam would be first called, to collect last place, and the rest of the evening could be spent relaxing and soaking up whatever glamour and excitement that better known literary faces could provide. But as the evening elapsed, and Sam’s name was yet to be called, came the dawning realisation that Sam had done better than ‘surprisingly well’, would be not just shortlisted but runner up, then second prize, then inexplicably the winner. He would recall the ‘bear like’ hug that Sean O’Brien had given him, reassuring him as he went, terrified and a little bewildered, to receive the award. He would tell this story, insisting that ‘they must have thought it was by somebody else’ simultaneously self-effacing, and immensely proud of his achievement – as though it were his job to knock himself off any self-prepared pedestal. If Sam’s invitation had included some coded acknowledgement that his poem, ‘Protestant Windows’, had won, then he was not well inured enough in the world of award etiquette to realize. Had he realized that attendance would mean him being centre of attention, he may not have chose to take the trip as, whilst not a shy man, he disliked public speaking and never gave readings.

The absence of his voice on the poetry reading and performance circuit explains partially both how such a distinctive and consistent talent could have been still unknown at the time of the award back in 1994; but also why, even after the recognition of the National Poetry Competition, and the increased output and prodigious rate of publication after his retirement from his job as architect shortly afterwards, Sam Gardiner never became a well known name in this country. His reputation and recognition amongst those he published alongside was strong, and he maintained vigorous friendships and correspondences with a great number of poets and editors, both well known and unknown, but amongst a wider reading (and buying public) his exposure was limited. His reputation abroad (particularly in the US and in Ireland) was as strong as any other non-resident poet, a fact commemorated in the translation of a collection of his work into Dutch – a copy of which took up residence in his jacket pocket, acting as an impromptu folder for whatever manuscript he was carrying with him at the time. Again immensely proud of the achievement, if asked what the book was he’d self ironically feign modesty ‘what? this old thing?’ and claim that it wasn’t a translation at all, but that ‘the Dutch have decided that I’ve spelled everything wrong, and have sent me corrections – apparently I don’t have enough vowels’. I suspect Sam was as well known a poet as it is possible to be without giving personal appearances, judged as he was, solely on the content of his work as published, rather than that combination of demeanor, showmanship and personality that sells a performance; but to those of us that knew him, his friendship was a (sometimes biting) entertainment in itself; those who merely read him, liked his work well enough to push his books through several editions, an achievement of too few poetry titles these days, with his first collection being reissued in 2010 in a slick, reset, 10 anniversary edition which threw off the drab generic covers of the first pressings.

It is easy to see why ‘Protestant Windows’ won the national prize, and why five years later Lagan Press were so keen to use it as their title poem. In 1993 a poem about a protestant who clings to his window sash as he would his lodge sash, eschewing the personal and environmental security offered by those selling new windows (and ideas) must have seemed timely, in the bloody run up to the Downing Street Declaration. However as much as Gardiner’s satire could have been a heavy handed cartoon, it was not at all one-dimensional, trading as much on arguments between architectural aesthetics and environmental pragmatics and the relative dogmatisms of those disciplines, as it does the supposed religious alignments of its protagonists. The insignificant squabbles of two double-glazing salesmen and their customer who stands by the sash of his window as he does the sash of his lodge; both are given ridiculously grandiose justifications through sectarian and secular invocations (King Billy and his sashes/’Our Earth’ and rising CO2) – presumably both adopted through convenience rather than (in 1993 still contestable) evidence. While the ‘martyring’ of our Ulsterman by the very sash he had made his petard, the pantomime character of the events is recast and Gardiner pulls out and reframes the situation in the longer hope and fears of Protestantism from the Oxford Martyrs onwards – their light which hoped to inform the world, invisible and impotent in the rise and fall of ages, planets, galaxies. Yet for all its contextualizing, it remains a funny poem on a human scale, of one man’s probably inescapable tragedy. That first collection features many poems, written from many points of view, which offer satires and sometimes meditations of despair of Irish politics and sectarianism. As Fred Johnston noted “If Gardiner’s poems are political they are subtly so, operating outside the range of the predictable refrains and noises and who opt for the black-white, victim-oppressor view.”[1]

However, to say that Sam’s work was entirely unknown at the time he won is not entirely true, for he’d had a previous career, and previous acclaim, in earlier times under a different name. Prior to the publicity of the NPC, Sam had been publishing as Trevor Gardiner, the name by which he had always been known to friends and family, but before that, through the 1970s while he was living in London, prior to adopting Lincolnshire as his home, he’d used his initials S.T. Gardiner and had an entirely separate career. Moving to London as an practicing architect in the late 1960s from his native Portadown, via Lurgan and Belfast, Sam had ensconced himself in the London poetry scene – joining Norman Hidden’s Workshop group, and publishing in a number of the small magazines of the time, including Hidden’s New Poetry, and opening in 1973 the Poetry Bureau, an office above Leicester Square tube station, from which he offered ‘professional poetry criticism and marketing advice’. This was no vanity service as one of his clients, Tony Thorne, remembered

“I was fortunate to meet up with Trevor Gardiner of the Poetry Bureau and later The Poet’s Yearbook, who analysed, shredded and then minced my efforts with lasting effect. The devastating criticism developed and guided my efforts and determination to produce something that others might appreciate.”[2]

Despite this excoriating sounding experience, Tony remembers Sam as ‘a kind and generous person’ who guided him as editor, through several publications, both non-fiction and poetry.

Perhaps it was the red faïence tiles on the front of the Bureau’s building, reminding him that this was the original office of Wisden’s, which made Sam decide that what poetry needed was an almanac. Sam was given a printing press by Tony Thorne and through 1974-5 he set about producing the first Poet’s Yearbook, printing them himself from his own typescript. Each edition from 1976-79 listed and taxonomised all of the country’s poetry publications, publishers, magazines large and small, and published poets of the preceding year, but also collated and analysed statistics on who published what material and in what quantities, as well as detailing prizes, awards, poetry groups and societies. They were an immediate success, and are still cited as the authoritative documents of the period, but their impact is perhaps best summarised by Peter Forbes (later editor of Poetry Review, and so, occasional publisher of Sam’s work), describing his own entry into literary circles:

“When I started to write poetry, I did not know anything about little magazines. I knew they existed, but I did not know one from another. Stand was the first magazine I came across. So I wrote with my poems and had a nice letter back saying “they are not for us” and they recommended an organisation called The Poetry Bureau. This was S. T. Gardiner, who edited The Poetry Yearbook (sic), which was a very useful publication and, of course listed all the magazines. They actually had a critical service as well. Anyway, they put me on to some little magazines, including one called Samphire and they were the first magazine to accept me.[3]”

This process, which Sam had described as ‘marketing’, and the sometimes painfully honest but constructive criticism, is precisely the sort of feedback I remember from Sam in workshops and poetry surgeries, always supportive but with a practical eye to publication born of years of experience.

The success of Poet’s Yearbook reached its apogee in 1977, producing new editions for ‘77 and ‘78, instituting a regular prize (judged by Edwin Morgan) and publishing the best collections, instituting a new journal (for which, perhaps only an architect would think Poetry Survey an attractive title) and publishing a ‘biographical anthology’ in which new poets published not only their work, but biographical and contact details, in order to foster a national poetry community. Names such as U.A. Fanthorpe, Peter Robinson, John Lucas, Peter Forbes and Connie Bensley all joining the collective in that year’s Autumn Anthology. Sam’s poetry was simultaneously becoming recognized, with Howard Sergeant selecting his ‘First Time Abroad’ for inclusion in New Poems 1976-77 (the annual P.E.N. anthology of the year’s best work), a terrific poem despite its age, it bears the hallmarks of Sam’s later techniques – the final stanza is disrupted by a trick false-ending and the turn of a line, and just as the poem seems about to end as a slight joke, it is undone with a line of unexpectedly phrased beauty and simplicity

xxxxxxxxxWinds moan.

Clouds drift.

xxxxxxxxxThe earth turns

Over and goes to sleep, and so do you,

Breathing gently.

I go to the window and uncurtain the dusk.

[First Time Abroad, 1977]

leading Robert Greacen to assert that ‘among the lesser known poets the one who stands out is S. T. Gardiner.’[4]

However, being a victim of the Yearbook’s success, personal circumstances of work, and raising two young children, all meant that unexpectedly at the end of the year Sam returned the printing press (‘the amount of time he spent using it apparently began to conflict with his family life’), changed architectural practice, and moved to Cleethorpes. While he issued extracts of the Yearbook data through the Poetry Society and a final P.Y. award collection in 1978, and a final yearbook in 1979, journals through the early eighties reported that queries as to a new edition were going unanswered at the Yearbook’s last known address, and the enterprise was initially mourned, and later imitated by others.

Whether Sam maintained any of his literary contacts through the 1980s I do not know, but as his career regained its vigor he certainly had no trouble rekindling a network of notable correspondents. At the poetry group through which we came to know each other, I held the responsibility of photocopying each member’s poems for the rest of the group, which gave me a unique insight into people’s work as I placed each poem face down on the glass, and saw on the reverse the school worksheets or final demands that had been pressed into service as manuscript by the various members of the group. Frequently Sam’s would be the opening of an erudite and chatty letter to some noted poet, critic, or editor, perhaps a précis to submitting a poem, but often not. These faded out halfway down the page as his printer had run out of ink. They were letters to a true range of current and perhaps more forgotten names of varying statures. I wish dearly I still had all of those opening paragraphs.

If there is one final illustration of our time together which captures Sam’s humour and personality, then it is this. I had the pleasure of reading for Sam at our workshop meetings each month. As his turn came within the group he would hand out the sheets I’d copied for him earlier, and I would read aloud his poem at my own first sight of it. This was a surprisingly simple task, as his poems were inevitably well finished, and the metre – though rarely obvious – guided the reader in his task, the fluidity of the line abetting what were often unexpected convolutions of theme. Often I would find myself slightly startled by the narrative turn taken by a poem as I read it. And occasionally I stumbled – and Sam was gracious about this, or would poke fun a little, not precious about my handling of his work. On one occasion he handed out the poem, and as I asked if he would like me to read it as usual, he nodded with an unusual keenness, smiling with his tongue tucked in his cheek. As I read the poem, I realized he had laid me a trap. The poem contained the word synecdoche – a word with which fortunately I am familiar. At the end of the poem rather than his usual ‘thank you’ and request for ‘any comments?’ he leant forward, pen in hand and said ‘thank you— and how did you pronounce that word in line 14?’ and as I repeated sin-eck-doe-key he licked his pen theatrically, and made a mock note on his manuscript saying ‘Ah! Thank you very much’.

In his poetry, his advice and criticism, and his friendship Sam instilled the same combination of enquiry, encouragement, enthusiasm and devilment. He built a community of poets of all types and all calibres around him. I am tremendously grateful for his support and advice, for the loan of his books and his ear, and the pleasure of being the butt of his criticism and his jokes. He was my friend.

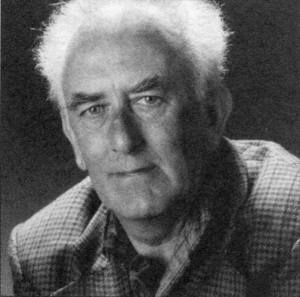

Sam Gardiner 1936-2016

Collections

Protestant Windows (Lagan Press, 2000)

The Night Ships (Lagan Press, 2008)

The Morning After (Lagan Press, 2010)

All available here

Pamphlets

Lincolnshire’s Millennium Poet (Imp-Art, 2000)

The Picture Never Taken (Smith-Doorstop, 2004)

Southumbrian Tidings (Nunny Books, 2008)

Key anthologies

New Irish Poets (ed. Selina Guinness, Bloodaxe, 2004)

The Magnetic North (ed. John Brown, Verbal Arts Centre,2006)

Something Happens, Sometimes Here (ed. Rory Waterman, Five Leaves, 2015)

*****

[1] Fred Johnston ‘Rooting out the Rural’ Books Ireland, December 2000.

[2] Tony Thorne ‘Poetry… Your Very Own Therapy’ (a paper from the 1976 International Poetry Conference) Orbis #26 1977.

[3] Peter Forbes interviewed in Wolfgang Görtschacher & Andreas Schachermayr Contemporary views on the little magazine scene Poetry Salzburg, 2000 p.31

[4] Robert Greacen ‘New Poems 1976-7’ British Book News April 1977, p319-320

*****

Phyll Smith is the founder and co-ordinator of the Nunsthorpe Poetry group in Grimsby. He also teaches film history and cultural studies at the University of East Anglia. He is the author of The Last English Revolutionary, a biography of the poet and political dissenter, Tom Wintringham.

Three Unpublished Poems by Sam Gardiner

THE SORRINESS

The first word I had to learn was ‘sorry’

and not just because everything was my fault,

but people like the world to apologise when

tossed fippences keep coming down tails.

Thorns tore my sleeve for blackberry picking.

Sorry I fell out of Simm’s apple tree

when I heard his tractor, and now my knee

is too poorly to walk to school today.

Sorry about the rain. It’s not personal,

and neither is Towzer’s hatred of cats.

Our aim is always to find a nicer area.

But I will fix the shower. It’s on my list.

Sorry about the high cost of Las Vegas. Typical,

but we can probably manage Majorca again.

You need years of training for ‘Sorry about

the stillbirth. We should never have named her.’

MAYBELL

Maybell wore blue stockings

and Mick red socks, and the love

they shared redefined the word.

Days had shortened the nights

when he took down two chimneys

brick by soot-and-red brick,

long after the smoke had gone,

and with it the smell of burning coal,

and aromatic hazel, and sparky deal,

and a whole family of lost aromas.

The roof tiles were made good

but the chimney breasts remained.

It was Christmas eighteen months later

when he was delivering a boot-load

of old bricks for hardcore that he

drowned while he sat in a crashed car

in a flooded Lincolnshire dyke,

watched by two wet bullocks

who couldn’t tell an unusual death

from a normal human pastime.

People say he was unconscious

or that maybe he took his own life,

decided to leave and took it with him.

But love can be too good to be true

and they had split up six months earlier.

Now, with a hand that wears a black

widow’s ring she picked up in Romania,

Maybell bends painfully over

her scented bath and, old habits

having lately become new endeavours,

pushes a feather of white foam

off a painfully distant ankle.

ANGEL FEATHERS

The cathedral rings the Angelus bell

at noon and Gwen and her parrot come out

onto the balcony to say their prayers.

But now that Gwen is temporarily

laid low by a surfeit of baked lamprey

the parrot comes out and prays alone.

It gives thanks for the incredible air made

to carry the sound of bells, and the wings

that God made specially for His angels.

(The High Window would like to express its gratitude to the estate of Sam Gardiner for permission to publish these poems.)

2 thoughts on “It’s the Way He Sees It: Phyll Smith on the Poetry of Sam Gardiner”