*****

A Bird called Elaeus: poems for here and now from The Greek Anthology, translated and arranged by David Constantine • Philip Gross: The Shores of Vaikus • Claire Dyer: The Adjustments • Rachel Carney: Octopus Mind • Marin Bodakov: The Chaos of Desire • Nia Broomhall: Backalong

*****

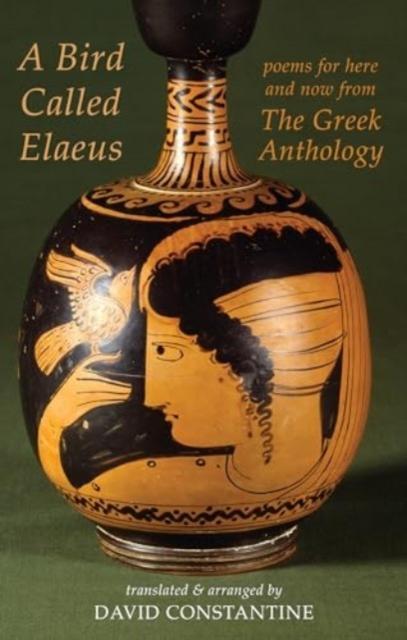

A Bird called Elaeus: poems for here and now from The Greek Anthology, translated and arranged by David Constantine. Bloodaxe Books, £12. Reviewed by Merrym Williams

The Greek Anthology is a collection of some 4500 epitaphs and short poems from the ancient world, written over 1500 years by about 300 authors. Of these, the best known is Sappho, but there are also semi-familiar names, like Meleager or the prolific Leonidas of Tarentum. David Constantine has translated and arranged a few hundred for the benefit of those who know the Greek myths, but not the Greek language. He says he wouldn’t actually pass GCSE in that subject, but as he is a splendid poet, it hardly matters.

Most poems are only four to eight lines long, sometimes shorter. Too often they are about grief, like this by one of the few women in the anthology, Anyte of Tegea:

Beloved and unwedded child of mine

Leaving me childless so we shall remain.

I visit a likeness of you made of stone

And speak what cannot be and might have been.

Or this by a bereaved father, (Diodorus or Zonas of Sardis):

Dour ferryman, coming for the child Euphorion

When you hush your prow through the reeds and touch the shore

Be kind. His father, standing in the muddy shallows

Will hand him up the plank. Reach down, Charon

Bring him carefully on board. Those are his first sandals

His pride and joy. But his footing in them is still unsure.

The Greeks were not so very different from ourselves. They experienced pain and loss, perhaps more often than we do; they took for granted that gods existed and were anxious for their favour. They dedicated their most precious objects, the tools of their trades, to their gods; Antipater describes three friends – a musician, an archer and a hunter – offering their lyre, bow and net to Apollo because all long ‘to excel in what they do’. Another poem I liked is about a woman who gave birth underground after an earthquake, and survived. ‘Just one such outcome proves the gods are kind’ – (Antiphilus of Byzantium).

Living close to the edge and without our million distractions, Greek poets wrote a great deal about two great subjects, the earth and the ‘everlasting and voracious sea’. Here is an anonymous epitaph for a fisherman who ‘died dirt-poor’ and is buried ‘close to the sea he frequented in love and fear’. Here are traders who reluctantly ‘begin the unremitting business of the sea again’ (Marcus Argentarius), pray for good weather, and know that their wives and mothers will worry. And there are several poems about naked bodies washed ashore and tombs which will remain empty:

I call the name of Timocles and scan

The bitter sea for the corpse of him and know

Grief on a stone will not haul in a man

Who fed the ravenous fishes long ago.

(Honestus of Byzantium).

Then there is the earth, and the struggle to survive in a hot dry country where clear springs are especially valued. If respected, Demeter will give you violets, hyacinths, ‘the tender leaves of curly lettuces, fresh-salted cheese’ (Philodemus), and Priapus, ‘guardian of the kitchen garden’ (Anon) will protect poor men’s little piece of land. But if men refuse to look after the earth, there could be an unimaginable disaster:

Do me no harm, I am young, I am a holy tree.

Cut me, I bleed. Bark me, I’ll stand for all to see

Dead, like a curse imploring the sky.

Best you believe all trees are holy trees

This poet, Antipater of Thessalonika (?), warns readers about the fate of Phaeton, who drove the sun’s chariot too close to us and created a world ‘home to nothing but dead everlasting life’. This translator is, of course, thinking about the Sixth Extinction.

In a coda, David Constantine adds two poem-sequences of his own, which ‘I would not have written but for my decades of close reading of The Greek Anthology’. ‘Spirals’ is about the harm which we are doing to ‘the other lives we share the planet with’. ‘Some Quatrains for a Primer of our Times’ is influenced by Brecht, who was also influenced by the Greeks, and is about war. He positively invites us to draw parallels with today’s events:

We too had laws of war: don’t poison wells

Don’t fell the olive trees (they take so long to grow)

Don’t bomb the schools, don’t bomb the hospitals ….

Stranger seeking our monument, look around you.

It sounds like the ancient poems which we have just been reading in translation, but, of course, I immediately thought of Gaza. It is wonderful to discover so many ancient poets (when so many others have been lost) and this is a book to treasure.

Merryn Williams lives in Oxford. She has published five volumes of poetry, and a pamphlet, After Hastings ( Shoestring Press). She translated the Selected Poems of Federico Garcia Lorca (Bloodaxe, new edition 2021), and edited and introduced The Georgians 1901-1930 (Shoestring, 2009), and Poems for the Year 2020: Eighty Poets on the Pandemic (Shoestring, 2021).

*****

The Shores of Vaikus by Philip Gross. £12. Bloodaxe Books. ISBN: 978 1 78037 717 9. reviewed by Tom Phillips

Everyone has a primary landscape. That part of the earth’s surface which we first consciously engage with as a child and to which we return, if only mentally, in order to calibrate or recalibrate our relationship to our surroundings. In his 28th collection, Philip Gross returns to a primary landscape which is simultaneously both his own and is not. Although born in Cornwall, the TS Eliot Prize-winning poet is the son of an Estonian refugee and it is Estonia which occupies geographical centrality in a collection that grapples with the strangeness of an unfamiliar landscape which is yet part of Gross’ inheritance whilst simultaneously attempting to come to grips with the vagaries of history, the phenomenology of deep time and the folkloric plenitude of Estonia’s forests and shorelines.

The book is divided into three sections – standalone poems or sequences of poems in two sections titled ‘Translating Silence’ (vaikus, we’re told, is an Estonian words for silence) and a lengthy prose-poem sequence called ‘Evi and the Devil’ which reads like a post-modern re-telling of classic east European folk tales, complete with esoteric characters like the Crane Beak Woman, Frog Feet Man and Glass Man as well as a Devil who ‘was quite deflated’ the last time narrator sees him. Not being especially knowledgeable about Estonian folklore, I can’t say how much of this narrative is of traditional origin or of Gross’ own imaginings, but there is certainly a feel of authenticity that extends beyond mere intellectual curiosity: a view of the world associated with the rich folkloric traditions of eastern European becomes felt through the interactions of Evi and her environment. However Gross writes about this landscape, in other words, the narrative and the poems that surround it are rooted in his own direct encounters with this country that he has somehow inherited through an accident of birth.

Right from the off, Gross’ acute attention to the sonic possibilities of language are readily apparent. In the very first poem, ‘The Old Country’, he stations himself on the edge of silence where he encounters ‘Not far, and not near,/scarcely sound, more a hitch/in the hush that insists/until I stop my breath and listen …’. As he goes on to say in the same poem, ‘So little can stand for so much’. Language is not merely a tool for expressing ideas or emotions, it has an aesthetic value in its own right. The chance echoes it provides (the sound-sequence of ‘hitch’/‘hush’/‘insists’ are ones that Gross makes full use of, pursuing the thread of his thoughts as much through language as through thinking and feeling). Numerous other examples appear throughout the volume, whether it be a metaphorical turn like ‘a deliberation of raindrops’ in ‘A Place Called Vaikus’ or the short, sharp realisation that Estonia is a place that has been overrun by multiple tyrannies where ‘all the trucks of history rolled through’ in ‘Evi and the Devil’.

At the same time, however, Gross is healthily dubious about the possibilities of language. Evi also notes that ‘I never believed the things words seem to point at could be all they are’ and suggests the existence of ‘Languages just off the coast of understanding’. And that translates into a physical world where ‘The real ghosts in this place aren’t dead. The dead are vivid … The ghosts are the ones who have given up on living.’ Or, again, in the poem ‘A Monument in Vaikus’, Gross wonders over a writer’s ‘Aim/for the word, the next one, not//right, ever. Just a shade less wrong.’

On first reading, The Shores of Vaikus is a rich and rewarding collection, thanks largely to the adept deployment of language in ways that provide a welcome aesthetic jolt, but it is also a profound reflection on belonging – not just only to our primary landscape, but to the earth as a whole. It’s perhaps not for nothing that many of the poems concern bleak shorelines littered which rocks whose granite ‘is in exile. Imagine the grief/of magma, expelled from the Earth’s core’. What we now know as deep time, the geological epochs that lie behind us, is always close to the surface while the trucks of mere human history traverse this vulnerable terrain.

From his earliest publications back in the 1980s, Gross has demonstrated a unique sensibility – both to the world and to the words we use to describe and attempt to make sense of it – and The Shores of Vaikus shows no sign of a slackening in his attentiveness. It’s a volume full of both vividly realised images (a flock of geese form ‘a ragged seam’ and ‘hitch/each to the other in a hundred-strong/single, first fluid then tightening vee/not clamorous, not soundless, but//the grandest act of quiet’) and ‘A stillness/that’s sudden, surprising, a gasp, a thrill – /all the things stillness is not supposed to be.’

Above all, perhaps, it is writing that links into the idea of anti-monumentality, a literature that exists in the cracks of literature and thereby asks us to question the assumptions we might have at a much more profound level than whether it’s Shakespeare or Marlowe, Dickens or George Eliot or, for that matter, Sunak or Starmer, Biden or Trump, Facebook or TikTok, McDonald’s or Burger King – a literature that has been gaining increasing momentum in east and central European writing in recent years thanks to authors like Olga Tokarczuk and Georgi Gospodinov. It’s a pleasure to read a volume of poetry that is so alert to the multifarious contingencies of history.

NB: Four poems included in The Shores of Vaikus were originally published in The High Window. You can find them here.

Tom Phillips is a writer, translator and lecturer living in Bulgaria where he teaches creative writing and translation at Sofia University St Kliment Ohridski. His own poetry has been widely published in the UK and Bulgaria, as well as in Colombia, India, Italy, Kosovo, Romania, Serbia and Slovenia. His translations of Bulgarian modernist poet Geo Milev are due to appear from Worple Press later this year.

*****

The Adjustments by Claire Dyer. £11.99. Two Rivers Press. ISBN: 978-1915048165.

Reviewed by Michael Loveday

Since 2013, Claire Dyer has published four poetry collections with Two Rivers Press, and her latest, The Adjustments, may be her finest yet. Her previous collection was the Rubery Award-shortlisted Yield (2021). Taken as a whole, the poems in The Adjustments seem even more consistently assured, and within the book’s generous 80-plus pages, a strong proportion of individual poems startle, mesmerise or linger in the memory.

While The Adjustments has plenty of the kind of poised and thoughtful lyric poems that appeal to the general reader, it is also dotted with experimental intricacies that will be a little dose of catnip for readers of adventurous, avant-garde poetry. This range and combination of interests makes for a collection that is likely to have wide appeal. Dyer is walking a very satisfying line here between the poet as self-aware experimenter (placing the radical aesthetics of the poetry itself in the foreground), and the poet working within the familiar mainstream of British free verse poetry, wholly in service to witnessing everyday life.

In this collection, Dyer is interested in how losses and separations affect us, and how absences must be weighed against the impulse to cherish and be consoled. In some poems, those consolations – arising from fleeting moments of experience – are enough: the narrator of ‘Perfect’ (p.2) offers a list of activities shared with a partner within the routine of a comfortable, ordinary day (drinking coffee, eating toast, walking beside a river, reading a book, or a small chore like varnishing a house sign). The poem concludes with resonant certainty: ‘It is / as simple and as perfect as this.’

Elsewhere, the impulse to celebrate life seems overwhelmed by the anguish of disconnection. ‘Non Sequitur’ (p.14) explores a cherished childhood memory of making Christmas decorations as a family, but the poem frames this in the context of a painful personal loss:

That was when I still believed

In snowflakes, love and fairy tales,

But will never tell you this, because

You are somewhere I can’t be,

drinking tequila shots in a bar

with someone who’s not me.’ (ll.19-24)

One of the biggest ruptures the speakers of these poems face is the devastation triggered by grief. Death is seen to spark incoherence and fragmentation – and simultaneously a blessed rage for order: ‘there’s such trying, trying / to make patterns from the unruly, the / unruly and the random. Nothing coheres. / And yet, and yet, […]’ (‘In these days of this dying’, p.33, ll.1-4)

Dyer acknowledges grief’s potential for duality, its fusion of disintegration and salvage, expressed in the same poem through in the image of Japanese kintsugi. The narrator imagines becoming a repaired object, anticipating that her loss will be made visible – kintsugi’s beautiful gold fault lines – as part of her physical self:

And yet, and yet, there’s

kintsugi’s celebration of breakage, of repair –

its gold-holding on, gold-holding in; […]

[…] there’s your hand, your heart –

the holding on, the holding in – how your going

will leave visible the loss, the leaving, on my skin.’ (ll. 7-9, 13-15)

Repair of this kind – consolatory, transformative – seems a fragile, ungraspable thing. In ‘Not only but also’ (p.45) a narrator describes a night of insomnia – apparently on holiday by the coast – where she goes to the window of her room and imagines her children pointing out aspects of the world outside:

[…] here, on the other

side of the glass, our children could be calling

Look as dolphins swim their running stitch

through the worried water of the bay,

calling Look and pointing

with their spotless hands to the boats,

at the frayed green, yellow, blue paint

of the gunwales, […]’ (ll.4-11)

These urgent, keen calls to witness remind her to cherish something about the world, before – in the final line – the unsettled narrator ‘get[s] back into bed, still sleepless next to you.’ (l.20)

Life’s paradoxes are well-evoked throughout: in one poem, an unnamed woman seems to offer a ‘stopped moment’ to a man, and the poem continues with an extraordinarily poised sense of intimacy:

She says take it. In his hands it is a globe and warm. […]

[…] She will always

be married to someone else, says

fill your mouth with it. He lifts his hands,

puts it to his lips; it stops the din, the horse

mid-gallop, the open-throated bird.

She says I am this silence, find me in this forever,

I’ll taste of longing and sweet figs.

(‘This Stopped Moment’, p.65, ll.1, 8-11, 13-14)

There is so much oppositional force and exquisite impossibility contained in this ‘stopped moment’, which eternally contains the woman (‘find me in this forever’) where she is forever unavailable (‘always…married to someone else’).

Visual images are a key device enabling Dyer to explore how the past keeps surfacing within daily life. In ‘Still the Girl’ (p.78) a memory of childhood identity persists into adulthood, with a photograph as evidence – perhaps a charm against the passage of time. Any time-stopping powers, however, seem outweighed by the final line’s subtle doubled emphasis, its liquid alliteration, and its plurality – all of which we might assume conquers that singular act of ‘keeping’:

And, I’m still the girl, the thin-armed girl

who was your girl. Here’s

the picture someone took for keeping

through the lifetimes and the leavings.’ (ll.17-20)

In this collection, too, Dyer balances the faithful record of physical phenomena with an interest in abstraction and the symbolic. More cerebral ‘thought-pieces’ such as ‘In the Matter of Silence I’ and ‘In the Matter of Silence II’ contrast with the heartfelt lyrics of everyday witnessing that are prominent elsewhere:

there is the silence after the word grief

and the word breathes the air that is its silence

is the silence after the word dying

the air in the silence that is its oxygen

the silence after the word always

it begins and ends with it […]

(‘In the Matter of Silence II’, p.4)

One poem’s protagonist even carries an abstract idea of memory carefully in a bowl, treasuring whatever qualities of experience can be retained:

[…] I carry the bowl into the now

that will become the before, and

the bowl is full of the empty

before, […]

(‘From This Before’, p.11, ll.8-11)

‘In Which A Fish Is Not a Fish’ (p.10) builds to a resonant climax that celebrates the holding of a fish in one’s hands for a short while. The poem’s title self-consciously broadcasts that the ‘fish’ is taking on a symbolic meaning:

remember it for itself, and its colours,

and you, leaning over the edge

of the boat, bridge, riverbank,

quay, cupping it in your bare hands,

holding steady for a while.’ (ll.14-18)

Whatever it is here that’s helping the narrator of the poem to ‘[hold] steady’, is up to the reader to decide. Dyer is capable of lines that seem wonderfully estranged from routine, everyday speech. Here are two examples:

she keeps countless

strongboxes in the attic of,

each the size of consolation.

In them are her sea storms,

and the ice, tempests that hurl

the trees, the leaves of,

at our feet […]

(‘Our mother’s house is built’, p.16, ll.4-10)

so far in this not trust is

safer than the truth is

when she does her thinking

in the dark that’s like wool on her face

and she’s unpicking him again and he is

never who she thinks he is

is a turning turning thing

or maybe he is maybe he is […]

(‘The White Towel’, p.68, ll.1-8)

There are a number of images of transformation in the collection, where a protagonist seems to transcend the constraints of being human. Dispersed through the book is a series of beautifully atmospheric poems entitled ‘The Woman Who Becomes a Field – I, II, III’ (the endnotes tell us these poems are ‘after Gift, by Mark Roper’), in which the female protagonist perceives herself getting closer to the natural world:

Now she is a field, she can collect the rain

from the leaves of ground elder and

hedge garlic, cabochons of rain to store

in the pocket of her second-hand coat; now

she can understand distances and horizons,

(‘The Woman Who Becomes a Field – II’, p.41, ll.1-5)

In another lively poem, the narrator and a ‘you’ descend together underwater and adopt the physical identity of fish:

Eight feet down it grew cold, the ocean was

a weight of darkness, and breathing

hard until our gills came,

our skin splitting to let in the air.

I heard you gasp, felt the joy as you kicked,

dived deeper, deeper.’

(‘Diving II’ – p.59, ll. 1-6)

In ‘The Frog Collectors’ (p.82), Dyer returns to the motif of transformation by mischievously teasing us with folk tale tropes and delivering a tale of transformation unfulfilled. Some children have ‘collected frogs // from the neighbourhood drains’ (ll.2-3)

And, when I said goodnight, I touched a kiss

to each fragile, marbled head. We woke, of course,

to catastrophe, all frog promises broken; footprints

the size of fingernails already drying on the concrete floor.’ (ll.11-14)

Instances of radical change or metamorphosis like these work in counterpoint with the more reflective lyric mode that is evident elsewhere – there is a vitality in the language of the collection that helps the speakers of the poems reckon with their sources of grief and anguish.

Pairings, groupings of poems, and short sequences also contribute to the rich layering of the book. Dyer, who is also a novelist, is steadily building a superb body of work as a poet. These skilful, carefully worked poems are exemplary acts of witnessing (of memories, relationships, and the phenomena of the physical world), and the book is a powerful inquiry into how we might come to terms with inescapable losses and separations.

*****

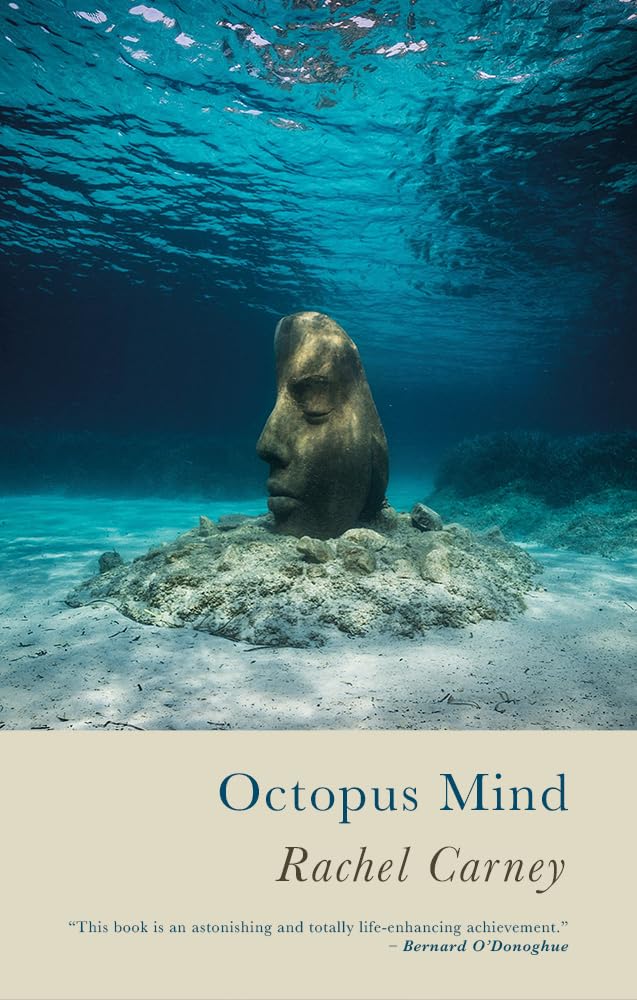

Octopus Mind by Rachel Carney. £9.99. Seren, 2023. ISBN 978-1-781-727102. Reviewed by D.A.Prince

Some collections are well-built — to borrow an architectural metaphor — and Octopus Mind is one of these. You might not notice this on first reading: it’s subsequent readings which reveal how carefully the poems are placed in relation to each other, support the expansion of themes, and how with the final poem the whole collection feels ‘finished’. Rachel Carney’s central subject is outlined on the back cover but it’s in the poems and their interconnection that we start to understand — and share — her experience: an adult diagnosis of dyspraxia.

Carney withholds this diagnosis until it emerges, shyly, in the fourth poem (‘The clues were all there, strewn out along the shore’), where she spells out the separate letters making up dyspraxia as though they were random flotsam washed up on a beach. Readers share this slow process of discovery, piecing the letters together, even as we are distracted by the details of bladderwrack, driftwood, waves and shells, our attention failing.

If I had stopped to look,

I would have seen the small soft body of a d

face down on the sand

This distraction represents the dyspraxic brain’s difficulties in understanding words and sounds, bringing them together to make sense. In ‘Dyspraxic’ Carney shows how even her computer fails to recognise her condition —

Microsoft Word underlines it

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxevery single time

in red, as if it isn’t real.

Of course not. How could it be?

It represents axxxxxxxxquirkiness, a body

xxxxxxxxxout of balancexxxxxxxx with itself.

The spacing within the poem — a technique she employs frequently and always with good reason — shows her sense of disjuncture, the cracks where language won’t join up, an inner wobble invisible to outsiders. Spacing is one way of depicting it; division is another. In ‘Dys’ Carney attacks the word itself —

I want to dys/

xxxxxxxxentangle the sly hiss

of dys, to dis/embowel the fraught

dis/ease of it, as it slips

xxxxxxxxxxxxin front, so sure, so certain.

Carney uses poetic technique to get readers alongside her sensory struggle while her mind: ‘… is doing back flips’ to: ‘… get your words into order to filter catch collate them to massage their possibilities into place’ (from ‘Two Seconds of Silence’, a prose poem). This is effective, and all the more so because she reveals her diagnosis and its impact within the context of poems reflecting a wider life and interests. It is a part of her, variously, as is her interest in creativity and how artists paint. Placing these early in the collection establishes a parallel world where it’s the artists who are struggling to achieve something that can be understood. ‘Impressions: after J.M.W.Turner’ uses the white space of the page to indicate his ‘suggestion’ and ‘illusion’ as a way of building up a painting. By contrast ‘Blue Nude: after Picasso’ focuses on the artist working as light fades, then into darkness, letting the painting find itself when he can no longer see —

carving her out of the backgroundxxx bringing her gradually

into the black cave of his studioxxx his painting

it is so dark he cannot see his hands anymorexxx she isn’t

even therexxx she never wasxxx and still

he paintsxxx until the town clock strikes three

a cat screechesxxx he stopsxxx breathes in

deeplyxxx and out againxxx it is over

he has spilledxxx the blue of himselfxxx out of himself

In the prose poem ‘Unremarkable: after Gwen John’ Carney’s use of repetition focuses on determination and persistence. Each section begins ‘A woman paints …’ and slowly versions of the scene and the artist emerge: a corner of a room, the slanted light, a table, an address. The poem summons up the constraints of John’s paintings, the close attention to immediate surroundings, and — most of all — the importance of concentration to the artist and how it allows her to be herself: ‘A woman paints because she can, because the universe allows her to.’

Building on this, Carney presents her own life visually on the facing page in ‘Exhibits in the Museum of Dyspraxia’, a list which includes —

A dropped dinner: smashed plate, spaghetti, bolognaise. […]

A cushion of air between the body and the mind.

The soft static between memory and recall.

A surge of words that settle on the floor, the chair, the sofa, ruffling their feathers, cooing, waiting.

A duvet cover, forever tangled.

Again there is plenty of white space, as in a display giving each ‘object’, whether real or surreal, equal importance and significance. These ‘objects’ re-appear in other poems: the ‘soft static’ becomes ‘the background hum’ in ‘The Lie, Dyspraxia and The Background Hum’; the feathered words feature in ‘Self-Portrait with Words and Feathers’. Carney is inventive with lists —and not just because routine is an aid — as in ‘Nine Brains at Midnight’, where the whirling confusion of mental activity militates against sleep. Caught up in this, and in other poems, are the difficulties of sustaining any lasting relationship and an ongoing alone-ness.

A rich and wide-ranging selection of metaphors from the natural world hold the poems together: a variety of birds, foxes horses and most obviously marine life, not just the octopus of the title but tides, shells, currents, shorelines, waves. They never overwhelm or dominate but work together, building up the whole. The title poem, and a companion ‘Octopus Self’, show weaving tentacles as they attempt to understand the competing demands of words, meaning, sense and how to respond.

In the lull afterwards, my octopus mind

reaches out its tentacles

to grasp the core of each word you spoke,

turning them over and over,

tapping them to see what might fall out,

squeezing them to see if they turn sweet or sour. (‘Octopus Mind’)

It’s a strong image, one I suspect most readers would relate to, and this is what makes the collection easy to enter: some aspects of dyspraxia are intimately familiar. Carney leads us further into how the condition manifests itself and also, in the triumphant final poem, how it is defiantly vigorous. ‘Self-Portrait as a Neurodivergent Tree’ shows her as she ‘…lumbers / through neurotypical streets’ , longing for the company of fellow trees —

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx…where each

xxxxxxxtree thrives in its own

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxanomalous, divergent space,

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxsending out its shoots in all directions.

It could end there, in solitude and disconnection; Carney, however, ends the poem — and the collection — on an affirmative note, which is both personal and also a reminder of what the collection achieves:

We trees stand proud,

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxhold out our canopy

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxadorned

in white and green —

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxthe mantle of our creativity

bursting into bloom.

The indivisible threads of dyspraxia/neurodiversity and creativity unite these poems and give the collection a structural coherence. Given Carney’s diagnosis this could have been a sombre book: instead, it balances pain with the riches a larger world can offer. It’s an inventive, often playful, outwardly-engaged collection which repays repeated reading.

D.A.Prince lives in Leicestershire and London. Her second full-length collection (Common Ground, HappenStance, 2014) won the East Midlands Book Award 2015. Her third collection, The Bigger Picture (also from HappenStance) was published in 2022.

*****

The Chaos of Desire by Marin Bodakov, trans. Katerina Stoykova. Accents Publishing. ISBN: 978-1-961127-11-1

The Bulgarian poet and critic Marin Bodakov died unexpectedly three years ago at the age of fifty. Drawn from across all eight of his Bulgarian poetry collections and ably translated by Katerina Stoykova, this volume of poems serves as both a tribute to a key figure in contemporary Bulgarian literature and a representative introduction to his work for English-speaking readers who’ve yet to encounter it.

As Stoykova observes in her introduction, even as a young poet, Bodakov emerged with a highly distinctive style and voice: “a few sparse words, each integral to building the structure of the poem. Nothing excessive or gratuitous. Yet somehow the atomic cage of the poem unlocked something inside the reader – released the trapped energy of unsaid truths.”

This remained the case throughout his writing life and none of the poems here could be said to outstay their welcome. They are minimalist, lapidary, often enigmatic, and yet do indeed release trapped energy as they pull together in unexpected ways words and images from or at least from the very edges of – as this collection’s title has it – the chaos of desire. The linguistic precision Bodakov continually sought – illustrated here by the inclusion of two subtly, but significantly different versions of a poem called ‘I can still see your breath’ – combines with unexpected series of incident and image to disturb conventional perceptions and give space for what the titular poem identifies as ‘the unpronounceable’ and ‘the unbearable’.

The unusually long – for Bodakov – ‘To Gretz, Against Time’ opens with a dream-like paradox:

In the blistering temple

of my last years,

the young man I wanted to be

calmly enters with his dogs

and doesn’t notice me at all.

From the outset we are in a world which, much like those made visual by artists like de Chirico and Magritte, is haunted by enigma, in this case originating in the conflation of time, the defamiliarizing adjective ‘blistering’ attached to a temple and the provisional nature of an alternative younger self. The poem then moves into a sequence of images that defamiliarize this world even more:

A friendship rains, and stops,

the breeze of light stirs the blossoms,

here and there the destitute pray.

In their own right, each of these lines is open to relatively straightforward interpretation – a rain shower as metaphor for failing friendship, ‘the breeze of light’ as a form of synaesthesia, the desperate faith of the destitute – but they also initially appear only tangentially connected unless, that is, we apply the precisely the kind of surrealist logic made manifest in de Chirico’s ‘The Enigma of Arrival’ or Magritte’s ‘L’Empire des Lumières’ that invites us into a fuller understanding of the complexity of our observations, perceptions and associative generation of meaning and value.

At times, perhaps, the poems invite a more firmly allegorical interpretation – in ‘Here’, for example, we find ourselves in ‘the tourist zone of unhappiness’ – but, for the most part, places, objects, incidents occupy a less easily defined space triangulated by emotion, thought and the brute fact of the actually existent, as in the short five-live poem ‘Growing Sense of Departure’:

I surfaced

with a ballad on my mind:

An elderly couple at the market,

We cannot afford this apple, sweetheart –

and they walk on with dignity.

Somewhat inevitably, William Carlos Williams springs to mind and there is certainly something of ‘The Red Wheelbarrow’ running beneath this poem – and, in fact, many others in the collection – which encourages us to reflect on the ‘So much’ that ‘depends’ on an apparently trivial detail such as the overheard use of the word ‘sweetheart’ in this particular context and how it comes to make ‘dignity’ seem like precisely the right quality to apply to their walking away. Never mind that the poem also embraces the notion that such an event might deserve ‘a ballad’ – the attention of art – as much as, say, some more ostensibly grandiose subject.

The risk inherent in such minimalist poetry, of course, is that it can become little more than an ironic shrug. Even in his most aphoristic moments, however, Bodakov circumvents this by offering thought-experiments rather than fully realised, closed circuit observations. The question expressed in ‘With Altered Voice’ – ‘How should we measure/the braking distance of emotion: in meters, months?’ – seems simultaneously absurd and entirely rational, much like the question of how Schrodinger’s cat might be simultaneously dead and alive.

It’s very important to point out too that, for all his interest in language, thought and perception, Bodakov’s poems are not dryly cerebral. His subjects are at the heart (in all senses of the word) of human experience – love, death, birth, loss, grief – and the poems addressing the death of his own father are extraordinarily powerful as are those that speak of love. One of the poems concerning his father’s death, ‘Mud on my Palm’, ends with the starkly simple couplet ‘I finished burying my dad./I wish this were a metaphor’, while ‘Shallow Vein’ – a love poem that touches on the physicality of desire – concludes that the eponymous vein is ‘the only jewelry/worthy of you.’

In translating, collating and publishing this collection, Katerina Stoykova has done a great service in bringing to the notoriously translation-shy Anglophone world the work of a poet whose poems, as Andrew Merton says on the book’s back cover, ‘rank alongside those of his contemporary surrealist masters – Charles Simic, Mark Strand, Octavio Paz, Nicanor Parra’. The brevity of the poems means that it’s a book that can be read in an hour or so, but that would be to miss the astonishing depths into which Bodakov is capable of leading us.

NB: Four poems by Marin Bodakov poems, translated by his widow Zornitsa Hristova, appear in The High Window’s 2017 Bulgarian supplement.

Tom Phillips is a writer, translator and lecturer living in Bulgaria where he teaches creative writing and translation at Sofia University St Kliment Ohridski. His own poetry has been widely published in the UK and Bulgaria, as well as in Colombia, India, Italy, Kosovo, Romania, Serbia and Slovenia. His translations of Bulgarian modernist poet Geo Milev are due to appear from Worple Press later this year.

*****

Backalong by Nia Broomhall. £7.50. Bloodaxe Books / Mslexia. ISBN: 978-1-78037-716-2. Reviewed by Judith Taylor

This first pamphlet from Nia Broomhall, the winner of the 2023 MsLexia Women’s Poetry Pamphlet Competition, takes its title from a Somerset dialect word, and sense of place shapes much of the collection, not least in the sequence of seven ‘Somerset Sonnets’ that thread it through. It’s an often ambivalent presence: the second sonnet, ‘My Parents’ Accent’, celebrates the sense of home in their voices:

…. They sound like open fields and green

and blue. They whisper wisps of hay right down

the 303 behind an HGV.

but goes on to say how: ‘with them, my voice sounds like that too… / … but it can’t hold’.

Undercutting any sense of belonging, poems like ‘Nevicata’ or ‘Nonostante’ invoke memories, and fragments from the language, of an Italian grandfather who came:

‘to work, to say I do in English in a church

that wasn’t his’ (‘Nonostante’)

and the landscape itself fluctuates, changed by time and by economic and climatic upheavals. The fifth sonnet, ‘Hedgerow’, calls up in beautifully-chosen detail a laid hedge, but sets it against the cheaper alternative:

The blade is quick but leaves behind

a scream of bone-white splinters, rachetings

of birds into a cold and lidless sky.

while the visual poem ‘In Eleven Hours’ takes the shape of the roof of a house about to be overthrown by floods.

Alongside this theme of instability of place is that of personal grief. The opening poem calls the collection’s dedicatee ‘Nina, who is still here’, but goes on to explore the ways in which that is and isn’t so, and the poems return frequently to this loss, and to how it can be grappled with in poetry. Some lean on the deliberately bald language of attempted acceptance, as in ‘Three ways to look at it’, or in the undermined lyricism of ‘Tulips’, which begins with the speaker planting flowers on ‘a blue/day that smells of earth’:

.. but she will still

be gone. I will plant them

anyway. She will still be gone.

Others take a more slant and defiant approach to reality. ‘Folly’ opens somewhere ‘We talked about coming …We never did’ but moves through the falsity of the ‘follied place’ itself and its deceptions (‘Flood the tilework and call it a lake – / the fish won’t know’) to the construction of a new memory:

I remember when we came here. There were twelve cygnets.

She stood in the window, and her hair flew around her face.

And the second-last poem, ‘Collect’ starts in surrealism, and uses an elaborate riff on penguins and orcas coming to visit, to keep at bay for as long as possible the truth of who these black-clad visitors are: …they / took her, and they said that they were sorry.’

The last sonnet pulls the thematic threads together, examining the ambiguities of the word ‘backalong’ and how it might be used to blur or blunt the losses time imposes.

This close attention to language and its malleability flows throughout the collection: in pauses to delve into particular words; in the alert and fresh choices of imagery in poems like ‘My Parents’ Accent’ or ‘Still’; and in the serious word-play of ‘Collect’ and of ‘Ajar’, a poem shaped like a lost ginger-jar that goes on to consider ‘the space where you stand in / the light from the open door’. The experiments Broomhall makes with form work well in tension with the sonnets, and the concrete poems in particular pay off: indeed some of the more metrically conventional poems are put in the shade – I felt that the three ice poems, in particular, might have been been better separated rather than presented as a triptych, where the tour-de-force of the first, concrete, poem rather undermines the other two. But that’s a minor quibble. This is a small collection that packs a lot in, in technical as well as in emotional terms, balancing attention to detail with its larger themes and with many moments of spark and recognition on its elegiac journey. A strong debut from a poet I look forward to hearing more from.

Judith Taylor lives in Aberdeen, where she co-organises the monthly ‘Poetry at Books and Beans’ events. Her latest collection, Across Your Careful Garden, is published by Red Squirrel Press. She is a longtime volunteer with Pushing Out the Boat magazine, and one of the Editors of Poetry Scotland.

*****