*****

Sarah Holland-Batt: The Jaguar: Selected Poems • Helen Ivory : Constructing a Witch • Susan Utting: The Colour of Rain • Ghareeb Iskander: English Poetry and Modern Arabic Verse: Translation and Modernity • Julian Orde: Conjurors • Sam Smith: Mirror, Mirror, In the Geography of the Head • Caroline Maldonado (Poems) and Garry Kennard (drawings): Michelangel, Mirror and Stone

*****

The Jaguar: Selected Poems by Sarah Holland-Batt. £14.99. Bloodaxe Books. ISBN: 9781780377049. Reviewed by Edmund Prestwich

Sarah Holland-Batt’s The Jaguar: Selected Poems is a very substantial volume bringing together work from her three collections published in Australia. Its sumptuous production chimes happily with the style of her writing: culturally sophisticated and highly intelligent as she clearly is, it’s above all the seemingly effortless sensuous evocativeness of her work that makes an impression from the beginning. Bloodaxe’s generous spacing and the poet’s fine rhythmic sense allow these impressions to flower in the mind.

‘Exhaustion’, from Aria, the first collection represented here, can illustrate the physicality of Holland-Batt’s writing at the basic level of literal description:

One afternoon I went into his silent study

and found, behind the tidy compartments

of paper-clips, rubber bands and push-pins,

an old, red tin – the relic of my grandfather’s oils,

wedged at the back of things. Horse-hair brushes,

graphite stubs, a frayed bit of string. And nestled in

the smudged stippling of china white and cerulean,

a solitary tube of cobalt blue, its crimped end

folded over and over until nothing was left.

Well written and promising though this poem is, it seems to me to have clear limitations in itself. We’re to learn more about Holland-Batt’s grandfather – an English architect and artist – and much more about her own father, whose study this perhaps describes. And of course the contents of the tin, particularly the folded and refolded paint tube, metaphorically express the idea of exhaustion in general and invite us to reflect on its different manifestations. However, the relation between the literal and the metaphorical levels of meaning in this poem is relatively static, and you need to read the poem as a whole for it to emerge, as it does in that haunting last line. What’s already exciting about most of the poems in this first collection is how sensuous perception is heightened and vivified by the transformative power of the poet’s imagination and by her ability to fuse differing modes of perception. In the first three lines of ‘Late Aspect’, for example, synaesthetic metaphors describe the sounds made by windchimes and cicadas in terms of tactile, kinaesthetic and visual sensations. Sensuously quickening our imaginations in this way, and personifying the night, Holland-Batt is able to give concrete force to the abstract sensation of being a bystander to the night in line 4:

As for the veranda: it is empty.

A windchime sieves the air, and the cicadas

emerge like metal stars.

The night is preoccupied with its own story

Such lines are a pleasure to say partly because of the sensitivity with which their cadences make impressions succeed each other as if we were bodily present on the veranda, listening, looking about, noticing one thing after another and thinking about our place in the scene. In this way they’re typical of how scene-setting and description work in The Jaguar as a whole.

Another way in which Holland-Batt’s transformative imagination works is in bringing pictures to life or using pictures as doorways to her own creative scenarios. A lovely example is her 13 line poem ‘Athenian Jar’, apparently based on Exekias’s famous black figure amphora showing Ajax and Achilles playing a board game. Stepping through Exekias’s image with its austerely limited black and red colour scheme, Holland-Batt makes Ajax address Achilles in a way that creates a living vignette in which time moves in the stillness, in which sounds are heard as well as sights being seen, and in which we are drawn into the speaker’s own internal bodily awareness:

Night strangles the island, cousin,

yet we play on and on. Absence thickens

my throat. In its hollow your spear

clinks on marble, moonlit

rats scatter like obols, and a ring

of mesh gleams at your neck.

In the second half of this remarkable little poem, such sensuous evocativeness becomes merely the starting point for a tantalisingly elusive shimmer of suggestions about the sad vanity and inescapable necessity of the two heroes’ efforts, perhaps with implications for human effort in general. There’s a resonance with the paradox of stillness evoking motion in Keats’s ‘Ode to a Grecian Urn’, but also, I think, a more distant resonance with Holland-Batt’s father’s situation as it is later revealed.

In fact many of Holland-Batt’s poems take their overt inspiration from pieces of art, music or literature. Clearly these things are of immediate intrinsic importance to her. The poems that result are rich simply as responses to the art works in question. However, I think they’re also a way of obliquely crystallising emotions rooted in personal experience, in line with High Modernist thinking about artistic impersonality. So, I think, are poems of landscape, in her native Australia and in America and Italy. Poems from her first two books – Aria and The Hazards – give glimpses of what seem to be personal stories related to these objectified emotions. It’s in the third book – The Jaguar – that this narrative mode is most fully developed. In particular, there are many moving poems about her father, about his life in England and then in Australia, to which he emigrated. We learn that he suffered from extreme neurological degeneration and incapacitation as a result of Parkinson’s Disease, undergoing what ‘The Gift’ describes as a seventeen year long process of dying or rather of waiting impatiently for the release of death:

In the garden, my father sits in his wheelchair

garlanded by summer hibiscus

like a saint in a seventeenth-century cartouche.

A flowering wreath buzzes around his head –

passionate red. He holds the gift of death

in his lap, oblong, wrapped in black.

He has been waiting seventeen years to open it

and is impatient. When I ask how he is

my father cries

What’s remarkable, both disturbing and poignant, is how strenuously objective the poet is in describing her father’s suffering. ‘Garlanded’ and the simile in line 4 suggest emotional detachment by their sheer startling incongruity, though reflection reveals a deeper aptness to this incongruity: many of the saints so portrayed would have been martyrs. The image of the gift of death, reminiscent of Rilke, again acts as an emotional filter, distancing and depersonalising the daughter’s account. As the poem develops, it details the father’s pain and degradation and shows the daughter’s helplessness to alleviate it, culminating in the stoically toneless, ambiguous recognition that

I will carry the gift of his death endlessly,

every day I will know it opening in me.

The final sequence, ‘In My Father’s Country’, takes stock of her father’s life with an apparent candour reminiscent of Confessional poetry but in a way that leaves response to the reader, without the emotive pressure I associate with the confessional genre. It’s also without the fizzing linguistic and metaphorical exuberance of most of her other poems. Rightly so, much though I enjoyed those qualities when they were present. The sober plainness of all but its first poem is vital to the impression of clear-sighted honesty that the sequence gives. As well as being moving in itself, this gives the whole volume a powerfully dramatic shape. After all the playfulness and transformative energy on display earlier, in its climax the poet seems to confront hard, inescapable truths head on.

I hope I’ve managed to convey something of what makes this such an enjoyable and richly rewarding book. It’s only fair to say what it doesn’t try to do. This is a book of Art with a capital A. Poetry with such a finely burnished finish, whether focused on sculpting beautiful cadences and patterns of sound and achieving the maximum sensuous evocativeness, as in most of the volume, or on achieving the maximum analytical clarity, as in the final sequence, doesn’t offer the illusion of impromptu conversation or spontaneously shifting thought, so we have little of that sense of the poet as a relaxed, intimate interlocutor that is one of the pleasures of reading Elizabeth Bishop, Fleur Adcock, or any number of more minor figures. What we have instead is a thrilling sense of almost total immersion in or absorption by a world of heightened physical presences and intensified feeling. In what were to my taste less successful poems the effect could become too rich but taking the book as a whole I enjoyed its artistry and illuminations immensely.

Edmund Prestwich grew up in South Africa but has spent his adult life in England where he taught English at the Manchester Grammar School till his retirement. He has published two collections: Through the Window with Rockingham Press and Their Mountain Mother with Hearing Eye.

*****

Constructing a Witch by Helen Ivory, cover art Helen Ivory and Martin Figura, £12.99. Bloodaxe Books, ISBN: 978-1780377193. Reviewed by Hilary Hares

For countless ages witches have been constructed from myth and fear, built out of the half-known in order to feed our need to control things which we do not fully understand. They’ve been silenced by the scold’s bridle, pelted with rotting vegetables in the stocks, ducked on the infamous ducking stool and occasionally even drowned. Whether they are deserving of the poor billing they often get, however, is debatable and this is expertly explored in Helen Ivory’s latest collection, Constructing a Witch.

Clearly based on extensive research, the poems approach witches and witchcraft from a range of angles. We meet specific witches, delve into the realms of the Pendle and Salem witch trials, encounter a number of different spells and even visit the Witchcraft Museum. Helen Ivory’s monumental imagination explores the world on the slant and, by the author’s own admission, a lot of the poems examine where all this has come from. In so doing she celebrates those traits which have become so taboo: ‘- why must we be so occult? I hold / up those rekindled women and we reel, we howl, and we / shoot our filthy mouths off’

Woman was doomed, perhaps, from the start: ‘When Man uncreatured himself’, Adam and Eve both failed the first test: ‘though it was decreed she failed it more’ from ‘Thus men forgot that All deities reside in the human breast’ (William Blake). A woman’s ability to shape-shift in an attempt to escape the shackles of the mundane was easy to misconstrue and from there it was a short step to vilification. We learn that: ‘Some definitions of Witch’ ranged from: ‘Midwife of shadows / low vixen with blood on its maw’ to: Barefoot earth-listener, / older than God or television’.

The Makings’, in which a puppet is burned in place of the suspected witch herself, graphically illustrates how witches became de-humanised:

The wails didn’t matter

because she was not human

she was barely a she;

a barren nothing, a wraith

fused together by spite.

Poems, like spells, rarely become manifest but one intriguing aspect of the collection is the fact that it contains a number of illustrations (in the form of collages) which are inspired by the handmade poppets in the Museum of Witchcraft at Boscastle. These delicate little artworks are also crafted by the writer and are made out of ‘found’ materials and illustrated with words and phrases ‘borrowed” from old books of fairy tales. This ensures that they are ‘charged with their own power’. They are also imbued with a quaint kind of Victorian mystique which assists in bringing the underworld of witches to life in a very visual way.

As children, our curiosity lapped up the myths that revolve around witchcraft: curdled milk, black cats, witch’s nipples. In: ‘The Devil’s Mark ‘there is: ‘A proof of how Satan raked an owner’s claw / across the parchment of my skin’. [ …] A blood red freckle here / a stain the cast of a skull, on my behind’. In their time all these signs and more were considered legitimate proof that the woman was a witch.

In addition, so many characteristics of being a witch derive from those things which women have traditionally kept hidden – menstruation, childbirth, menopause. In ‘The Menstruous Woman’:

A female body, tricked and out of whack

adjusts to wearing kindly black

to shroud the purpling of her clothes,

Such women are: ‘unreliable; leave work early – / say, twenty years too soon.

As the collection unfolds, a number of renowned witches appear to tell their stories. In Salem, Bridget Bishop is castigated by Judge Corwin for being: ‘that slatternly Eve / titivating her ribbons in the dress shop window’, while the tale of Lilias Adie, a kind-faced elderly lady who was said to have had sex with the Devil, is recounted through the medium of a podcast.

In several poems spells are updated and skilfully applied to twenty-first century suffering – domestic violence: ‘Disarming Spell: The Enchanter’ and body image: ‘Summoning Spell: The Body’… ‘Midwife your very body home / from every shabby playboy den’.

The closing poem seeks retribution for the slights and misinterpretations which have plagued women across the ages. It grants every woman the right to transmute into: ‘The Spirit of the Storm’ – ‘why not grow snakes for hair,’ […] ‘You’ve earned this wrath, don’t squander it / on slapdash chores and sundry empty tasks’.

Helen Ivory is a past-master of atmospherics and this collection drips with intrigue. Its power lies in setting the record straight and there’s a magic in her words which is hard to resist. As a result this encyclopaedic little handbook of witchcraft is likely to become a well-thumbed companion on every poetry bookshelf. It is no surprise that it is also one of this year’s Poetry Book Society’s recommendations.

Hilary Hares’ poems appear widely online and in print. She has also achieved success in various competitions. She has an MA in Poetry from Manchester Metropolitan University and her pamphlets; A Butterfly Lands on the Moon, Red Queen, and Mr Yamada Cooks Lunch for Twenty Three are available through: www.hilaryhares.com

*****

The Colour of Rain by Susan Utting. £11.99. Two Rivers Press.I SBN: 978-1-915048-15-8. Reviewed by Alex Josephy

How to summarise the effects of a whole collection? The Italian word often used for a poetry collection is ‘raccolto’, a harvest, and I’ve found myself reading The Colour of Rain with that definition in mind. There is so much gathered here. The lives of girls and woman are a central focus; Utting’s poems are peopled by sisters (including an imaginary one), mothers, daughters, wives, a Sunday School teacher, a suspected witch. And Nature in all her forms is a consoling presence throughout the book, marvellous, resonant and endangered.

Themes and images are interwoven, illuminating each other in much the same way that metaphors do. Painful girlhood memories of boarding school or possibly of life in an institution, and reflections on other women’s difficult but often courageous lives, sit alongside close connections with the natural world, and above all the mind-expanding pleasures of visual and language arts.

The first section is full of trees. The opening poem, ‘You have to be there’, invites us to walk beside the poet:

…to dream yourself out of your

skin into your stride, till you are all

rhythm, a three-four signature…

and into the company of trees:

…the shivering poplars sharing

their secrets, their breath, with yours.

Consciously embodied, and leaning closely into the natural world (‘I want to be a tree right now’, ahe exclaims in ‘Loving Trees’), Utting sets a tone of hope and solace, modified in later sequences by poems that explore pain and isolation. The penultimate poem asserts, of a girl scalded and scarred ‘she was not a tree…she was a small girl of flesh, blood and skin’, but she is a girl undefeated by damage, carrying :

…the shine of a pressed satin sleeve, that marked

her survivor. Her arm with its beautiful scar.

Poem after poem achieves this heart-wrenching clarity, examining life’s cruelties but also attending to small details, moments of beauty and possibility. Utting slips easily between carefully observed realism and dream or fantasy. When she becomes one of a group of willows, both woman and willows are vividly present:

…so close and sisterly we shared

a hairdo. Our stringy locks were free to dangle,

shiver, dance a fidget to the wind.

I was moved by ‘The Innocence of Trees’, in which pine trees walk ‘all night’, perhaps attempting an escape:

They meant no harm, the pines,

not a twig or sprig of harm among them…

…one foot after another

and side by side, as if there were

no vanishing point.

Utting has the skill of writing from the heart, while paying the most careful attention to craft. Many of the poems are in free verse, with quietly innovative use of form, word music and rhythmic patterns which seem to fall effortlessly into place. She plays with versions of sonnet form, and there are two poems modelled on Chistopher Smart’s iconic ‘My cat Jeoffrey.’ Of these, I especially enjoyed ‘Let Us Give Thanks for Knees’, a delightful meditation on the knees of schoolgirls, with all their itches and scabs and potential sexiness, and the comforts they might afford:

…For when the lights go out

they let us curl up small in bed, like ears,

like shrimps, like winkles in their shells.

In a sequence of ekphrastic poems, Utting is able to approach her themes from fresh angles. My favourite of these is probably ‘Maman’, after Louise Bourgeois’ giant ‘maman-spider’. The tangled emotional impact I remember feeling when I visited this artwork – radiating dread at the same time as a kind of passionate vulnerability – is here in the poem, evoking the way women have so often been silenced (‘I don’t know where to find/ a mouth’):

All I have is an effigy of

maman, marmie, mummy, mother, ma,

an eight-legged effigy of silence,

of something missing; missed.

Artworks allow the poet to empathise with women surviving infirmity, imprisonment, homelessness: in ‘Afaz/Cages’ after Susan Hefuna’s drawings of Egyptian latticework screens, she insists on women’s resilience:

Grids can be beautiful, they let in air…

…Cage walls – remember and believe –

can be unwoven, can be breached.

In an earlier poem, Rousseau’s tiger is imagined surrounded by its cultural references, ‘exoticised, spectacular and jungle fierce’, heading for extinction, to be viewed before ‘I am no more / than rumour, before I’m history.’ A masterly (I wish we could say mistressly?) cascade of rhymes sweeps the reader along from ‘tapestry and marquetry’ through ‘fantasy’, ‘taxidermy’ and ‘greenery’ to ‘history’.

The final section is, I think, mainly concerned with the girl who has appeared briefly earlier, and who endures serious injury and recovery in the final few poems. I take this sequence to be connected and to tell something of her story. In ‘Imagine This:’, she is four years old, and seems abandoned in a cold institutional setting, bitterly unhappy, ’And they tell you that you’re loving every moment of it’. She is depicted as a little prisoner, reciting fairy tales to soothe herself, ‘safe from the beating of wings through the night’. Her story resonates with those of the other women caged in unfree lives in the preceding poems. She is isolated even from other girls around her, ‘marooned on an isle / of herself’. The powerful depiction of her isolation ripples back through the collection, reminding the reader of its other silences.

But Utting’s poems never leave the reader in a place withut light. Her emotional wisdom and delight in writing are always present. Her ‘girl’ is not afraid to resist the darkness and oppression, ‘on detention again, for insubordination’. She is the kind of daydreamer with whom many poets are likely to identify. And joyfully, she knows the value of imagination and where to find sources of inspiration, as Keats did:

…the value of the nothing in

her head:

xxxxxxxxxxxxxthat painted place that zigzags,

coils and skitters her to other lands, to anywhere she fancies,

xxxxxxwhere they know the priceless,

fiery possibilities of indolence.

I love the way ‘fiery’ and ‘indolence’ brought so close to one another make just as good an oxymoron as the original one in Keats’s ‘diligent indolence’! In ‘Ingathering’, the girl hoards and relishes words. Every noun and verb choice in the poem celebrates this pleasure:

Her head’s a tabernacle full of language…

…a scalloped tent

against the wilderness, where she and her

ingatherings may sojourn, flourish, thrive.

Earlier, she ‘doesn’t say it because it hurts her tongue.’ But in these pages, she’s saying it now.

This is Susan Utting’s fifth collection. It is emotionally sure-footed, written with practised ease, and full of fresh, unexpected turns. In my favourite poetry collections there is often at least one poem that teaches me something completely new. In this one, it’s ‘The Resonating Properties of Spiders’ Silk’. Who knew that in Japan, a set of violin strings have been spun out of thousands of strands of spiders’ silk? The final lines say something about poetry, too:

this sweet reverberation,

this joyful, airborne noise.

Alex Josephy lives and writes in East Sussex and Italy. She has worked as a teacher and university lecturer and as an NHS education adviser. Her published collections include Again Behold the Stars, a Cinnamon Press pamphlet award winner, 2023, and Naked Since Faversham, Pindrop Press, 2020. Her poems have won the McLellan and Battered Moons prizes, and have appeared widely in magazines and anthologies. Her third full collection, A Little Bridge, will be published by Pindrop Press in 2025.

*****

English Poetry and Modern Arabic Verse: Translation and Modernity by Ghareeb Iskander. £29.99, I.B. Tauris/ Bloomsbury. ISBN: 9780755639939. Reviewed by Jenny Lewis

As the first study to examine the Arabic translations of major modern poems in the English language, English Poetry and Modern Arabic Verse by Ghareeb Iskander is described by Michael Beard (Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Dakota) as ‘less a work of literary criticism than a dialogue between poets’ which excels when it is ‘tracing the grain of multiple translations [and] illuminating subtle differences between the aesthetic possibilities of English and Arabic and between the visions of individual poets’. Iskander himself says his aim is ‘to explore the relationship between translation and modernity, looking at how translation creates modernity’. Based on his PhD dissertation at SOAS in 2018, the erudition and specificity of Iskander’s scholarship will be hard to do justice to by a non-Arabic speaker such as myself, however, although I was unable to fully appreciate all the linguistic nuances, the way the book is constructed – showing chapter by chapter the situational and verbal contexts of the poems under discussion as well as an informed and in-depth analysis of themes, interpretation and prosody – proved fascinating and educational. Iskander sets out to show that the translations from English into Arabic of modern poems, such as T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself, Ezra Pound’s ‘The River Merchant’s Wife: A Letter’ and Edith Sitwell’s The Shadow of Cain contributed greatly to modernity in Arabic poetry. Iskander is an award-winning poet as well as a respected translator himself, and it is this comprehensive, hyper-aware quality I found particularly engrossing about his methodology as I was led on a journey of discovery of how the leading poet-translators of their day, Adunis and his collaborator Yusef al-Khal, Tawfiq Sayigh, Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, Saadi Yusef and Badr Shakir al-Sayyab each brought his own particular knowledge and sensibilities to the task with very different results.

Iskander himself is a fine poet whose own journey as a translator began in 2009 when he studied nine English translations of al-Sayyab’s Unshudat al-Matar – ‘Hymn of the Rain’ (1954) for his master’s degree. The experience, says Iskander, ‘opened my eyes to the interaction between the original poems and its translations creatively and culturally’ and showed how English translations could ‘manipulate’ readers specifically in the Iraqi system. In 2013, Iskander was invited to join a Scottish workshop called Found in Translation in which four Scottish and four Iraqi poets translated each other’s work. As he says, the discussion was through interpreters as most of the British poets did not know Arabic and vice versa. In this way the process was creative rather than ‘translational’ and the resulting poems accepted as a collaborative job between writer and translator which raised the poets’ awareness of the poetic potential (and challenges) of each language. Iskander worked mainly with the Scottish poets Jen Hadfield and John Glenday and his poem ‘Gilgamesh’s Snake’ later became the title poem in his prize-winning full collection Gilgamesh’s Snake and Other Poems (Syracuse University Press, 2016) as well as a powerful film poem by Roxana Vilk http://roxanavilk.com/gilgameshs-snake

The first section of English Poetry and Modern Arabic Verse starts with an account of why The Waste Land appealed so much to pioneering Arab poets. Eliot started to write it when he was recovering in convalescent homes from serious depression in 1921 and its themes of personal fragmentation and universal breakdown, encompassing the horrors of the Second World War and, in the words of the Iraqi-Palestinian poet Jabra, ‘the Palestinian debacle and its aftermath’, struck a powerful and immediate chord with poets in the Middle East recoiling from their own experiences of war and displacement. In different versions of ‘Burial of the Dead’ (with its theme of resurrection) Iskander shows us how individual interpretations, word choices and prosody produced very different versions. One small example is the translation of ‘the Hanged Man’ (ST. 55) which varies between ‘the man executed by hanging’, ‘the executed’ and ‘the hung man’. The latter, by Sayigh, refers to the Tarot card image of the man hung upside down (but not hanged) in ST 47 – suggesting very different cultural allusions of sacrifice and divination. The second chapter looks at translations into Arabic of Whitman’s ‘Song of Myself’ showing how the movement of free verse revolutionised modernist Arabic poetry. Iskander’s own deep engagement with Whitman can be seen in his poem ‘On Whitman’ in which he personalises ‘Song of Myself’, here reproduced in the translation by Jen Hadfield in 2014.

I sing myself

In your final song

I sing you

In my final song

How can both

Be written then?

The grass you suppose to be oblivion

Remembers now

The delight the forerunner of the word.

Whitman himself said of his collection, Leaves of Grass (in which ‘Song of Myself was first published’) that ‘when you touch [the book] you touch a human.’ What Iskander’s study does is to put us in touch not just with world poets but also with the ‘humans’ who translate them. As well as the deep engagement with language that this book demonstrates, this, to me, is perhaps its most important achievement – to encourage the reader to reach out and touch minds who think in other languages and yet who feel in the same language that we all do.

Jenny Lewis’s recent work includes From Base Materials (Carcanet, 2024) and Let me tell you what I saw (Seren, 2020) a translation with others of extracts from the Iraqi poet Adnan Al-Sayegh’s epic anti-war poem, Uruk’s Anthem. Since 2012 she has been working with Al-Sayegh on an award-winning, Arts Council funded project, ‘Writing Mesopotamia’, aimed at fostering relationships and better understanding between Arabic and English-speaking communities.

*****

Julian Orde, Conjurors, Carcanet, £14.99, 9781800174559. Reviewed by Ian Pople

Julian Orde was a granddaughter of the Duke of Wellington and presented at court as a debutante. Later, she became a girlfriend of W.S. Graham, and a single parent at the centre of some of Bohemian London in the war. She also had a career as a very successful copy writer for a major London advertising agency, as well as acting and writing plays for radio and television. She published around twenty poems in her lifetime, although her poetry continued to emerge after her untimely death in 1974.

Conjurors publishes some 80 of the 150 extant poems found in packets belonging to Orde’s friend, David Wright. The back cover of Conjurors claims that Orde is ‘a major poet’ without whom ‘it’s [now] hard to imagine the middle of the twentieth century.’ Be that as it may, what emerges from these poems is a poet who was immensely technically gifted and who had absorbed the influences of Dylan Thomas and Graham in his Apocalyptic phase. Orde clearly used those influences and her own feeling for surrealism to create poems which always feel necessary and are couched in a personal voice which is there from the beginning.

The central poem here is the title poem, ‘Conjurors.’ This is a long meditation on the emergence and transformation of eggs into caterpillars, then the pupae and finally the butterfly. I use the word, ‘meditation,’ rather than the more obvious ‘conceit.’ The wonder that Empson picks out in Orde’s writing here is one that emerges from a furiously detailed observation. And the observation leads to a very conscious poetry as if the metamorphosis of the caterpillar were, almost, the metamorphosis of poetry. The poem has thirty stanzas and this is stanza nine:

Chosen as conjurors and given

xxxxxxxCells that bloom like water flowers,

xxxxxxxxxxxxxThey do not play

xxxxxxxxxxxxxBut heartily try

To prove with perfect conjuring

xxxxxxxDear life, if dear enough, allows

xxxxxxxA blind dive into a hatful of shadows.

Orde’s rhyme scheme is, A/B/C/C/A/B/B, and she accomplishes this with the varieties of off-rhyme and slant rhyme that we see here. So, if nothing else, those thirty stanzas are a bravura technical achievement. As we can also see, there are moments when the writing feels a bit as though Orde has given herself a technical challenge and is determined to see it through. That said, even in this stanza ideas and images arise that are striking and heartfelt; for example, ‘Cells that bloom like water flowers.’ This image alerts us to the kind of cell-based metamorphosis that occurs in the transformation of the caterpillar into the pupa, and through the pupa into the butterfly. And the final two lines of the stanza also point us towards the way in which such a transformation is both total but also ‘blind.’ Well, it’s blind to the human observer but for the caterpillar it is part of its evolution.

Later in the poem, the narrator, which feels like Orde herself, becomes part of this transformation narrative:

I have been a stalk, a leaf,

xxxxxxxA grub, a fish with beak of gold.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxI fear the dark

xxxxxxxxxxxxxWith a double knock

And I hate intruders – that’s the truth.

xxxxxxxAnd here’s the truth: I am half dazzled

xxxxxxxBy a fancy, violent and old.

That ‘fancy, violent and old’ is that she will become part of a metamorphosis that will not transform into some beautiful butterfly. Orde will, ‘break but not awake / Nor hurry that congealing drop of breath / to build myself one butterfly on earth.’ Orde’s lines turn around that ‘build myself,’ which is both intransitive and transitive; wanting to build herself as a butterfly, but also to build a butterfly for herself. That play of the intransitive and the transitive carries on through the rest of the poem as it turns back to the butterfly as, perhaps, Orde herself:

The involutions of her early wings

xxxxxxxInvite a finger’s cruelty

xxxxxxxxxxxxxTo know the damp

xxxxxxxxxxxxxPlace where she once dwelt

Or to deface and itself win

xxxxxxxFrom each cold hollow, guiltily,

xxxxxxxSome of the dews and dustings of her beauty.

The narrator’s personal history is brilliantly pinned down in that image of ‘the damp / place where she once dwelt.’ Here, that place invites the type of cruelty that the narrator has inflicted on the eggs of the caterpillar at the start of the poem; a careless brushing aside that has changed the eggs to ‘grease.’ And then there is the defacing, which seems to come from the narrator, and acts on that earlier life to win, guiltily, some remnant of an earlier beauty.

If there is a redemption in any of this, Orde finds it with suitable ambiguity and ambivalence in the final two lines of the poem. The butterfly finally takes off and ‘When she reaches the tree she finds it full / Of her own shapes and becomes indistinguishable.’

As I’ve mentioned above, there is a surreal element to the poems that Orde wrote at the beginning of her writing career. But that surrealism emerges organically from a clear closeness to the real world. In ‘The Kind Sofa,’ the characters Edward and Emmeline ‘swam on a sofa which became / Their closest friend.’ And yet, to Emmeline, ‘To the hanging moon / Of Edward’s face she could not explain / How he set free her convict mind / To visions flashed off a knife blade.’ Inside this, is the idea of ‘the hanging moon’ of the lover’s face. This image seems to capture so much in an instant, that idea of the moon as an aspect of madness, but also the face of the ‘man in the moon,’ as the face of the lover; the moon, so far away and so cold, which set off the imprisoned fantasies of the woman. Orde reaches into this kind of imagery, and the resonances that are set off within the imagery, but it is both her control of the resonances and yet her ability to allow those resonances to develop that seems so good.

There is a lovely, warm, heartfelt brilliance to the poetry in this collection of Julian Orde. As I have noted, Orde starts off as a surrealist but of a kind of surrealism that is always bound to the real and the observed. And that binding runs through these poems to the poems at the end of the collection. And if the poems at the end of the collection are not in a ‘late style,’ then there is a turning more into that sense of the observed and deeply felt. Feelings for others and feeling for herself as Orde comes to terms with ageing, and what has been gained and lost in what was clearly a life well-lived. There is a comment from William Empson on the back cover of this book, ‘Wonder at nature, wonder at all experience is her note.’ And, by and large, Empson is right.

Ian Pople‘s most recent collection, Spillway, New and Selected Poems, is published by Carcanet.

*****

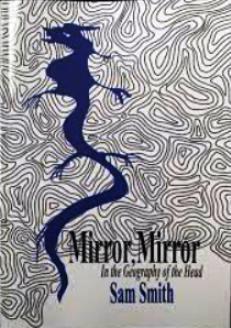

Mirror, Mirror, In the Geography of the Head, by Sam Smith, £12.95. erbacce-press. ISBN: 978-1-912455-30-0. Reviewed by Wendy Klein

What gives a poet the impetus to write a comprehensive volume of poems and prose focusing on mental illness in the context of diagnosis and treatment in and out of hospital settings? What gives a reader, perhaps another poet, the impetus to peruse every single piece, teasing out its significance, indeed, its importance? In 168 pages of poetry Sam Smith offers a detailed ‘geography’ of the world of mental illness through diagnosis, treatment (medical, social, and psychological), scrutinizing practitioners at every level from consultant psychiatrists to ward cleaners. He doesn’t shirk from the gritty, smelly detail of working with individuals whose bodies and minds are ‘out of control’ but are being less than well served by the individuals who are employed to treat them, by a flawed system. Writing from very evident personal experience, Smith explores the relationship between practitioners and sufferers, its negatives and too rare positives, never once losing sight of the commonalities that link the so-called mentally ill and the so-called mentally healthy; that we are all there ‘but for the grace of.’

Smith has chosen to divide this collection into three sections, the first untitled and backgrounding the other two: ‘Problems & Polemics’, followed by ‘Present & Future’. He invites the reader into the world of hospital treatment with an eerie opening poem, ‘Now here’, evoking the atmosphere of mental hospitals, or asylums in Victorian England, buildings also familiar to me from my days as a hospital social worker. Here is a place where ‘pale crickets cheep / among the heating pipes. // ‘Along squeaking asylum corridors / endlessly curving,’. He notes:

The echoes are quick and sibilant,

Without focus.

As if here there wasn’t,

already,

confusion enough.

The use of ‘already’ as a single line creates a note of foreboding of what is present, what is to follow. And follow it does, with a short poem, ‘Palmistry’, where the ‘practitioner/poet’ notes on a pill round, ‘how many (patients) have the same single simian line / cutting across their pink palm / as I.’ He drives the commonality, the mirroring, home in the closing 4 lines:

I know I am not immune, exempt

From these illnesses, that only a feather’s stretch

stops me being the one

passively holding out my hand.

The poems in this first section establish the pattern for the rest of the book with snapshots of interaction between the inhabitants of psychiatric hospitals, including striking portraits of patients and nurses. Slotted in between the poems in each section are 12 ‘case studies’, and a handful of prose pieces that offer further analysis through storytelling, history, and current practice, alluding to the politics of mental health practice in more details in the final section.

To summarise the contents in this way risks missing the poet’s evident compassion for the plight of mentally ill people caught up in processes meant to assist them but leading all too often to a loss of dignity, a sense of belonging. He draws attention to the predicament of hospital staff caught up in inadequacies of the system. Indeed, in the final section of the book he celebrates ‘The Good Nurse’ who: adjusts her body clock / to sychronise with each / rotational shift.’ He lists her many attributes: ‘reading what others have left for her to read, leading the house doctor to the diagnosis as if it was his/her own idea,’ but in the end: ‘The Good nurse, conscience consulted, is looking for another job.

A nursing assistant dreams of being at work with the poet John Clare as her patient: ‘I have got John Clare / by the thin soft part above the elbow / am guiding him back indoors.’ In a superb poem he writes in the voice of Clare himself: I have seen men sat on wards / crouching over their pockets’ contents’, and later: ‘I have sat with men in their massive suicidal silence… The poet/practitioner himself engages in conversation (Smalltalk [1]), where ‘My job once was to sit with men and women who were / intent on suicide… becoming ‘ingenious I my devising of innocent reasons / for anyone to stay alive…’

In the poem ‘Acting Out’: ‘a child of limited intelligence’ is delivered to an asylum at age 6 and…54 years on he’s still /acting out, walking in circles…’ The pattern evolves in a system where children come to realise that carers only care because they are acting mad. ‘Given time’, the poet reflects, ‘they’ll forget they’re acting.’

Without sounding like a textbook of public health history over the last few decades, the poet details the closure of old-style psychiatric hospitals. In ‘As the Asylum Closes’ he writes:

Patients are flesh and blood ghosts of what might have been:

This building a misplaced opportunity, ghost of a chance.

Towards the end of section he allows himself a rant that ‘Humanism is On the Ebb’. The poem is introduced with an epigraph by Gregory Zilboorg (1890-1959), psychoanalyst and historian of psychiatry who wrote that ‘Every time humanism has diminished or degenerated into mere philanthropic sentimentality, psychiatry has entered a new ebb.’ This is a list poem beginning: ‘Humanism is on the ebb. / The asylums are closing, and the police cells are full.’ He continues that: a ‘condition is again a crime’, that treatment’s unavailable, that: ‘The insitutionalised have gone / from walking the asylum corridors / to walking the corridors of streets’. Emphasizing the point is a prose poem ‘It’s a Wage’ slating psychiatry for turning into ‘a garage put among a web / of pitted roads and blind junctions’, setting the scene for the second section, ‘Problems and Polemics’.

This section does what it says on the tin, but without preachiness or pretense. It opens with an arresting sight poem, ‘PrOblEMS and PolEMicS’ sprawled across the page in a zig zag of lines with uppercase and lowercase letters randomly inserted and highlighted. It took me long enough to type those 3 words to discourage me from trying to quote from the poem in the poet’s format so I will not attempt to replicate it here. It introduces a ‘controversial discourse with vicarious effects and norms / symptoms and psychoses / contraindications of medication / alternative remedies / praise and promises / manipulation by punishment and reward / question faculty and function / forget one’s own /human fallibility. If that sounds like an abstract from a textbook, what follows is anything but. The language is clear, the compassion of the poet evident throughout, and the individual pieces rich in detail that might be shocking and surprising to anyone not involved in mental health.

‘Two Men On A Cricket Field’ offers a dialogue between a patient newly medicated and the poet/practitioner where he stresses that: ‘Events things, in a psychotic state, / are supercharged with significance.’ Next, a10-line poem, ‘Where The Sense in This?’ hints at a future of PTSD as 6 men in a warship off the Falklands witness the head of one removed by an Exocet missile: Six Petty Officers survived the explosion / to tell this story over and over again.’ The following poem, ‘Most Often’ muses on the contradictions implicit in the way mental illness / difference is considered dangerous, alongside the way it is exploited and glorified by writers of fiction: Yet, / most often, the mentally ill will seek / unqualified acceptance within the very status quo / that the campaigning writer of fictions / wants changed.’

Smith has gathered most of the case studies into this second section of the book, backgrounding and illustrating how the lives of individuals have played out through getting into treatment, receiving treatment and the effects of both. He tracks how suicides have occurred directly as a result of treatment, and where professional carelessness has played a role in failing to prevent them. ‘If we had believed him when…if we had paid more attention to his complaints about the medication’, etc., the brutal inevitability of the possibly preventable. In the poem ‘We All Swim In The One Sea’, the reinforces a key point. I present the poem in its entirety here:

Psychiatry cannot be isolated

from the society it serves:

mental illness is a disease

primarily of the powerless,

even suicides seen as symptomatic

of sociological states, despair

as a statistic. Because someone

may be in hospital doesn’t mean

that they are ill: often they are

assumed to be unwell solely because

they are in hospital. So do doctors

and nurses become accomplices to

insanity, reliant for a living

upon their own diagnoses.

As he walks us through hospital wards, we see ‘Old People Sit Like Lizards Without Moving’ and:

Any visitor

is picked

clean of news.

In a short prose piece, ‘Frustration upon Frustration’ Smith posts a further warning that psychiatry: ‘On the cusp between medicine and politics is a profession acting like a science,

but with so many variables that it has to – despite its extensive, ever-inventive and all-encompassing terminology – be bogus.’ Strong words! He goes on to suggest that: ‘Politics changes systems, changes societies. Psychiatry, therefore, will only ever be allowed to treat the symptoms, will return its patients time and again, to the social and familiar causes of their illness.’ A depressing conundrum, if ever there was one.

In the end Sam Smith, the poet, though a political poet, lays down no resolution, but puts out a moving and articulate reminder of the dilemmas of a flawed system. He illustrates all his points with incidents, invariably disturbing, with the kind of knowledge only an insider would have and only an insightful writer could express as powerfully. He doesn’t hold back in critiquing mental health practice, while highlighting good practice, but the clarity of the language, and insight, not to mention the power of the poetry itself, sets this book apart. ‘Mirror, Mirror’ is a fascinating and illuminating read which I would not hesitate to recommend, not only to fellow poets, but to professionals working in the field of mental health, service users, and anyone wanting to gain insight into the subject. I can only answer the question I began with, with another question. How could a poet with mental health knowledge/experience not want to take up the challenge of writing a book such as this; how could a reader with similar not want to read it, relish it?

Wendy Klein is a retired psychotherapist who has published four collections of her poetry: Cuba in the Blood (2009) and Anything in Turquoise (2013), Cinnamon Press, Mood Indigo (2016), Oversteps Books, plus ‘Out of the Blue, Selected poems’ from the High Window Press. Her pamphlet, ‘Let Battle Commence’, (Dempsey & Windle), based on letters home from her paternal great grandfather, Lt Robert Tarleton, a Confederate soldier in the US Civil War, is on film https://youtu.be/L2JlbpAdUcU She is endlessly revising a manuscript which might turn into a further collection, possibly her swan song.

*****

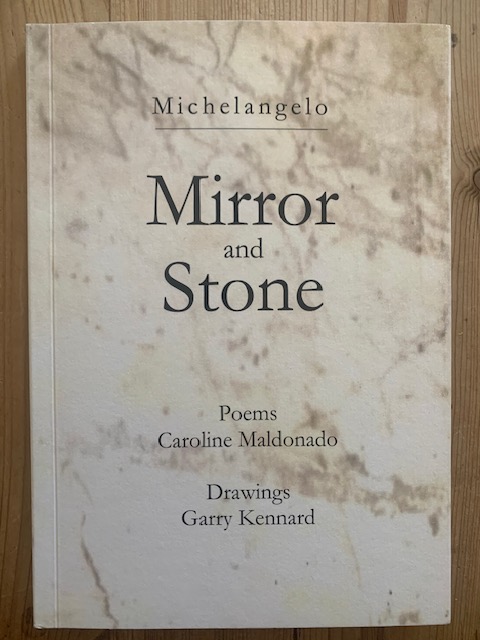

Michelangelo: Mirror and Stone by Caroline Maldonado (Poems) and Garry Kennard (drawings). £10.GV art. ISBN:978-1-7392705-1-3. Reviewed by Kathleen McPhilemy

This beautiful pamphlet is a three-way conversation between Michelangelo, poet and sculptor, Caroline Maldonado, poet, and Garry Kennard who is the artist. Between them they have created an almost three-dimensional portrait of Michelangelo, which reveals, in drawings, poems and translations, deep love and respect for this complex and tormented man. This is reflected in the high production values where the cover mimics the grain of marble and scrupulous notes are provided as a guide to sources. The book is made up of poems inspired by Michelangelo as well as translations of his work and one translation of a sonnet by Vittoria Colonna, who was the recipient of many of the poems written by Michelangelo in the latter part of his life. The original poems are tied in closely to and often quote from Michelangelo as in ‘Stone 1’ and ‘Michelangelo’s seven layers of skin’, while the drawings are all original but breathe the influence of the sculptor, particularly in the way they convey a sense of life and meaning as emergent from stone. Kennard explains that his drawings were selected to ‘go alongside Caroline’s poetry’ but they are ‘decidedly not illustrations of it’ and that although many of the drawings have reference to Michelangelo’s work, he hopes ‘they are more echoes than imitations’.

Michelangelo’s poetry is much less well-known than his art, but he wrote an enormous amount throughout his life, which often reflected his personal conflicts and philosophic struggle. It is only recently that the quality and importance of this work has begun to be recognised. Of necessity, the poems addressed here are only a tiny selection of the whole and Maldonado has chosen several which pertain to his friendship with the Marchesa Vittoria Colonna. She makes only passing references to Tommaso de’ Cavalieri and avoids discussion of the sculptor’s sexuality, partly because she is focusing on his beliefs about art and partly because, I think, she finds Colonna a fascinating character in her own right. Although it is generally thought that Michelangelo was homosexual, there is no evidence that his relationship with Cavalieri was a physical one and his friendship with Colonna was most certainly platonic. In her introduction, Maldonado suggests that Colonna became Michelangelo’s ‘Beatrice, leading him through and evangelical neo-platonic spirituality.’ The reference to Neoplatonism reflects Michelangelo’s credo that human beauty is a type of divine beauty and therefore a pathway to God, a belief which he struggled to reconcile with his conflicted sexuality and attitude to the flesh. Kennard argues that ‘his images are not of real, living people’ but ‘excavated from profound archetypal forms for which Michelangelo dug deep, both himself and into the marble, which seem to be innate in all of us.’

In this collection, the Mirror poems represent the sculptor’s search within himself. ‘Mirror 4’ and the facing drawing show the profound struggle to discover ideal beauty in the mundane and mortal:

a human figure graced with limbs

of such perfection that his being

is a reflection of the god who

is love, beauty

as pure light

‘Michelangelo’s Seven Layers of Skin’ explores the difficulty of achieving this spiritual quest amidst the temptations of sensuality:

Skin-slip water-skin rim of desire I burn I tremble when

touched, scent of my lover’s skin rich with his secretions

or even plastic surgery, ‘lipstick eyeshadow injection knife / I would be made more perfect’.

The italics indicate a quotation from Michelangelo. These feelings of guilt, the desire to escape the flesh while at the same time idealising human beauty, lead to the self-torture, suggests the poem, which made the painter portray himself as St Bartholomew holding his flayed skin.

The Stone poems, like many of the drawings, deal with Michelangelo’s belief that the figure lay within the raw marble and it was the sculptor’s job to free it, a process which is summarised in Stone 2, a translation of one of his own poems. The second poem in the pamphlet, “Other dimensions’ contrasts the sculptural process of subtraction to the writing of poetry, ‘Words, he adds. / One to another.’ Sculpture is seen as a spatial and static art while poetry operates in time and space:

But words can travel through time

travel through space

sending love to La Marchesa in Rome.

In this way a small poem

may grow larger than David

or even St Peter’s Basilica.

It is difficult to overstate how delightful this small book is. Its delicate respect for the Renaissance artist transcends the centuries in bringing us closer to this extraordinarily troubled, extraordinarily gifted man. The drawings, the poems and the translations exhibit a fidelity to him which make this a work to be treasured and which should send us back with a new awareness to the art and writings of Michelangelo himself.

Kathleen McPhilemy grew up in Belfast but now lives in Oxford. She has published four collections of poetry, the most recent being Back Country, Littoral Press, 2022. She also hosts a poetry podcast magazine, Poetry Worth Hearing.

*****