*****

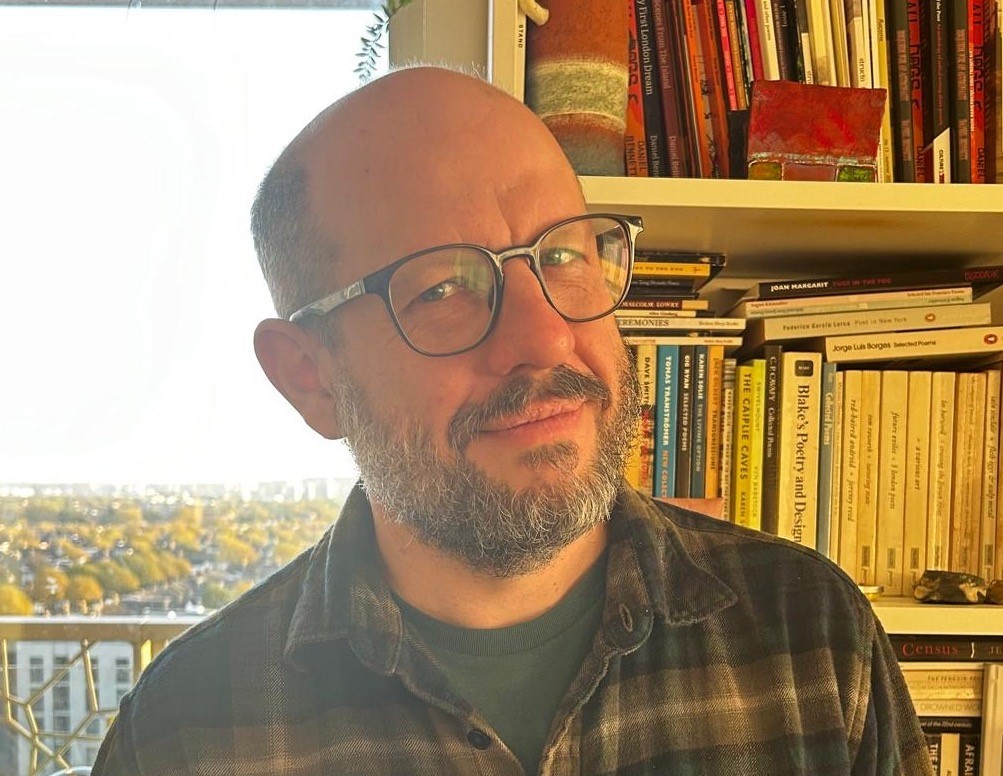

Daniel Bennett was born in Shropshire and lives in London, where he teaches for the Open University. His poem ‘Clickbait’ was commended in the 2020 National Poetry Competition and his work has been published in a variety of places, including: Wild Court, Stand, The Manchester Review, and Structo. His first collection West South North, North South East was published in 2019 by the High Window Press. You see more about his writing, both poetry and fiction, on his website: https://absenceclub.com.

*****

NB: Copies of Daniel’s debut collection are available here:

*****

Introduction

I grew up in a small hamlet in the Shropshire countryside, on the face of it a perfect upbringing for a poet. And, while this landscape has never been far from my writing, and I never seem to escape the topography of this isolated place, I’ve always shied away from nature writing, in part because I don’t think I do it very well, but mainly because I’ve ended up following wilder paths, however much the straight track might have eased my way.

Besides, even in childhood, the natural world was never enough for me. Maybe it was the triumph of electronic media, the doomy eighties news stories of impending nuclear war, or all those odd invasion fantasies proliferating in television: I became more concerned with what the landscape could become more than I did investing real time in what it was. A friend and I once conceived of an ideal community, a way of updating our humdrum neighbourhood. We took the project quite seriously, designing maps and drawing up plans for a future beyond automobiles and conventional modes of transport. What we were building, I think, was a perfect city, even before I ever visited a city, ever really thought about what it might be like to live in one. Later, I moved to London, a collection of villages and hamlets that has fused at the edges, blurring like pin mould, and I found my home among the relative distinctions of Highbury, Finsbury Park, Acton, Brixton, Streatham, or East Ham.

Back when I had definite ambition, I gave up poetry for a time, and turned to fiction, writing a novel which ended up being based in the landscape of my birth. During a testing period of my life, my fiction began to fray at the edges. I turned to poetry again to make something out of those years, not so much to confess (I don’t have much to confess) but to record. I’ve been lucky enough to spend the last few years travelling abroad, and the method of the tourist— making notes, attuning myself to a certain scene or space before moving on— has become increasingly attractive. Whenever I think of myself as a poet at all, beyond the other roles I have as a husband, father, son, colleague, painter, tutor, writer, it’s to picture someone at the edges of a city, recording the exchanges and memories: someone perpetually longing for a place, beyond the place he seem to be occupying, whether for the people who inhabit those places, or out of some barely-understood wanderlust. [DB]

*****

Daniel Bennett: Seven Poems

SPITALFIELDS

Count the ghosts— they’ve gone.

The louche antiques dealer

of Vesalius etchings and tribal masks.

The tender spiv selling waistcoats,

Hawaiian shirts, a broken Leica.

The women from the commune,

offering the sour steam of lamb.

Why fall in love with places, times?

Why expect them to always remain

steady and tolerant as parents

as you roll back in, after years away,

to tell stories of divorce and yoga,

your shoes all over the sofa cushions.

You’ll know the cry when you hear it.

It echoes inside a sherry cask,

wobbling against sticky lees,

becoming scratchy, interminable:

it’s the sob of lazy heartbreak.

The whole world passes through

a flea market, eking out one last sale

before throwing itself on the junk-heap.

Somewhere, a hospital bed waits,

its springs already shrieking

with the weight you’ll bring.

A line of red earth is buried deep

from the times this city has burned,

and it ghosts your steps as you tread

west south north, north south east.

DRY DOCK

An inlet along that ragged creek.

Hemlock beading in hedges,

cow parsley, elderflower, the lump of summer

thick in our throats; the tones

of water drawn out over mud

where we tried paddling once

when you were very young, and found

an oiled impasto of squelchy green

mixing with rust, petrol, pig iron, steel.

Those areas along the bitten coast

were alighting points

to different levels of nowhere,

gnarly scraps of pooled waste,

a litter of fuel canisters and sordid plastic,

rusted shotgun pellets, fishing tackle.

We came across the dry dock

beyond a place renting stretch limousines,

which said much about someone’s priorities.

The boats lay stacked above us in rows,

emblems of disaster, orderly markers

of a great flood, long since passed.

Sloops and cutters, the pleasure craft

we’d watch making serene chaos

as they slid down our local channel.

On a landing sloped towards the water,

we found a boat pulled up for works

a water line blurred against its blue paint,

a dandelion-yellow cabin, flowers daubed

around the portals, an island even on land

and later I’d feel we’d found our place

in that soupy geography of your childhood,

despite landing here by accident.

And although some nights I still wake

imagining I’ve left you alone

by the edge of those incongruous waters

to make your own way home,

I’d like to place this memory

deep into your mind,

a seed pushed into earth.

THE DIVES

I tripped into a former life

by Seymour Place, Cato Street,

the corner pubs named after trades

I might have taken as my own—

Shepherd, Carpenter, Bricklayer—

although I’d worked in a wine shop

at the time, handling bottles

of Fronsac, Thalbert, Meursault

with a kind of saintly dedication,

back when my cheeks were blue

and my heart held this colour

sealed inside, like blood starved

of its oxygen, like slender ice.

The acid of spoiled ale lingered

in the dark wood, bitter as varnish

brown as malt vinegar, its mystery

returning to me from the years

I would walk past the village local,

too young to step beyond the door,

before the days I came to know

the inches of sadness gathered

in the bases of half pint glasses

of Fosters, Stella, Heineken

discarded by a vacant dartboard,

the longing and hopeless energy

of spectators drowning themselves

in an aquarium of sports television,

the nights I’d appraise the shapes

barmen would pattern into foam:

a clover, a smile, a heart, a crown

commemorating my entrance

to the city, the palms scattered

through the streets I would claim,

and I chased this shadow of myself

back across the days of no promises.

THE LAST WATER

We came to the lake through a wood,

the cold waiting for us in shadows,

like puddles of autumn, the world

already drowned in our longing.

Granite and oolite studded the path,

rough quartz, brazen as sea shells,

although our heathen days

made us resist the lesson of parables,

as we had moved towards stories

of pure invention. Birches grew close

to the water but we dreamed

beyond them. Our lovers gathered

in the tree line, static and implacable.

An ideal of water drew us onwards:

its colours of steel, lead, petroleum

and the light crinkling on waves

is the light running off mountains,

a cold tincture of prehistory.

We looked for shortcuts to the edge

scratching shapes in the dust

to those who will follow this path:

the forms of stick people, and lines

illustrating our rude topography,

the hideouts woven from branches,

we hoped would outlast our passing.

Our children had grown older

and would not let us carry them,

and we had forgotten the last time

they allowed us to carry them.

Instead, we rediscovered play

for ourselves, old as we were, pinched

and asthmatic under the white sun,

leaping from crags in volcanic rock

out in the far depths, as fish

stirred fins through silky mud,

and we lost our senses to the chill.

THE PENGUIN BOOK OF AMERICAN VERSE

I saw a city and walked a town

not knowing I would reach a city

and imagine home. One summer,

I rode shotgun with my father

to the fire station where he paced

the routine of work, as I traced

tumbleweed of western dreams,

library-bound, a satchel stuffed

with paperbacks, to the stacks

which offered portals to beyond.

A town became a desert, a road

a road movie, and the fields

of yellow rape I crossed to reach

the boredom of a Saturday job

became a proxy for cinema:

retreats where streams rinsed

through sad backwoods of sticks

and brambles, hard orange earth.

My father tried to ground me

but I floated through elsewhere,

adopting Americana as a system

of making strange, liberating

imagination from the realities

of place. Where does it come from

this longing, like loss? My father

drove fast along the rural roads

always impatient for home and

we felt disaster wait at each corner,

as his radio called out accidents,

houses on fire, a world fit to burn.

90s ROAD MOVIE, POSSIBLY MISREMEMBERED

Black and white, maybe. The chiaroscuro

of noon sun on chain link fences,

a close up of tarmac, kerbsides,

the grungy outskirts of the mute city.

Something bluesy on the soundtrack,

a slide guitar chiming over steaming pipes,

rolling stock, a piebald dog, the credits

a funky scrawl. Here we inhabit

the borderland between cliché

and the reinvention of myth,

between form and its zealous pastiche,

an extended advertisement for an ideal

where narrative shape is offered only

by forward momentum. Story

is landscape and landscape is story.

Landscape is character. Landscape is everything.

Done with the city, the parabolic scuff

of rattlesnakes in white sand leads us

into a desert realm. An eagle circles

in the sky, its wild hover a clatter

of wing feathers. Lens flare. Fata Morgana.

A bird handler waits beyond the rise,

an old man who might be played

by Harry Dean Stanton (if we’re lucky)

who guides us the remaining miles

to a forgotten border town. Here

the pace will pool. Phone lines thrum

with ambient tension. The residents

open up homes, offer minor comedy

of frontier manners, scratchy TV.

The grotesqueries of outsider art,

provide the mise-en-scene: sheep skulls

on staffs, windmills clacking through

the hours, a junkyard patina. The return journey

will always pull at us: like the final call

of lost longing, like my poor naive hope.

THE FOX AT THE DOOR

She said the fox called at her door

every morning that summer

when no one went anywhere

and the city blurred into nature,

a wilderness of grounded flights,

cancelled flyovers. I imagined

that it had never been a fox at all

but an errant father, making peace

through emptied out alleyways

and brutalist shopping precincts,

or a mother escaping remission

inside a grungy coastal town

reaching across back streets

towards a daughter estranged

by train lines and circumstance.

We should beware of such magic.

On moving to the city, I saw foxes

as ragged emblems of a country

upbringing, shabby interlopers,

reckless as empathy. Such myths

end badly: ex-lovers reunite

in tricksy disguises, lost children

return to us mutable and strange.

Or we transform nature into traits

explaining only ourselves, or even

take someone’s life and make

what we want of it. Fox politics,

she called it when the visitor left,

pushed out by a territorial shift.

Only a fox could have returned

to receive the egg from her hand

that final time, closing the ritual

which had occupied her days

and race into a blank morning,

through a chamber of the blown city.