Raymond Antrobus: Signs, Music • August Kleinzahler: A History of Western Music • Pascale Petit: Beast • Shanta Acharya: Dear Life • Charles Lauder: Year of the Rat

Signs, Music by Raymond Antrobus £10.99 Picador Poetry ISBN: 9781035020850. Reviewed by Maggie Mackay

Over the last year I have been drawn to the work and presence of Raymond Antrobus. His performance at the StAnza Poetry Festival this March was warm, inclusive, confident, and energising. I was bowled over. His musicality and lyricism are peerless. He needs to be heard.

My background is in education, in particular, curriculum support for mainstream learners with additional learning needs in the secondary sector so I have reason to be interested in the life experience of the deaf community. The actress Rose Ayling-Ellis raised the profile of sign language in recent times, creating an excitement and joy in the way hand signs can be expressed as musical notes. I find that a refreshing idea. And so this collection arrives at a prescient time.

In Signs, Music, shortlisted for the T.S.Eliot Prize 2024, Antrobus records his personal journey into fatherhood, before, in the first epic poem ‘Towards Naming’ and in the second ‘The New Father’ after the birth of his son. The stanzas run on like diary entries, a flowing consciousness without poem titles. There’s intimacy and immediacy in the thinking process which carry both Antrobus and the reader along. I’d say, a relaxed and conversational style invoking empathy and understanding, and exploring generational trauma.

He travels from Oklahoma, invoking a memory of threat, frozen roads and violence to London’s streets dense with ‘dads with babies strapped to their chests’, into Hebrew and Sanskrit – the meaning of Ira , into citing Genesis from the King James Bible to Kincaid’s poem inspired by Wordsworth’s poem on daffodils.

The first section/movement reveals his apprehension, his musings on his own drunk and semi absent father as a role model and as a caring parent, and his heritage. He considers the name to give his child. He vacillates between anxiety and hope, examines the state of society and turns to his parents for succour, his mother for the source of her name, his father for the meaning of ‘Seymour’. Neither response satisfies him

Amidst cigarette smoke at a café table of men, a faithful friend asks him the depressing question, implying doubt:

but why have children when the world is ending?

However, the expectant father’s mood improves:

the barista puts my coffee on the table

and sings out En-joy! like a musical doorbell

In the wake of persistent worry about naming the child, finding a flat and an anxiety ridden episode imbued with violence and freezing weather, Antrobus recalls his father singing ‘Three Little Birds’ to him :<

So I sing through the walls of your mother’s pregnant body

Three Little Birds, what my father sang

any time he saw my face troubled

And finally, at the end of this section, the name Ira is spelled out in British Sign Language through a diagram. The unnamed tree in the first poem addressed to Mimi Khalvati, is named, as the birch ‘bright, shining’.

In ‘The New Father’ section Antrobus grapples with the realities of fatherhood. He grows with his child .He tells us of small domestic details, walking through a park, noticing the natural world, point out objects of interest, imagining stories for passers-by, looking out of the bedroom window, bath time, lack of sleep and hints of domestic tensions. He comes to term with ordinary life and its extraordinary, unexpected developments:

I broke up

with announcing my convictions and good news

on the internet I broke up with talking to myself

as if I’m not there I broke up with people-pleasing

and the trembling boundary between life and still life.

His inadequacies as a deaf parent cause him anguish:

I see you turn to the beeping

monitor, your mother whispering,

the glowing phone

alert. Your eyes swallow the sound

that my ears can’t. Sometimes I’m afraid

that you won’t have the patience

to connect with your deaf father.

Will we become two people

in the same house, only

one of us sensing alarm?

But the magic connection with his child bring great comfort. Language and love come in many forms. The intimacy of sharing a bath with his son causes laughter . Tender moments and giant realisations:

I saw I had given him a sign name.

Fingers to eyes raising from thumbs – wide

eye meaning watchful of the earth

in two different roots – Hebrew, Sanskrit.

I love how he clings

to my shoulders and turns

his head to point at the soft body

of a caterpillar sliding across the counter,

and signs, music.

Signs,Music is a complex and remarkable collection. The poems benefit from being read aloud. They bear compelling witness to the speaker’s juggling of doubt and hope. There’s much musing over the influence of role models and the fear that hearing difficulties may create communication misfires in the future. We are left with the conclusion that the human mind can work through all these challenges with signs, music and connection.

Maggie Mackay is the author of one pamphlet, The Heart of the Run, Picaroon Poetry, and two collections, A West Coast Psalter, Kelsay Books, and The Babel of Human Travel, Impspired Press. In 2020 How to Distil a Guid Scotch Malt was awarded a place in The Poetry Archive’s WordView permanent collection. Her poems can be found in a wide range of publications online and in print, and most recently featured here: poets | wave 21 | iamb ~ poetry seen and heard.

*****

A History of Western Music by August Kleinzahler. £12.99. Carcanet. ISBN 97811800174931. Reviewed by John Short

Reading the recent Carcanet edition of A History of Western Music (Kleinzahler’s fifteenth collection) I was struck by the grandiosity of the title. In a video he explains that the poems were written across a time-span of over three decades until at some point, he realised he had enough to make a collection. The title was less than serious with each poem given a random chapter number to suggest the selection was extracted from a larger tome. The second thing noted was that the poems were peppered with obscure references. Was he addressing an informed circle or perhaps so culturally omniscient that this is his natural manner of expression? Cosmopolitan worldliness is attractive, providing it is not overdone and the reader feels shut out.

Many of the poems seemed inaccessible, however: ‘Zipoli and The Paraguayan Reductions’ caught my attention. Having grown up with Radio 3, Domenico Zipoli (1688-1726) is one of the few Baroque composers I was unaware of. An Italian from Prato, he became a Jesuit in order to work in the Reductions of Paraguay (missionary settlements) where he taught music among the Guarani people. The poem partly describes a river journey he made, possibly to take up his post in one of the inland settlements and it contains some lavish descriptions:

Scarlet and blue macaws soar overhead like brightly coloured hawks,

crimson carpets of verbena, devil’s trumpet, yellow datura.

The dark young Guarani boy in white, swinging the censer, tower bells sounding.

At times the lines read more like chopped conversational prose and in another section, referring to two antique keyboard instruments, one used for a recording of Zipoli in 1992, he continues:

Domenico Zipoli never heard or played on either, more’s the pity, but not for us,

one disc, and one only, currently available from Amazon for $99, a steal.

The collection has a random selection of subjects. There is no clue as to why these particular musicians have been chosen. Kleinzahler himself refers to the poems as: ‘free-ranging and from all over the place.’ The poem: ‘Eurythmics’ was initially problematic as I was wrong-footed by some minor historical details. It took a few careful reads to ascertain that it really was about Lennox and Stewart as there seems to be nothing on record to indicate that they were in Portugal in the early 80s or met the Nobel Prize-winning Communist writer Jose Saramago and one speculates as to where Kleinzahler obtained this (at times personal) information. Of Saramago:

He lived nearby. He wasn’t famous yet, just finishing up the Blimanda novel,

the one with Scarlatti. He’d buy us both a galao now and then, sweet man.

I can’t imagine he had much more than we did.

Nor we; famous, that is. Not quite yet. It wasn’t until the band let me sing.

No one was much into drum machines then.

Watching footage of Kleinzahler it’s curious how his modesty in interviews is at variance with the intellectual arrogance of many of the poems with their endless profusion of obscure names and exclusive references scattered like confetti. He appears to be addressing a select group of American cognoscenti with little concern for the rest of us who are not as amazingly well-informed. At times he lapses into melancholic brooding (‘In Memoriam Thom Gunn’) over private memories. The poem ‘Mahler/Sinatra’ had me puzzled until I learned that it was a chance connection. On arrival at Heathrow, late 90s, he heard the sound of Mahler’s adagietto and also Sinatra songs being played widely: ‘Sinatra was everywhere that spring / in the hotel lobbies, toilets, shops’ (It was Frank Sinatra week).

Many of the poems require some detective work in order to glean the sense. Understanding ‘Bartelby’ hinges on the identity of Winnaretta Singer, aka. The Princess Edmond de Polignac, heiress to the Singer fortune. The Polignac salon (1894-1939) was central to the Parisian artistic scene at the dawn of the 20th Century and most of the European musicians, now famous, were patronised by her. But who was Mme. Cornichon, who, despite an illness, outlived the princess and is oddly central in the poem? ‘She took sick and yet it was the princess / not she, who succumbed to a bronchial complaint.’ The young Ravel later dedicated his celebrated piano work, ‘Pavane pour une enfant defunte’ to Winnaretta Singer.

Some of the more enjoyable moments for me were the Jazz poems. In ‘Route 4’, Kleinzahler informs us that John Coltrane was a family friend when he was a kid:

It’s evening, after dinner, the family downstairs, doing what they do.

John will come by now and then and sit with me

on his way back from Van Gelder’s studio in Hackensack.

There’s a tender warmth in this childhood nostalgia. The kind of memories that most of us tend to cherish in later life:

whenever I’m a bit off, or in need of something, I don’t quite know what,

I play his Prestige sides from 1957, “Russian Lullaby” or “Traneing in,”

and think of my friend, John Coltrane, just sitting there beside me, listening.

Another of the Jazz poems: ‘Monk’ describes how the American pianist had the eccentric habit of leaving the piano in mid-flow (performing live) in order to dance. There were important critics in the audience. Was this madness or breaking boundaries: ‘His drummer and bass / puzzling through what he has left behind.’ Perhaps opening up to pure chance, the ultimate improvisation:

The large Black man, the large

Black man is dancing

And the Parisians are watching

Nervously. But the drummer, Pierre

That is, and Claude on bass

Are beginning to get it

Kleinzahler, born in New Jersey and later studying in Vancouver with Basil Bunting, has lived in San Francisco for over twenty years. A recent commentator described his work as ‘a reckless tumble of words mixing high and low art’. Others have labelled him elitist. That said, an American poet with cosmopolitan sensibility, his poems have an almost Beat flavour, recalling Kerouac and Ginsberg.

John Short, originally from Lancashire but with Irish and Scottish roots, has spent a large part of his life in southern Europe. Internationally published in print and ezines, he has also written one book of travel stories: The Private Unmentionable Gargoyle and four collections of poetry. The most recent is In Search of a Subject (Cerasus 2023). He appears at open mic venues around Liverpool and used to read on Vintage Radio, Birkenhead. He is finalising a new collection.

*****

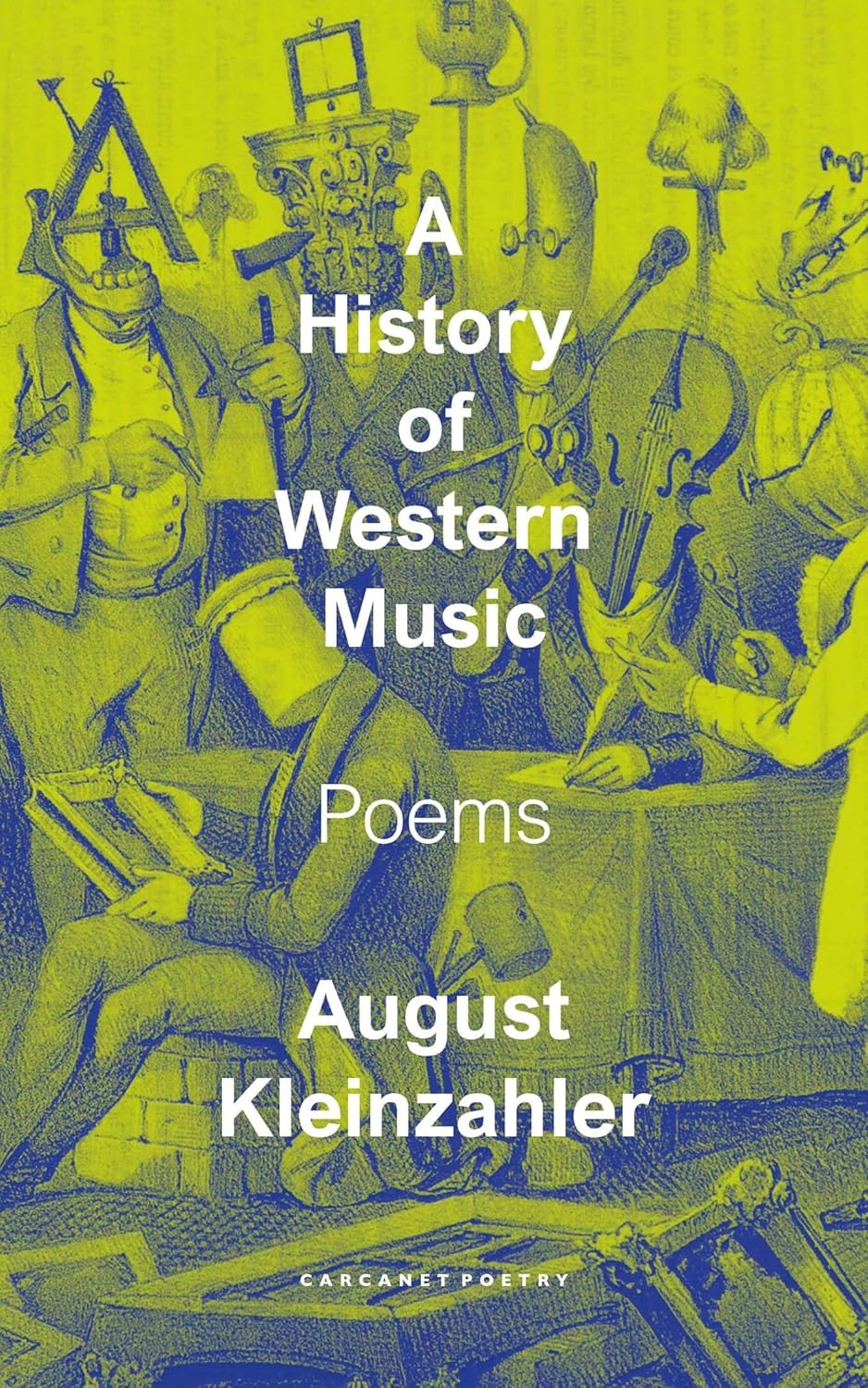

Beast by Pascale Petit. £12.99. Bloodaxe. ISBN 9781780377377. Reviewed by Emma Lee

Beast explores whether survival of a sorts is possible for children who grew up in abusive family and are trying to break the cycle of abuse, and for animals (including humans) on an abused planet in the midst of a man-made climate catastrophe. It’s not all doom and gloom though, some of these poems are lyrical celebrations of the beauty of nature. It does need a content warning for historical sexual abuse and assault. The collection is split into sections “Amazonia”, “The Camargue and Languedoc”, “Tala Zone” which is a prose sequence, “What Rough Beast?” and the “Beast of Bodmin”. Those familiar with Petit’s work will recognise the use of animal metaphors for traumatic experiences, drawn from her past. From the opening section, “Maman” (after Louise Bourgeois), considers the poem’s speaker’s mother as a sculpture of a giant spider:

I mean the giant ogress

who hangs at the dense

heart of my universe,

whose space-time grid

is a sticky gold web

I blundered into just as

she was swaddling that

vine snake my father –

he who threshes in her silks.

This maman is not a maternal, nurturing mother. Another poem in the collection describes how her mother, working as a hotel chambermaid, was assaulted by a guest and became pregnant as a result. The mother in “Maman” is a mother but not willingly. This is a woman who was made to be a mother against her will and had to deal with not just raising the resulting child but dealing with the constant reminder of how the child came to be. The mother feels as trapped as the child.

The father, however, has a freedom, in “The Insect Father”:

While I was a baby, you became a botfly

which bored through my fontanelle, lodged in my brain.

So when I learnt to talk, I named you:

Yellow Jack, Blue Devil, Black Vomit.

I watched you fly away from my childhood

to eat the face of God.

The poem’s father is a source of evil, “Yellow Jack” a condensing of yellow jacket, a word for wasps, “devil” and “black vomit” need no explanation. It’s beyond the scope of the poem to explore whether the very young girl is forming her own opinion or has been influenced by her mother. Either way, the father doesn’t appear to have recognised the situation he’d set up. He drifts in and out of his daughter’s life, only showing interest,

And when I had to pass to womanhood,

you were the mat of wasps

applied to my chest until my breasts grew.

The father uses the daughter in the same way he used the mother. Later, in the next section, he is enchanted by the “Beast of Vaccarès”,

Then they turned and race counter-clockwise,

their hides glinting with starlight.

And then what? I asked. Ah, that old beast

who roamed the tangled islets of Vaccarès

was swallowed by the Bull-drowner – that pit

of quicksand. Then my father became quiet,

and never again spoke about the Beast of Vaccarès,

or his beloved Camargue where flamingos flock

like symphonies of blood, or the hoof-drums

of wild black bulls with harps for horns.

But I’d seen the moonlight in his black eyes

and how he breathed easily for one, breath

that now sank into the quagmire of his lungs.

I sat opposite him every mealtime, hoping

for another tale, for there are many monsters

in that delta, and after every dessert, I peered

into the abysses of his black eyes

but all I glimpsed was my own face drowning.

What starts as a story to enchant his daughter, creating a bond between father and daughter, becomes something else. The beast sinks in quicksand and the father falls silent, no longer giving his daughter stories. Meanwhile the daughter is left hoping for more. But her father has checked out, his eyes give a reflection of her face, but don’t open to provide the connection the daughter desperately wishes for. Abused children often snatch at anything that might show something that could be seen as love: the shared story of the bull offering that moment of connection. Then it is withdrawn, leaving the child hoping for another story, but the parent isn’t emotionally mature enough to recognise what he is doing. Another poem details how the father was abused as a child but repeated the cycle of abuse as an adult rather than breaking it. The lack of reflection on his part hinted at in the “Beast of Vaccarès”, as his daughter can only see her own face, but his internal thoughts are “the abysses of his black eyes”. The colour echoes back to “The Insect Father” and one of his names, “Black Vomit”, a man who attempts to control through fear, perhaps who identifies with a bull, but falls silent at its undignified death by quicksand.

That impulse to control through fear is a motif in the section “Tala Zone”. In part I, the daughter is sent down to the cellar:

I’m in the cellar’s forest and the moon is shining. Between me and the moon there’s a man with a cloth over his face. Is it you, Father? I never thought it was you when I was six, but I’m grown-up now. It must be you, because who else would have sent me to the cellar, told me to count to a hundred but not to go down to the very end because a fire was there with tigers leaping out?

The now adult daughter is reflecting back to her childhood and trying to make sense of things that were just accepted at the time. This section is complementary to parts of Petit’s novel “The Hummingbird Father” (Salt, 2024), where the novel’s protagonist visits her terminally ill father and memories of childhood, including being banished to the cellar, surface. “Tala Zone” ends by exploring how by probing into the dark spaces, of the cellar and the mind, the child taught herself how dark and light are complementary, how knowledge brings resilience, how survival might be possible.

The possibility of survival is picked up in “Butcherbirds”, which mentions Palestine where “instead of bombs”, storks build nests, and:

I know that sparrows nest under a stork’s eyrie,

keep mosquitos of shrapnel from their hosts’ chicks.

The commonest bird can be the most lyrical, when

she perches on a warhead that hatches only song.

The cooperation between the birds against an enemy enables survival and even the lowliest of birds can take part and contribute. Bird feature later in “Swallows” where the poem concludes:

I gather white feathers that float down

like summer snowflakes from your beam.

My fingers grip the pen like an overhead wire.

What is this letter I’m writing on paper

new as a fledging’s breast?

What are these insects I feed my pages?

Art can be transformative. It can help express the indescribable and help the artist reach an understanding of situations that are hard to comprehend such as two parents inflicting damage on their child, a mother who is not maternal, a damaged father visiting the abuse he’d suffered on others and the consequences for an unloved child. The child who has to understand her past to forge a future.

Petit uses the plight of endangered animals in a climate catastrophe to explore intimate abuse and personal concerns. The poet sees art as an act of hope, a way of making sense of the past and connection with the present, an act of resilience when the future looks hopeless. “Beast” is a portrait of a savage painted with a sharp eye for detail, crafted for connection and reaching an understanding of a creature that doesn’t play by normal human rules but nonetheless deserves to survive. The poems are lyrical and deserve re-reading.

Emma Lee’s publications include The Significance of a Dress (Arachne, 2020) and Ghosts in the Desert (IDP, 2015). She has joined panels and written papers on artistic responses to the refugee crisis arising from her co-editing of Over Land, Over Sea: poems for those seeking refuge (Five Leaves, 2015) and curation of Journeys in Translation. Currently she is President of Leicester Writers’ Club. Her poems and short stories have been widely published.

*****

Dear Life by Shanta Acharya. £8.95. LWL Books. ISBN: 979-8-218-46529-2. Reviewed by Stephen Claughton

In this, her eighth poetry collection, Shanta Acharya confronts an uncertain world, one in which she’s had to endure not only the Covid pandemic, but also her own ill health and her brother’s untimely death from cancer. In writing about it, she brings to bear her own particular mix of stoicism, mysticism and humour, combined with imaginative sympathy.

‘Being Alive’, with which the book begins, describes a CT scan (‘Moving through the scanner my body lights / up in a scrum of pain, building images // like slices of a loaf of bread of each organ’). Her ‘body now branded with the world’s // suffering’ and with medical experts unable ‘to diagnose the cause of my grieving’, it’s left to her to ‘heal myself with love, touchstone of the universe’. The title poem, with which the collection ends, makes it clear where her love lies:

I have nothing else to offer, dear Life—

words are what I breathe and eat, the clothes I wear,

dreams that sing me to sleep, silence that greets me awake:

words are the only wealth I possess—my truth, my love.

(‘Dear Life’)

Many of the poems take the form of interior monologues, reflecting both the enforced self-isolation brought about by Covid and her natural inclination. As she says:

Not knowing when the pandemic will end,

I accept solitude as a path to staying alive—

the conversation with oneself necessary as ever.

(‘Staying Alive’)

But her meditative poems aren’t a form of hermetic navel-gazing. She lets in the real world: ‘Shocking the sight of empty shelves in supermarkets. / The extra fine veneer of civilisation stripped / in a heartbeat with talk of lives not worth saving.’ Poems about dressing up alone during lockdown or finding dead bees in a gas boiler (in a sequence of unrhymed sonnets about the pandemic) sit alongside more abstract poems about keeping hope alive or the desire for religious faith (‘with my prairie-open mind’). Her feelings are often expressed with a confessional directness:

Why did I think it normal to crawl on the floor

of the ocean of exhaustion, hoping for redemption

. . .

Single, female, first generation immigrant, no security,

intelligent, neurodivergent, born to be different.

(‘Looking for Myself’)

Personal poems are mixed with others that address social issues. ‘A deadly virus held a mirror up to society, / revealing the extent of our inhumanity’, she says in ‘Strange Bewildering Time’. ‘Nesting’ describes a case of domestic abuse, which increased during the pandemic. ‘I Can’t Breathe’, about the killing of George Floyd, plays on the fact that the victim’s asphyxiation by Minneapolis policeman, Derek Chauvin, happened during the pandemic, when Covid victims were also suffering an inability to breathe.

Despite the seriousness of her subject matter, she is also capable of wry humour. Hearing someone in a hospital waiting room say:

One of the problems of growing old,

Isaiah Berlin once told Jeremy Paxman,

is not having any friends left to lunch with.

Unsure she was talking to me, I replied,

trying not to sound like Tina Turner:

What’s age got to do with it?

(‘The Waiting Room’)

While some poems are contemplative and abstract, others are more earthbound, such as the deliciously tactile ‘Taste of Childhood’, in which her madeleine moment is the opening of a pomegranate, or the equally sensuous, ‘This Is Where We Learn What It Means To Be Human’, about learning to cook in her Indian homeland.

Visiting her home city of Cuttack, she suffers insomnia due to jet-lag (‘Wokeness’) and visits the former headmistress of the convent where she was educated, now sadly suffering from dementia. We find her on a train in ‘Moscow To St. Petersburg’, or people watching at an airport in ‘Departures, Arrivals’: ‘Waiting at Baggage Claim I watch the theatre / of humanity unfolding as in an Advent Calendar. // The conveyor belts move like waitresses, / balancing their heavy plates of hors d’oeuvres—’

Other poems take on major events—the Holocaust, the Partition of India, the Bataclan attack, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the destruction of Aleppo, climate change—not in a generalised way, but how they impinge on private lives, or could impinge (‘Do not presume it will not happen to you— / bad things happen to good people. // Think of what you can do in the face of calamity, / not to be overwhelmed by its immensity’, she says in ‘It Happened’, which has an epigraph from Primo Levi: It happened, therefore it can happen again.) Her imaginative sympathy is engaged by the fact that, as an emigrant herself, she knows what it’s like to be an outsider: ‘feel my heart / beat with the compassion of one in self-exile,’ she says in ‘Exile’. Returning to her roots, she has a number of poems about Indian history and myth. The glossary and notes are helpful with these and others in the book.

Two of the most moving poems in the collection are those written in memory of her brother. One, ‘We Are All Returning’, is an elegy in five parts, celebrating his life and courage in the face of death, as well as her loss: ‘The most revolutionary thing one can do in the worst / of times is to live and love to the best of one’s ability.’ The other, ‘Where Did He Go’, is a shorter poem based on Rumi’s ‘Where did the handsome beloved go?’ (one of several ghazals in this collection).

Shanta Acharya’s poetry is marked by its intelligence, courage, honesty and above all its versatility. She is by turns meditative and mystical, humorous and grounded. I liked best the poems that were most deeply rooted in the physical world, although there is enough variety here to appeal to all tastes.

Stephen Claughton’s poems have appeared widely in print and online. He has published two pamphlets, The War with Hannibal (Poetry Salzburg, 2019) and The 3-D Clock (Dempsey & Windle, 2020). He reviews poetry for The High Window and London Grip and chairs Ver Poets in St Albans. Links to his reviews, poems and pamphlets can be found at: www.stephenclaughton.com.

*****

Year of the Rat, by Charles Lauder. £7.00. blueprint press. ISBN: 0781739369545. Reviewed by Wendy Klein

Brought up in San Antonio, Texas, editor, poet and ex-pat American, Charles Lauder has a keen eye for the political, the personal (family). and nature. A follower of Tao Buddhism which stresses the importance of living in harmony with the universe, all are key to his work. The scope of this pamphlet, his third, is immense for its size – 21 pages. Each poem is of a quality that deserves a level of attention and commentary not easy in the space normally allocated for a pamphlet.

The opening poem is titled ‘September 24th’, Might that be 2020? A rat year and a pandemic year would be a coincidence too interesting.to overlook. In mythology and folklore, the rat symbolizes abundance and prosperity. In some cultures, rats are regarded as symbols of wealth and fertility, stemming from their ability to find and store food, in scarce, even plague conditions. A sense of survival and fear is threaded through these vivid, often philosophical poems which include a sequence of 8 poems about Lauder’s rat year in the year of our great plague.

24 September 2020, was the date when, among other rules set out to control the pandemic, the prime minister laid down a set of social restrictions. Particularly contentious was the rule of 6, limiting all social gatherings to six people. On this day the poem family bade farewell to their old upright piano: ‘busted apart in their kitchen’ and took delivery of a baby grand. Change is afoot — the tuner: ‘taps a few keys, sprinkles out / notes, then when satisfied he plays as:

Autumn leaves cover our drive

and fill our dining room.

The startling image of autumn leaves in the dining room is followed by a poem in which the family dog breaches the boundaries of semi-derelict Bruntingthorpe Air Base in Leicestershire where ‘the crumbling runway’ is ‘booby- / trapped by Charolais cowpats.’ Angst fills the evening as: ‘Bullocks bellow alarm’ stampede and – ‘under the base hospital ruins // a mountain of slabs graffitied in unsteady red / of dick sizes’ which Lauder suggests was a hideout village boys outgrew. The grotesque scene is contrasted nicely within the containment of formal tercets, finishing with the dog ‘Unable to catch any prey… inspecting droppings around a fox hole.’

The dog reappears in the following poem, ‘Outside the garden gate’, where curious encounters take place with neighbours never previously spoken to until he bounds over. Here the strangeness is heightened by fairytale imagery: ‘chickens greedily sailing into next door’s vegetable bed / like children through the gate of a gingerbread / house’ or ‘you and I knocking on the door / and stepping into a witches coven…’ — a poignant reminder of the odd quality of relationships evolving between neighbours during Covid.

The 8 rat poems near the centre of the pamphlet catalogue an infestation in the poet’s family space, actual rat(s) in the rat year. Ranging from their discovery when the woodshed door first appeared ‘worn away like a riverbank / like the ancient pages of a mystic’s text, through varying degrees of destruction and death: ‘this Gordion knot of petrified rat pups’, the poet comments on their death without a parent — said parent found dead under the dining room table. Rodent bodies are found partially devoured by the family cats, but alongside the gore he muses on rat-ness in an almost elegiac way, highlighting their ingenuity, their plight, their ‘pleas’ heard in the night. While wishing for a Pied Piper, he shows a certain fascination with the creatures, one of which he rescues from drowning in a bucket (poem vii). Reflecting on the traps they were offered which: ‘snap necks, mangle arms’, and seeing a less painful and horrific way of doing away with one, Lauder finds himself tempted to leave the creature in a bucket of water, but his knowledge that ‘rats can swim for days’ stops him, and the rat is loosed in a nearby field. The rats remain, and poem viii ends with the lines:

The only way to feel safe is to light

a fire and hope the woodsmoke nourishes us.

The sense of unease persists through the meditative ‘Conversations with God’ in which the poet explores the many ways in which we attempt to communicate with one another and the unknown ‘other’. Deeply intense, it could relate to the sense of alienation engendered by Covid, concluding with:

We speak across an impertinent emptiness

that brings no peace-of-mind, no resolve about the other.

In ‘Enduring Winter’ a poignant bird sonnet, the poet explores the hazards of cold, concluding with lines that perfectly depict the pandemic’s ending: ‘For a while all remains distant and still. / The brave creep back in, resume foraging.

Of the next three poems, ‘The Making of a Pirate Queen’ is the one I found most captivating. Who can resist a girl: ‘who spies in a mirror a gene gone awry / and sets off in her own sloop’? The pirate / nautical imagery is sustained throughout from: ‘How comfortable she is among castaways’ to the enchanting portrait:

She tied a bandana around her head,

clenched a sword between her teeth,

raised a black flag and steered

the dining table toward the far horizon.

Two concluding poems explore family relationships through the lens of Tao. ‘Yin and Yang’ depicts a marriage, one imagines the poet’s own, in snapshots that complement one another across the page. Then ‘Galveston, Texas, 1900’ evokes a hurricane without warning, like a pandemic without warning and is rich with family history.

The final poem, ‘In search of silence’, is reflective as the poet creates his own narrative: ‘I want to lie down in a field and disappear’, and ‘Here pheasants will build a nest / and wait and wait for the world to change.’ As do we. Charles Lauder offers an earthy poetry, both lyrical and expressive. He explores terror and wonder simultaneously in unique, memorable verse, a compelling story of our time.

Wendy Klein, a retired psychotherapist, born in New York and brought up in California left the U.S. in 1964, and has since lived in Sweden, France, Germany, and England. Despite having 4 daughters and 14 grandchildren, she has published 4 collections: Cuba in the Blood (2009) and Anything in Turquoise (2013) from Cinnamon Press, and Mood Indigo (2016), from Oversteps Books, Out of the Blue, Selected Poems (2019) from the High Window Press, and one pamphlet, Let Battle Commence, based on her great grandfather’s letters home while serving as an officer in the U.S. Civil War (Dempsey & Windle, 2020).

*****