*****

Catherine-Esther Cowie: Heirloom • Malcolm Carson: Winging It • David Ricks: With Signs Following • Bernadette Gallagher: The Risen Tree • David Nash: No Man’s Land • Gastón Fernádez: Apparent Breviary • Maeve O’Sullivan: Where All Ladders Start • Kevin Bailey: Freud’s Graffiti, Collected Poems (1974 – 2024) • Helen Kay: It was never about the kingfisher • Mary Mulholland: the elimination game • Antony Johae: Foreign Forays

*****

Heirloom by Catherine-Esther Cowie. £11.99. Carcanet. ISBN: 9781800174795. Reviewed by Kathleen McPhilemy

Catherine-Esther Cowie’s powerful first collection is tightly structured around her own origin story, tracing the history of her family through the female line from the rape of her great-grandmother by a white landowner in St. Lucia. After the three ‘Prelude’ poems, there are four sections, one for each of the four generations, finishing with ‘Catherine’, the poet. The first epigraph, from Julia Bouwsma, asserts ‘Because this is how you mark a child, make her yours forever. Press your story like a blessing into her still-bruised forehead.’ Cowie’s book invites us to trace a family narrative, to move forwards along a linear chronology whilst recurring to and unfolding that still bruising story of origin, a story which is not simply a personal heritage but also a representation of colonial and post-colonial history.

‘Origin begs for Hymns’, the first poem in the Prelude section, presents the patriarchal founding father, who ‘carried their people to a new sun.’ He portrays himself as a divine master managing slaves, ‘as it pleased me, / they brought forth cane and cocoa … as it pleased me, when I said, / dance, they danced’ but at the same time as a benefactor, founder of culture and language, albeit ‘a bastard tongue’.

Without me they are without jazz,

reggae or calypso tune.

Yet the poem ends in violence and the begetting of a monster: ‘I build a loom in her belly, / spin you, daughter – / complete with claws and fangs and fur.’ This is a peculiar and powerful image, first in the notion of the rapist male spinning, which is usually a woman’s occupation, and secondly, in the bestial description of the child, who is also Maria, the poet’s grandmother. That she is shown as ‘complete with claws and fangs and fur’ seems to reflect the father’s recognition that he has broken the natural law but also the wild rage and capacity for violence that he recognises in his progeny. The next poem again seems to adopt the male colonist’s view of the island women: ‘Too loud for God, the priest / said’, ‘too much colour’. The third poem brings us back to the personal and specific, showing the white great grandfather as entitled and irresponsible, availing himself of young girls in seigneurial fashion:

He swore she begged, didn’t she –

like a mango in a white bowl begs for teeth.

Colour pervades this collection and its symbolic value is apparent in the naming of the great-grandmother as a sixteen-year-old Leda, raped by the whiteness of the all-powerful swan-god, on the kitchen floor. This original sin of god against woman, rather than the Biblical one of woman against god persists in the lives of succeeding generations. However, Leda’s story is more complicated than the simple structures of myth might allow. She produces a child, Maria, freakish in her whiteness, ‘her pale skin / blessing her bastardness clean.’ She then takes up with an English naval captain, but ‘An English specimen, ruddy-faced and balding, / he strung himself up like a fruit. A mango’, an image which suggests that this second white man is himself a victim of the fatal wrongness of Caribbean history, the clashing and melding of two populations, neither of which is indigenous to the place where their history plays out. The strength of Cowie’s collection lies in her willingness to explore this complexity, even to her extending, through Marie, a measured compassion to the founding father and rapist, who seems to have dwindled to an unfortunate end: ‘You were too white to live like that – / In a hut. On the beach.’

Marie seems to find herself ‘a staying man’ although the match is regarded with suspicion : ‘You a butcher man’s son / I a landowner’s daughter. / Some people doh like the sound of us.’ Nevertheless, the theme of violence and mistrust is carried on, as Marie fends off the attentions of men to herself and her mixed-race sisters, then fiercely disciplining her own daughter: ‘I hit my daughter…. She came home after five, What did she expect? You stopped me from being me, she cries. / I tell her, this is what I know, / my hands staving off men.’

In the next section, ‘Daughters’, the narrative becomes more diffused; presumably, these are the children of Marie, but they are haunted by the shadow of violence and the presence of their grandmother, ‘Granny’, ‘Leda, Gwanmanman’

Even after I married,

after she died, she endures.

It seems that the violence endured by Leda and which has led to her madness has been inherited by the daughters, as has the sense of complicity in post-slavery colonialism and post-colonialism.

We ate the fruit Lord

boiled and buttered we ate.

…

It was the fruit of a breadfruit tree.

A tree as old as the first city.

…

Ghost of our first father

…

But we were fed, fed, fed.

The daughters seem consumed by guilt at what their past is doing to their own daughters:

We smashed the platesxxxxxour children saw

we didn’t want them to seexxxxxxxthe breaking

of thingsxxxxxour hands

high-pitched and frenziedxxxxrepeating

our mother’s fists against our faces.

So, finally, we come to the poet, ‘Catherine’. The section opens with a poem where the speaker seeks to reconcile herself to her name, which in its duality, reflects her conflict, “I walk the plank between two names’ but which ends in a confrontation with and acceptance of her complex heritage, ‘I will not knife the French and English / out of my tongue, this heirloom, cruel and sweet. / My white ancestors roll, roll, roll – / I’ve been sewn into their line.’ These poems are troubled and questing, searching for a meaning from her history, not only to find peace and mental strength to lead her own life but also to enact the process of ‘unforgetting’ which can lead to a more honest understanding of history. Cowie’s language incorporates Kwéyòl, the St Lucian creole, which in its mixture of English, French and African languages, exemplifies the intricacy of this past.. The poetry ranges from the highly imagistic and literary to street talk, as in ‘My Englishman’. In these final poems, we can see the poet bringing the two primal ancestors into the light, Leda, ‘Mummy, Mummy, Mummy.’

Leda, look at me,

I am the colour

of your dark root

yet I live,

eat,

send for you.

and the first father, whose name we are never given:

I call you monster.

I call you father.

How this song blues the kitchen floor

bloodies our feet.

This is a rich, coherent, though sometimes bewildering, first collection. The blurb describes it as ‘beguiling and cathartic’. I’m left wondering, after such catharsis, what next.

Kathleen McPhilemy grew up in Belfast but now lives in Oxford. She has published four collections of poetry, the most recent being Back Country, Littoral Press, 2022. She also hosts a poetry podcast magazine, Poetry Worth Hearing https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/kathleen-mcphilemy.

*****

Winging It by Malcolm Carson. £10.00. Shoestring Press. ISBN: 9781915553690. Reviewed by J.S. Watts

I’ll admit I was misled and then taken by surprise by Malcolm Carson’s latest collection Winging It, and I mean that in a totally positive sense. The first and title poem, Winging It, is a charming, lightly humorous character piece about a minister who keeps pigeons:

He loved his pigeons, almost as much as serving

his Lord. He would attend to them

when his other flock were grazing on life.

The ending of the poem involves a wedding service and pigeon poop: ‘marrying his twin passions.’

The next poem, ‘The Church of St. John the Dentist’, is another humorous piece written: ‘On misreading the church’s name obscured by leaves’. And so it goes on: Agnes – a brief monologue by ‘boring’ Agnes from David Copperfield; ‘Mr Wordsworth is Never Interrupted’ – a delayed meeting between the great man and a certain Mr. Keats; ‘Le Salon Des Refusés’ – two writers: ‘proud conspirators/ in our sense of inverted celebrity’.

I therefore came to the premature, and wholly wrong, conclusion that this was a book of light verse: technically proficient and cleverly constructed, filled with dryly amusing vignettes and lightly entertaining in small doses. Of course there’s nothing wrong with light verse, but it’s not necessarily my thing, and, like sugary drinks, you don’t want, or need, to consume them all at one go, which, as a reviewer, I was going to have to do. However, I was wrong. Yes, there are some dryly humorous poems, but as you progress through the collection, the tone gradually deepens and darkens. The lightness of stylistic touch remains, but the characters in the carefully crafted vignettes take on darker undertones. Their wants and desires become less overtly amusing, as in the somewhat mournful ‘Le Viel Amant’:

Despite his better judgement,

knowing he was an old fool,

he couldn’t help but think,

maybe this time, maybe

this one last time.

Then there are a number of structurally simpler poems where the exterior character of the narrator takes a back seat and it is the voice of the poem that comes through, even if it is ostensibly voiced by an independent speaker. An example of this is the poem ‘Riding With Geese’:

Their flight across the wood

always stops me, listening

to their chorus, see broken

echelons back and forth

from estuary roosting,

winter field feeding

Or the simple but haunting ‘Give Me A Stand of Trees’, which I here quote in its entirety:

Give me a stand of trees,

he said, on a Northumberland knoll

bare against the dying sun.

Let me watch sky bleed orange

into night. No prayers,

no hymns, just

a stand of trees.

This is directly followed by ‘Among Pines’, which echoes with the poem that precedes it:

Enough for me to settle for

the shadows among silent pines.

By the end of the collection we have drifted into poems that sound a lot like memories. ‘It haunts me still’, the opening line from ‘Hate’ or: ‘I’ll always remember Delmenhorst, arriving at night,’ from ‘Delmenhorst’. There are poems centred around Grimsby and subsequently Northern Ireland (according to the back cover blurb: ‘Malcolm Carson was born in Cleethorpes… He was educated there and subsequently in Belfast where he moved with his family’).

There is still room for humour, but also the gentle sorrow of, and nostalgia for, times past and, when circumstances warrant it, the much darker note of bad memories. In Northern Ireland, the shadow of The Troubles is present even on the sunniest of days. In ‘Pulling Out of Belfast’ during a family trip: ‘out of Belfast shipyards’, family: ‘incredulity at kerbstones/ in tricolour’ leads to the observation: ‘ ‘A lot’s changed,‘ I say./’And nothing’s changed.’ ‘ In ‘One Who Knew’, the casual, thoughtless donning of a French beret takes on a much darker significance:

I found berets had been worn that day

in another place over the mourned, and was advised

by one who knew that it hadn’t been the best

the night before to wear my own.

In ‘Ballyhackamore 1961’ the potentially risible experience of a barbarous barber:

my cousin told me – no use,

of course – he’d gone there once,

but never again once blood

was drawn

ends on a note of black humour linked to The Troubles when, on a return visit:

I looked for the barber’s, Paddy Lamb’s

and Din’s but they’d been bombed out.

I was sorry about the pubs.

This is a collection of dark and light, humour and sadness: poems that entertain the intellect with tall tales, but are not afraid to reach down into the deeper and sometimes darker waters of recognisable reality and emotion.

J.S. Watts is a poet and novelist. Her poetry, short stories and non-fiction appear in diverse publications in Britain and abroad and have been broadcast on BBC and independent radio. Her published books include: Cats and Other Myths, Songs of Steelyard Sue, Years Ago You Coloured Me, The Submerged Sea, Underword (poetry) and A Darker Moon, Witchlight, Old Light and Elderlight (novels). For more information, see her website https://www.jswatts.co.uk/

*****

With Signs Following by David Ricks. £11.99. Two Rivers Press. ISBN: 9781915048196. Reviewed by Colin Dardis

When presented with a first collection which has culled from three decades of writing and translation, it’s reasonable for the reader to expect the poems to have crystallised and refined over the years. In the afterword, A. E. Stallings describes the poems as “unabashedly serious, learned, and well crafted”. The first two claims are certain; as for the third: results may vary.

‘Prelude’, the opening poem, set apart from the rest of the text, is a promising start, using form and rhyme to describe the surprise of an avalanche in a manner that offers an observer’s wry bemusement rather than the usual panic. The strength of the poem lies in this unexpected tone, and Ricks takes a similar approach to other subjects elsewhere. Gray’s Anatomy is reimagined as a sex manual. A spinet piano becomes ‘a tiny coffin’.

It’s tricky to identify a clear theme across the collection, and indeed there doesn’t necessarily have to be one for a book whose gestation has been over thirty years; however, the fragility of life is a concern that certainly creeps in. ‘Incident’ remembers the Darkley Gospel Hall Massacre of 1983 during the Troubles in Northern Ireland. Ricks presents a simple but disturbing contrast of sounds:

The worshippers had a tape recorder running.

At the verse, Are ye washed in the blood of the Lamb?

We hear the sound of automatic fire.

It’s a standout poem, Ricks again finding rich ground in tragedy for his work. However, the above are unfortunately meagre charms dotted throughout the collection. A series of ekphrastic poems offer images and narratives that barely limb pass the borders of the picture frame onto the page, and do nothing to stand alone as coherent pieces. It is only in ‘Unpainted Pictures’, inspired by the works of Emil Nolde, that the writing transcends this limpid approach to something more stirring, with a tone of admiration for Nolde still progressing with his work after the removal of his work from museums:

to seek those matted

fields brushed

by sluices

swept by

clouds

washing

the world with colour

that runs

even as we sleep

Given that Nolde was a support of the same Nazi regime that condemned his paintings, it’s curious that this poem is present alongside other pieces that outrightly exploring and commiserate over the Jewish plight. ‘Untitled’, by dint of lacking a title and never directly naming its subject, only referring to the vague ‘they’, reflecting the attempt to strip the Jewish of their homes and their identity. ‘Ethnic Cleansing’, a mere six lines, staggering in disbelief at the attempt to wipe out an entire population: ‘The century | Had done away with sanctuary’.

Elsewhere however, there are poems that rely too much on familiarity with the subject matter to stir any interest or empathy from the reader. ‘Angleton’s Names’ is a series of six pieces riffing on the various nicknames of the CIA officer and spy James Jesus Angleton. One of the nicknames is ‘The Poet’, which offers the only interesting thing in the otherwise dull series, in that it mentions the T.S. Eliot poem ‘Gerontion’. Angleton once described the world of espionage as a “wilderness of mirrors,” a phrase he borrowed from said poem, although the poem is more infamous for its antisemitic portrayal. Again, as with Nolde, it seems as if Ricks is revelling in this intertextual apparent contradictions.

‘Angleton’s Names’ gives us the lines ‘He can remember his own lies’, presented as ‘almost a definition of the poet’, and elsewhere, Ricks plays with this self-deprecating. ‘The Full Professors’ is only two lines, its brevity in contrast to the self-important of scholarship: ‘we can cite, but we can’t see’. However, this approachs ultimately backfires. In the closing poem,‘Cycladic’ describes a number of statuettes ‘Without mouths or eyes, || ‘Inviting us to complete | The missing features’. This could be read as almost self-referential, in that the reader often has to do a lot of work themselves to ascribe meaning onto some poems. Poems about the various London abodes of Ugo Foscolo, the possibility of Poor Tom’s penchant in King Lear to wear lots of clothes, of a photo from Thomas Burton’s book, Serpent-Handling Believers, will send you running to Google, scrambling for context.

Ricks is clearly well read and his range of interests varied; however, as times, his subjects come across as the intellectual posturing reminiscent of the schoolboy bluster found in the more dreary passages of Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. The style can be neatly summed up through one of Gandhi’s sevens social sins: knowledge without character. The crowning example of this is found in ‘A White Officer in 1945’ takes place during the Russian Civil War, but instead of adding to the pantheon of existing great war poems, we find the subject’s with ‘his heart’s flag permanently at half-mast’, resorting to drink ‘which only makes him sad’. The triteness speaks for itself.

Colin Dardis‘s recent poetry collections include with the lakes (above/ground press, 2023) and What We Look Like in the Future (Red Wolf Editions, 2023). A neurodivergent poet, editor and sound artist, he currently co-hosts the Poetry Poetry open mic night in Belfast, and is editor of the poetry blog, Poem Alone.

*****

The Risen Tree by Bernadette Gallagher. €15.00. Revival Press. ISBN: 9781738499502. Reviewed by Olga Dermott-Bond

Reading this collection is a quiet, meditative experience. Gallagher, through her sequence of nearly forty-one tiny poems, creates a hymn of praise for life and the present moment, balanced with deep acceptance of death. The Risen Tree is an observation of becoming and unbecoming. This is poetry steeped in both the language of religion and the natural world.

The titular poem is the first we read, and within it are the seeds of many of the themes, preoccupations and observation of form we encounter. Immediately, the title conjures ideas of both suffering and resurrection, and the poem describes an everyday encounter on a jog when she notices: ‘a tree / fallen, branches growing straight up.’ Here we have death and life present in the natural world. In the midst of the poem, the rhythm of the runner slows:

I think of all the dead below us

feeding us

sustaining us

wanting us to go on.

Caught in the forest Gallagher reflects on the intricate relationship between death and renewal, and I felt I was being invited to do the same.

One striking feature of The Risen Tree is the chosen form: each poem works as a triptych, having a title (at times beguiling) an extract from one of the Old Testament Psalms and the poem itself, which is brief, reminiscent of biblical verse. There is interplay between all three, for example in the poem ‘A Moonless Night’ the epigraph is taken from Psalm 39:6: ‘no more than a shadow’ and in just nine lines of poetry Gallagher works with both the title and the Psalm to include images of permanence and transience, how whether through ‘brushstroke’ or ‘chisel’ the act of creation reinforces our existence, yet, like the moon referenced in the title, our names will be ‘erased’ after ‘shadows / of the last to know us / are no more.’

This collection is full of the natural world, as tomato plants, heather, rain, mushroom, spinach, kale appear in abundance as everyday miracles and reminders of our connection to the earth. Through keen observation and enjoyment of nature Gallagher seems to hold both the spiritual and natural world in her skilled gardener’s hands. In ‘Winter Food’ the poet has a silent conversation with the plants that are ‘past their best’:

Each morning I gently press a tomato to ask if it is ready.

some stay hard longer than they should

not yet ready to go.

As well as plants, animals – and particularly birds – flock the pages. In ‘A Thaw’ after a melancholy extract from Psalm 25:16 we read how ‘the crows perch in line, our ancestors / gaze down.’ In this wintry poem, the birds give comfort if we can remember that we are ‘overseen and overheard / understood.’ These minute creatures flit throughout the collection, never still for long.

Indeed, a striking feature of this collection are the late seasons often shown, autumn and winter. These seasons that bring endings, death, coldness and sparseness seem to dominate with their own particular beauty. Frost, coldness and winds creep in round the edges of many poems, giving a stark beauty to so many moments. In ‘Storm’ there is an acceptance of even the roughest elements:

Inside my home of stone the wind

wraps itself around me

and calls at my window

asks me to come in

The seasons act, perhaps, as parables for later years in life, of hard-won wisdom and of loss.

I was also struck with how most of the collection is written about the present time, written in a present tense of intense observation and mindfulness: everything in nature is happening now, a fields glistens, the birds hover, the frogs gather underwater. This gives the book an immediacy and quiet vibrancy that makes us slow down and appreciate the small everyday miracles as the poet observes them. Against these poems of the here and now, a few stand out in capturing a poignant past. ‘Legacy’ recalls a childhood school room, and brilliantly conjures up a troubling portrait of a young child surrounded by stifling impact of tradition through the ‘iron’ legs of a table, ‘birds and fish hung on the wall’ and ‘the dark imprints of words’, along with the implied violence of ‘stings of rulers’ that are all skilfully included. This serves to emphasise the vulnerability of the three year old child and the long-lasting legacy of abuse this experience makes across a lifetime. However, ultimately the book aims to reconcile and overcome grief, sadness, trauma which is never explicitly named. Much later on in the collection, In ‘Today’s lesson’ Gallagher’s solution is to ‘forgive.’

I think this collection will resonate with me for a long time, in the same way prayers and hymns learnt in childhood resurface when perhaps we had thought them forgotten. The Risen Tree begins with an epigraph from Sappho where it is written, ‘you will go your way among dim shapes. Having been breathed out.’ This acceptance is brought full circle in the final poem where the poet challenges us to view death as natural and wonderful as a life beginning. In ‘Lifeline’ she challenges us with a final imperative: ‘imagine delaying a birth.’

Olga Dermott-Bond FRSA is originally from Northern Ireland, and lives in Warwickshire. She has published two pamphlets: apple, fallen and A Sky full of strange specimens. Her first full collection Frieze, published by Nine Arches Press, was featured in The Guardian. She has won competitions including the BBC Proms poetry competition, Welshpool and Strokestown International prize and was highly commended in Forward Poetry prizes 2024. She is currently a managing editor for Irish poetry journal Dodging the Rain.

*****

No Man’s Land by David Nash. €12.50. Dedalus Press. ISBN 9781915629210. Reviewed by Nick Cooke

In commenting on the decision to award this volume the Seamus Heaney First Collection Poetry Prize for 2024, chair of the judging panel Nick Laird described it as a ‘book of return and renewal’, with author David Nash – a County-Cork-born poet who lives between Ireland and Chile and is the author of a 2022 pamphlet entitled The Islands of Chile – able to combine an ‘insider’s easy familiarity and an outsider’s fresh perspective’. In this Nash might be said, loosely speaking, to be following in the Wordsworthian tradition of returning to a familiar place and seeing it with eyes anew, although previous emotions are recollected not always in tranquillity but with an arch, often tongue-in-cheek wit that constantly questions assumptions and potential prejudices.

The lessons learned from experience can sometimes be life-saving, as exemplified by ‘Slievemore /An Sliabh Mór/The Big Mountain’, whose bilingual title (so to speak) highlights the cross-cultural basis of this poetic voyage, while the casual brutality handed out to foolish neophytes reflects Nature as a force less than fully akin to Wordworth’s view of it in ‘Tintern Abbey’:

Every summer, some mainlander

would mistake weather for climate

and scale it in a dry spell,

unready for the heavy hand of mist

that inevitably fell and swept

them off it like whatever was left

of the bread from the breakfast table.

The volume has much about the power of water, with ‘river(s)’ revealing more of the uncompassionate, indeed ruthlessly cold-hearted natural world, acting as it does like an efficient functionary:

Should any of us drown (our young, our best even) the river

must be considered to have done its duty.

Overall, one gets the sense that a major upshot of Nash’s wanderings, both geographical and philosophical, has been a reinforcement of his belief in our infinitesimally small place in the universe. However much we may seek to acquire some measure of control over nature through education and its boons – for instance the ability to frame rivers as metaphors or personifications of human traits – the stark reality is that ‘The first word is water, and the last word is water. What the / river says, goes.’ One can almost hear Dr Johnson adding, ‘And there’s an end on’t’.

I greatly admired the way in which many of these poems twist back on themselves, as if including the poet himself in an operation of self-scrutiny, as well as a more outward warning against any form of complacency when thinking about life, nature, politics, culture, and so forth. It’s no coincidence that the words ‘reverse’ and ‘reversal’ are used several times, or that the collection is shot through with gripping paradoxes and contradictions, as in these lines from another ‘water poem’, ‘Turlough’ – itself an oxymoron, since ‘tur’ means ‘dry’ and ‘lough’ ‘lake’:

the lake you see before you now is

the lake you don’t

inverted, the water table

with its legs in the air,

an underground overed,

a frown upside-downed.

In Nash’s vision, emotions are never simple. Love is shot through with suffering, and later we are reminded that, if loneliness and isolation dominate a life, the power of feelings does not always translate into a higher level of human connection, when Nash tells his sister’s children

I wish you never to hear your own heart

beat into the mattress, bed frame, beat across the floor,

advance through the house with the thirst of electricity,

making sing its starscape of nails,

and then slink back along those same branches of electricity,

back through beams and doorways, back across the floor,

come back empty-handed, the heartbeat returning to the father heart.

This is one of the collection’s most memorable passages, and perhaps the most haunting example of the frequent back-twists.

As Eliot put it, ‘Words strain, crack and sometimes break (…) will not stay still’, and in Nash’s book (in both senses of that phrase), the pervasive uncertainty extends to language, which often loses its own grip on intended communication, due to inherent ambivalence. This is amusingly pointed up in ‘Imaginary Farmer’, when the eponymous farmer tells the poet/speaker ‘You don’t know shit’, and it turns out he is referring to actual excrement rather than the more idiomatic meaning of the phrase (‘You wouldn’t know the dropping from the bird that drops it’ – which incidentally I took to be a deliberately bathetic allusion to Yeats’ ‘How can we know the dancer from the dance?’). Nash is ever-aware of linguistic slippage and blurring, as when he highlights how an utterance can change meaning, depending on the stress accorded to different elements –

…like those pre-sleep

alarm bells

that sometimes

ring: what might have

been, what might

have been, what

might have been. (‘Snow Drop’, with a possible nod to Eliot’s ‘rose-garden’ passage in

‘Four Quartets’)

Similarly, punctuation and/or spelling can radically affect one’s understanding of a phrase. At the end of ‘Professional Earth’, Nature is suddenly seen as inextricably human in essence – ‘forget you’re nature’ – where we might of course expect ‘your’, with a completely different meaning.

On occasion Nash deploys his skill with words for humorous effect. For instance, in ‘Fás Aon Oiche’ (‘One Night’s Growth’), the use of the formal accusative relative pronoun amusingly exposes a lover’s infidelities:

I am monster-green by psychology

so I can’t help it if I didn’t take it well

when it dawned on me where you’d been

and whom, more to the point, you’d been in.

Nash’s verbal dexterity includes some delightful, chortle-raising similes (viz. ‘they detonate sperm like champagne / in the cup winners’ dressing room’), and an occasional tour-de-force rhyme, as at the end of ‘Slievemore’:

a scattering of Catholics at sea.

Not just any mountain. The.

Nonetheless, the playful undercurrent does not diminish the book’s serious purpose, and I’d agree with the back-cover blurb when it claims ‘at its heart No Man’s Land is …about loss – the loss of language, knowledge, nature and wilderness that affects all of us’. The final poem, ‘Why You Should Really Think About Rewilding’ opens by parodying a tour guide’s style – ‘We are standing / in what used to be / our forest’ – before outlining, with almost terrifying conciseness, the area’s decline through ‘some spailpin rot or / spore of fungus’ that developed into a fatal condition, leaving a ‘stump-scape / no man’s land’. That ‘stump-scape’ forms a nice counterpoint to the earlier, smoothly hyphen-free ‘starscape’, with the jarring stumpiness reinforced by the consonant cluster either side of the jagged hyphen.

Yet the conclusion, like the book itself, is less negative as might be thought, because in time – a lot of time, admittedly – the forest will regrow itself, as long as we humans, once we’ve set the rewilding ball in motion, stay out of its way: ‘…you needn’t lift a finger / it is its own device.’ Ultimately, we once again have to concede, and roll with, our own lack of real agency, trusting to the uncontrollability of nature and the wildness of germination:

What I’m saying is

take a chance on it.

The seed is reckless.

In conclusion I find I can do no better than quote Francis Spufford, who has described Nash’s debut full collection as ‘a lyric reckoning with the rural landscape of home, by a queer Irish poet returning quietly bereft to County Cork, and deploying a dizzying formal inventiveness to take in what was once familiar.’ I would only hazard a slight quibble with ‘quietly’, preferring ‘wryly’ in recognition of the witty undercurrent on display throughout.

Nick Cooke has had around seventy-five poems published, in a variety of outlets, including the inaugural issue of The High Window, Acumen, Agenda, Dream Catcher and London Grip. In 2016 his poem ‘Tanis’ won a Wax Poetry and Art contest. In addition, he has published around thirty-five poetry reviews and literary articles, as well as several short stories.

*****

Apparent Breviary by Gastón Fernádez, translated by KM Cascia. World Poetry. £19.99. ISBN: 9781954218345. Reviewed by Ian Pople

Gastón Fernández Carrera was born in Lima, Peru in 1940, which he left in 1969 to live in Belgium, where he lived the rest of his life. After a doctorate in art history, he taught the subject, mostly in Brussels. He died in 1997 having published four books on aesthetics and a travelogue. He published poetry and fiction in Spanish until the end of the eighties when he started to write in French, full time. As the introduction also notes, Gastón’ complete literary work in Spanish consisted of two manuscripts, the first, the book, Apparent Breviary, under review here, and the second, Apparent Stories, consisting of 33 prose pieces. Both these books were published in Peru. However, two complete issues of one of Peru’s leading literary journals were devoted to Gastón, and his reputation in Latin America.

Gastón (and that is what he seems to be called universally) has been linked to the ‘neo-baroque’ movement in Latin American letters, and Gastón, himself, corresponded with leading members of that grouping. One such writer defined the neo-baroque as a process of ‘obliterating the signifier of a given signified, but not replacing it with another, but rather by a chain of signifiers which progress metonymically and which end by circumscribing the absent signified, tracing an orbit around it.’ Make of that what you will. But what remains in the page of this book are a range of one page, open form poems, in which trajectory and linearity usually remain absent. As KM Cascia comments in their introduction, ‘There’s simply too much white space to fall into. … You wonder if the poems may, in fact, actually be the white space, with the words there just to shape it. To draw attention to the “absent signified” mentioned above. Which is the (apparent?) absence of God.’ Cascia goes on to comment about ‘the overtly religious language,’ in which, Cascia feels, so much of the writing is couched. There is, of course, religious language and religious language. But, perhaps, on this side of the Atlantic, where so much of our religious discourse may be couched in the legacy of the King James Bible or the Book of Common Prayer, we might be forgiven for asking what Cascia means by religious language.

As noted, Apparent Breviary, consists of 100 numbered poems, each of which fills a single page. As such, the open form of these poems makes this book very difficult to review and Cascia is perhaps to correct to comment that it feels as though the words shape the space around them rather than the other way round. A poem may consist of between twenty and forty words spread over the page. It is as though a poet such as Rae Armantrout were even more minimalist than usual and even more likely to spread those words. And Gastón is likened, here, to both Celan and Emily Dickinson although it feels as though both of those poets were closer to the traditional lyric than we find in the pages of Apparent Breviary. Gastón, himself, writes in poem 46, Write: time an object in space / with no guilt / with no line / with no poem. At wonder’s side there will then be nothing’ Thus, Gastón, undermines his own activity in the moment of its conception. Well, he would if the rest of these poems didn’t exist. And, perhaps, too, they suggest to the reader why Gastón’s oeuvre is so confined. We might think that such undermining is, in the last resort, constricting even, self-defeating. You can only carry on this kind of technical choice and attitude for so long; at which point, the poems themselves become a kind of self-dissolution.

The phrases I’ve quoted are spread over the page and, thus, make reviewing seem a kind of debasing. Cascia’s idea that the words, in effect, shepherd the white space means that the poem on the page is more a kind of experience than a reading. Cascia’s comment that the ‘subject matter’ of the poems is the absconded God, and that the title of the book, Apparent Breviary, a book containing the liturgy for a religious to observe the seven canonical monastic hours, suggests we have a book which almost attempts to create the experience of a negative, apophatic theology.

Of those 100 poems, several, but not all, address a ‘Lord’ directly. The opening poem in the book is as follows, with further apologies for subverting the presentation on the page: ‘Divide the veins / I see is less accessible than / depth / of air / from my place / I’ve seen that indeed air has no / velocity. / Then air, Lord.’ We might plausibly suggest that, for Gastón, accessing the veins is more difficult than accessing air. And if the book concentrates on the absconded God, then the veins indicate the ‘absent signified,’ that is the absconded God, such that it might be easier to find the depth of air, which at least cannot abscond since it has no velocity. Such a treatment might be ripe for inclusion in Private Eye’s ‘Pseud’s Corner.’ And this is the problem with trying to find paraphrasable meaning from this kind of writing. The reader can project a meaning onto the text, but it is always likely to remain a projection.

This is poem 41, with further apologies for presenting the words this way: ‘To walk with everything. / Lip / Line / Hollow. / Around air / books, / another. Name the wind after / someone, direct / gestures toward. / (Arrive / behind. Reproduce / day / ribbon / body)’ We might conceive that the writing is an attempt to show movement as a kind of linearity where ‘line,’ ‘air,’ ‘direct gestures toward,’ ‘arrive behind,’ and ‘ribbon / body’ attempt a kind of mimesis of that linearity. At the same time, linearity is undermined by phrases such as ‘lip,’ ‘hollow,’ ‘books,’ ‘reproduce day’ and ‘body’ present that mimetic linearity is subverted by seemingly solid objects. In fact, then, if the reader ‘buys into’ the writing, it is the range of contradictory ‘experiences’ within the text that Gastón so skillfully yokes. And the white space that is so much of the page, also supports the subversions; the eye must move across the page and thus loses track of linearities that it might perceive.

This is a kind of writing that is designed to make the reader uncomfortable. It is relentlessly questioning, above all of itself. And that is not to take into account the difficulties of translating this kind of work; about which the translator, Cascia, is somewhat self-conscious. However, the final product has a particular sense of the substantial about it. The mind of Gastón may be obsessed with the absconded God, but his commitment to recreating that experience results in writing that bears constant rereading. If Celan is still the apotheosis of this kind of practitioner, Gastón runs him a close second; there is something almost eerily compelling about this book.

*****

Where All Ladders Start by Maeve O’Sullivan. www.albapublishing.com. 16 Euro. ISBN: 9781912773671. Reviewed by Patrick Lodge

In his “Some Reflections on the Arts”, W. H. Auden wrote that “Art is our chief means of breaking bread with the dead”. The Irish poet, John Montague, recalled this quote in a discussion but replaced ‘art’ with ‘poetry’. It is highly likely that Maeve O’Sullivan would agree with this misstatement. In her poem ‘Shadows Pass’, set at the Glandore Standing Stones in West Cork, she riffs on Montague’s poem, ‘Like Dolmens around my Childhood, the Old People’, a poem which Montague described as “riddled with human pain’ and which explores the dead neighbours that he grew up with and which ‘trespassed on my dreams’ until, at Glandore’s neolithic stone circle, he was able to slough them off, ‘I felt their shadows pass’.

There is a lot of the dead, friends, relatives and relationships, in this collection – ‘A fair few of my tribe are ghosts now: / father, mother, sister, friends and a slew / of aunts and uncles’(‘Ghost Train’) – but never once does this ‘abacus / of lost ones’ get morbid or macabre. O’Sullivan may write that ‘it is hard to avoid the foggy pool / of gloom’ (‘Shadows Pass’) but this is not a tone which pervades the collection – serious topics are dealt with seriously, but almost conversationally. Thus, ‘Shadows Pass’ may be rooted in loss but clever wordplay and an overarching hope makes it uplifting; we may meet again with joy those passed on, though hope seems as much influenced by the neolithic circle as any contemporary faith: when we do, we’ll ‘dance with those who have died / in the shadows of the dolmen’s capstone’.

There is a strong tradition in Irish culture of female- ed mourning, of the ‘caoineadh os cionn ciorp”, the keening lament for the dead which is as much celebration as lamentation. This is the spirit in which O’Sullivan, especially in the first section, deals with loss. There is an Irish proverb which translates as “death leaves a heartache no-one can heal; love leaves a memory no-one can steal’ and in a number of poems O’Sullivan hints at the truth of this. Irish poetry often acknowledges the enduring presence of dead family members and close friends walking with the living; death as transition not an end. ‘Kilmainham Goal’ is a tender poem written in memory of her grandfather and based to some extent on letters he wrote while interned during the War of Independence. Similarly, O’Sullivan extends an invitation to her mother, dead nine years, to accompany her and offer advice: ‘Walk with me, mother, all along this strand / we’ll surely sort the world out, hand in hand.’ (‘July Morning, Bettystown, Co.Meath’).

In ‘Leinster Lineage’ this continuity within the family – dead and alive – is well-handled and even extended. The poem starts with a reflection on the ‘dark-eyed’ people who built the Neolithic passage tombs of the Boyne Valley – we have the objects remaining but can know little about the builders – and then segues into her dead grandad, along with his wife and ten children also entombed, and whose life stories can only be looked for, like the Neolithic, in signs: “in letters, photos / and the Leinster landscape’. The poem delicately looks for insight, some understanding in this continuity. Similarly, ‘Civil Servant’, explores another grandfather who died when she was nine months but “held me close when I was small’; this contact is sufficient, it seems, for the enduring relationship to be made and the family continuity to persist.

Several of these family-related poems are written as villanelles and evidence O’Sullivan’s confidence in using a variety of set forms – including some well-realised specular poems – and experimentations in the line of concrete poetry. She is indeed closely associated with Japanese poetic forms and has published widely in the haiku form. This collection is similarly eclectic with sequences of senryu and several haibun which blends formal haiku with prose. O’ Sullivan handles this well and makes full use of the potential of the haiku for both thematic and emotional focus. ‘Through Hollow Lands and Hilly Lands’, from Yeats’ ‘The Song of Wandering Aengus’ which is referenced within the poem, is a delightful haibun where O’Sullivan is lunching with her elderly father after visiting her mother in a nursing home and reflects, with humour, on the possibility of reading Yeats at his funeral. Here the closing haiku carries gently the full emotion of a reflection on mortality: ‘ his blue eyes / milky with morphine… / not long now’. This near understatement seems characteristic of O’Sullivan – there is almost a naiveté to her poetry which is good. She does not strive for effect, does not self-consciously perform as a poet, but writes it, with careful craft, as she sees it, and often with a telling, succinct summative image; a visit to Clonmacnoise closes with the sparkling lines ‘Leave all these ruins / behind, your last sight / a charm of goldfinches’ (‘Clonmacnoise’).

Close friends are touchingly remembered in poems such as ‘Sonnet For Mamo’ – Mamo McDonald, poet and feminist activist. It is, though, the random encounters which provoke O’Sullivan to close observation that reveal her essential humanity and demonstrate the axiom that poetry can be made from anything. A group of wild swimmers are celebrated: ‘The Swimming Women / soap pendulous breasts and sagging bellies, // push big bums into bigger knickers’ (The Swimming Women’). A chance encounter with a shop assistant in Portugal elicits the admission that she had ‘tried suicide a few times’. O’Sullivan – unsentimental, frank – offers a ‘lame’ response but nails the emotional content in a concluding, displacing, haiku: ‘posing on the girder / the boys jump from the tall bridge / into the Douro’ (‘Never Get Old’). John Montague once said poetry opened a hinge “to the unconsciousness of other people with whom you are connected’ and O’Sullivan demonstrates this truism.

O’Sullivan seems an honest poet and her own relationship issues provide suitable material for mischievous and considered poems. Section III opens with a grounded, tone-setting, haiku: ‘date no show… / the apple strudel / tastes just as good’. Some are quite quietly erotic – ‘Plutonic’, punning on platonic and referencing the underworld, offers a poem that could be read in ways that transcend the action of hot gases on rock. No soppy sentimentality here – a candle-bearing visit to the relics of St Valentine (actually in the Carmelite church in Dublin) follows more Chaucer’s line on the patron saint of lovers, “when every fool cometh there to choose his mate” with the closing comment, ‘single booking: / another room / without a view’. (‘Saint Valentine’).

‘Childless’ explores a mini-history of previous partners and the happenstance that led to having no children – again, emotionally open and not remorseful, but the punchy closing haiku carries emotional heft: ‘concert interval – / my friend’s hands entwined / with her granddaughters’.

O’Sullivan’s collection title is linked to the W. B. Yeats poem ‘The Circus Animals’ Desertion’ where the aged poet bemoans the diminishing of poetic inspiration; ‘ Now that my ladder’s gone / I must lie down where all the ladders start / In the foul rag and bone shop of the heart.’ O’Sullivan probably doesn’t consider herself another Yeats and, indeed, this engaging collection suggests no lessening of poetic inspiration but, like Yeats, she has dug deep in the ‘foul rag and bone shop of the heart’ and produced a collection that both engages and interests and also leaves the reader hopeful. Indeed, in the closing poem – ‘Foul Rag and Bone Shop’ – O’Sullivan directly addresses her heart – and the poem is structured as a heart – in an apology for ‘past partners, blithe boyfriends…and the odd one-month wonder’. She suggests a respite ‘amid the rags and bones’ but remains ever hopeful that the ‘wait for a ladder / to extend / again…’ will not be a long one. As will many of her readers.

Patrick Lodge is an Irish citizen with roots in Wales.. His work has been published in several countries and he has read at poetry festivals across Europe. Patrick has been successful in several international poetry competitions and performs with the Poets of Esnoid. His fourth collection, There You Are, is due for publication in 2025.

*****

Freud’s Graffiti, Collected Poems 1974 – 2024 by Kevin Bailey. £12. Day Dream Press/Stavaigers. ISBN 9781916478923. Reviewed by Patrick Osada

The title of Kevin Bailey’s Collected Poems, Freud’s Graffiti, is not a fanciful one. Kevin writes, “The six years spent studying psychology must have influenced my thinking and creative ‘dynamic’ in some way, and therefore a part stimulus to the baring of my inner demons and angels through poetry. But the poems are ‘art’ not ‘therapy’ – and I hope sufficiently ‘universal’ to resonate at some level with the reader.” Many of his poems are to do with love and relationships. His fourth collection, Surviving Love (2005) focusses on intense love affairs, some in graphic Lawrencian detail, while others are set in a more introspective and philosophical vein.

Unlike many ‘collected poems,’ the arrangement of the contents of Freud’s Graffiti is not set out by published collection. Consequently, although many of the poems from Surviving Love can be found in this latest book, the section of translations dedicated to Sappho has not been included (this seems a pity as it offered a contrast – love through a woman’s eyes.) However, the section headed Arthur and Amélie is retained and, in A Solitary Boy, Kevin explores sexual awakening:

In the church, a solitary boy

practising cantata – his notes

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxskittering

amongst the old rafters. The dangling bell-pulls.

The oscillating ropes.

In the heavy air, a Magdelana has undressed.

Plaster-white breasts

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxrubbing

through a chemise of dull blue paint.

She steps down from her plinth. Shakes

her hair. Gold flakes

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxin a shaft of light.

A voice, breaking.

And from the section, Wanderer, the poem Yerma recalls a liaison…

Gathering the scent of almond blossom

on this still, moonlit, March night;

I remember you, and the slight curve

of your flank, and the fresh smell

of white flesh pressed by my weight —

in a depth of sheets met, this odour

of love made then — and here, a breeze

risen ghost; the affects of cursed body

and sense, that knows itself, yet aches;

growing satiate — but incomplete.

From the section, A Treading of Uncertain Ways, the theme of ‘Pomegranate’ is desire …

She was just so ripe – there is no other

word to describe this fulness of flesh,

breasts, thighs, round face, and bright

eyes – she was just so ripe, and ready

to burst like the pomegranate, held up,

eclipsing the sun: its light, a trans-

luscent pink – as she is naked… I bite:

seeds and juice from this little fruit

on my lips, and, as always, afterwards.

In the section, Freud’s Graffiti, the analytic eye of the psychologist considers the word Pirouette…

Pirouette. A lovely turning word.

Good on the mouth and tongue.

A pleasure of a r t i c u l a t i o n…

The tutu-ed dancers in white:

their slender legs teetering

on the edge of collapse…

The khaki body spinning round

spread by that raping velocity

as the bullets hit…

The arts of life and death – like these

contrasting pirouettes, stilled by the

darkening stage, or receiving earth.

Later, in ‘George 1960-1980’, there is a disturbing scene from a Psychiatric Hospital:

George was very quiet on the ward.

Sat and stared. No trouble – and Dad

came every moment he could spare.

But I could not spare George, or un-

wind with bare hands the looped wire

wrapped around his neck, or lift his

dead weight: get his blood to throb

under my fingers… Does God hear

screams for help – or bless torn hands?

Later, taking Dad aside… The bowed

heads and the palsied second death

creeping over the one who loved…

For me, this death has lasted forty years. ‘

Bailey’s Collected Haiku, By The Way, is not represented in this collection, but many haiku are still present:

As a coda to his poem, Father, this haiku:

twilight

watching my father dig

one star above his head

And, elsewhere, his moulting cat is celebrated in Purple Lips:

I rise to meet her:

almost gone within dark clouds

the scarlet sunset.

Coal black the piled mat

of hair, here in my hand, and

there, padding my way.

The purple lips

of my black-haired cat suck gently

on a little mouse.

In the lengthy ‘Miss Stickney’s Poem’, Bailey is inspired by his interest in astronomy and space exploration:

I don’t recall the launch:

only the bruised orange ball hanging in the window,

and I, floating around, not gravitating to any place

in this nice safe room.

The Ai nurse had pulsed another dose —

of drugs, smells, and a Corelli concerto I’ve always loved;

and yet — I hum Singin’ in the Rain: (thump thump ) —

I must sing in the rain…

Patrick B. Osada has recently retired after ten years on the Management Team of South Poetry Magazine and as the magazine’s Reviews Editor. His first collection, Close to the Edge was published in 1996 and won the prestigious Rosemary Arthur Award. He has now published eight further collections including, most recently, The Warfield Poems which was launched in 2024. For more information and a selection of his poetry, visit : www.poetry-patrickosada.co.uk

*****

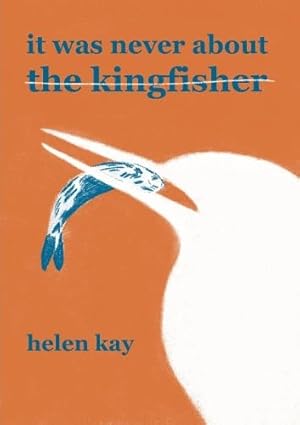

It was never about the kingfisher by Helen Kay. £9.95. Dithering Chaps. ISBN: 978-0957453876. Reviewed by Maggie Mackay

Shortlisted for The Rubery Book Awards Prize, 2025 , Helen Kay’s collection it was never about the kingfisher reveals a graphic landscape filled with tense experiences of family life, the pain of loss, the passage of time, and finally, some growing sense of healing. Cementing the work together is the sunshine line ‘the thrill is that new things still happen’ from the title poem. There’s a powerful sense of figures under duress and in recovery. The piercing language pulls no punches.

The first section is a hard, demanding read. Visceral and, at times, thick with squeamishly effective images expressed through a cinematic lens. Verbs are strong, punchy and sensitive. The poet interrogates the dark, seeking light.

‘Nimby and the Supermoon, 2018’ sets the tone. It’s an angry poem. The narrator struggles with change, new intrusive housing cramping their space and causing self harm. A litany of visceral verbs assault the reader: ‘curtains slice,’ ‘the heart howls,’ the stunning Wildflower Estate / chews up trees and newts / smirks at her terrace.’ It’s a crie de coeur for the loss of green space.

I walk my dog daily through a graveyard so’ Cemetery Dog Walk’ resonates with me. Newly dug graves flaunt gaudy anniversary balloons : ‘icing pink 40’. The narrator finds the ‘grassy graves’ preferrable, the ones with:

‘names eroded / that define death / as green, gentle, anonymous.’

The brash collides with the subtle, the traditional with the contemporary which intentionally upsets the reader’s senses.

The poem ‘After the election :1 Shellfish’ suggests marital conflict over the choice of oysters and their purpose. The oyster mirrors the couple’s intransigence : ‘clenches’ to stay closed just as the vegetarian wife ‘googles oyster sentience.’ It seems there’s hope a pearl might be found, but to no avail. Only grit. A wasted relationship.

The frustration persists.

‘Stomach’ reminds me that my own mother never served up tripe because she had loathed it as a child. For the narrator it too is an unpleasant memory. Kay mixes beautiful and unsavoury images: ‘coral reef of uncooked tripe / chokes in vinegar on her plate.’ The poem’s sensory nature flooded me with cigarette smoke, the intimacy of the cow’s body ‘its cratered skin.’ Another offence against a sentient being. It takes years to dismiss this ‘child self, this ‘it,’ indelible and inedible, a persistent ghostly memory. Parental power is not so easily shaken off.

In ‘Scrabble’ the father appears again, sharing a evening of Scrabble with his offspring, a pastime I took part in with my own elderly mother. But here the mother is ‘out cold upstairs ‘ for some reason unwilling or unable to communicate with family. It’s a relentlessly depressingly screenshot of loneliness set in the era of Milk Tray and Silk Cut: ‘jumbled-up bag / of letters we could never put into words.’

Kay uses specifics to great effect in this set of poems, for example, Carlsberg cans, Tupperware tubs, Horlicks, IKEA, Snow Patrol, Black Sabbath, Battenberg, Quavers, The Daily Mail. The collection is rooted in time and place. She quotes Caliban from The Tempest and Balas on Morpheus and refers to Hildegard von Bingen to great effect. The mundane and everyday similes and metaphors sparkle and lift the common place throughout.

The second section adopts a brighter tone.’ Love Poem’ centres on the sighting of a sparrowhawk, of its hunting of a blackbird : ‘longbow-body in flight, sickle claws, / candle flame beak, a song snuffed out, / a scribble of feathers on grass and blood.’ The figure is anonymous and distant, only a rare phone call.

‘I am sailing’ explores regret after the mother has gone and in hindsight appreciated. The narrator recalls an aspect of their relationship when she was eleven and having her ‘coarse blonde curls’ folded into a ‘tether’ . Direct, like so many of the pieces in the collection, it’s packed with detail: complimented as the child is by her art teacher and the local newspaper, she is brought to heel: ‘ the plait is pulled and pulled’. She mustn’t get above herself.

A sumo blanket offers comfort to a struggling narrator in ‘After the Election 2 : Nimby revival’ who adopts the persona of a wombat: ‘ Her legs uncurl, stretch across the mattress / and callused hands begin to dig a path.’

Danger lingers in ‘With my mother in the garden’. There’s a pervasive underlying threat beneath the allure of the scent of pears, the ‘wide-hipped fruits’, the ‘golden’ of today. The mother: ‘scrubbed the day clean with scourers and Vim’ before there’s a chance to enjoy nature. The wasps are: ‘harmful – voodoo stingers’. The poem ends on the image of mother and child sketching bears, menacing creatures, far from the benign presence of the child’s teddy bear in the first stanza.

A quotation from Walt Whitman leads us into ‘Words my brother left me,’ four sequenced poems about the loss of a family member. The narrator deftly connects their surreal experience at the dentist with that of the cancer patient whose ‘chemo has made you gecko.’ Grief spills out over the wake table, followed by a moment on a named lakeside bench: ‘Loss fixes you to me like a plaque / defined and secure at least.’ The widow sows the deceased’s tomato seeds but the narrator : I wouldn’t mind a lack of ripe tomatoes. Their absence, / red and round beneath the leaves, seems fitting.

Finally ‘A Song of the Sequoia on ness Island’, a favourite of mine. A beautiful spiritual poem , a song of praise for ageing. The voice of an older woman affirms her right ‘to call myself a map of beautiful / wrinkled places, intricate and unafraid’ ‘The GP is cured by Waves at Godfrey lighthouse’’ is joyous. The ‘colours of a Cornish sea@ are celebrated:

In the end

what mattered was us, standing there,

healing ourselves in the break

letting our hearts surf

the space between the surge

and the Ice Age stone below.

‘It Was Never About the Kingfisher’ asserts the complete joy in life, sought over a lifetime as a bird watcher towards a sighting of this bird :‘breath-stealing streak’ that wand beak / and shamanic eye have lived inside me.’ The childhood thrill of a ‘Roses chocolate caramel / being tossed to me at Xmas’. The ultimate pleasure.

A book which energises like ‘green healing’ with the compulsion of a river in full flow.

Maggie Mackay’s poem ‘How to Distil a Guid Scotch Malt’ is in the Poetry Archive’s WordView 2020 permanent collection. Including a wide range of work in print and online magazines and anthologies, her second collection ‘The Babel of Human Travel’ (Impspired.com ) was published in 2022. She has reviewed poetry collections and pamphlets at https://thefridaypoem.com, https://sphinxreview.co.uk, and Reviews | The High Window. She is the besotted companion of beautiful Hattie the Greyt.

*****

the elimination game by Mary Mulholland. £10.99. Broken Sleep Books. ISBN 9781917617215. Reviewed by Sue Wallace-Shaddad

This thoughtful pamphlet about ageing from an older woman’s perspective is written with humour and a hint of rebelliousness at the inevitable. The cover, featuring art work by Okalinichenko, portrays the passion and fire of the tango and seems to hark back to youth. Mulholland captures the sense of time passing in ‘Why I’m Signing Up for Psycho-tango’ with the phrase ‘if i had the wisdom of trees i’d see sixty as young’.

In the first poem ‘Growing a Face’, the physical decline of the elderly is suggested by ‘skin falling in folds as they spoke’. The poet fears older people (‘my people’) are judged as:

a shuffle of wandering fog people

who got it wrong. Wrong our values,

our driving and childrearing, […]

in ‘My People were Chieftains’. She ends the poem by saying ‘skin loose on our bones is our preparation’ and with the warning: ‘one day this will be you’. ‘Hell Hole (Kollhellaren)’ compares the earth’s crust to skin ‘plastic to time and change’ in a powerful poem where the future is ‘a dark cave’ and the narrator is one of the ‘red-oxide figures / running on walls.’

Ageing, however, is also treated with wry humour in ‘Grandmother’s Footsteps’ where poets are seen as ‘urn-waiting crones’ receiving advice from ‘James from the Arts Council’. The narrator would like to apply for a grant, ‘stuff it in an urn and post it to Patricia’. Humour also features in the prose poem ‘the elimination game’ where the narrator rails against assumptions she might be a ‘batty old trout’ by boasting of recent adventures – trekking and rollerblading for example.

Generations are a subtheme in the pamphlet. The lovely poem ‘Croissants’ describes time spent with the poet’s daughter and grandchildren under a lime tree, musing: ‘Perhaps even children find it hard to be children’. In ‘Fallen Tree’ the narrator tells grandchildren about their father, grandparents and great-grandparents as they all pretend the fallen oak is a plane. The poem ends with the poignant words ‘[…] fallen / trees sometimes right themselves.’ Concern about the safety of grandchildren runs through the beautifully observed poem ‘The Grandmothers’ and ‘the colour of wrongdoings’ haunts ‘The Regretting Room’ following a mother’s death.

Mulholland writes descriptions with a lightness of touch. ‘Reading the Silence’ starts ‘The sound of the sea is his breathing’. The scene is of a couple sitting together, the man reading, the woman knitting. Quatrains create a slow steady pace and the poem ends with simple words that say volumes about the relationship:

[…] She glances. He raises an eyebrow,

she half-smiles.

I was struck by the poet’s rich use of language and cultural allusion. She includes words such as ‘noachian’, ‘hirsute’, ‘postiche’, ‘anechoic’ and ‘dace’. Lowry, De Ribera, the Sphinx and Hatshepsut feature in the poem ‘Beard’. Luke Howard is mentioned as a correspondent on cloud formation with ‘Goethe, Constable, Ruskin’ in the poem ‘Pietà’.

The final poem ‘Stilling Time’ is a wonderful poem to end with – it once again shows the breadth of Mulholland’s cultural range taking us from ‘eleanor of aquitaine’ to ‘a black stone ninety million years old’. She surmises that touching the latter will make her ‘feel young’. The poem holds stillness in its couplets and in its images of elk at dawn, peace and shadow.

This is a pamphlet to savour, reflecting Mulholland’s experience of life and insight gained. As she writes in ‘Woodstock’, a poem recalling youth, she – and her poems – ‘contain multitudes’.

Sue Wallace-Shaddad has three poetry pamphlets:‘Once There Was Colour’ (Palewell Press 2024)Sleeping Under Clouds (Clayhanger Press 2023) and A City Waking Up (Dempsey and Windle, 2020). London Grip, Artemis, The High Window, Fenland Poetry Journal, Ink Sweat & Tears, Acumen, Orbis and Finished Creatures among others have published her poems. She is a trustee of Suffolk Poetry Society, writes reviews and runs workshops. She was digital writer-in-residence for The Charles Causley Trust’s The Maker 2022-2025 https://suewallaceshaddad.wordpress.com

*****

Foreign Forays by Antony Johae. Mica Press. £9.00. ISBN: 9781869848392. Reviewed by Sally Festing

The reader has no doubt about the theme of Foreign Forays. Title, dedication and introduction all clarify Johae’s lifelong aspiration to travel by bike, train or air.

Here in the deep-blue-dusk

my mind’s full of flights –

from ‘Staring through My Window in Winter’

Foreign explorations begin in Belgium where a medical therapist salutes his need to forge ahead. In France, the poet pays tribute to its boulangeries as well as its architecture, weaving poems from chance encounters before moving to Prague in an old VW van. Forward into Poland where, for anyone born during a major war, the country’s horrific past inevitably invites political asides.

Love and Lebanon first appear in proximity in poem 14 (page 17) of 25. This is followed by marriage and family with a Lebanese lover ‘Maqam in the Park of Baths’, poem 18 (page 22).

…Had there been words

they would have heard of love – spotless,

soaring sunward; unrequited, dragged to earth.

Bio notes give ‘a comparative study of Dostoevsky and Kafka’ as the subject of Johae’s Ph.D thesis. This background to his travels intrigued me. His journeys, some ekphrastic, others decidedly musical, make a round tour. Henceforth he plans to split time between Colchester, UK and the Mediterranean. ‘Wanderlust’ might have been an even more adroit title.

Sally Festing’s seventh poetry collection, Meeting Places (Mica Press) was launched this year, wrapping up love, blood ties, art, and aging in a spikey bundle. Her poems have won prizes and featured in 42 different magazines. Ten years of journalism followed by Penguin biographies of Gertrude Jekyll, Barbara Hepworth and other non-fiction books preceded poetry that’s now concentrated in North Norfolk. (https://www.sallyfesting.info).

*****