*****

Gillian Allnutt: Lode • Peter Robinson: Return to Sendai, New & Selected Poems 1973-2024 • Steve Malmude: Red Carpet • Carlie Hoffman: One More World Like This World • Christina Thatcher: Breaking a Mare

*****

Lode by Gillian Allnutt. £12.00. Bloodaxe Books, 2025. ISBN 978-1-78037-745-2. Reviewed by D.V. Prince

The word ‘lode’ has slipped out of everyday use so Gillian Allnutt’s brief list of definitions at the start of this collection provides a useful introduction. Never used as a title, and not appearing in a poem until the penultimate poem (‘for only then can’) ‘lode’ can mean a journey (or road), or guidance, or a fen drain. All are applicable, at varying points, to the poems in this collection. The title’s modesty echoes that of Allnutt’s previous collection, Wake, and reflects her quality of intense concentration on small differences, whether visual or aural. This is her 10th collection, showing work that becomes ever more closely focussed, not only on her immediate surroundings but on connections — both material and spiritual — to a larger world. She was awarded the Queen’s Medal for Poetry in 2016 but is still comparatively little known compared with younger, more publicity-seeking poets.

That may make her work sound complex but she balances this with notes that are accessible and warm, filling out family background, sources of quotations, even geographical references. Lode is divided into three sections, ‘Postwar,’ ‘Lockdown’ and ‘Earth-hoard’ but there are verbal echoes between the sections, expanding the themes, and holding the poems together as an entity. Because this aural echoing is a key part of her writing I’m going to criss-cross the collection rather than treat the poems as a linear accumulation. So, to begin at the end: on the final page, and coming after the Notes (the expected conclusion of any collection) is a three-line poem, ‘Roughage’, close to a haiku in spirit, with the final line: ‘World without edge.’ This is her vision of the world, a place of echo and unity and connection. The words ‘world without end’, which close so many Collects in the Book of Common Prayer, are echoed here. Not every reader will recognise this but that doesn’t matter: it’s a powerful enough ending. But for those who hear the echo there is an extra layer of meaning.

The poems grouped in ‘Postwar’ are, largely, connected to family memories, including family members Allnutt only knew through others. ‘Poem for John Clinging’ opens:

Of you, John, there was nothing to go on —

nothing but your smithereen of skin and bone and plane.

You were one of the quick and the dead

and far too many of them to crowd into the dining room.

He is one whom Allnutt has taken ‘into my own heart’s pondering’, her mother’s brother kept alive by being remembered. This is one of the many poems where Allnutt chooses to give each line extra space, suggesting the weighted silence required by the act of memorialising. Her quotation from the Book of Common Prayer continues the idea of the ‘smithereen’, all that was left of his earthly body. Time spent with this line reveals Allnutt’s precision and musicality: the alliteration and vowel-play in ‘skin and bone and plane’. It may seem strange that I’m homing in on tiny aural features so early in this review but reading Allnutt requires this level of attention throughout.

Take, for example, ‘Azuma Meditation’, one of the Lockdown poems, describing the first online meeting of a meditation group that had previously met in an upstairs room near Durham railway station. Now, unable to meet in person, they bring ‘… the severed silence of the heart’ from their scattered villages. It opens

Only connect, communicate

courtesy of Zoom —

just as we are, we say, as if we were at home.

Zoom, the online meeting place most of us encountered only in 2020 (although it was originally developed in 2013) catches a rhyme from the title but this puzzle is only resolved in the final tercet, supported by Allnutt’s helpful Notes.

What did we gain or lose when we listened instead

to the breathing of the trains — azuma, azuma —

paused on the viaduct?

‘Azuma’ is a type of train used by LNER. There’s a playfulness in the rhyme, underlined by the hint given in ‘connect’ in the opening line. How many levels of connection are working together here? That’s a key question raised in Allnutt’s poems and it extends beyond the poems themselves, into the reader’s perception of their own connectedness to their surroundings, both material and spiritual. Lockdown, for so many the opposite of physical connection, is a preoccupation, and her poems take us back into where we were after March 2020. ‘The walk (allowed)’ reminds us, with even the parentheses in the title recalling our separate enclosures, what limits were placed on us:

First lambs in the field on the far side of the hill.

Here I am stilled, no longer held

by the host and hostelry of the world

too much with me.

Animal life continues, valued for its constancy, while Allnutt is linked to it by the rhyme (‘hill’, ‘stilled’), the alliteration (‘held’, ’host’, ‘hostelry’), and an allusion to Wordsworth that touches on what we used to take for granted, the world’s busyness and rattle. ‘It’s tea-time / in the small eternity of lockdown’ she writes (in ‘My Garden in Esh Winning’) and, with a chilling acknowledgement of the daily news, ‘Truth — as we, foolish, applaud with saucepan and wooden spoon — / Is the ambulance standing alone in the back lane.’ (from ‘To be honest’). She writes of face masks, clouded glasses, ‘the wait and see of every morning’ (from ‘Lockdown’) and the clock she left behind in York University, a gift from one of her students who had returned to Singapore. Allnutt can see the stretch of the world in small, personal matters.

I wonder if there is any other poet who could close a poem about making crab apple jelly (dedicated to her niece, Clara) with a quotation from Julian of Norwich? An account of the process, from the ‘two tied-together bamboo poles’ laid across two chairs to the jelly bag’s corners tied for security, move from the detail into the higher reaches of the spirit.

and all shall be well

and the moon and the heron, all manner of thing, shall be well.

Would any other poet evoke the medieval world through a singular ‘thing’ instead of our modern plural?

In recent collections Allnutt’s poetry has settled into a close and quiet attentiveness to the minutiae of life, and how this informs our relationship with things of the spirit. She is writing of herself, of her own observed experience, but this expands to become universal. This is in sharp contrast to much of what is published in the third decade of the twenty-first century and we should treasure her work, reading it slowly and giving it the contemplation it deserves.

D.A.Prince lives in Leicestershire and London. Her second full-length collection, Common Ground (HappenStance, 2014) won the East Midlands Book Award 2015. Her third collection, The Bigger Picture, also from HappenStance, was published in 2022. New Walk Editions published her pamphlet, Continuous Present, in June 2025.

*****

Return to Sendai, New & Selected Poems 1973-2024 by Peter Robinson. $22.95. MadHat Press, Cheshire, MA. ISBN: 978-1-952335-92-1. Reviewed by Kathleen McPhilemy

Peter Robinson is a much-esteemed poet with admirers as far apart as Marjorie Perloff and the late Roy Fisher. In addition, he is a respected translator and an indefatigable promoter of poetry through his criticism, editorship of different magazines and most recently, his work as Professor of Creative Writing, which is one of his roles at the University of Reading. Roy Fisher, in the foreword to this volume, which Robinson must endorse as he has chosen to reprint it from a piece written in 2004, comments on the autobiographical nature of Robinson’s work and of the closeness of the poetic ‘I’ to Robinson’s empirical ‘I’. Fisher also analyses the oblique nature of this autobiographical approach. ‘It’s as if he carries a listening device, alert for the moments when the tectonic plates of mental experience slide quietly one beneath another to create paradoxes and complexities that call for poems to be made’. (p.xiv)

Robinson makes poems about the places where he has been, about world events and about family and friends but it can be difficult for the reader-outsider to make sense of the poem as a work of art when so often it is attached to private reference. As readers, sharing an existence in the universe of ‘things as they are’, the empirical, historical world, we may find dates and contexts helpful in building our sense of a poem. To make matters more difficult, Robinson has chosen to group the poems thematically rather than chronologically, a decision perhaps prompted by Roy Fisher: ‘…I’m disinclined to recommend a simple chronological reading of these poems, or any attempt to trace lines of development … Robinson’s work simply blocks that option. Individual poems have individual lives, individual musical qualities … each work can be seen as something added to the world rather than a mere notebook commentary upon it.’ (p.xvi-xvii). Certainly, there are some poems which allow the reader to appreciate a detached ‘something added to the world’. ‘Equivocal Isle’ (p.70) is a beautiful poem where the experience becomes metaphor without any sense of stress or need for further contextualisation as a boat journey towards ‘an island bearded with pine tufts / [which] echoes the dark in its design’ becomes an expression of feelings about death. Here, as elsewhere, it is the experience of the poet in the landscape or the event not the external scene or incidents which become the matter of the poem.

The life from which Robinson’s poems have been made has not been uneventful or devoid of trauma; it has included seeing a female companion raped at gunpoint in Italy and surviving major surgery for a benign brain tumour as well as living and working in Japan, Italy and England. Perhaps because of his ‘three-cornered’ life, in Japan, Italy and the UK, many of his poems seem to be concerned with travelling, on planes, boats and trains. The cover reflects this sense of constant motion and reflects the first poem in ‘Suite Americana’: ‘NO STANDING ANYTIME the sign says, / and so we keep on walking, walking, /walking in New York … // but where we’re going and what we are doing /I couldn’t rightly tell you’ (p.25). This is a poem of deep pessimism, preceding Trump’s re-election, where the actuality of being in New York, I think with his wife, is overlaid by his and their feelings about the election. The different elements of the experience are brought together to create a poem, which because of its loose ends and information not given, forces the reader to their own interpretation:

Still my take on it is not the world –

but sensing that, you can glimpse unfold

a future’s anxious days, its fates,

though no longer setting the world to rights

with your Pindaric flights –

who’ve still not had enough of Frank O’Hara,

Elizabeth Bishop and Langston Hughes

or the truth of things, things as they are,

come Fall’s deep blankness through turned leaves

those days before that news. (p.31)

In some ways, this is typical of Robinson: who is ‘you’ and what were ‘your Pindaric flights’; who is so enthusiastic about these iconic American poets (Wallace Stevens is also present, ‘things as they are’) and how should we take ‘Fall’s deep blankness’?

This is a poet who criss-crosses the mutable boundaries of ‘things as they are’ and the coterminous continuing world of art, poetry and fiction, and it is not always easy for the reader to keep up. He has no fixed point, but is always going somewhere else, although there are momentary epiphanies, as in the runway poem, ‘Enigmas of Departure’, (p.14) ‘It was while I walked out to the plane … came a sense / of release in roaring silence…’ Although in some ways a very English poet, he is the type of an Englishman abroad, cultured, well-read, European and international. There are a few poems about England, one about his grandfather, another about his mother, almost book-ending this volume. ‘Crosscountry’, again on a train, takes us across a post-colonial, post-Brexit England ‘on that interminable journey back home’:

our train, suffused by the sunset glow

crawls on its fixed timetable,

and still nobody’s able

in the lingering twilight’s extended shadow

to tell how far we’re to stay or go.

The poem opens with a pun ‘Never a day without a line’, a quotation from Pliny, which reminds us of the mission to make poems out of experience. ‘Unheimlich Leben’ (p.178) suggests an uneasiness about being in the UK, while “Loud Weather’, (p.175) may suggest a longing for the Europe which Brexit has detached Britain from, ‘I need you in all honesty. / It’s as if I could still feel the cut cord bleed.’

When not in transit, the poet is often to be found in a gallery. Like John Ashbery, Robinson has a strong interest in the visual arts, and, as with Ashbery, it is the putting together or collaging of experiences, including experiences of art and literature, which become the poem. Perhaps something of his stance can be understood from the poem, ‘At the Institute – after Charles Sheeler’ (p.9), apparently written at the time of the Iraq war:

Mr. President himself was defending his own

legacy, his bloody adventure –

was “staying the course”, he would “get the job done,”

a refurbishment worker’s too-loud radio

come thoughtlessly from an adjacent room…

and just so’s I wouldn’t forget

there The Artist Looks at Nature

was a painter in his studio

touching the hard edge where life and art met.

The painting in question shows the artist looking at a scene of nature but painting an old iron stove which was the subject of photographs he had taken in the past. The gallery comment on the picture is ‘Here, Sheeler engaged in reconstructing his own artistic past—looking back at his work across media and reconfiguring it into something new and surreal in the present.’ https://www.artic.edu/artworks/49714/the-artist-looks-at-nature

Robinson has said that he makes poems for readers to construct their own meaning, which is fair enough, but becomes a problem when too many elements are private or not widely shared. Many of these poems have dedicatees or epigrams which will not be recognised by the outsider. Add to this, Robinson’s fondness for puns, from the title which is a take on Presley’s ‘Return to Sender’, apparently a karaoke favourite, to the almost painful ‘rush home/ Rusholme’ in the opening poem; his often very complicated syntax which can make it very difficult to work out who or what is the subject of a sentence; his use of quotation and intertextuality which pops up all over the place; his cavalier use of rhyme and form; and his sudden, surprising changes of tone and register. In ‘Above the Sea’ (p.164), which I read as a love poem, he asks: ‘how give / sensations a plot sounding true to one another, / and how plait the threads together / or leave them dangling…’ Robinson leaves too many threads dangling for his poetry to be a comfortable read, but it has love and passion and is a convincing argument for the life of a poet as a life lived in the world.

Kathleen McPhilemy grew up in Belfast but now lives in Oxford. She has published four collections of poetry, the most recent being Back Country, Littoral Press, 2022. She also hosts a poetry podcast magazine, Poetry Worth Hearing https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/kathleen-mcphilemy.

*****

Red Carpet by Steve Malmude ed. Miles Champion. £14.99. Carcanet. ISBN: 9781800174979. Reviewed by Ian Pople

Steve Malmude is cited as a ‘second-generation poet of the New York School,’ an epithet which tends bestowed on quite a lot of poets. In fact, the New York School label doesn’t always fit Malmude who is sometimes a formalist with a fondness for rhyme, and whose early influence is Robert Lowell. However, two cover blurbs by Ron Silliman and Clark Coolidge do place Malmude in the New York ‘area.’ Silliman, in particular, comments that with James Schuyler, Malmude was one of ‘only two of that school’s practitioners to develop ‘an identifiable and unique sense of line.’ Like Schuyler, Malmude has a fondness for the very thin poem where a line contains very short phrases of one, two or three words, and which may run down a single page. One such is ‘Hoboken,’ which I quote in full.

If Hoboken

had a ferry

I’d sink

roots here

the father

of athletics

is a faceted

figure

loosely

connected

to the Kool

Jazz festival

the library

is open

nonjudgemental

free

in the carrel

of the library

I see

Carol

her famous

yawn

is territorial

display

It is possible to see, I suspect, what Silliman means by Malmude’s control of the line; although that control is firstly manifest in the control of the stanza. In ‘Hoboken,’ Malmude’s stanzas contain what we might loosely call a ‘thought unit,’ manifest in a complete clauses. And we might also wonder whether the poem started its life in prose clauses that Malmude subsequently cut up into lines and stanzas.

The contents and juxtapositions between the stanzas could loosely fit our rather received idea of what a ‘New York School Poem’ might look like. There is a relaxed, conversational movement between those ideas. ‘Hoboken’ has a rather briefer version of the free-flowing associations that an O’Hara or a Schuyler might conjure out of a relationship with Hoboken. And Malmude, like those two writers, places the noticing self at the forefront of that relationship with Hoboken. The poem starts by establishing a relationship with the city, and it’s a relationship which, it is implied, is instrumental. The narrator of the poem would need the ferry for work, perhaps. Then, the poem moves rather tangentially to whoever ‘the father / of athletics’ might be and that slightly odd movement is emphasized by not only his being ‘faceted,’ but also with his being ‘loosely / connected / to the Kool / Jazz Festival.’ Then the writer and the reader move on to the library with its named inhabitant, Carol, whose name just happens to rhyme with ‘carrel.’ The poem runs through a series of judgements: on the city, the father of athletics, the library and Carol. This is not quite the sense of appropriation which tends to be castigated these days but comes perilously close particularly in its view of Carol.

We are, however, invited, ourselves, to judge the judgements. The New York School was nothing if not democratic in its sentiments, and this was true even of the writings of John Ashbery at his most vatic. Thus, the ‘I’ that populates ‘Hoboken,’ often the first person of the authorizing consciousness of the poem is open for judgement. Elsewhere, though, the ‘I’ can be a kind of surreal placeholder, as in the poem, ‘I got to know.’

Spring rain

washes the arrow

out of the head

of the snowman

it is the sign

that our case

has been

diagnosed

one has

another day

to acquiesce

I got to know

my colognes

this morning

and they

got to know me

Because the tone of this poems is essentially quite light, the invitation here is to assume that the ‘I’ here is Steve Malmude, the authorizing consciousness I mentioned above. That sense of the authorizing consciousness might be why the back cover blurb suggests that Malmude’s poems are ‘hieratic, almost ideogrammatic poems made slowly and carefully.’ The four brief, almost curt, verses of ‘I got to know,’ force the reader to slow down. And the juxtapositions of images and ideas also force the reader to take stock as they move from image to image. In this poem, the reader, too, ‘gets to know.’ What exactly the arrow is doing in the head of the snowman, we can but speculate and there is an interesting juxtaposition between the words ‘arrow’ and ‘head’ that Malmude’s poetics suggest might be deliberate. This deliberate quality is also contained in the ‘it is the sign’ that follows. The arrow is a sign for those whose case has been diagnosed though, again, the reader might not be any the wiser. The diagnosis, it appears, allows the narrator to get to know their colognes. So the poem has its own trajectory, quietly but firmly held.

Red Carpet is a quietly fascinating book. In that rather cliched phrase, it is one to return to. There is a slight sameness in the tone of the poems, but to put the book down and then come back to it, is to encounter a poet with an endlessly interesting perspective on the world, surreal but never jarringly so, and always in dialogue with a warm and approachable reality.

*****

Carlie Hoffman One More World Like This World Four Way Books, £13.40, 9781961897281. Reviewed by Ian Pople

Carlie Hoffman’s previous book When There Was Light introduced this reader to a poet who could move with considerable grace between the dark and the light. That moving between light and dark was not only managed with sustained grace but also with a canny, often surprising use of metaphor. Thus, Hoffman’s language was loamy and rich. That sense of rich depth permeates Hoffman’s new book One More World Like This World. In part, this is because of Hoffman’s use of the Eurydice and Persephone myths and the depths those myths explore. In addition, Hoffman’s new book explores, the idea of being and what it means to be present within the swirling world we increasingly inhabit. Perhaps, being present in the current maelstrom in which we live is part of what the title of the book alludes to. The phrase ‘one more world like this world,’ contains not only a sense of deracination, which Hoffman, as a writer who has more than once alluded to her Jewishness, would more than understand. That phrase may also offer a kind of ambivalent, somewhat weary, hope; that there may be another way which is ‘like’ but is also a different ‘one more.’

One More World Like This World is a book that exists inside those tensions, light and dark, this world and another world, where Hoffman’s rich skill is to create poetry that animates the tension and make it palpable to the reader. Part of that tension might arise out of her clear sense of the clash of identities, but her skill is to use that clash in the contemporary world and run with it. Thus, Hoffman’s poems never lapse into any easy sense of what has come to be known as the identitarian. Identitarian poetry can often seem too easily to wear its identity on its sleeve, which Hoffman doesn’t do. And this is because Hoffman’s world is simply too complex, too multifaceted, too aware of its situation to allow itself to totalize.

Some of that complexity is shown in the sheer range of authors, Hoffman references. But One More World Like This World is not actually a trip round other authors. What those authors do for Hoffman is allow her to expand through the real world. ‘Borges Sells Me the Apple, Sells Me the World,’ begins, ‘In the blizzard / of my life // nothing moved me, my voice / an empty basin, stone // taking on the mouth’s shape. / If I heard music // it was a sound from below, vibration / thickening from under the earth.’ If Eve is the narrator here, this is an Eve susceptible to the calling of the snake because the offering of the snake might appeal to a need in this Eve to move beyond the condition she finds herself in. This is an Eve without a voice and where her engagement with that world is, on the one hand, life as a blizzard and, on the other hand, a kind of earthquake; neither of which offer stability. And in the midst of that, the apple is a disappointment. And yet it is the promise of the apple which sustains. The poem finishes, ‘Imagine / believing what you know so forcefully // you will live this blizzard / all your life for this apple.’ And if the reference in the title to Borges feels enigmatic, then it might be a reference to Borges’ poem, ‘Happiness’, which begins, ‘Whoever embraces a woman is Adam. The woman is Eve. / Everything happens for the first time.’

The heteronormativity of these lines might cause us to flinch a little these days. And yet Borges reaches beyond the social to the archetype. If Hoffman is responding to that archetype, she is suggesting, perhaps, that it is in reaching into the emotional experience. It is the core of the emotion that offers a pure sense of being. And yet, Hoffman is quick to acknowledge that it is the imperative of ‘Imagine,’ that prefaces all this. That newness of imagination alludes, perhaps, to Borges’ declaration that ‘Everything happens for the first time,’ although Borges’ emphasis is on the ‘happens’, the reifying of that imagination.

This is ‘Moses in Brooklyn,’

Bleating, scattered suns of geese

overhead, a flame alphabet:

what is unwritten, hardened

into language, lays bare

a sky. Then the omen

in C-town on Graham Avenue, lambs

to the left, animal among

the animals. Half-broken figure

bent under the smoke-

feathered sky, day

and night – I

am composing you.

In notes appended to the book, Hoffmann states that the italicized lines here come from a Celan poem. The poem’s title in French is ‘A La Pointe Acérée,’ in reference to which, Hoffman cites the translator, David Young, ‘translates as “with a steel-sharp point” or “in a pointed manner.”’

‘Moses in Brooklyn,’ is a good example of Hoffman’s use of metaphor and her heightened sense of description. Hoffman’s Moses descends from a metaphorical Mount Sinai into Brooklyn under ‘scattered suns of geese.’ We might think that a move from ‘skeins of geese,’ to ‘suns of geese,’ is a slightly self-conscious swerve. But Hoffman has the chutzpah to make that swerve. And what she also does is to start with the bathos of the geese bleating, then move to the images of the sun and the flame alphabet, that alphabet in which the Ten Commandments are written. The imagery then pulls us towards Celan’s declaration. Celan’s statement is clearly ambiguous in a way we might come to expect from Celan. Yet, Hoffman’s placing it where she does moves the imagery and the statement into a juxtaposition which renders them even more heightened, an intensifying that is doubled with the statement that follows the Celan on the same line ‘Then the omen.’ That intensity is then situated in the superb banality of the C-town supermarket on Graham Avenue in Brooklyn, and yet that is where the omen is found. Here, where the Lamb (of God?) is among the aisles on the left, meat among meat. Here, too, Moses is a ‘half-broken figure,’ the one who leads the tribes of Israel to the Promised Land. But this is a Moses who is made and depicted, it seems, by the writer, who may or may not be Hoffman, the authorizing consciousness of the poem. If the Law brought down from Sinai is compromised in ‘Moses in Brooklyn,’ the compromise is not that of the poet, who sees that the words are composed in a flame alphabet, even if the figure that brings them down from the mountain is half-broken.

If One More World Like This World is a darker book than Hoffman’s previous, that is, perhaps, because of this book’s seeming larger reach into what it means to ‘be’ in a world of differences. That ‘being’ in Hoffman’s writing is always on a quest to see not what that being means, as such. It is on a quest to see what that being might involve in all its depth and variousness.

xxx

*****

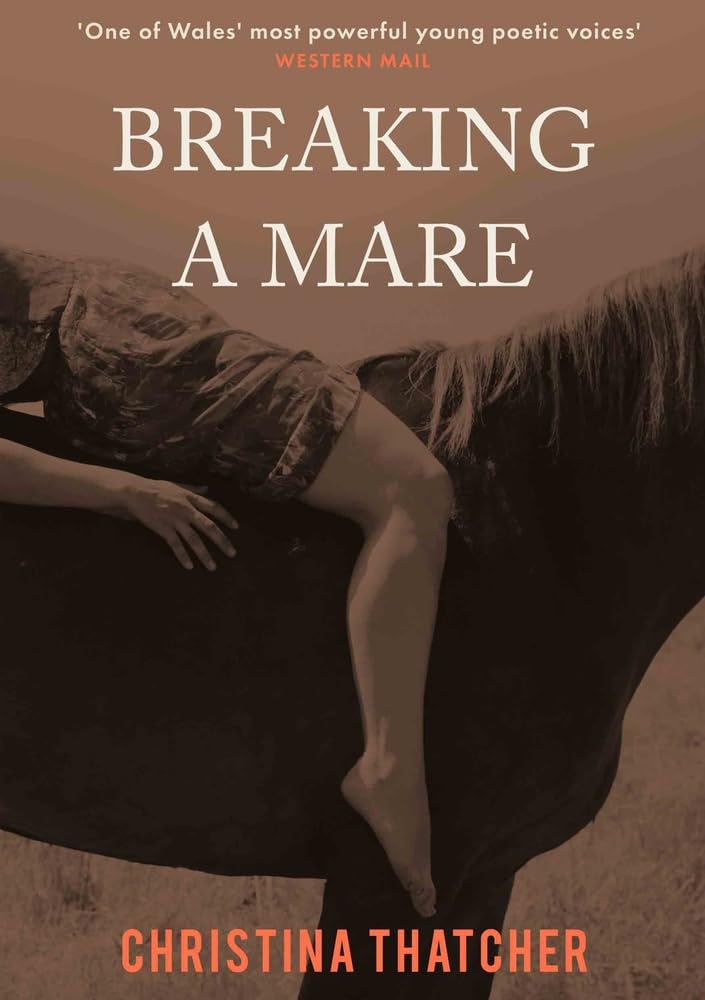

Breaking a Mare by Christina Thatcher. £10.00. Parthian. ISBN 9781917140249. Reviewed by John Short

There are feminist dimensions or implications within this collection (suggested in the title) which I don’t want to examine because they have been dealt with by other reviewers. Christina Thatcher’s poetry has a directness and a clarity that I find admirable: she tells it straight, although on occasion a little cryptic, stretching our deductive faculties.

The opening two poems seem to work in tandem. In Welcome to the Barn, any uncertainties as to why the pretty girls are braiding their hair or whether it refers to girls or horses, or why the clasps are solid silver, are clarified in the second poem, The Show, which is clearly about a performance spectacle or rodeo event where appearances are paramount as indicated by the last couplet:

For now, this just has to look pretty.

For now, this just has to be perfect

Throughout the collection we encounter the overbearing presence of the mother who controls and dominates the family. A formidable and powerful figure, almost masculine, but a little surprisingly, one means of control is through knitting, as explained in ‘My mother knits the Matriarchal Home’:

She is taller than all of us.

Her thighs like great grain barrels,

arms the length of pitchforks. Through

the power of needles, my brother is transformed

As the poem progresses it becomes a shade darker and more claustrophobic, like a scene from a Hitchcock film:

We wait at her feet as she knits our bedrooms: one pink, one blue.

She stitches a padlock for every door.

The poem ‘Hide and Seek’ is about rape and it echoes similar experiences of sexual molestation in Thatcher’s earlier collections. The skill here is how the deed is conveyed without a direct description. Instead, we get from the carefully chosen words, an evocation of a deep sense of betrayal, perpetrated by someone previously loved and trusted.

I thought you were just a boy, the same way

I was just a girl but I was wrong. I thought

you were calling me to climb the beech trees

with their slender, easy branches. I thought when

you took my hand you were leading me

somewhere comfortable. I did not realise

the moon had already risen.

It may sound banal to say that Christina Thatcher had a difficult life in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, USA before emigrating to Wales after winning a Marshall scholarship and settling in Cardiff to begin an MA and another theme is escape. In the poem ‘In praise of Fly Repellent’ we find her astride a mare that is being bothered by flies and one fly in particular. However, she still has hold of the bottle and is able to retaliate: Remember … watching the jet stream douse its wings.

And a little later, the conclusion:

That was the first time you saved yourself.

Can you remember what it felt like to escape,

your skin untouched? Doesn’t it seem like a dream now-

to remain unhurt, to gallop away

without being chased?

The collection could be described as nostalgic as Thatcher looks back and revisits her earlier horsey life. But it is a dark nostalgia bristling with menace and predictably sprinkled with accidents as in ‘It happened in Slow Motion’ which is a vivid description of one such accident: ‘Her tumbling off like a weakened acrobat / Her lungs deflating like a whoopee cushion / Her ribs folding like deck chairs.’ And later, in ‘The Rodeo Tragedy’: ‘Death was too slow for comfort / The crowd saw too much of trampled, pretty Bonnie.’

Another recurring theme is control as in ‘For all this filly knew, my mother was a mountain lion’: ‘How quickly she learned to succumb / ears jerked to my mother’s voice / eyes like trapped fish.’ And later, in ‘Private Lesson Ghazal’ which takes the form a set of riding tips or instructions: ‘The equine back is sensitive / loose seats encourage slack / Remember, this is about control.’ Thus we get a mirroring of the mother’s control of the family in essential features of the wider equine world. The mother’s temperament seems more than sufficient for dealing with both.

Continuing with the theme of accidents, the poem ‘Reanimation’ imagines a fatal accident in reverse, or rather it is the poet imagining the accident in a mood of deep regret. It is not immediately apparent what has happened and the clue is in the term ‘cannon bone’ which is situated in a horse’s lower leg between knee and fetlock. Consensus knowledge tells us a broken horse leg is almost always unfixable or at least economically unviable to do so.

Black. Less Black. The flicker

of long eyelashes. Blood dribbles back

to the bullet hole in the white blaze

of her face. Nostrils flare to the size

of tiny apples. A snort and her eyes roll

open. The cannon bone knits itself

back together.

The poem ends with a sharp sense of regret skilfully evoked, the pain almost palpable, but again without approaching the details of the event head on and we’ve all felt that sense of remorse and an intense longing to undo unfortunate events and have things back to the way they were before.

She gallops towards my voice, the field

greener than it’s ever been.

Christina Thatcher has summed up the collection as: an examination of girlhood in the context of farm work, horse rearing and rodeo riding. It is tough, unforgiving and as a previous reviewer commented: ‘Sexually charged and not for the faint-hearted.’ In the poem ‘Here we Are’ for example we can imagine only too well the kinds of people and the nature of farm life back then.

-women in my family take punches

throw them eat apples with too few teeth

tame horses and dogs drink milk jug cider

cry quiet so their children can’t hear

I enjoyed this collection, which requires more than one reading. At times puzzling and definitely not an easy ride. I wonder what will come next?

John Short lives near Ormskirk again after a previous life in southern Europe. Internationally published in print magazines and ezines, he has four collections of poetry and a book of travel stories. In 2018 he was a Pushcart nominee. His pamphlet The Company of Birds will be published by Cestrian Press some time next year.