*****

Latest Reviews

Mimi Khalvati • Patrick Deeley: Keepsake • Marie Howe: What the Earth Seemed to Say: New & Selected Poems • Iana Boukova Notes of a Phantom Woman • Fatemeh Shams: Hopscotch • Quentin Cowdry: Close-Up • John McKeown : The Chain Bridge • Isabel Bermudez: Bar de Las Reminiscencias • Katy Mack: First, I Turn Off the Light • Linda McKenna: Four Thousand Keys • Rachel Spence:Daughter of the Sun • Siegried Baber: The Twice-Turned Earth

*****

Reviews published since the previous full issue of The High Window

Pat Boran: Hedge School

A Bird called Elaeus: poems for here and now from The Greek Anthology, translated and arranged by David Constantine • Philip Gross: The Shores of Vaikus • Claire Dyer: The Adjustments • Rachel Carney: Octopus Mind • Marin Bodakov: The Chaos of Desire • Nia Broomhall: Backalong

Sarah Holland-Batt: The Jaguar: Selected Poems • Helen Ivory : Constructing a Witch • Susan Utting: The Colour of Rain • Ghareeb Iskander: English Poetry and Modern Arabic Verse: Translation and Modernity • Julian Orde: Conjurors • Sam Smith: Mirror, Mirror, In the Geography of the Head • Caroline Maldonado (Poems) and Garry Kennard (drawings): Michelangel, Mirror and Stone

Fabio Morábito: Invisible Dog • Jenny Lewis: From Base Materials •

Dunstan Ward: Departures

Jane Hirshfield: The Asking: New & Selected Poems • P.W. Bridgman: The World You Now Own: New Poems and a Novella in Verse • Mike Barlow: A Land Between Borders • Victoria Kennefick: egg/shell • Lynne Wycherley: Alighting in Time

Rory Waterman: Come Here to This Gate • Amy Abdullah Barry: Flirting with Tigers • Jack Little: Slow Leaving

*****

Collected Poems by Mimi Khalvati. £30. Carcanet Poetry. 9781800173330. Reviewed by Sam Milne

Mimi Khalvati’s Collected Poems is a finely produced book, comprising all eight of her volumes of poetry published since 1991, plus twenty-four uncollected poems which alone constitute a considerable body of verse. The poetry is of a very high calibre indeed, a substantial achievement as there is something like five hundred poems gathered here over six hundred and twenty-nine pages.

An important point to start with is to point out that nearly all of Khalvati’s poetry is based, or receives inspiration from, music, especially song. This observation applies to her free, or open, verse as much as it does to her use of stricter poetic forms such as the ghazal and sonnet. (The sonnet for her, I surmise, is a Western equivalent of the Middle Eastern ghazal, both relying on musical motifs and disciplined frameworks.) The balance of excellence (for me) falls on the side of the traditional genres rather than on the free verse poems which are typical of her early work. Her adoption of strict configurations (‘disciplined forms’ Norbert Hirschhorn calls them in a review of her work) suits her talent better. As an Iranian-born British poet she bases her work on a deep knowledge and experience of two extensive literary traditions, what she calls in her poems ‘a confluence of roads’, constantly ‘cross-pollinating’ or listening to ‘ancient voices.’ The depth is apparent in equal measure, intellectually and emotionally, in her poetry. Poetic technique is very important to her then, a quality missing, unfortunately, in much of today’s poetry. Often employing the radif (the word occurs in her poem ‘Ghazal: It’s Heartache’), a term used in Persian poetry that refers to a recurring refrain or phrase that appears at the end of a verse or couplet, this device is used by her very effectively to create musicality, enhancing the emotional impact of the poems she writes. Her sonnets and ghazals in her long sequences, for instance, often sound like song-cycles, intertwining at the same time like crowns or garlands, or cohering like prisms or lattices: ‘How lucid every arc, every plane…reflecting facets I have lived’ she says in ‘A Thank-You Letter’, ‘to enter / a single sound… to love / each sound, each sound’ as she phrases it in ‘Tintinnabuli’. This interconnectedness is also evident in her free verse, as in this short stanza:

Writing In The Sun

is a kind of blindness:

blinded by the sun

and blinded in the shade

(‘Writing In The Sun’ is the title of the poem.) This kind of compression was called ‘concatenation’ by T.E. Hulme, and he thought it the true essence of poetry, as it ‘refreshes the word by new associations’. Hafiz is her favourite poet, perhaps unsurprisingly, as he perfected the private form of the ghazal (khalvati in fact means ‘a quiet retreat’ in Farsi, which suits the poet’s temperament perfectly, her poems ‘windows / looking forever inward’). The meditative timbre of the ghazal suits her then, with its mix of secular and mystical themes (she avoids the more public qasida form preferred by Rudaki, for instance). The orthodox sonnet is adopted by her, I think, because of its probable roots in the Middle East, the Sicilian poet Giacomo da Lentini mentioned by her in ‘In Praise of The Sestet’ (unfortunately misprinted as Lentino) having first created the form in the thirteenth century, merging Middle Eastern and Western traditions in the way she herself often does. Although the sonnet and ghazal forms are evident in some of her early and middle work, their use becomes more consolidated and refined in her later volumes, where she strips her earlier (at times) prolix style down to ‘the bare bones’ as she calls it in section nineteen of Entries On Light (the book comprises one long sequence of interlinked themes) creating a ‘scaffolding and ark of spoken speech’ as she expresses it in the poem ‘Handwriting’. It is this committed approach to classical composition (‘Marshal your pencils then, master your fear’ she writes, translating Lorca) which ensures her poetic themes always carry emotional and intellectual weight. ). She writes that she aims for ‘the simplicity of frost… the clarity of snowflakes’ (in ‘Life in Art’) but one feels this is only an (acceptable) idealization of her poetic intent.

The ‘blurb’ to the book tells us her central themes are ‘the loss of her native country, culture and mother tongue [Farsi]’, her own memories of that loss and the ‘central void always facing’ her’. Although I think this is true (‘the colours of my childhood, needed more than ever…. verandahs… half-remembered’ of ‘Evergreen’; ‘I don’t know where I live any more ‘of ‘Whittington Hospital, March 1990’; ‘the unnamed griefs… abandonment… the day’s debris’ of ‘Background Music’) there is more to her work than just that. For me her poetic mind concentrates mostly on those subjects we associate with the ghazal and the sonnet (‘Without my love, there is no song’ she writes in section four of ‘River Sounding’), longing, the brevity of union, and art’s capacity to surmount nature. These are ‘the gradations of feeling’ she writes about in ‘Very’, and the art of writing poetry is what enables her to overcome the ‘phantoms and daemons’ she writes about in ‘The Ice Rink’ for example. Her favourite quotation is from the work of the Urdu poet, Faiz Ahmed Faiz, who wrote ‘the true subject of poetry is the loss of the beloved’—the classical subject of both the ghazal and the sonnet.

It is the humanity of her verse that stands out for me, something we are in much need of in this time of power conflicts, reminding us always ‘of what it is to be human’, of the ‘cries of women’ as she phrases it in ‘Woman, Stone And Book’, of ‘human warmth’ as she puts it in ‘Shanklin Chine’, seeking safety and comfort, caring for children as she writes lovingly in ‘La Belle Dame’: ‘Come here by the fire. / Let me smell your hair’. Elegy is there too, and grief, in her poetry, as in ‘The Poppy Signals Time To Scythe The Wheat’, on the death of her father: ‘The day he died my mother cried all night, / her tendrils round me, wound towards the light’—or on the death of her mother: ‘She’s gone to ground with all manner of creation: / mole and beaver, wren and starling, flown tenants / of earth and air’ (in section three of ‘Malih At St Mary’s’). She is also very good at shocking the reader, as in these words of an old woman: ‘Will my fingers never smell of sex again?’ (in ‘Confusing Arrivals with Departures’). Her detailed observation of nature is always to the fore, and is as keen at times as that of Marianne Moore or Elizabeth Bishop: ‘A yellow ladybird is reading The Guardian Weekend, / alternately reading and grooming, rubbing her hands, / slapping the sides of her face’. One of my favourites is a picture of a mouse with ‘miniature paws like nail clippings, hind legs crossed / in a rather elegant fashion, tail a lollipop stick…her shut eye a tiny arc like the hilum of a broad bean’. These minutiae have a light, humorous touch to them, and are extremely memorable.

It is comforting to know that in England Khalvati has ‘found, heaven knows, / a bed and a roof ’, although at the same time regarding herself as a kind of chameleon, someone who is always trying to blend in with her surroundings (see her poem ‘Chamaeleonidae’), placing herself where she can feel safe and sure. ‘However large earth’s garden’, she says, ‘mine’s enough’ (in ‘Ghazal After Hafiz’), the garden a metaphor also for her poetry. The garden, of course, is an abiding theme or image in Persian poetry, and it is there she likes ‘catching the sun in flight’, cherishing the sight of birds and flowers, the flow of water and ‘the life of shadows’—‘the gentleness of light’, ‘the mosaic of light’ as she calls it. She is also very good at interior scenes, places full of ‘odours, whispers, mirrors… a summerhouse of six rooms, / in every room a fireplace’ (‘A View of Courtyards’), ‘Emily Dickinson sat in her room / and the galaxy unrolled beneath her feet’ (‘Iowa Daybook’), analogous to her own love of the garden as a place of inspiration. Mimi Khalvati’s poetry moves from fragmentation (her own divided allegiances and legacies) to unity, a resolution that brings peace at last:

Visit me.

I am always in

even when the place

looks empty,

even though the locks

are changed.

(from ‘Song’, in her fourth volume, The Chine)

In her poem ‘Lyric’, writing about her childhood reading, she asks: ‘a lyric couldn’t do what birds do, could it?’. And she clearly believes it can.

Above all else Mimi Khalvati is a lyric poet who, over four decades, has asked herself that question time and again, expanding that lyricism whilst continuously experimenting with poetic form, as in this excerpt from Entries On Light:

Today’s grey light

is of

light withheld but

softly

shyly like a sheltered

girl’s.

That softness, that light, that shelter, are all hallmarks of her work. Her love and her care for people are also clear in her striving for technical perfection in her poetry. Hafiz’s ghazals (she says in her late poem ‘Blessing’) are a ‘beloved form… a burning spark… between the living and the dead’. I think the same can be said of her own poems. They will extend in time, beyond the current generation.

Sam Milne is a Trustee of Agenda and has been a regular contributor to the magazine. He is an Aberdonian living in Surrey. He has just finished writing a play on the Scottish communist, John Maclean, and has recently completed a translation of The Iliad in Scots.

*****

*****

Keepsake by Patrick Deeley. 12.50 euros (£8.49 via Amazon). Dedalus Press. ISBN:9781915629234. Reviewed by Patrick Lodge

In his 1901 preface to the collection “Poems of the Past and Present”, Thomas Hardy wrote ‘unadjusted impressions have their value and the road to a true philosophy of life seems to lie in humbly recording diverse readings of its phenomena as they are forced upon us by chance and change”. Hardy, of course, denied that there was any coherent philosophy behind his poetry; that it was, merely, ‘unadjusted impressions’ and this lack of a “harmony of colouring’ allowed him to challenge successfully any charge that he was essentially a pessimist. For Hardy life was dominated by variety and diversity and was basically too complex and inconsistent to grasp with any firm sense of having got the message. Patrick Deeley, the prolific and award-winning poet, novelist and memoirist, might well agree with Hardy on the evidence of his eighth collection, “Keepsake’. Deeley has noted that the events and circumstances of his life present but “ general emotional and psychological thickets through which he has to find his way” and this collection is delightfully crammed with impressions of many aspects of life – childhood, ageing, the natural world, friendship, memory, travel – and, while no didactic philosophy is forced on the reader there is a consistent tone of openness to experience, of hope and joy, of lyrical acceptance and profound gratitude. As Deeley succinctly put it in a 2019 interview with Patrick O’Donnell, “I still hold the possibility of wonder as I did as a child”.

Deeley’s madeleine might well be a Ferguson TVO tractor which he recalls in his memoir “The Hurley Maker’s Son” and which both starts his poetic approach and carries it through in characteristic style– “I dream the vaporous progress the old steam engine makes through the blackened sawdust of the past ”. Deeley grew up on a farm in the Callows, a wetland meadow – “thin-skinned, dangerous, primal’ as he once said – in the east of County Galway. It is doubtful whether this rural Galway past, and the Callows in particular, have ever left Deeley – he once described Nature as “the one constant on which we rely”. In contrast, his working life was far from rural Galway in Dublin and as Deeley himself said, he has been “trying to marry them since’. While the late, and much lamented poet, Fred Johnston, has written on Deeley’s “two-souled poetry”, this current collection evidences little of any tension between the poet’s rurality and his Dublin life – the former seems always to win out .The Callows were, in Deeley’s memorable phrase, “the start of wonderment” and nature, in its broadest sense, continues that wonderment, though with no eco-preaching rather a gentle, though no less powerful, sadness at ‘the way we wear the world / of wildlife thin…’ (‘The Keepsake”). The tone is, unsurprisingly for an eighth collection, more reflective, anxious almost, compared to the first experiences of rural Galway and the Callows, the little wilderness, as Deeley put it, “my own personal outback, the place where I could lose myself”. Deeley’s poems recognise the changing world he inhabits but, like the shell-less egg of the title poem “ might prove a counter or a stay”. (“The Keepsake”) to its worst excesses.

There is always an earthy quality to the poetry – Fred Johnston described it as ‘rich as loam’ – that grounds the reader in lived and fully understood experience and also, the recognition that, though we cannot comprehend fully we can strive: “the measure of many things is beyond us, / to live is to reach for…” (“A Liberty in Kilruddery Woods”). Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote powerfully of the land “as the appointed remedy for whatever is false and fantastic in our culture”, a “tranquilizing, sanative” influence. While Deeley may not be able to see his rural past with the same wonderment, he can recognise the truth of Emerson’s comment. A regular morning chat with a Dodder River tree – in which the tree’s seasonal changes become part of the conversation and Deeley’s contribution is “a smile when I catch sight of a kingfisher / igniting your branches” – has its sanative contribution to make, “And I find I am clear then // of doomster notions positing the future / as being all of mayhem, everything of murder.” (“To a Dodder River Tree”). Or the robin that lands on his spade halfway through a poem that commenced with the collapse of rusted ironwork outside a derelict shop – no sentimentality here as the robin in taking off may brush Deeley’s cheek. No affinity signalled but even so “…I break / into a quickstep at its casual happening”(“Affinity”).

Reading this collection is like walking down an ancient boreen with the end out of sight, the twists and turns inviting, the way full of surprises and natural companionship – as Deeley observed about the Callows, “I never felt less lonely than when alone there”. There is a sinuous quality about the poms – they may start in one place but wander about until asked to deliver their full meaning. Their journey intrigues, fulfilling Deeley’s own view in a 2016 interview that “if writing is any good it has to surprise its author as much as the next person”. Thus “But Mercy” starts with the joy of a murmuration – a “flex of ecstasy” – moves on to a dyslexic child and concludes with seamlessly with a schoolboy suicide. Deeley is a poet who takes nothing for granted, is curious and explores, teases out, sees the telling detail, makes connections in an effort to make some sense of it all. “Altars” starts at Pompeii where Deeley is grabbed by a “red leafed weed” at base of the altar of Apollo and this hint of a blood sacrifice segues into him serving at a Station Mass in his childhood home and then further to the marble altar of his parish church. For Deeley God seems to be everywhere, in the forest, the ring-fort hill, a barn-door laid down on which pigs are slaughtered, “in a crucifix kissed, a stone throw / on a cairn of stones, votive rags / tied to a hawthorn tree?”. A complex, seamless serpentine poem of associations and thought characteristic of this collection – the final interrogative suggesting less hints of pantheism than an unremitting curiosity that drives these poems; a curiosity that, as Fred Johnston put it, “like a lighthouse beam … scours the elemental places…for recognition and the flags of the familiar”.

One of the joys of this collection is the language – never forced, never fussy and rooted, like so much else, in his childhood. In his memoir, Deeley recalls his father trying to make him a carpenter but he is more fascinated by the sounds of the esoteric language describing the skills and techniques, hallowed by age and usage, which later, “came back to me not just as belonging to him but as sounding poetic”. Deeley recalls as a child, at the end of the day, laying back in his mind the images from nature he had encountered in the day. He sees them as images flowing into one another like a film might and this flickering intensity characterises his poems – “cinematic currents grabbing me up, getting me there” as he wrote in his memoir. Writing may well be “hard work” as Deeley once said in a 2016 interview, but his thrill in finding the right words – that “feels as if its caught what I wanted to say and brought a certain magic to it” – can be celebrated by the reader of this collection. “The First Orange”– another supple poem that starts with an evocation of what a boy might experience eating an orange, segues into the denial of the experience – the pocketing of the uneaten orange – and ends with the hostage, Brian Keenan, contemplating a bowl of oranges while incarcerated and experiencing a “blaze of love” – neatly encapsulates both Deeley’s invitation to the reader and his own delight in saving, if not re-living, an experience: “All yours, yours alone, so eat it. But first / eye it, smell it, mould it in your palm, / a solid yet pliable warmth.”. Deeley is skilled enough to make those oranges taste and smell as real as the one’s in your fruit bowl.

In his 70s now it is inevitable that Deeley engages with the ageing process and the death that is its inescapable end. Again there is no sentimentality here, just honesty and compassion not least for his friends – what Johnston called perfectly a “blunt lyricism”. Watching someone close deteriorating is a very painful experience, especially, for a poet, when it is language that goes. In “Syntax”, there is no mawkishness: Deeley recognises that “Life is little, getting littler, a bare headspace / the last place you will be left with, // core remnant of a collapsed star”; that final image pitch perfect in communicating the affectionate regard in which the subject was held.

“The Sundowning” is an elegiac poem about the death of a friend who seems to have shared a love of the natural world; a poem where Deeley accepts that though ‘we cry against the fates’ little will alter, will “turn back the elementals, their appetites”. It’s possible that an upbringing on a farm gives a phlegmatic approach to life and death. Certainly Deeley is grounded even when it is his mortality that is to the fore – hit by a motorcycle and flung skywards he recalls a lark ascending but concludes, “But falling, not flight, / is my forte. Into the broth of life / as a swamp, a stream, a sea coldly stirring” and out of this, like all his experiences, he will emerge to make poetry, his snail fossil “held // to amplify the resonance of the world in my ear”(“Falling”).

There is a plain honesty to this collection. Deeley seems content to mine the past – which exerts “…a pull, / the way news of latter-day atrocities will, / this nibble of unease or helplessness under our ribs”(“Hansheen’s Garden”) – while sanguine that all things will pass and poetry can encompass anything that can be observed, celebrated and accepted. His touching valedictory to David Marcus, the editor who first published Deeley in 1978 and who died in 2009, manages to communicate deep affection while recounting an anecdote about foot-operated dustbins. There is no pomposity nor pomp in this collection. Deeley recognises that whatever gains us recognition in this world, “this business of being nobodies / overtakes us” and “firm friends and faithful lovers found to be // insubstantial”(“Nobodies”). In this collection Deeley seems broadly content, grounded and reconciled to being “party to the lovely mess / of living”, lifted rather than floored by storms. (“The Absence”). A place of content that is hard-won – a sheltered wild cat that was here then disappears prompts “hallucinatons” of mother, father, “one or other // of my dead friends”. No lachrymosity, simply recognition “…that I am one // more figment of the imagination // of the earth”(“Acceptance”), which , one imagines, is fine with him.

To the end Deeley has been sustained by his relationship to the natural world he has been part of and been observing closely. The final poem, “Words”, finds Deeley in “library quiet” but surrounded by “concrete bedlam”. Shock jocks, housing crises and another mass shooting might bring down even the most robust of poets but Deeley offers us the counter of a woodland stroll, “the fresh, merciless / beauty of Spring breaking cover…” There is quiet valediction and satisfaction here too as Deeley offers up the words that come “makeshifts / of a life, to the shades / which grow more recognisable / as you edge towards them, / disappear into them, silent, smiling” (“Words”).

In one of his final conversations Deeley recalls in his memoir that his father, a woodworker and hurley maker, asked about the nature of poetry and saw it as like the shaping of timber in order “To find what’s hiding underneath and bring it out with a good smart finish on it”. There could be no better summary of the essence of this fine and highly recommended collection.

Patrick Lodge is an Irish citizen with family roots in Wales.. His work has been published, anthologised and translated in several countries and has read, by invitation, at poetry festivals across Europe. Patrick has been successful in several international poetry competitions. He reviews for several poetry magazines and has judged international poetry competitions. Three collections, An Anniversary of Flight, Shenanigans and Remarkable Occurrences were published by Valley Press, UK. His fourth collection, entitled There You Are, is due for publication in 2025.

*****

What the Earth Seemed to Say: New & Selected Poems by Marie Howe. £14.99. Bloodaxe. ISBN: 9781780377247. Reviewed by Ian Pople

There is a remarkable evenness of tone in the American poet, Marie Howe’s, What the Earth Seemed to Say, which is Howe’s first book in the UK but her fifth overall. Remarkably, Howe’s first two books were published in the same year, 1998, which might suggest that her US publisher knew a good thing when they saw it. The overall tone, which we be discussed more below, is rather unadorned, rather plain; there are adjectives but they are used sparingly. And Howe’s style is to use longer run-on sentences to convey narrative through the poems. That is not to say that Howe is necessarily a narrative poet, although there are what are clearly monologues and depictions of events in the book. It is just that there few poems which focus directly on the natural world. And where there are such poems, it is clear that Howe’s preoccupation is with, as the title of her second book states, What the Living Do. This latter book is described in the inside blurb as ‘in many ways an elegy for Marie Howe’s brother John, who died from AIDS in 1989’. And Howe has co-edited an anthology, In the Company of my Solitude: American Writing from the AIDS Pandemic.

Although it is clear that the title of What the Living Do alludes to those who are left after the dying, it has the ‘advantage’, if I may put it that way, of allowing lives in general to be part of that ‘do[ing]’. Poems from that volume included in this Selected describe, for example, the activities of young boys and girls, often quite explicit activities. And the inside blurb comments that Howe worked as a reporter and a teacher before taking her MFA from Columbia. The poems in the book are not ‘reportage’, but as I’ve suggested above Howe’s general inclination is to present activities and behaviours. It might be speculated that the poems around the death of her brother presented Howe with the technical need to avoid emotion and rhetoric, so that the reader gains the emotional resonances from the ‘events’ the poems offer. Overall, however, there is a slightly unremitting tone to the writing that accompanies a wide range of topics from those very powerful poems about the death of her brother, to the newer very loving poems about her adopted daughter, through to very interesting monologues in the voices of both Mary the mother of Christ, and Mary Magdalene.

And Howe writes with an explicitly Christian identity. That, too, might be indicated by the title of that first book, The Good Thief, alluding to the two thieves who were crucified with Christ. That identity is confirmed by the first of the poems from that book collected here, ‘Part of Eve’s Discussion’. This poem is a very powerful evocation of how it might have felt to have been expelled from the Garden of Eden. It begins, ‘It was like the moment when a bird decides not to eat from your hand, and flies,’ moves through ‘very much like the moment, driving on bad ice, when it occurs to you / your car could spin, just before it slowly begins to spin,’ and ends, ‘it was just like that, and after that, it was still like that, only / all the time.’ Here, Howe’s customary plainness is linked to a real drive (pun intended) towards that ending where the emotion both reaches and is held. Had a reader chanced upon this as the first poem of a debut volume, then that reader would have thought that they were in the presence of a poet of real potential.

From that volume too, and the last from that book reprinted here is, ‘Encounter,’ of which these are the first six lines:

First, the little cuts, then the bigger ones,

the biggest, the burns. This is what God did

when he wanted to love you.

She didn’t expect to meet him on the stairway

no one used but she did, because she was

afraid of the elevator, the locked room.

It is feels almost certain that the third person here is actually Howe herself. The first verse plunges us into an encounter with the immanent God, an encounter that is immediately both physical and metaphysical. Howe’s skill is then to move that immanence into a far more common and identifiable experience; that of the wariness of elevators. In one way, of course, the pain indicated in the first verse is reproduced in the second. But that second verse moves the singularity of the danger in the first verse into something both more diffuse, but more human in the second verse.

It is in this kind of writing, that Howe’s unadorned style pays dividends. Howe’s gifts with narrative, with a kind of reportage, if you like, means that the psychological narrative comes across more clearly. There is also a feminist feel to much of this writing. That feminism can emerges from certain roles that Howe, herself, plays as sister, lover and mother. Here, Howe is both the one who experiences but also the one who conveys that experience, sometimes with that third person aspect that we have just seen. Elsewhere, in her third person narratives of Mary, the Mother of Christ, or as Mary Magdalene, these women become emblematic of the experiences of women as a whole. This is the whole of the delightfully ironic ‘Magdalene at the Theopoetics Conference’:

Yes, the scholar said, but why ask your students

to write these close observations?

What use is it to notice the rusted drainpipe?

The young woman asleep in the library

her head resting on her folded arms?

Why should they look inside the petals of the pink tulip

to the yell pollen-coated stamen?

Or under their beds to where the dust has collected?

Don’t you want them to seek the divine?

There is, of course, a sense that this is a easy target, but for many, it is a target worth aiming at. Particularly, when that poem is followed a page later by, ‘Magdalene Afterwards,’

beginning, ‘Remember the woman in the blue burka forced to kneel in the stadium/then shot in the head? That was me. / I was the woman who secretly filmed it’. Mary Magdalene is sometimes a figure of considerable ambivalence in Christian iconography and thought, as anyone who has seen Barbara Hershey’s portrayal of her in Scorsese’s film of The Last Temptation of Christ can attest. In ‘Magdalene Afterwards,’ Marie Howe turns the Magdalene into a figure who is an avatar for the huge range of suffering meted out to women both through the ages and, especially, our contemporary world. It is the Magdalene, however, who at the end of this poem, is the one who fully realises the Christian message:

I want to see through the red bricks of the building across the street,

into something else.

Often, I’m lonely.

Sometimes a joy pours through me so immense.

The line ends with a full stop and yet is syntactically incomplete; we want a ‘so immense that…’ with some sense of a feeling. This is the final poem in the book so the reader is left with that immense and uncompleted joy.

Ian Pople‘s Spillway: New and Selected Poems is published by Carcanet.

*****

Notes of a Phantom Woman by Iana Boukova, trans. John O’Kane and Ekaterina Petrova. $20.00. ISBN: 9781946433008.

Hopscotch by Fatemeh Shams, trans. Armen Davoudian., $14.00. Ugly Ducking Press. ISBN: 9783910237032. Both reviewed by Ian Pople

Both of these poets have already achieved some distinction in their own countries. Iana Boukova received the National Award for most outstanding book of Bulgarian poetry for Notes of a Phantom Woman. She lives between Sofia and Athens and is an editor on the Greek poetry magazine FRMK. Boukova also has a novel, Traveling in the Direction of the Shadow forthcoming from New York Review Books. Fatemeh Shams has already appeared in translations by the noted British poet and translator, Dick Davis. Shams has a DPhil from Oxford, which was published as an academic monograph entitled A Revolution in Rhyme: Poetic Co-option Under the Islamic Republic which, as the title suggests, looks at the relationship between power, society and literature. Shams has also taught at a number of prestigious institutions including Oxford, the Courtauld and SOAS and is, currently, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania. Shams is also an anti-hijab activist who is exiled from her native Iran.

At first blush, Boukova’s poems nod towards that tradition of surrealism which has been part of Greek poetry since the start of the 20th century. And it may be the translations, but the slightly clipped quality of the writing does rather enhance the, sometimes abrupt, transitions between images and ideas. This is the first stanza of the first poem, ‘In Nature’:

Opinions do not concur

about what is meant by “in nature.”

Board game of the gods and fiddlesticks.

(Behind our back

trees massacre each other in slow motion.)

It is possible that in the translation, the original lyricism of the lines has been lost. But what we have here is a stark set of statements. The first is almost a parody of itself; in stating that ‘Opinions do not concur,’ we have an opinion stated quite baldly as a fact. The third line is a phrase with no verb creating an assertion which, again, the reader is not quite in the position to refute. In those final two lines, we have a complete sentence again, but it is collusive. That ‘our’ establishes a connection to the reader that we do not assent to. In those first two lines, Boukova does offer us a kind of prospectus for the poem that follows. And so, the idea of nature as a board game and as self-destructive are part of the scope of the poem. That sense of nature as a kind of threat moves through the poem in a way that is clearly ironised, and we surface in the penultimate stanza with:

The city is always preferable.

Here no animal bites.

Wouldn’t it be fantastic

if there were a pill you could take

and all these sadistic, infinite things

would take on the color blue?

In these concluding notes, the clipped quality of the writing underlines the emphatic comments. Those comments too, are strengthened by the adverbs, ‘always,’ and ‘here.’ And the longer, conditional sentence at the end, pushes its way through to the words, ‘sadistic,’ and ‘infinite,’ and then that rather strange ending. This is an ending that implies the diminution of the threat of nature, without actually showing how that diminution might work.

The final stanza comments:

But we don’t buy all that. We wear shoes,

we take walks in nature.

We only see the nearby darkness.

That collusive ‘we’ is back here in force. The simple present verbs again emphasis the certainties that Boukova appears to be sending up. But we are left on a note of intriguing ambiguity. We see that the darkness is nearby but we don’t see a darkness beyond that; nature’s primordial darkness, perhaps. And we ‘only’ see the darkness, we don’t see the light in nature, we take our shoes and take our walks but we don’t really see what is going on; goings on that would puncture our over simplified view of nature as ‘dark.’

Notes of the Phantom Woman does not have a contents page; however, the contents are broken into five sections divided by black pages where the section title is printed in white. The first section, ‘Urban Myths or My Favorite Artist works with Gravity,’ contains individual poems of which the poem ‘In Nature,’ quoted above is one. The next four sections, ‘Tractatus’, ‘Don’t Panic. It’s a Thought Experiment’, ‘Umwelt’, and ‘Black Haiku,’ are all longer poems broken into sections. The section called, ‘Tractatus,’ is clearly a nod to Wittgenstein. Its, generally, short sections begin with a statement inside obliques, such as this which begins the sequence, ‘/I think it is hight time / that I clarify my position regarding pigeons./’ The sequence returns to pigeons throughout its sections in a way which possibly satirises its own obsession; although ‘obsession’ has to be the word used for comments such as, ‘There’s no other animal / that defecates in the shape of a statue,’ or ‘We’ve done something to the pigeons, / that’s for sure. / I’ve seen ugly pigeons. / I’ve never seen an ugly vulture.’ And elsewhere the rather pathological nature of the writing is reinforced by a verse paragraph such as this, ‘/Maybe I’m also prone to seeing symbols./ The mask of the ridiculous serial killer / known as Ghostface / invariably reminds me of Duchamp’s urinal.’

So, it’s interesting, perhaps, that in the sequence, ‘Umwelt,’ Boukova comments, ‘I want to find out what it is nowadays /that makes the above “readymade” poetry so suspect.’ There is little, really, that is “readymade” in Boukova’s fierce collection. A note on the translation comments that Boukova’s translator from Greek and her translator from Bulgarian worked closely with Boukova on the final translations, and that ‘the Greek and Bulgarian versions met and merged and became this English translation: a kind of third original, which feels … authentic, reflective and true to the poet’s vision.’

Fatemeh Shams’ chapbook Hopscotch is, as noted above, a small addition of Shams’ already quite extensive productions. It is produced in a collaboration between Ugly Duckling Press from Brooklyn and Falschrum from Berlin. This latter is significant as the poems are set in Berlin and, in sharp contrast to the Boukova, concentrate on elements of autobiography with the ‘I’, seemingly, very much the first person narration of the author, Shams. That narrator clearly lives in an exile that absorbs pain from not only that exile, but also from those she has left behind and the world in which she lives. In the poem, ‘Berlin,’ Shams writes, ‘Two weeks into spring my mother says: / inflation is rampant, still no mail / the officials are pocketing Eid gifts. // The VPN breaks down / so does my mother’s face.’ That is immediately followed by the narrator walking ‘in the East,’ which we are likely to interpret as the ‘old East Berlin.’ Here, Shams ‘read[s] fortunes for the ghosts wandering your wings East and West.’ Those ghosts include, ‘the Russian soldiers buried in Treptower Park / the Turkish guest workers of Kreuzberg / for the banished souls who died in Auschwitz, Treblinka. Sachsenhausen.’ In the midst of this, Shams celebrates the healing of her removed wisdom teeth. This is a poem that ends, ‘I walk in you and recite: / I wish I could drive a nail into your wall / and celebrate life in your streets / by stapling the pieces of my face together.’ So, if Boukova was fierce, then Shams can be just as fierce from a very different and much more autobiographical standpoint. In a sense, however, both these writers are more than aware of the partial victories that life creates for us. And that awareness is not something to be cast aside as some kind of Pyrrhic victory. As Shams puts it elsewhere, ‘always I start by forgetting / and arrive at poetry.’

That kind of declaration is complex and possibly enigmatic. For Shams to move from a mental act to poetry might imply that the second is more important or, simply, better. But the poem that the quotation comes from is ‘Names,’ which begins, ‘What should I name the bird that bathes in ice? / the bud that grows recklessly in February’s frosty mouth / the sun that licks its wounds at night.’ There is much in this chapbook at follows that inclination to name. The poem ‘Berlin,’ is as much about finding a name for this huge and complex city, and the process of finding a place within the city as does the poem, ‘Name.’ As a, clearly, reluctant exile, for all that she is Oxford educated and a teacher in America, Shams’ poetry is a precise, and often deeply lyrical exploration of how one is in one’s surroundings. If that exploration is uncomfortable, that discomfort lies, perhaps, between the ‘forgetting’ and the ‘poetry,’ that Shams adumbrates.

These books are by writers who live amidst a number of different cultures and who live in different languages. As such, they offer profound explorations of what it means to negotiate one’s being in the world. Ugly Duckling Press’s calm, unelaborate little books fit into a backpocket; and are lovely little vade mecums to travel with you as you travel with these very interesting writers.

Ian Pople‘s Spillway: New and Selected Poems is published by Carcanet.

Close-Up by Quentin Cowdry. £10.99. Hedgehog Press, ISBN 978-1-916830-47-9. Reviewed by Anne Symons

This beautifully produced book by former Times and Telegraph journalist Quentin Cowdry won the Hedgehog Press first pamphlet competition 2023. As the title suggests, Cowdry opens up unexpected and intimate details in the canvas of life: a wave, a tie-pin, north Norfolk, Provence, mountain pines – all revealed through a different lens.

Light, the photographer’s tool, is used skilfully in ‘Morning Refractions’ where the poet, taking a bath in London, is led to thoughts of California and Hockney’s painting Sunbather:

Bath water has guttered to a halt […]

blue and curling light trails […]

a prone man, naked,

white buttocks sunny side up

to an unreproving sky.

There is often a sense of mystery in these poems, Cowdry intrigues with half-told stories, as in ‘Faces’: ‘the adulterer’s small grimace / as he administers a kiss / to his wife’s forehead’. Or the chilling hint of abuse in ‘Tie Pin’: ‘gripping a boy tight, his tie pin’s pearl / smooth and cold against the pupil’s cheek.’

Throughout these poems Cowdry surprises with fresh imagery: ‘a bluster of dads’, ‘towers on steroids’, snarling white vans’, ‘willows thrashing like cheerleaders’ pompoms. In ‘Threshold’, a poignant evocation of fatherhood, he describes how:

Soon the final wisps of childhood will go,

soon the final teddy. Before long that habit

of sucking the glass’s rim as if you’re

still seeking the beaker’s ease will just

be a blushful memory.

There is a subtle use of rhyme and half rhyme, as in the poem ‘North Norfolk’, an evocation of place:

[…] take the pilgrim path to Holkham Beach.

There they’ll nest on sand and shell and find

a sort of death. One step off the boardwalk

that leads across a fringe of pine

Cowdry uses a range of form; free verse, quatrains, tercets, allowing the poems to breathe their shape onto the page. In: ‘There’s Nothing Good Or Bad’ words, lines, stanzas spread disjointed across the white space reflecting a fractured relationship: ‘as Hamlet said good bad / it’s all a matter of how you think’

In the beautifully titled elegy: ‘Making Peace With Landeg’ the casual opening: ‘It wasn’t the main point of the call’ takes us through the poet’s regret and insight as he reappraises his relationship with the deceased:

[…] we punched low

and mocked out tutor’s presumed

joylessness, the bandana of gloom.

Eight months later, on a call with a friend,

I learnt that you were dead.

Only then did I start to read your work;

only then, through lines as sharp as surgery,

discovered the whole man – vital, confessed,

the vocal heart beneath its screen of bone.

This is honest, clear-sighted writing. Life is shown in all its subtlety, humour and pain. Read and re-read these poems, Close-Up deserves a place on your book shelf.

Anne Symons began writing poetry in retirement after a career teaching deaf children and adults . Her work has appeared in a range of poetry publications, including Agenda, Dreamcatcher, Ekphrastic Review, Ink Sweat & Tears, Orbis, Poetry Salzburg Review, Steel Jackdaw, The High Window and The Atlanta Review. Anne has completed an MA in Writing Poetry at Newcastle University and the Poetry School in London. Her pamphlet Shifting Sands was published by Littoral Press in 2024.

*****

The Chain Bridge by John McKeown. £10.00. Caparison. ISBN:978-1-0687475-2-6. Reviewed by Kathleen McPhilemy

This is not a cheerful book. Yet the almost unrelieved gloom in John McKeown’s new collection, caused not so much by the currently dire state of the world as by a rather old-fashioned existential angst, becomes strangely addictive. It takes us into a solipsistic universe of hard-pushed metaphors and philosophic quandaries where the only inhabitant is a reconstituted version of the poète maudit.

There are some moments of delight and beauty. McKeown has an eye for nature and the changing seasons. Single lines and phrases attest to his close observation of detail: ‘The wood pigeon persists / A sonar pulse somewhere in the trees’, ‘the laconic / Needle tweet of birds’, ‘The chestnut leaves have streaks of rust.’ He is also good on streetscapes: ‘I love the tall century-shrugging houses / Freshly painted, flaking’; ‘century-shrugging’ ,a compound which defies analysis, is very effective. ‘The Nature of Things’ presents a street scene with ‘overcast sky, the pastel houses, the day muted’ disrupted by workmen in ‘searing orange’ before veering off into a discussion of mutability and then returning violently but probably figuratively to the workmen:

I grab the workman’s hammer, pushing him aside,

And ram it in the threads of the digger.

Typical of McKeown’s practice is the choice of a concrete detail which acts as a springboard for a dive into often self-reflective rumination or pathetic fallacy:

Empty paths, lined with leafless contorted apple trees

Smeared with pale green lichen

In the cold clogging grip of some ageless unanswerable question.

‘Uphill’

The poet does not hold back on his feelings of misanthropy: ‘Always something fresh to hate’ he begins in ‘Freshet’, going on to rage against the ugliness created by ‘generic oafs’ who he is ready to string up with electrified barbed wire. This dislike of other human beings is also evident in ‘Two Legs Bad’ where he inveighs against ‘the whole baseball-hatted world’. This may be an attack on the crass behaviour of the likes of Trump supporters, but when the writer privileges himself over the rest of humanity because of his ability to appreciate ‘fine tiny blades / Of flowering weed, growing between / The cobblestones’ gaps’, an uncomfortable whiff of elitism mingles with the misanthropy. There is zero empathy in McKeown’s work, and this applies even to what might be described as the love poems: ‘In the dark let me slip my hand within you / And find, and feel the texture of our difference’. This is more Charles III than John Donne, while his poem to a plant he seems to have acquired in lockdown is positively creepy: ‘something as small as a glass of water / Gets her so quickly, darkly moist’. None of the lovers we encounter seem real, but this hardly matters because what the poet has invited us into is a solipsistic virtual world where other people are shadows on the screen where his drama plays out. He seems to explore such notions in ‘Solar Plexus’:

But the world boxes clever.

Is sometimes shadow, sometimes substance,

The fight depends on a flipped coin.

The poem ends, ‘The world runs rings around me. // Though I am its sun.’ The title and the last line drove me back to the etymology of solipsism, (Latin ‘solus’ + ‘ipse’) and the possibility of a pun on ‘sol’ and ‘solus’. Because the poems are the work of a mind alone in a world of shadows, predictably they are engaged in self-reflection and the poet’s agon. Sometimes this is with alcohol: ‘Hung Under’ is a wry account of the reasons for and the battle to resist the next drink. ‘Running on Empty’ is self-aware and darkly comic. In ‘Days of 21’ there is a note of hopelessness and self-reproach;

Before or, if I’m feeling strong, after

A shop-bought dinner I succumb

And succumb some more until midnight dawns.

Then drag out a last glass or two

Along the road that leads inexorably

To the lightless one.

The collection is pervaded by the process of aging and awareness of impending death, realities which the espousal of solipsism cannot avert, ‘I see the sands are running out / I see them dragging my features / Increasingly unsubtly out of place’ (‘Ghost’), ‘Bumpier, veinier hands, thinner greying hair’ (‘Coughing Up’). This last poem reveals another stylistic trait which stems from McKeown’s unrelenting introspection. The rather gruesome pun of the title leads into an extended metaphor based on the idea of credit. He treats the metaphor as if it could do the work of an analogical argument which leads to forced puns, ‘drain me into banks of air’ and some awkwardness in following through to the final stanza. Nevertheless, although the sentiment that the poet will never enjoy what he has paid for in advance is characteristically gloomy, the last line is magnificent and in its extended length, somehow uplifting: ‘Autumn burning down the town, the way swallows swoop and dive and fall.’

The final two poems also strike a more upbeat note. Apparently, the poems in the collection were selected by the editor, Alan Morrison, so we cannot know if this was his choice or McKeown’s. In ‘Downhill’, the poet comes close to celebration, ‘”It’s all downhill from here” ‘… ‘But the moment was rich and others were richer still. / And, at least, we were on the hill.’ The last poem, unusually, is descriptive, allowing what is seen to speak for itself rather than developing into argument or comment. It conveys a sense of resolution and acceptance which is both surprising and appropriate in a book full of restlessness and rancour.

CROAK

xxxxxxHesitant crow call

A broken ratchet

The day’s emptiness spreading

In every direction.

A day of the world only

For there are chinks of soft blue light

Through the loose-knit ribbing of cumuli

And the bare trees are conductors, still;

Gathering this winter

Caesura, tight

Around each leafless twig.

Kathleen McPhilemy grew up in Belfast but now lives in Oxford. She has published four collections of poetry, the most recent being Back Country, Littoral Press, 2022. She also hosts a poetry podcast magazine, Poetry Worth Hearing.

****

Bar de Las Reminiscencias by Isabel Bermudez. ISBN: 978-1-3999-8385-3. Reviewed by Kathleen McPhilemy

The title of the third section of this collection is ‘Dear Life’ a phrase which seems to sum up the view of life as precious and precarious which runs through the poems. As one might expect from someone who is an embroiderer and textile artist, this book is exquisitely produced on high quality paper with delightful drawings by Simon Turvey.

Bermudez was born in Bogatá and returned to Colombia at the age of thirty to work for several years in documentary television. Most of the poems in the eponymous first section, ‘Bar de las Reminiscencias’ are set in Colombia, whilst the second section explores the history of different parts of England and the third ranges more widely geographically and thematically.

In the first poem, the speaker awakes from sedation or a coma, to find herself ‘in Anita’s house’ who, from other poems, seems to be her host or a close friend or relative. We never find out what has happened, but we know we are in Colombia: ‘”What day is it?” / “Domingo”, she said.’ ‘Lamp’ indicates the welcoming nature of Anita’s house, ‘ a desk lamp / shines in the window’ while the next poem is a portrait of a woman who is probably a servant in the house, the hardship of whose life is presented very effectively through her metonymic white cardigan:

the wool of the cardigan

had puckered at the shoulder,

left a ghostly outline

of the wooden ears

just above the top rail

of the hard chair

she hung her life on.

The presence of the poor and the abuses of Colombian society, from the exploitations of the workers who panned for gold to the violence and corruption brought in by the drug cartels create a dark undertone for many of these poems where beauty and everyday detail coexist with terror. Poems on two facing pages, ‘Armenia’ and ‘The flowering trees’ refer almost incidentally to the gold and the cocaine as they address apparently harmless topics such as eating trout, or flowering trees. However, the repetition of redness through both poems creates a sense of menace and danger: ‘the scarlet was still dripping’, (‘Armenia’), ‘a wilting and falling of blooms / swept away, blood /on street-cleaners’ brooms’. (‘The flowering trees’). So when this second poem ends with ‘flowers / that keep dropping / and piling / and littering the roads’ we know the reference is not only to flowers. Thus, we are prepared for the final and title poem in this section, surely a dedication, which shocks us in its sudden swerve into violence:

the one who, next day,

mowed down with a dozen others –

never showed for work –

for him as much as another

this fistful.

The concern for ordinary, unrecorded lives – ‘In the parish register / their names are dust’ – persists in the second section where poems are set in different, mostly rural, areas of England. ‘Lost’ commemorates the ‘one in every five’ of Devon men who were forced by economic necessity to go to sea. ‘Hung’, superficially a poem about pheasants, laments ‘the red stain’ of men hanged for poaching and lost to their ‘distant, / distant cottage.’ The poet’s pared-down, strongly visual lines, her use of colour and telling detail powerfully convey injustice and suffering. ‘Breughel’s geese’ is a wonderful poem, although I am uncertain why the geese are Breughel’s and those in the facing drawing are certainly Canada geese. The poem suggests that the geese who ‘circle in to land, feed, preen’ , a description typically economic and precise, are, or represent the spirits of different trade and craft workers from the past. The arrival of the geese evokes the past, ‘the far-off clatter of mil cans / the wheezing of bellows; // a clip-clop / of horseshoes on cobblestones.’

They hustle and flap

blacksmiths, welders, carpenters

all about their business

small as us.

We feel that the poet is on the side of the small people and recognises her kinship with the bygone artisans. In ‘Journeyman’ which is the title poem for this section, the poet again depicts the struggles of the poor, this time those who did not go to sea, but ‘roamed the country’ seeking work and when ‘their trade could not save them’ had to beg or steal. However, these poems are not only about misery; as in the first section, there is relish in the beautiful, especially when it is unexpected. ‘At harvest time’ describes the harvest of onions, and the beauty of their shed skins after the machine has pulled them up:

They speckle the open field.

Risen moons;

Food for the flies and the crows.

August leavings. Winter gold.

Or, in another poem about journeymen, the poet suggests the lure of the open road which ‘beckoned them, always beckons, / glinting like ditchwater / in sullen sun.’ This amazing image manages to encapsulate the transformation of the ordinary to convey simultaneously threat and promise.

I could wish, in a book as sumptuously produced as this one, that each poem had been allowed a separate page. ‘At Norman Cross’, a very powerful poem, loses out by following so immediately after the previous piece. This parsimony with space occurs more frequently in the final section of the collection and, even where poems may be thematically linked, I feel they deserved more room. This final section is much more varied, ranging through history and geography. The strong sense of the past is often more personal and there are references to death, whether that of the poet or others. There are also moments of epiphany, like the description of the wren ‘taking his dust-bath’ or ‘that flash’ of the egret, ‘the moment / everything changed / and there was suddenly / before and after’. In the title poem of this section, ‘Dear Life’ the poet returns to South America and Colombia, a ‘pais de horrores’, to reassert the underlying message of the collection, that life is:

marvellous and terrible,

all of it.

Kathleen McPhilemy grew up in Belfast but now lives in Oxford. She has published four collections of poetry, the most recent being Back Country, Littoral Press, 2022. She also hosts a poetry podcast magazine, Poetry Worth Hearing.

*****

First, I Turn Off the Light by Katy Mack. £8.99. Broken Sleep Books. ISBN:978-1-916938-21-2. Reviewed by Hilary Hares

As the opening quotation points out: ‘we are all haunted houses’ (H.D.) Whilst this may be true, what haunts us often remains internal and unexplored. First, I turn Off the Light opens this door, however, and takes us into the little known world of OCD (Obsessive Compulsive Disorder).

Whilst a psychiatrist will categorise this condition as uncontrollable recurring thoughts, it takes a poet to draw us in so deeply to these experiences that we begin to believe they could almost be our own. These feeling are powerfully realised in Katy Mack’s debut collection and the result is both unsettling and compelling. In the opening poem: ‘What I Haven’t Said Is’ we learn that: ‘… the walls which keep us safe / are getting thin.’ The pressure of something other which is always waiting in the wings is apparent from the outset.

We quickly become fascinated by the poet’s world which, at times, transforms day-to-day life into a macabre circus where: ‘The Clown Upstairs’ appears in random places and at various times of day:

Other nights he is so quiet I begin to think

he has gone away entirely,

until the morning

when the soured lemonade of his breath

crouches in the corridor …

In addition to orchestrating these bizarre mindscapes, it seems that OCD also rules with an element of coercive control: ‘When the scarecrows come, you must not question why’.

These feelings of entrapment are mirrored in a short sequence about Emily Bronte, the lesser known sister who died young. Emily is clearly another of the poet’s preoccupations and one of the few surviving scraps of her writing simply says: ‘I can’t get out’, a feeling it is easy to imagine the poet shares.

Although OCD is clearly isolating, however, this is not a journey the poet is taking alone, in: ‘Some Nights’ we’re moved by the tender description of support from the poet’s partner:

Some nights you place your hand on my spine and count each vertebra

like gold coins, like you know the cost of things and I am terribly dear.

Despite this, it is clear that the relentless nature of the thoughts is both exhausting and debilitating and: ‘My Big Night Out’ is a good example of the duality at war in the writer’s mind:

so I’m going to drag myself

out for the nightxxxxget pig-drunk at the barxxxxsteal the fattest chip

fromxxxmy own platexxxwhen my back is turned.

The all-encompassing nature of the condition is further revealed in: ‘The Woman in the Mirror’ where the reflection reveals: ‘her face so like my own / only aged in the antique glass.’ Initially it manifests as a positive presence ‘I found her disregard / for my usual routines refreshing.’ As the poem unfolds, however, its actions become more and more extreme until: ‘I wanted to wipe her away, as you might a dirty mark’.

In conclusion, whilst these remarkable poems deal with a complex and crippling condition, they are written with a light touch and convey their story in manner which is both lyrical and compelling. We are enveloped into a strange new world where we get to walk a mile in the poet’s skin as well as her shoes. As a result, this slender volume punches well above its weight and is to be highly recommended.

Hilary Hares’ poems appear widely online and in print. She has also achieved success in various competitions. She has an MA in Poetry from Manchester Metropolitan University and her pamphlets; A Butterfly Lands on the Moon, Red Queen, and Mr Yamada Cooks Lunch for Twenty Three are available through: www.hilaryhares.com

*****

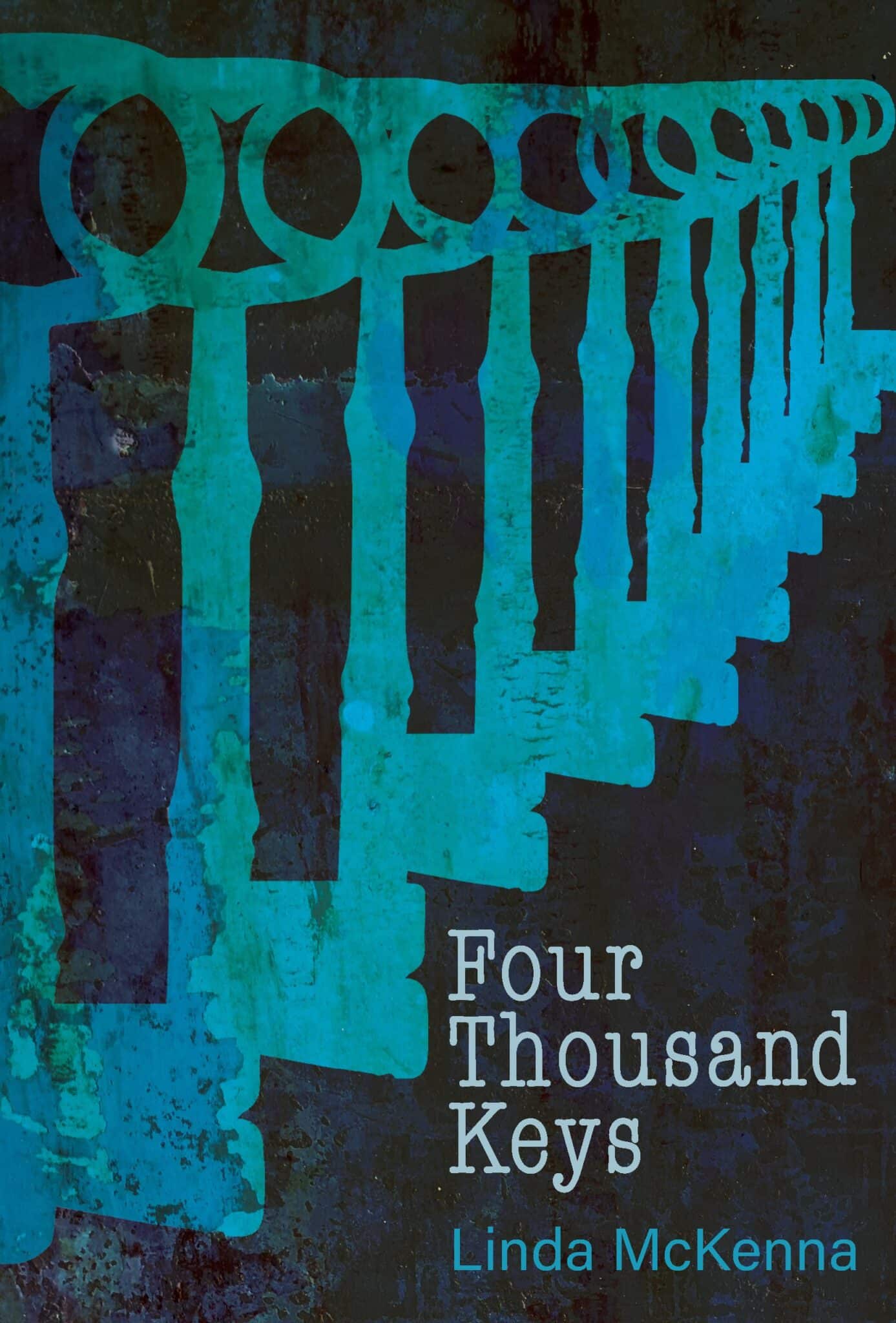

Four Thousand Keys by Linda McKenna. £14.00. Doire Press; ISBN: 978-1-915877-00-0. Reviewed by Rowena Sommerville

Four Thousand Keys is Linda McKenna’s second collection of poems, and is an interesting, allusive and rather haunting work. The collection was catalysed by the writer’s discovery of the true story of Elizabeth Dunham, who, in 1819, was arrested for stealing two keys, ‘the goods of the Governor and Company of the Bank of England’. Searches of Dunham’s premises subsequently revealed a trunk containing about four thousand keys, including keys to the Royal Exchange, the Houses of Lords and Commons, and the padlock of Greenwich Watch-House, almost all of which were labelled and dated. The ‘Proceedings of the Old Bailey’, where she came to trial, say that she was a widow who had run a boarding house, but a ‘series of villainies’ had removed her livelihood, and that unhelpful recourse to law had ‘made her opinion of men still worse’. The prisoner is quoted as having said, ‘I have come here for justice…. there has been none here for a long time’. The Jury found her Not Guilty, believing her to be insane at the time of the offence, and she was committed to Bedlam.

The poems take flight from this sad and intriguing opening story, and explore many aspects of being an ageing woman, of access and exclusion, of motherhood, of invisibility, and sometimes of the materiality of keys and metal, of fabric and writing implements. Echoes of the story and its possible interpretations occur throughout, as notions and patterns rather than with any literality.

Many of the poems are written in the first person, and/but even more than is usually so, it’s often not clear who that first person actually is – could be the poet, or Elizabeth Dunham, or someone else altogether – and that potential confusion is effective in making those poems immediate and strong in the telling, but also in making the reader have to work things out for themselves, if they can; there’s a play between immediacy and distance. In ‘Horoscopes’ the poet/narrator speaks of their aunt who seems to have worked in an asylum ‘when asylum meant safety’:

On full moon nights, the asylum in uproar,

the nurses hugged the patients tight,

chanted in their ears; you were Moses

drifting out to sea, we waded in, we saved you.

‘Fifty Miles’ opens with a quote from ‘The Bank of England and Gold’ (seemingly the title of the Bank of England Museum Video) which states that ‘an ounce of gold would stretch fifty miles’ and the poem’s narrator, perhaps the poet, follows an elderly scavenging vixen through the city as she is ‘drinking puddles/ of stars, eating crescents of lemon’. She describes the vixen ranging away from familiar territory:

………….. unravelling further

and further until she has covered

the stretch of an ounce of pure gold.

In ‘Cartography’ McKenna says she has made ‘a map for the lost’, and, remembering the processes of making an ‘antiqued’ map at school, plays with the variable meanings of maps, keys and legends, and the occasional undisputable image or fact:

……………… The key is the one

we learnt at school, a legend pitched

between childish drawings and an arcane

code. Concentric circles are slopes,

gentle or steep, dotted lines, borders;

but a windmill is a windmill.

‘The Things Themselves’ seems to return to the matter, and material nature, of actual keys, with McKenna possibly imagining some of Elizabeth Dunham’s thoughts, and without ever actually naming ‘keys’ as the poem’s subject, but that is my reading of it. The poem begins by outlining the (rather shocking) perceived comparative importance and individuality of ‘the things’:

Once they were interchangeable,

like pet cats or daughters, now,

they are fingerprints or souls,

belonging only to themselves;

The narrator says that, however, if the keys (I think) lose their purpose and importance, then they should be buried in the ground to ‘bleed their alchemy into the roots’ of sticky weeds which she would carry about with her in the ‘drooping hems and splitting/ seams of my slowly shattering gowns.’

‘My Son, Skydiving’ is a lovely poem, with different possible interpretations skilfully interwoven – it suggests, by its obvious modernity, that the poet herself is addressing a grown-up son who is undertaking parentally worrying risky activities, and has a sense of self-reproach for having allowed him to enter a world of dangers, but it might also refer to a much earlier, tragic loss of a child:

………… thought you safely cocooned

in the womb. Until under my feet, the wind

vibrated the echo of a shriek, made you leap,

turn a complete somersault in your amniotic

sac, acquainting you fatally with the lure

of acrobatics, the feather float of ghosts.

‘The Unlocking of a Hem’ brings together themes of keys, infant death (dead unbaptised babies go to Limbo), religion (through the referenced notions of Limbo and the Pope), Catholicism (the Pope unlocks Limbo to free the babies), and women’s undervalued work – in a pleasingly sharp way. She imagines the Pope searching for the appropriate key and then possibly having to use an alternative approach:

……… Or, since Limbo was the hem

of the afterlife, did a seamstress mending

the fraying embroidery on a stole or mantle,

hunt in her sewing box for a seam ripper,

show him how to unpick the tight stitches?

The final poem, ‘In Which I contemplate a Tattoo’, has the poet trying to choose a suitable design for a tattoo, listing commonly used images and encouraging phrases (presumably not chosen). She closes the poem and the collection with:

…………… only God can judge me,

and every stranger on the bus seeing

on the inside of my wrist a tiny open book.

In all the best senses, Four Thousand Keys is not an ‘open book’ – it is an allusive and layered poetry collection that requires careful attention from the reader, but it is definitely a book worth opening. Linda McKenna has taken a strange true story from the early nineteenth century, and has worked outwards, and inwards, from it, to explore themes important to her, in interesting, skilled and compelling ways. This is an attractively produced book, containing powerful poetry, I recommend it.

Rowena Sommerville is a writer and singer, and lives on top of a cliff looking out to sea in beautiful North Yorkshire. She has worked in the arts for all her life, sometimes successfully. She originally wrote and illustrated books for children, is widely published in poetry magazines, and her first adult collection – ‘Melusine’ – was published by Mudfog Poetry Press in 2021. She won a Hedgehog Press Stickleback leaflet competition in 2023 and was the Visual Artist in Residence for The High Window in 2022.

*****

Daughter of the Sun by Rachel Spence. £10.99. Emma Press. ISBN 978-1-915628-34-3. Reviewed by Pat Edwards

The sonnet sequence which forms the opening part of this book, ‘Call & Response’, is a profound series of twenty-eight poems rich in breathtaking imagery any poet would be proud of. Spanning forty-six years, the pieces draw on very particular moments and memories, full of a strange mix of the beautiful and extreme.

In the very first poem it is around midnight in July 1976 and there is ‘bewildering heat’, the kind I remember so well myself as that was the year I sat my ‘A’ levels. The people in the poem witness some owls:

Two maybe three,

their beatless wings spellbound against

earth’s pull. Ten seconds we’ll remember

all our lives.

What a way to set up the sonnets that follow, the next jumping to 1986 and then to 2005 and so on.

Six weeks after he left me

and you’re the one who’s grieving.

The poems plunge us into the chaos of life, the clear tensions between mother and daughter, the almost inevitability of illness. The fourteen-line form maintains a rhythm throughout but there is no strict adherence to sonnet ‘rules’. Rather the poet revels in the discipline that the form provides, forcing her to keep her references punchy and tight. Spence delivers such a range of events, so many emotions, all packed into carefully measured phrases. She changes dressings, gets two years’ grace from illness, enjoys sun-filled days, faces hospital, operations, and eventually the refusal of her mother of any further treatment. The poet watches as days drift by, until the very last, capturing every feeling with extraordinary poignancy and care.

To finish the sequence, the poems take us to the river and to the balm of swimming and to an appreciation of nature. The poet uses words unfamiliar to me but explained in notes at the back of the book. Words such as spannel, swale and thermocline, which help us understand different characteristics of water – calm, turbulence, fluctuations in temperature.

I think this is one of the most captivating depictions of a mother daughter relationship I have ever encountered. Although bursting with emotion, it is at the same time measured and self-contained. Hidden in the sequence, the ‘I’m done, Mum, really done’, the ‘What haven’t you told me’, the ‘I’m proud to be your daughter’ all find their voice. Even ‘You will take your fucking tablets!’ has its place, as does ‘I am a good daughter’, and the oh so tender ‘last night you came to me as rain,/your heartbeat tapping on the gutter.’

Some eighteen months after the mother’s passing, the poet admits ‘we’re closer than we’ve ever been’ as she endures ‘the fury of deep time.’

The second part of this book is ‘Medea’s Song’, Medea being the woman who married Jason and helped him search for the Golden Fleece. In Euripides’ plays she kills their children – shocking – so the reader wonders where these poems will take us. The first page, this work is a continuous sequence with no individual titles, suggests that Medea’s fate is to be ‘unmapped,/unread, unnumbered’, so perhaps the poet is here to put that right.

In this interpretation of Medea’s story, ‘she loved the sea’. Medea is taught science, learns about stars, time, planets, but her understanding of emotional matters such as love seems more of an enigma. Did she love her father, it seems so; and nature, certainly. But did she have children, love them, kill them?

Medea consigned

to history’s portacabin

for all maternity!

Perhaps the myth depicting a murderous mother goes too far. Spence offers us alternatives and strives to defend the childless academic woman, celebrate the value of this female lifestyle choice, proves wife and mother are not the only labels worthy of championing.

Spence is a poet unafraid of the big themes and embarks upon them with a real command of language. I surprised myself with just how much this style of writing appealed to me, the clever use of the sonnet series, the re-writing and up-dating of Greek mythology, both handled expertly. This book has great depth and is a refreshing take on feminist themes in the hands of a writer with superlative skill and empathy.

Pat Edwards is a writer, reviewer and workshop leader from mid Wales. She hosts Verbatim open mic nights and curates Welshpool Poetry Festival. Pat’s work has appeared in anthologies and magazines and she has three pamphlets: Only Blood (Yaffle), Kissing in the Dark (Indigo Dreams), Hail Marys (Infinity UK).

*****

The Twice-Turned Earth by Siegried Baber £7.50 Poetry Salzburg ISBN: 9783901993855. Reviewed by J.S. Watts

This is the first time I’ve consciously read any poems by Siegfried Baber. Based on this pamphlet, I shall be seeking out more of them. According to the back cover blurb, The Twice-Turned Earth is Baber’s second pamphlet. It’s a publication of thirty-two pages and twenty-five poems contemplating the landscape of memory and the memories embedded in landscapes: poems that explore the UK’s countryside both literally and metaphysically.

Most of the geographical landscapes explored are rural, although the opening poem, Gökotta, uses a domestic setting: ‘and the distant disturbance of traffic on the bypass’ to explore the landscape of language and things that cannot easily be said. While the second poem, London Road West, has a distinctly urban setting:

… Yesterday someone

painted the postboxes pink as

a protest against spectacular diseases.

Behind our reflection two men

dump a sofa on the pavement

outside a funeral directors. Lights jump

from green to red.

The majority of poems, though, have a rustic, or at least a green, backdrop. Some relate to specific, named and real locations: Selborne, Avebury, Birdlip, Cefn Hill, Cooper’s Hill, Watersmeet and West Bay. The landscapes of other poems are less geographically precise, but equally rural.

Similarly, some of the incidents or memories explored may, or may not, be factual and personal to the poet. Some clearly relate to events beyond Baber’s lifespan. Others could be either, forming part of a blurred temporal landscape that blends with the swathe of physical geography laid out before us and described in insightful detail within the poems.

I was particularly taken with the poem Memento Mori, which strikingly describes the aftermath of the demise of the Selborne yew tree in Hampshire in terms of the Crucifixion:

…pilgrims

and druids and day-tripping drop-outs

came for whatever small scraps

remained: a well-preserved lance of wood,

seven berries, the stamen’s yellow

and toxic shroud.

As I have often found to be the case in well-constructed collections, there is tonal variety between the poems. Some poems are upbeat, some are sad, but I found the tone of the pamphlet, when taken as a whole, to be decidedly elegiac – a lament for past times, or current times that will fade into the haze of the past, never to be repeated except as memories:

… a strange

collectible grief; a keepsake taken down

from the attic and scrutinised for signs

of wear and tear, for loss of value

from the poem Matthew, remembering a dead childhood friend, or perhaps, even more tellingly, from the poem Map Ref. 51°18’48″N 002°22’54″W:

and the dust from that day

still shimmering when it settles unseen

over those blank distances

between what was

and all that might have been.

These well-crafted poems form a slim, but rich publication of a depth to support multiple, rewarding re-readings.

J.S. Watts is a poet and novelist. Her poetry, short stories and non-fiction appear in diverse publications in Britain and abroad and have been broadcast on BBC and independent radio. Her published books include: Cats and Other Myths, Songs of Steelyard Sue, Years Ago You Coloured Me, The Submerged Sea, Underword (poetry) and A Darker Moon, Witchlight, Old Light and Elderlight (novels). For more information, see her website https://www.jswatts.co.uk/