*****

Rory Waterman: Come Here to This Gate • Amy Abdullah Barry: Flirting with Tigers • Jack Little: Slow Leaving

*****

Come Here to This Gate by Rory Waterman. £11.99. Carcanet. ISBN: 978-1-80017-396-5. Reviewed by Stephen Claughton

In this, his fourth collection, Rory Waterman covers some familiar ground and strikes out into new territory. ‘All But Forgotten’, the first of its three sections, is a sequence about his father’s death from alcoholic dementia and cancer; the second, ‘Come Here to This Gate’, contains poems on a variety of subjects loosely connected by the theme of borders or boundaries; and the third, ‘Lincolnshire Folk Tales’, presents his own take on four local legends.

Readers of Waterman’s earlier books will be familiar with the moving story of his parents’ divorce and his difficult relationship with his alcoholic father, the poet Andrew Waterman. He was still a small child when his mother took him from Ulster, where his father taught at the University of Coleraine, to live at her mother’s house in Lincolnshire (‘when you return from Anchor Bar / her side of the bed will be colder even than usual’). What distinguishes the poems here is their raw immediacy. Waterman has said that most were written at the time as a way of coping rather than with the intention of creating a sequence. The focus is on accuracy; indeed, in ‘Coda’ he describes recording telephone calls with his father’s care home:

every ‘conversation’, from when they called

to when they called. The thirty times you laughed

were cropped and saved on file – and the five

when I was ‘son’. But much of what you’d had

was lost in rage – no good for the sound album

As well as having a ‘Prelude’ and ‘Coda”, the sequence is interspersed with three ‘interludes’ about the past, which provide both context and relief. The dementia poems don’t pull any punches about the indignities of illness and are scrupulously honest about the father-son relationship:

… His nappy fills beneath the blanket

as he talks about school, the ‘miracle’ of my birth –

the flowers on the wasteland of his life

bursting in a meadow of his making,

which we both lie in together, finally –

and this is dignity …

(‘The Shortest Day, Intwood Ward’)

‘Lie’ is a pun, of course. The poem ends:

Then he chuckles, tells me something else I recall

differently. ‘Dad?’ ‘Yes?’ ‘I’m proud of you.’

He grins. It fades. Does he know that can’t be true?

In a particularly poignant poem, ‘Reverdie’, an extract from his father’s ‘Rory Journal’ about an access visit made in a Social Services building (‘where had Daddy miraculously reappeared from?’) is juxtaposed with his own visits to his father’s similarly institutional care home (‘excited, though you can never understand / how I am suddenly here’).

There are some arresting images (‘The sheep-tracks of your mind were worn to trenches’ or ‘Your / silences were trains departing’) and an unusual word choice (‘you laughed a tabescent laugh’—it means wasting away), but by and large the poems are written in a plain style, their immediacy underlined by the use of short sentences, the historic present and quickfire dialogue. They are poems which seem to happen rather than be made.

Those in the second section, ‘Come Here to This Gate’, are more distanced. The title comes from a speech about the Berlin Wall that Ronald Reagan made in 1987 at The Brandenburg Gate: ‘General Secretary Gorbachev, … come here to this Gate … Mr Gorbachev, tear down this wall!’ Each of the title poem’s five stanzas is a vignette of a small incident somewhere where borders have or had a special significance—Northern Ireland, East Germany, the Middle East, Mexico and Korea. Unlike actual ‘border incidents’, these seem inconsequential in themselves, presenting ordinary people in extraordinary situations. The stanzas are joined with the same linking phrase: ‘Across // the border, …’ Although they live in different countries, those involved have the common experience of boundaries.

Ordinary people in extraordinary situations might also be a description of Covid. During the pandemic, Waterman, who teaches at Nottingham Trent University, undertook the Poetry and Covid project with Anthony Caleshu at the University of Plymouth. They invited people to submit their own poems, or nominate others, and published new ones online every day. Ultimately, over 1,000 poems by 600 poets from over 125 countries were archived. In addition, 19 UK poets were invited to partner poets from around the world in writing collaborative poems responding to the virus. From the resulting anthology, Waterman includes ‘The Burr’, an adaptation from his own portion of a collaboration with the Zimbabwean poet, Togara Muzanenhamo. In an uncharacteristically loose and long-lined poem, which he attributes to the influence of Muzanenhamo’s style, he describes a socially-distanced visit to his mother and their walk in the country to an overgrown fountain in what were once the grounds of a country house, only to be escorted off the premises, now part of a ‘new farmhouse / we’d hardly noticed: bright brick over privet.’ The poem’s untypicality is its key strength, the length of the line suggesting the longeurs of lockdown, although the poem itself is far from boring, incorporating the kind of detail that people, whose normal lives were interrupted, began to notice. There is a nice touch about the project itself (‘I tell her about you, that we wrote something together’). It may be that ‘she always likes to know what I do’, but its self-reflexiveness suggested to me the way in which our lives shrank during Covid. The more typical ‘Lockdown Man’ deals with this more explicitly.

The other poems in the section are also set very much in the contemporary world: a man texting his mistress during his marriage break-up; social media asking ‘Do You Want to Share These Memories You Posted’, ending: ‘No. Touch the little X again. / Forget that we were ever there’; a pair of arsonists returning to the scene of their crime, not realising that a CCTV camera has caught them in the act; a lengthy exchange of messages with an old flame, divorced with children, who has got in touch on social media; house-hunting near a prison in ‘First-time Buyers’; the uncovering of historic sex abuse; social observation in ‘Doubles at the Tennis Club’, the title of which sounds like Betjeman, but which is if anything Larkinesque:

He’s a dad, and a lawyer or something. He must get paid

six figures. He’s set the wife up with a cake shop,

or so he’s said. Queen shimmers from the windows

of his Audi each time he creeps it up to the clubhouse

Waterman, however, doesn’t share Larkin’s horror of ‘abroad’ and there are poems from his writing residency in the South Korean city of Bucheon.

He is particularly good at capturing whole situations in the short space of a poem, so it’s perhaps unsurprising that in the last section, ‘Lincolnshire Folk Tales’, he should move from creating miniature stories to writing actual narratives. The four ballads present his own version of ancient and modern folk tales. The first, ‘Yallery Brown’, is about a wish granted to a farmhand by the eponymous dwarf (‘He looked like a gremlin in shrinkwrap’) to have his work done by magic (as we know to expect, it doesn’t end well). ‘The Metheringham Lass’ is about the ghost of a pillion passenger, who died when her airman boyfriend’s motorbike crashed during the Second World War and who now waylays unwary motorists. ‘The Lincoln Imp’ is a rollicking ballad about the famous grotesque in Lincoln Cathedral. ‘Nanny Rutt’ is an old hag encountered by an adulteress in the wood where she meets her married lover. Waterman’s interest in folk tales has given rise to another undertaking, The Lincolnshire Folk Tales Project, which ‘explores the origins, legacies, intertextual and social connections and futures of Lincolnshire folk tales’. I hope there will be more ballads as well.

There are other poems in the collection that make deft use of rhyme and Waterman has said that he doesn’t understand the prejudice that some poets have against form, which he sees as a tool in the kit to be used when appropriate. His forms range from traditional ballads to the experimental ‘A Near-Circle of Cadaes on Not Getting Live-In Care’, in which syllables in a line and lines in a stanza are determined by the value of pi. Even when using the ballad form, he exploits it with considerable fluidity:

… Oh God, I loved summer,

but not what it meant I must do:

a farm-hand’s life’s back-aching toil after back-

aching toil, all summer day through,

then again, then again…

(‘Yallery Brown’)

Both his use of form and the world he describes are thoroughly modern and I was impressed by Rory Waterman’s willingness to take risks in the poems about his father’s illness in order to convey immediacy and directness. The folk tales are hugely entertaining and despite its darker side the collection as a whole is thoroughly enjoyable.

Stephen Claughton’s poems have appeared widely in print and online. His pamphlet, The 3-D Clock, about his late mother’s dementia was published by Dempsey & Windle in 2020. Another pamphlet, The War with Hannibal, was published by Poetry Salzburg in 2019. He reviews for The High Window and London Grip and blogs occasionally at www.stephenclaughton.com where links to his poems and reviews can also be found.

*****

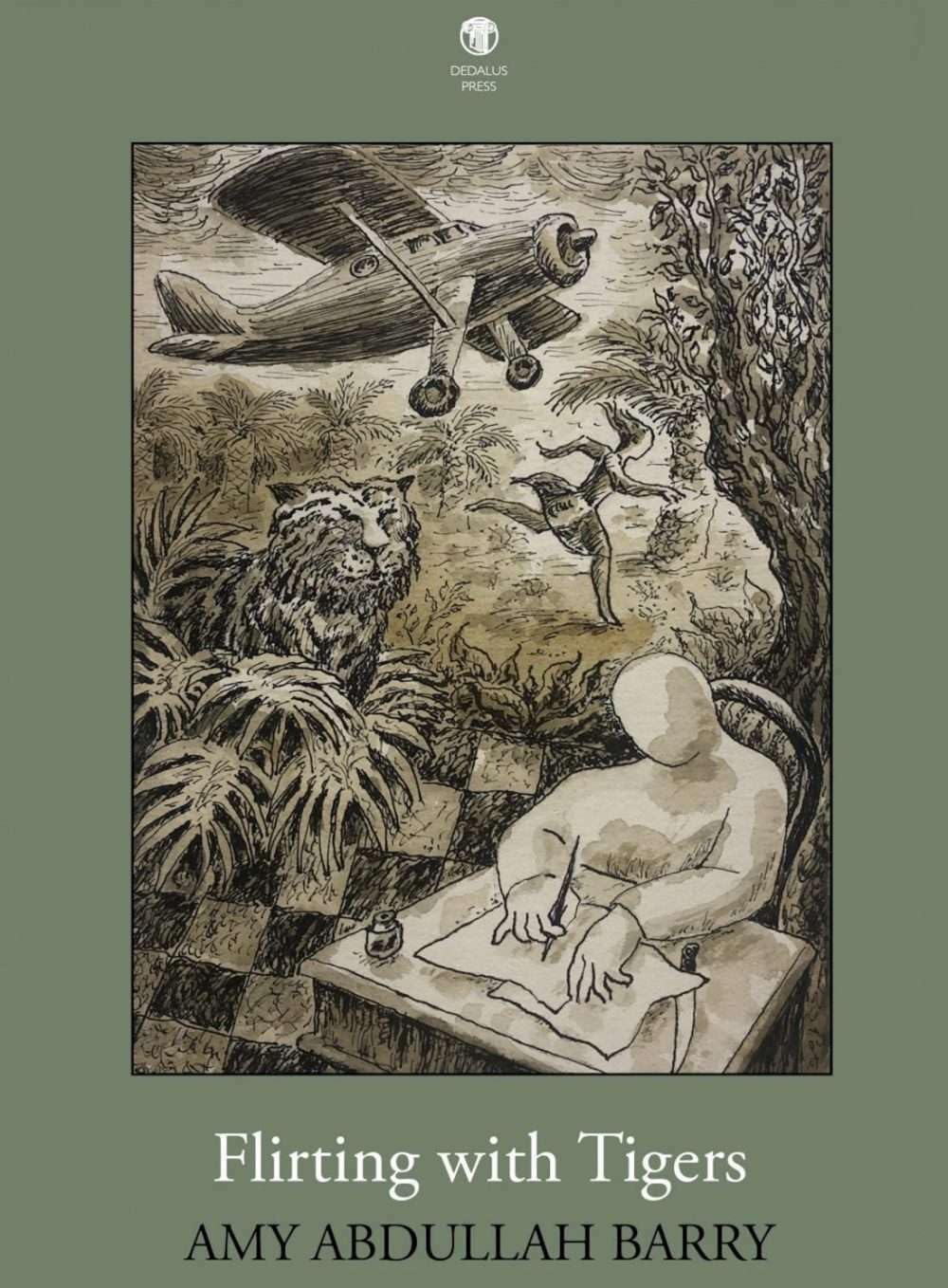

Flirting with Tigers by Amy Abdullah Barry. € 12.50 . Dedalus Press. ISBN: 9781915629098. Reviewed by Patrick Lodge

Whether there is, or is needed, a sub-genre of poetry called ‘travel poetry’ is a moot point. Certainly poetry travels – both Scott and Shackleton took volumes of poetry with them on their Antarctic escapades, indeed, the former encouraged discussion amongst his ill-fated crew as to the relative merits of Tennyson versus Browning. Shackleton was reputed to have a copy of Kipling’s poem ‘If’ on the wall of his hut. Poetry is particularly well placed to encourage time and place slipping and it’s essential compression can lead to some very pointed juxtapositions and truths that allow a poem of travel to make sharp points about being here and there.

Certainly too, poets travel – both involuntarily and voluntarily – and many looked to travel to provide a particular impetus. The Vietnamese- American poet Ocean Vuong has written extensively about his refugee experience – “there’s a discrepancy there, a disconnect, a distance”. Sinead Morrissey saw travel as “a kind of jump start” to her poetry. Elisabeth Bishop saw herself as a kind of sandpiper “just running along the edges of different countries ‘looking for something’”. What Peter Porter referred to as “the dictionary of discontinuity”, is a very useful tool in bringing a striking perspective to work. Thus Bishop’s ‘Questions of Travel’, written soon after her arrival in Brazil, enabled her to understand differently herself and her previous home(s). Indeed, as Lawrence Durrell succinctly put it, “travel can be one of the most rewarding forms of introspection”.

There are, of course, heretics in the church of travel and poetry. John Ashberry’s 1956 poem “The Instruction Manual” marvellously satirises the tendency of travel writing lazily to exoticize

foreign places and fetishize unimportant particularities in the absence of any real insight: ‘We have heard the music, tasted the drinks, and looked at the colored houses’ as he resignedly wrote. The Irish writer, Mick Delap, writing in Magma, would agree, arguing that most writing inspired by travel goes no deeper than the postcards and snaps collected on the way – poetry of travel ‘so often fails to say anything new either about where we’ve been or who we are’. Closer to home, Philip Larkin, in his first collection, admitted the initial attraction of throwing it all up in the air and clearing off but in the end, unsurprisingly, plumped for the ordinary: ‘But I’d go today // Yes, swagger the nut-strewn roads,/ Crouch in the fo’c’sle / Stubbly with goodness, if / It weren’t so artificial’ (‘Poetry of Departures’).

These are the dangers and opportunities that face Amy Abdullah Barry. Born in Malaysia but now based in Ireland and with a background in the oil and gas industry, Barry likes to travel both within Ireland and more widely, the World, and many of the poems in this collection, her first, dip into the pool of travel. The first few lines set up a sense of the exotic – ‘We’ve set up the tent, / pale yellow powdered sulphur round its perimeter / to halt the slithering of snakes’ – and gives a context for Barry’s undoubted ability to turn a neat phrase: ‘I pin / the breath of the rainforest on my skin’(‘The Breath of the Rainforest’) though occasionally the language, especially adjectives, might be made to work harder in pursuit of the poetry.

The collection is the product of a self-confessed ‘culchie on a sunset prowl’ and Barry qua poet maybe sees herself now more ‘curled on a couch / with pomegranate juice, / and chocolate-dipped strawberries, / contemplating another poem’ (‘Music Flows on the Marble Island’) rather than in deepest jungle, notebook in hand. Nevertheless she has the craft to make us share in both her travels and her remembrances of times, and places, past. Indeed, she brings a degree of humour to the work – understanding well the pitfalls of poetry focused on travel. In ‘Don’t’ she notes that ‘Poems have words, but some say nothing’ and generally she heeds this advice, introducing the reader to, inter alia, the Himalayas, Rome, Izmir and the river Suck in County Roscommon. These poems of other places compensate for the occasional pedestrian poem – a care guide for a cat, an imagined return to Robben Island for Mandela work less well.

Clearly though her Malaysian home and family still exert a powerful pull to her emotions and sensibilities: ‘That was another world / Now I’m craving it again, / thousands of miles from home”(‘Ripe’). Often it is Barry’s equivalent of a madeleine that sparks a poem, that allows her to unfold her own myth, as she might put it. Atoosa Sepher, a cookery book author and escapee from Iran, wrote once “as soon as you start cooking, it takes you back. It starts with the smell, then eating it, remembering the gatherings around it”. Barry would undoubtedly agree with this and the poems which work very well here are those focused on memories, particularly of family, summoned up by food. She recalls her “Mama”: ‘chopping, squeezing, mulching, pounding; / turmeric. galangal and dried chillies’ (‘Taste of Penang’). It all sounds pretty idyllic – ‘on the creaking verandah, / we grill our catch / dipping them in peanut sauce, / sea breeze drying our hair’ (‘At Grandma’s’) – but these memories can be bittersweet.

Where these poems work as more than a taste of the exotic is where Barry introduces an element of surprise and high emotion. ‘Champaca’ is a haunting poem that starts with a sensuous memory of Mama ‘baking sweet moistened bread’ but segues into gusts of antiseptic in the ICU and concludes with a melancholic image of papa walking the garden where the bread oven used to be, breathing in the smell of magnolia: ‘the scent mama used to wear on her hair’. Barry is well aware that she is ‘Here, in the Irish countryside’ and cleverly makes the most of the opportunity for revealing contrast, juxtaposing the mundane and the exotic. Buying mangoes at a Tesco leads into a reverie about herself and her brother harvesting mangoes “from the ground / below dropping branches”. The memory is again bittersweet, the poem is suffused with loss and remorse as Barry admits: ‘All I have is an apple tree now / whose fruits are sour / I must smother them in sugar / to taste.’(‘The Mango Tree’).

But, as the American writer, Thomas Wolfe, put it, “You can’t go back home to your family, back home to your childhood…back home to the old forms and systems of things which once seemed everlasting but which are changing all the time–back home to the escapes of Time and Memory.” In this book though Barry does a good job of trying and this debut collection promises more to come.

Patrick Lodge is an Irish/Welsh poet whose work has been published, anthologised and translated in several countries and who has read, by invitation, at poetry festivals in England, Scotland, Ireland, Kosovo and Italy. Patrick has been successful in several international poetry competitions. He reviews for several poetry magazines and has judged international poetry competitions. His collections, An Anniversary of Flight, Shenanigans and Remarkable Occurrences were published by Valley Press. A poem from the final book was put to music and performed at the 2017 Leeds Lieder Festival. His fourth collection, entitled There You Are, will be published by Valley Press in 2025.

*****

Slow Leaving by Jack Little. £10. Red Squirrel Press. ISBN: 978-1913632175. Reviewed by Belinda Cooke

Jack Little’s Slow Leaving gives us a window onto his adopted country of Mexico contrasting it with his UK roots. Throughout, his poetry reflects a carpe diem embracing of life both sordid and holy, as he reflects on his diasporic self – part bohemian, part Peter Pan – that boy who never grew up – playing on a slide as he waits for his wife after work: ‘[I] climbed to the top and took in the view – / the pines, the Virgin of Guadalupe graffiti. // (Momentary King of the World)’ (‘Resisting the Urge to be Sensible’). The resulting poems range from tight economic structures to free-flowing poems, rich in sound and movement. We are introduced to Mexico old and new, along with his life as a husband and father of a child with dual parentage, here in lines that hint at Little’s bigger picture view of our place in the world – ‘Mestizo’ the Spanish term for mixed parentage:

Mestizo,

As our son will be, components

made from nations pieced together

conquered in opposing parts

the subjugation of the ages

different methods ordered by one God

(‘Mestizo’)

The collection’s concluding poems shift to some beautifully nuanced meditations on the self and place hinted at in the above lines, ranging across spirituality, evolution and landscape. All pointing to the evolution of a very individual poetic voice.

His opening poem ‘Outside a Dublin railway station 3.48 am’ reminded me of The Jam’s 1980s ‘That’s Entertainment’: (‘A police car and a screaming siren / Pneumatic drill and ripped-up concrete/ A baby wailing, stray dog howling’,) with its warts-and-all, alliterative musicality and driving momentum:

paunchy hoodlums crawl the streets, spotted among the sad singing drunks

and lasses whisking alleyways quickly home from work.

The vociferous night cools, and a sweet river stench rises

suspended in seagull songs, and shatters – shards yearning for company

in a northern constellation, night reflecting life on glass…

The collection builds in a similar vein as he shifts to the Mexican city setting. Here he points to a claustrophobic dog-eat-dog environment of communal high-rise living: ‘…I hear our neighbours shouting between frying bacon, beans and tortillas. // Outside, our parking space is still occupied / with the neighbour’s car you scratched meticulously with keys the night before’ (‘From the Staircase’), while remnants of an intimate past are flung from on high: ‘letters unsigned hum with speedy kisses / guilty remembrances of broken affection’ (‘Fifth Floor Secrets’).

Two tightly constructed snapshots of Mexico’s entire history and culture show him the newbie getting to grips with the Spanish dialect, as well as whetting one’s appetite to learn more of Mexico’s history as he strolls past, ‘…the execution tree of revolutionaries propped up now by a couple kissing’ (‘In Tlalpan Square’) ,while, in ‘Ancke’, strong use of the senses and various contrasts really place the reader in the setting – beggars ‘cloaked in primary colours against gravel’ ironically contrasting advertising hoardings, while the old world values of Ancke’s submissive silence, are countered by the guttural sounds of her distinctive Mexican Spanish voice, ‘rough and accented / rounded and sliced…’. The dominance of the Catholic church and the past’s numerous battles for independence are also all touched on – here the poem in full, to appreciate his rich and varied description:

Plautdietsch banking billboards rear up

against the mountain desert backdrop of northern Mexico.

Ice-white Mennonite blondes serve pizza–rich cheese,

ranch palaces dominate a land of bare branch apple trees

where Tarahumaras beg at traffic lights, cloaked in

primary colours on gravel

Ancke, was semi-forbidden to talk to men

except to take orders, her Spanish rough and accented

rounded and sliced in ways different to mine,

her words an efficiency, a stubbornness of five colony generations

this island on a highway leaving Cuauhtémoc

and enveloped in faraway lyrics – Europe, America

in the like-me, not from here – home.

Comparison between home and abroad then dominate the collection, noting in ‘Edinburgh’ how ‘the air tastes different // All Change. All familiar. Strange tranquillity’, that last phrase an unusual contrast to the noisy chaos of the environment seen in the earlier poems. He transforms to the wide-eyed innocent before the no longer familiar UK: ‘I had forgotten what frost looked like //…I stood in awe of winter’, ‘…I had left and returned to English breakfasts / long dark night and an earnest, gradual unknowing.’ (‘Before Christmas 2011)

There is a degree of coldness in his childhood reminiscences, which adds to the poetry’s emotional punch as well as leaving the reader with lots of puzzling questions. He mixes in childhood fragments with unanswered questions about what those times were really like. In ‘View from My Father’s Window’, the limited sea view – ‘an inch of astounding ice cold blue’ – hints at elusive lost opportunities whether his own or his father’s: ‘When I return, I might look at my borrowed inch of ocean’. These rather cryptic reactions are beautifully sustained in ‘Growing up’ where subtle diction – allows contradictions to bounce off each other – ‘sacrament’, ‘stripes and Shadows’, ‘the austerity of childhood’ – all jump out at one with contradictions in a childhood that is far from ‘sugar and spice:

This image is a sacrament

of stripes and shadows:

the gap between zebras and lions

how can I catch

xxxxxxa dog’s bark

or the nourishing folding of the sky, moments before nightfall?

I miss the austerity of childhood,

the unruffled truth of songs

when clouds reminded me of exotic animals,

soft wasps searching for sugar.

(‘Growing Up’)

This is then followed by a poem that maybe gives a clue though it’s not clear is this is Little’s experience, but speaking as a teacher, it is spot on in capturing the experience of child carers – maybe this is the answer to the rather puzzling mystery of what his childhood was about:

You won’t believe me, teacher

he said. My talent is

injecting insulin. He wiped his

grandpa’s brow with cold cloths,

cooked for mother arriving past ten.

When bedtime came, and the clock

was chock-full with minutes,

his homework book remained in his bag

as he dreamt of being tucked in at night,

an ‘A’ star in maths, sliding the needle

in the nook between muscle and vein.

(‘Talent’ )

This said, later poems on returning to his origins show a more homely take on the mix of love and duty that draws people back, him now the grownup with a family to share, promising to visit more regularly to, ‘renew that happy untidiness between us’ (‘Guest’).

Finally, we have some a group of ‘sea’ poems that are both beautiful and mystifying. Aspiring poets often underestimate their reader while experienced ones sometimes expect too much. Here I would have liked Little to leave a few more hints here to pick up his drift, but whatever of that I was certainly carried along by the musicality of ‘Beyond the Cliffs of Achill’:

salt tears lash and crevice in starboard cracks

an undecipherable lullaby

a quivering rhythm of profanities.

Stars dance in your deepest black reflection,

green warp-holes between waves spiral deathly transformation

a damp desert-like universe, beyond reach / so close

the seductive sea cliffs arched moon-white in your

sheer drop of ocean

of basking sharks

of ocean

America.

All we can really latch onto is Little having fun with delving into sea as metaphor to see where it takes him. Thus, the poems that follow then take us on mind-bending journeys, that widen his initial comparisons between Mexican and UK culture to a more existential journey of the self, from ‘The Boat Without an Ocean’ and ‘Cleft’ that gives us Moby Dick style meditations on the sea’s uncontrollability, men lost at sea as well our own mortality: ‘lightning obliterates all true sense. Illusions / of power, above the ocean’s sea mouth / forgotten in his ice breath, a heft of dandled magic’ (‘Cleft’). From here, he considers individuals as just ‘crustaceans’ clinging to rocks in ‘Crossing Lines’.

Little’s collection, finally, takes all to full circle to offer us the only thing about which we can be certain – that life itself will continue:

… of cycles, a nebulae

of circles,

the serenity in returning to dust, repetition

reformed as stars or waves eroding rocks,

carrying silt from far-off island coasts

we are finite diamonds and invertebrates

piled so high we cannot see the peak

before the landslide of insect’s feet

we pretend we’re not afraid

of even partly knowing,

xxxxxxxxxxxxmaking sense of this life in the ripples of stones:

are we not more than our ancestors’ deeds?

a product of semi-known quantities,

the refraction of light, in a blind eye

always returning: all familiar?

(‘Perpetuity’)

Belinda Cooke is a poet, translator from Russian and a frequent reviewer.