*****

Latest Reviews

Mary O’Malley: The Shark Nursery • Myra Schneider: Believing in the Planet • Angela Topping: Earwig Country • Margaret R. Sáraco: Even the Dog was Quiet • Alexandra Fossinger: Recount and Prophecy

Reviews published since the summer issue and available in ‘Older Posts’

Noel Connor & Joan Connor : Sharing the Shore, a Donegal Collection • Victoria Melkovska: For the birds • Alasdair Paterson: Words of Mercury • Yvette: In the Garden of Eden after a Heatwave • Ron Scowcroft: Small and Necessary Lives

Kelly Davis: The Lost Art of Ironing • Patrick Osada: The Warfield Poems • Annie Fisher: Missing The Man Next Door

Martin Malone & Bryan Angus: Gardenstown • Colin Carberry: Ghost Homeland • Ezra Miles: The Signalman

Fleur Adcock: Collected Poems • Thomas A Clark: that which appears • Ruth Bidgood: Chosen Poems • Billy Collins: Musical Tables • Peter Sirr: The Swerve • Michael Bartholomew-Biggs: Identified Flying Objects • Martin Jago: Photofit • A.C. Bevan: Poundlandia

*****

The Shark Nursery by Mary O’Malley. £11.99. Carcanet Poetry. ISBN 9781800174146. Reviewed by Patrick Lodge

In a Carcanet Poetry “Meet the Author” piece, Mary O’Malley confessed to being fascinated by physicists. Interesting people whose theories sound either miraculous or bonkers – just like poetry, she added. O’Malley’s poetry is neither miraculous nor bonkers but, like Eisenberg’s Heligoland, encountered in the poem of the same title in this collection, is the occasion for deep insight into the current state of humanity on this planet notably during and beyond the Covid lockdowns. Wallace Stevens, whose ‘necessary angel’ is referenced in ‘Heligoland’, wrote that “one function of the poet at any time is to discover by his own thought and feeling what seems to him to be poetry at that time”. In this exceptional collection, her tenth, O’Malley takes this to heart and her imagination, poetic craft and sheer rootedness, makes transcendent poetry out of the multitudinous detail that characterizes but does not constrain existence over the last few years.

If anything looked like it would constrain existence, it was the recent pandemic and its consequences. Many of the poems here were influenced by that period and its sense of what O’Malley has described as the “double life” pervading the collection – a life which, on the surface was stilled, frozen but which underneath was all movement. Poetry became an important part of that movement– sufficient for Marcello Giovanelli, Reader in Literary Linguistics at Aston University, to identify a specific subgenre of “Covid poetry”. Poetry was, of course, a means of gaining perspective, of seeking understanding and, above all else, of looking to better times. As Carol Ann Duffy put it when launching an international poetry project capturing responses to Covid, “We need the voice of poetry in times of change and world-grief. A poem only seeks to add to the world and now seems the time to give.” As O’Malley, herself, noted, ‘Dystopia is sudden” and the “Whisper from Wuhan” quickly became a thunderous roar(‘The Lucky Ones’) – this collection is in full ‘giving mode. Despite the ‘…decisions cancelled / choices struck out’, the ‘strongmen and their avatars taking over” there is hope while ‘…the snowdrops / are still blooming, even so’ (‘Even So’).

O’Malley’s “giving” is very much of the positive, hope-focused kind though as with most people she confessed to being always “desperate to escape” during lockdown – not least by following a shipping app showing the world’s seas full of movement. She is very much a poet for whom sea is the vital, once saying that if she “slept out of the sound of the sea” she would feel “the tug of something missing”. Swimming, or fantasising about it, was the desired outlet from Covid. In ‘A Morning Swim’ her craft of precision and economy comes to the fore – the normal, everyday activities of a morning swim are juxtaposed with a background of threat and dislocation but thirty lengths temporarily frees the swimmer who emerges: ‘liquid / as a swallow into gravity’s haul and drag’. The swallow, as hope, can always fly south, though ‘This awful year I can’t follow’( ‘Late Swallow”) and O’Malley, like many, is left only with memories of Lisbon or Paris or, in the beautifully worked, sonnet-form poem, “Lockdown Aubade” of the sea to sustain her. O’Malley was born in Connemara and is closely associated with the west of Ireland. Her father was a fisherman and she often accompanied him at work and in this time-slip poem does so again: ‘…between the heavy curves of the hookers / a ghost slips out of the basin, my father’s gleoiteog // with my seven–year–old hand on the tiller, eyes ahead…’. Seeing the sails of the traditional boats being raised again – like race horses “shifting in their stalls” – after a long time is a powerful statement for O’Malley that there is a good future arriving.

In some ways to call these and other poems “lockdown” poems does a disservice to O’Malley; the poems are not mere knee-jerk pandemic pastorals in a particular time of “hideous chaos” but emerge from the deep roots and sympathy O’Malley has with her omphalos at the edge of Ireland. Eavan Boland said of O’Malley’s sense of place that “she has sought out, with careful language and a vivid tone, the emotional colour of the West she knows” and it is this intimate sense of place, and being alive in it, which characterises O’Malley’s work – as she herself said, “the landscape seems to have been the biggest thing in my life”. As a poet she has always been part of the natural world she describes – involved loosely, for example, in an environmental protection team – not a mere observer and interpreter. On a Galway beach, ‘… I can be silent, read / what the wind writes on the sand. // This is my share” (‘On Tra Mhor’). There may be more creatures and, notably, fish, in this collection (the above quote on landscape does continue ‘…next to and inextricable from the sea”) but O’Malley treats all with humility and a recognition of the essential interconnectedness and importance – as the ubiquitous character, Rat, says in an earlier collection ‘…I too am born /I too live and do little harm.” (‘The Rat” in Playing The Octopus, Carcanet 2016). O’Malley seems as used to and comfortable with the creatures she writes about – real and mythical – as she is to people. It’s no wonder that O’Malley drew solace during the Covid years from this world she knows so well: ‘beauty and the new life pushing up out of the mulch / history leaves under our feet is what gets us through’ ( ‘The Lucky Ones’). The title poem, ‘The Shark Nursery’ – offered in honour of the little dogfish often tossed back into the flow but latterly elevated to shark status – could well be an almost triumphant statement of all us little fishes thrown back into the swim following lockdown.

O’Malley has described the “magnificent kind of whoosh” of coming out of lockdown, but it was a changed world – a “binary world”, more digital rather than face to face and more potentially divisive. She is uncertain of the benefits of this; ‘Citizen’ bemoans the small man reeling home across the street who goes to his room to spout venom on line: ‘Invasion, he writes. Do not be fooled. / They are taking over our once proud nation”. There are many opportunities in a digital world for a modern witch-hunt – ‘…Something / the mob chants should be done / the rest is easy. Tweet tweet tweet. / The wildfire spreads. The wind shifts’ (‘Maleficium’). The chilling ‘The Balled of Googletown” offers a dystopian vision of the digitised world and the complacent, consuming families that inhabit it while crazed individuals shout ‘…I’m the Promised One / Beating on a drunken drum / In Googletown’.

These are salutary warnings but the collection, which ranges widely in subject matter, and the poet’s essential philosophy, is more characterised by O’Malley’s consistent optimistic musicality than any poetic doom-scrolling. An Irish speaker, many of the poems reference O’Malley’s love for the language and Irish culture – notably music. ‘The Singer’, dedicated to Josie Sean Jack, a traditional Sean-nós singer, fisherman and local historian, playfully has sharks in the bay staying true to themselves and guarding their language, ‘with old-style glottal stops / and the broad vowelled diphthongs’, from predatory “experts and tourists’. Poems such as ‘Bright Ring of Day’ and ‘The Siege of Ennis’ reference traditional music with the latter a set dance and the former a famous Irish Air. In both, the embrace of Irish culture is linked to the optimism and hope that O’Malley expresses throughout – with life bursting in “terrible and fabulous’ in the former and the latter offering the sound philosophy that characterises this collection, that ‘It is best to dance / while we can and grieve / as each one goes / then step back in as the music weaves, / the pattern set, and dance again.’ Sound philosophy indeed.

O’Malley has talked of something “in the sound sense in Irish poetry” that seems to seep in through the skin. This excellent collection, regardless of subject-matter is steeped in such “sound sense” and flows off the pages through the reader as elegantly as the sea bearing up a Galway Hooker.

Patrick Lodge’s work has been published, anthologised and translated in several countries. He has read at poetry festivals in England, Scotland, Ireland, Kosovo and Italy. Patrick has been successful in several international poetry competitions. He reviews is also a frequent reviewer. His collections, An Anniversary of Flight, Shenanigans and Remarkable Occurrences were published by Valley Press. His fourth collection, entitled There You Are, will be published by Valley Press in 2025.

*****

Believing in the Planet by Myra Schneider. £9.95. Poetryspace. ISBN: 97819094045557. Reviewed by Wendy Klein

Believing in the Planet is the sixteenth book by eminent veteran poet, Myra Schneider, born in 1936, and it is my fourth opportunity to try to do justice to her work. The scope of this poet’s oeuvre is breathtaking, ranging from her very earliest efforts at children’s fiction, in response to her son’s request for stories, to her ‘personal poetry textbooks’ Writing for Self-Discovery and Writing Your Self, in collaboration with her poetry colleague and friend, John Killick.

A collection of seventy-two pages, broken up into four sections, this book is a heartfelt outpouring of Schneider’s compassion for the natural world. Poseidon, a powerful opening, was inspired by the artist Robert Aldous’ painting on silk (cover image), begins with the poet’s command:

Never mind brilliant brains

and the theory of everything, plant yourself

on a seaweeded shore where wave after huge wave breaks

finishing with neat internal rhymes:

We weep to see buildings crumble, telegraph poles

topple and cars drown but still fail to appease the world’s seas.

Schneider’s interest in and knowledge of art is demonstrated in her many ekphrastic poems. In the next poem, Pool she refers to an image from David Hockney, commenting on the way that looking at a pool during a walk has her: ‘stripping off smart phones, stripping off / presidents and fossil fuels, stripping off cars and envy, / love and poetry, stripping off logic, speech…/’ underscoring the boldness of each gesture through repeating the phrase four times.

In the third poem Grass, the poet muses on the risk of losing familiar plant life in the everyday world remembering: ‘how the green / of the unfettered grass, the trees coming into blossom / nurtured me as I struggled back from illness two autumns ago.’ She later evokes an utterly charming image of Hardwicke’s Woolly Bat:

the tousled body smaller than your little finger,

its tiny triangle ears, bead eyes

and the beautiful leaves of its upraised wings

which fold away tidily to allow it to slip

into a green pitcher’s flaunted cup

The section continues with elegies to plant-life at risk in urban settings such as dandelions, her fear of their demise so acute it sometimes disturbs her sleep, to: ‘grope for the lamp / on the shelf, with a trembling hand pick up a glass of water. / Gulping the cool liquid, I picture dandelions and weep.’ (The Glory) She ends the section in England November evoking the eruption of Etna against a sunset… ‘The image stays, / reminds me how small we are in this astonishing world, /how grievous it is that we don’t act to save it.’ Gorgeous, vivid images remind the reader again of the loss of how much there is to lose. (Taormina)

I’m not sure about the reason for a section break here as this second section continues in a similar vein with a mixture of nature-themed ekphrastic poems and more personal material. A delightful meditation on the world seen through a jar of honey is a gentle ‘count your blessings’ poem urging the Simon in the epigraph to take a crumpet and:

kick your fears for yourself, your nearly

birdless garden, the whole world,

under the table and for a few minutes,

sink your teeth into cushion sweetness.(Honey)

In Brussel Sprouts, a surprising topic for adulation, the John K. of the epigraph is urged to:

‘Simmer / these small vegetables for a few minutes, then sit down / to savour the warmth of these small green balls.’ The poem, Turkey Tails, one of my favourites, takes the reader through a journey from the poet’s childhood terror of turkeys to finding solace in turkey tail mushrooms through an illustration in a book, reminding her of discovering that they are not packed with poison but: ‘…they can heal and I am filled with wonder.’ Schneider’s sense of wonder is wonderfully contagious.

Two long poems are make up section 3 of this book. Both are biographical narratives. The first is a detailed biography of the much-celebrated nun, Hildegard of Bingen, famous as the patron saint of ecology, musicians and writers. The piece focuses on her visions, many of which were produced as paintings. It begins intriguingly, inviting the reader in with the lines:

It’s not the cold slithering like an endless worm

through her body that’s making her shiver,

it’s the startling white of the snow that’s everywhere

and the yellow sun battering her head with light.

We guess we are in the presence of something odd, for which young Hildegarde has found a secret word: the thing’. The immediate sense of what may possibly be an illness, perhaps epilepsy, is revealed and developed well throughout, linking to her profound religious beliefs and visions. A true visionary in spirit, the nun sees ways in which the church could do with reform and seeks to implement them. The narrative is lively and informative, with some lovely lyrical touches: ‘High in the sky / the moon is a silver gladness etc. but overall, the poetry seems to get a bit lost in the narrative.

In the second and shorter of the two long poems, Artemesia Gentileschi, Schneider focuses on the artist’s trauma and one of her most famous paintings. Abused as a young girl by a painting tutor hired by her father, she was marginalized as a female painter during that period (late 1500s). Raped by the painting tutor ,no one believes her story, even after the culprit is tried, a subtle reference to more contemporary issues. She will exact revenge for her trauma in her painting of one of the bloodier Bible stories, Judith and Holofernes, where the heroine kills the debauched general who has tried to rape her, thus saving her town from invasion.

The poet recounts the tale in seventeen 5-line stanzas. The opening line: ‘The anger has been building inside her for a long time’ could, in my view, be stronger. It is expressed in a passive voice, which had the effect of distancing this reader from the ardour, the fury of the young woman. The poet has chosen the present perfect (has been), rather than the occasionally contentious, but more immediate present historic. The rest of the piece is told very simply, ending with an account of Artemesia planning the painting: ‘It will show the world / the debauched face of Holofernes…’ continuing: ‘…She’ll depict herself / clad in a stormy blue gown standing by her maid…’ Despite the intense drama of Artemesia and Judith, the description, telling rather than showing, seems to lack the impact it so deserves, ending with Artemisia ‘reported’ as commenting how her work will be regarded in future: ‘…famous as Caravaggio… her paintings of women as artists, goddesses, mothers nursing babies.’ I missed a furious voice, longed to hear her painting in red, flagrant and illicit: Artemesia and Judith rolled into one. It reminded me that a narrative poem must be more than narrative, something I am certain is achievable by this poet.

Section 4, the final section of this very full book, is titled Five Views of Hokusai, published earlier as a pamphlet (Fisherrow, 2018), which contains reproductions of the prints. In each poem the poet steps into one of the prints, starting with A Shower Below the Summit, where she advises: ‘Don’t linger by the cherry blossoms in the valley…’ cautioning that: the mountain will be irresistible. In the second, River, she imagines losing her footing slipping ‘into a bottomless marsh…’ when a glimpse of Mt Fuji gives her: ‘…the strength to pull free’. . The most striking image in this set is of the cranes in Blue Fiji: ‘… / their necks long and sinuous. Two seem / to be engaged in badinage as they preen and feed.’ The sequence is ended suitably with The Great Wave, and the poet’s certainty that: ‘…Fuji who has overseen / humankind for millennia. Fuji will endure.’

This is a big, ambitious, and powerful book with perhaps a fraction too much squeezed into it. The size, scope and subject coming at this stage of a long poetry career might just have the earmarks of a winding down. I remain unsure about the inclusion of the two narrative poems in section 3, how much they added or not to the theme. Nonetheless it is full of accessible poems on an important topic celebrating what we have and what we might lose. It is also being sold as a benefit to two important charities: The Woodland Trust and Dr Mark Sims’ fund for Cancer Research UK: a good read for a good cause and thank you Myra Schneider for continuing to believe in the planet!

Wendy Klein is the author of three full collections, Cuba in the Blood (2009), Anything in Turquoise (2013) from Cinnamon Press, Mood Indigo (2016) from Oversteps books, and a Selected, Out of the Blue from The High Window Press (2019). Her pamphlet Let Battle Commence, from Dempsey & Windle (2020), is a US Civil War memoir based on letters home from her great grandfather, a Confederate soldier in that war. She is working towards a fifth collection.

*****

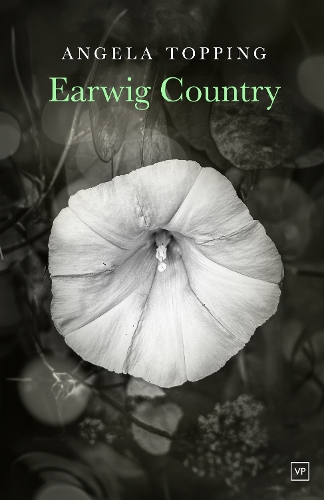

Earwig Country by Angela Topping. £15. Valley Press. ISBN: 978-1-915606-22-8. Reviewed by Kathleen McPhilemy

Although Angela Topping is an established poet with a distinguished track record, this is her first full collection for eight years, which is perhaps why it seems to have a retrospective quality. The book is divided into nine sections, with the first eight seeming to map a roughly chronological autobiography, though the ninth, ‘Women in Life and Literature’, moves away from the personal timeline.

Topping excels in the evocation of the details of ordinary life, so it is perhaps slightly surprising that the first poem which functions as a sort of prologue is a slightly jokey philosophical or theological foray into the origin of language and languages:

I’ll give them words, [God] said, too many.

He chopped up their common language

Into hundreds, each with its own words.

The poet seems on surer ground with memories and her particular skill is to evoke a scene or an object which resonates with the reader’s experience. What household does not have the equivalent of the biscuit barrel that holds ‘the sediment of the living: / missing buttons, coins no longer legal tender, / marbles, nuts, every kind of broken bit / that might one day be needed’? Women my age might remember the thrill of first going for coffee in a department store, in the days when women and girls dressed up to go into town, ‘Coffee in Calverts’. Reminiscences of childhood, teenage years and early adulthood are interwoven with affirmations of the importance of language and literature. At university, she declares, ‘All I’d ever wanted – / the freedom of vast libraries, excited conversations about books, / finding new authors to love.’ Topping is extraordinarily successful in bringing to life the experience of the past, teenage love, first dates and the playing of vinyl 45s on a record player:

The record was tipped from its sleeve

white paper inner removed,

supported by spread fingertips

on the underside of the label, the edge

resting in the crook of the thumb.

‘Love Chronicles’

This is precise and exactly right, but I did wonder whether, despite the resurrection of vinyl, if it would have the same impact on people half my age.

Sections 3 and 4 take on the topical themes of nature and conservation; Section 3, ‘Foraging’ contains the title poem, ‘Earwig Country’ which is an unsettling description of convolvulus flowers and earwigs and probably one of the most successful poems in the collection, in that it is firmly rooted in the real but moves beyond into the world of imagination. Most gardeners will have marvelled at the beauty of the bindweed flower, compared here to the fine porcelain of an expensive tea service, and the pernicious effects of this invasive weed. Here the flowers are ‘full of the plotting of earwigs’, which somehow threaten the innocence of childhood in an apocalyptic augury: ‘Put your ear / too close and you will hear them, whispering / in their marble citadels. They are coming for us still.’

There is a sense of danger here which is unusual; many of the poems are accessible, hopeful, affirmative but perhaps a little safe; ‘Big Umbrella’ asks to be included on a wedding poems list, although ‘With This Ring’ is far more ambiguous. In the first stanza the ring ‘gleams’ and is ‘untarnishable’ and the speaker declares ‘I will wear it till I die’. In the second stanza, she has had the ring cut off, ‘severed from [her] hand / like a broken promise’ but the mark remains – “Just a symbol, no more. / Even the sign of it is enough.’ The reader is left deeply uncertain what this mark is a sign of broken or sustained vows.

The poems which moved me most in this book are the ones which deal with mourning. A degree of rawness creeps in, as in the shocking poem about her mother’s death, ‘A Drink of Water’ and the cynical observation of the disputes over the deceased person’s goods: ‘She wanted me to have this, she claims, /slipping the silver into her bag. // Just a keepsake to remember her by / as a bundle of fivers is pocketed.’ However, it is the three poems for Matt Simpson, her long-time mentor and friend, which convey most strongly the sense of grief and loss. In ‘Another May’, seven years on from his death, she is still imagining visiting the poet in his garden and how they would ‘go indoors to talk poetry, / books and music’. The poem ends: ‘This is my eighteenth elegy for you’, signalling the depth of mourning. The poem I loved, because I recognised the experience, was ‘In Waterstone’s Café, Liverpool’:

I saw my friend, ten years dead,

stuffed into a corner of the bookshop café

…

It took some willpower to stop myself

From going over, saying Hello Matt,

long time, no see. They told me you were dead.

He was fine, slightly plumper, his white hair

as thick as ever. How long after they are gone

do the dead stop giving us false hope.

It may be true, as Eliot argued, that the person who suffers should be separate from the mind which creates, but perhaps it is when the poet is digging down into pain rather than just drawing on memory and nostalgia, that her work becomes most powerful and effective.

Kathleen McPhilemy grew up in Belfast but now lives in Oxford. She has published four collections of poetry, the most recent being Back Country, Littoral Press, 2022. She also hosts a poetry podcast magazine, Poetry Worth Hearing.

*****

Even the Dog was Quiet by Margaret R. Sáraco. US: 15.00. Human Error Publishing. ISBN: 13: 9781948521185. Reviewed by Colin Carberry

In this collection, Margaret Sáraco’s free verse poems are inspired by her working-class immigrant background and her relationships with family, former workmates, strangers and friends, who travel with the author in everyday places but sometimes in extraordinary circumstances. We are drawn into her world with almost documentary-like immediacy. In fact, Even the Dog was Quiet could be described as a memoir in verse, a detailed exploration of the manner in which the poet’s relationships past and present have shaped her and her outlook on the world. Meaning is derived through memory and from apparently minor interpersonal moments epiphanies emerge.

The opening poem, ‘Swoosh!’, seems superfluous and should not have made it past the editorial process, but the subsequent poem authentically records the gritty struggles of an immigrant Italian couple whose documentation and belongings, what little money they had and everything that tied them to their former lives, went up in flames one night:

The night my grandparents’ house caught fire

everything burned

a single cigarette lit cotton curtains

one child saved when thrown from a window

all possessions and money

stuffed in mattresses and hidden

everything lost

(‘Undocumented Roots’)

Other ethnic groups, Irish and Latinos among them, make much of the suffering they endured when oppression, famine, or poverty forced them to relocate to America, and rightly so, but Sáraco reminds us that Italians also suffered ferocious discrimination, as much from fellow immigrants as from homegrown bigots of the Know Nothing nativist strain:

I come from immigrant grandparents, bricklayers and stone makers

who built their own church when no others would welcome them.

Where men left their sweat in stone and priests implied Heaven’s

Gates would open for loved ones if they worked for free,

but no one could test their theory

(‘Bricks, Curtains and the Sunday Comics’)

Beyond memorable autobiographical pieces rooted in ethnicity and generational trauma, an undercurrent of fear, regret, and pathos runs through this collection. Themes explored range from a child who struggles to decode the language of grown-ups to the grief of a dachshund whose Italian-speaking owner (the poet’s grandmother) has died. Poppy, too, is forced to confront loss, and in the process is changed from a ‘funny little dog’ into ‘a broken-hearted old man.’

In ‘Risk’ the poet shudders at the memory of her youthful naivete when on a long road trip she rang up strangers, male friends of friends, with the aim of procuring free lodgings for her and her female companion. Now sixty, the speaker is keenly aware her ill-advised road adventure could have ended tragically. Even her pet dog seemed to sense danger: ‘Two twenty-year-olds driving for twenty-four hours, / calling strangers from the road. Why were we here? / Even the dog was quiet.’

And in a similar type of poem, her older self shudders when she recalls the danger she unwittingly courted as a teenager, drinking and smoking dope among ‘friends and enemies’ alike, even if they all had Italian names:

Friends, enemies, lovers, smoked cigarettes, joints,

passed around dark brown liquor, winced as fire

slinked down our throats. Josephine would steal

homemade wine to share, hidden under her shirt.

Tony got beaten for being out, Angie’s drunken

father came looking for his kid, booming

her name as he barreled down the street.

(‘Them Kids’)

In her biopic, Sáraco described herself as a feminist writer. Although this is not overtly apparent throughout the book, in ‘Dear So and So’ she tackles the theme of sexualized women in ancient myth, accusing the male ‘fear mongers’ who ‘use them / to keep us in our place’ – because ‘Whether half fish / or half human, / they know the anger / we will unleash. / And fear us.’

This collection also contains a number of contemporary travel poems in which the poet explores contexts that, on the surface, appear to be quite different than her own country and milieu (Ireland, Japan, the Yucatan Peninsula) but when she examines the people and settings at eye level Sáraco concludes that people are essentially the same, everywhere.

Some of the poems could have done with a judicious pruning of excess information—one of the inbuilt dangers when working in vers libre—and a number of the poems whose titles are in italics, perhaps five of them, could have been reworked and saved for a future project. But that aside, in the main the poems are well crafted and conceived and enhance our understanding of the author and of humanity. Set on the Gettysburg battlefield, ‘A Collage of Misery’ is, along with ‘Tattered Land’, ‘After Parkland’, ‘Rue’, and ‘A Walk in the Gardens’, among the finest, most fully realized poems in the book.

Colin Carberry is a Toronto-born Irish writer and translator now living in Linares, Mexico. His work has appeared in numerous journals, newspapers and anthologies worldwide (Poetry Ireland Review, Exile: The Literary Quarterly, The Irish Times, Reforma, Jailbreaks: 99 Canadian Sonnets, El Norte, and Život) and in three poetry collections, and his poems have been translated in many languages. His Selected Poems, Ghost Homeland (Scotus Press, Dublin), was translated into Bangla and published in Kolkata, India, in June 2024.

*****

Recount and Prophecy by Alexandra Fossinger. Alien Buddha Press. ISBN: 9798878464413. Reviewed by Rowena Sommerville

In the short author biog at the end of the book, Alexandra Fossinger is described as an exophonic writer – meaning one who writes in a language that is not their native tongue – and it says that she is interested in ‘the spaces between things….. the overlooked, the unsaid’. There is a strong sense of her intellectual and spiritual enquiry throughout this collection, and ‘exophonic’ is not the only word I had to look up – which is not a complaint! I understand that her two main languages are German and Italian (I think she lives in Italy), and in the poem ‘Europe, 2021’ she speaks of her ‘Swedish daughter taking over/ her cousins’ cranky Styrian dialect’ (Styria being an area of Austria) so the context and the frame of reference throughout are clearly pan-European.

In the poem ‘Apfelstrudel’ early in the ‘Recount’ (opening) section of the book, she describes her Oma (grandmother) making apfelstrudel, spreading the dough across the kitchen table:

this paper-thin sheet she filled

with the ingredients

of her harsh love: cut apples, cinnamon, sugar,

pignoli, and a half glass of rhum.

But it seems that Fossinger’s grandmother’s apfelstrudel and her harsh love were both better than Fossinger’s mother’s, for the mother could neither control the dough nor properly love her daughter:

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxThe dough

kept tearing. All those holes

made by her even harsher, not-quite love,

quiet indifference, betrayed her lack of kinship

In ‘The Dead’, she writes of those who have died and are possibly unremembered, saying of one unnamed person:

He sat in his car

Inhaling

exhaust emission

because he knew

we were all lacking air.

And in he same poem she says ‘But the thoughts of the dead/ traverse me/ like a procession of lanterns’ – this is definitely a dark book on the whole, but there is bravery and intelligence in her approach.

The poem ‘Unvisited’, while it is by no means cheerful, is less deathly and it describes a sensation that many aspiring poets must be familiar with – the poem opens with ‘This is the street where poetry comes’ and she lists what varieties of residences might exist in that street, ending with ‘It surely lives in one of these houses/ without me’. Similarly, in ‘The day I went back’ she describes going back from being a poet to being a reader, refusing the ‘May beetles’ in her head, saying:

xxxxxxxxxxNot through me, I tell it,

The way one’s parents’ most memorable words

Are, Quiet. Not now. Say later,

Later.

How late never is.

The final section of the book – Prophecy – looks into the future, both personal and planetary, and seems to find little to celebrate there. The last poem (apart from a one-poem afterthought) is titled ‘Gods of the misty lands’ and references Homer’s Odyssey, and Mary Shelley’s ‘Frankenstein’, through which ‘The Gods (are) forced into the here and now’. She seems to feel that, in becoming creator gods, we have ruined the planet. She says:

The cold lemony light in autumn

will be at its most beautiful again

once mankind is gone –

no one to see it.

Animals on land, in the seas,

are forming an army.

which she sees as ‘The Gods…. reclaiming their place’.

So, Recount and Prophecy is not an ‘easy’ read, but it is interesting, culturally wide-ranging, and often bracing, I hope it finds its own appreciative audience.

Rowena Sommerville is a writer and singer, and lives on top of a cliff looking out to sea in beautiful North Yorkshire. She has worked in the arts for all her life, sometimes successfully. She originally wrote and illustrated books for children, has had numerous adult poems published in magazines, and her first adult collection – ‘Melusine’ – was published by Mudfog in 2021; she had five poems published in a Stickleback leaflet by Hedgehog Press in 2023. She was the Visual Artist in Residence for The High Window in 2022.

Back to the top

*****