*****

Noel Connor & Joan Connor : Sharing the Shore, a Donegal Collection • Victoria Melkovska: For the birds • Alasdair Paterson: Words of Mercury • Yvette: In the Garden of Eden after a Heatwave • Ron Scowcroft: Small and Necessary Lives

*****

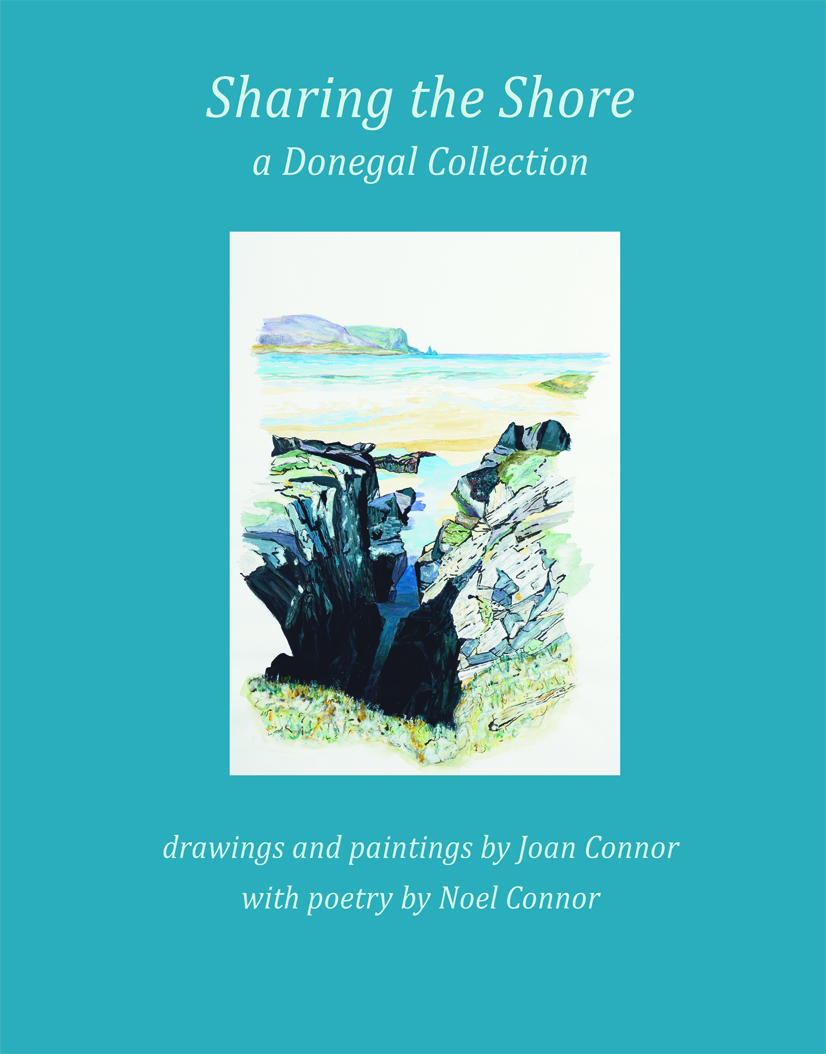

Sharing the Shore, a Donegal Collection: drawings and paintings by Joan Connor with poetry by Noel Connor. £20. Hare’s Corner Press. ISBN 978-1-7385657-0-2. Numbered & signed copies, £35 (plus p&p): profits to Doctors without Borders (MSF). Reviewed by Roger Elkin

What a treasure of a collection this is, replete with outstanding and sensitive art work and exquisite and illuminating poetry. Its genesis is explained on Noel Connor’s website (See http://www.noelconnor.com):

The astounding beauty of the Donegal coastline … has compelled us to return there for over 25 years, fostering a love of this place which we have tried to capture.

These return visits have subsequently evolved into a creative pilgrimage as is clear from this collection, and confirmed in the introductory note:

It offers a shared space, a combined creative response to a place of such personal significance and two individuals’ long and watchful awareness of each other’s work.

And what of the work?

Let’s start with Joan Connor’s drawings and paintings. What is noticeable is that there is no attempt to replicate or represent any particular location via a process resembling artistic photo-realism. Similarly, since the pieces are untitled, there is no identification of specific place, vista or scene. [Because of this, for ease of reader referencing to the paintings and drawings, page numbers are used in this review.] And it must be stressed that the images are in no way illustrations of the poems: the primary artistic concern is capturing the essence and atmosphere of the landscape, including the stark contrasts between the monumentality of the rock formations; the sinuous malleability of the hillscapes on the distant horizons; and the surging power of the sea-swell. An interesting feature is the way in which occasionally the point of view (positioned almost outside the drawing or painting) draws the viewer into the depicted scene with its bay, sand, rocky outcrops, shoreline and the lipping sea. [See page 9 where strategically positioned rocks, blocked primarily in black, invite the viewer to a small sandy cove; page eleven with its skilful visual alignment and vibrant use of colour, including shocks of viridian; and page nineteen with its strategic down-looking view onto the cove, and way out to sea and the distant headland.] Throughout, emphasis falls on the vistas’ foreground and the immediacy of land, the rocky outcrops, the shoreline, the tide’s ingress, and the sea. This is achieved primarily by marginalising skylines to the upper third of the page. Significantly, the pieces are unpeopled, and without bird and animal life. This enriches their dramatic nature: attention falls on the starkly powerful features of the land or sea. The inclusion of living matter would be a distraction.

As to media and technique, Joan Connor possesses a variety of approaches, the product of lengthy and practised observation, commitment, and skilful application. Among them, the following are noticeable in the current collection. There are others.

Firstly, the use of gouache with delicately-painted pastels. [See page 4 where the rhythmic rock striations (presented in amber with touches of lime green) appear to be almost stirring; and page 53 where delicate colours (violet, grey and watery-blue) define the landscape’s particularities; add dimension, texture and relief; and mirror the rock formations in the rise and fall both of the waves and the distant hillsides.]

There are several images where paint is used in an almost casual, but skilled, “abandon” to effectively replicate the subject matter. [See page 27 with its portrayal of the tidal undercurrent and its effect on the beach-sand; also pages 13, 22 & 23 in which Prussian blue, indigo and cobalt blue capture both the louring sky and the rhythms of the sea-swell with its crashing waves, whose tumbling crests are depicted with broad strokes of flashing white.]

There are also several pieces featuring monolithic rock outcrops viewed from close up and presented almost as abstract studies. Here the hatching both replicates and confirms the angles of rock formation. [See page 8 with the fragmented and splintered rock forming an almost man-built wall structure, and explored in monochrome, with amber and ochre highlights. Similar technique is used to depict other rock formations in magnificently splendid detail on pages 36 & 37, and also pages 54 & 55.] These studies are so subtly-nuanced in shading and tone-value that this (re)viewer’s exposure to them extends beyond the merely visual, and verges on wanting to touch, stroke, and feel the rock’s surface texture.

More appropriate in the capturing of particular landscapes is the use of monochrome in which the paper’s white space is harnessed to lend definition to the subject. [See page 17 where the majestic rocky formations (picked out in black) are captured and defined by the blank whiteness; page 21 where the visual illusion of wave-rutted sand and water pools left by the retreating tide is similarly conveyed; and pages 48 & 49 where the blank space dramatically depicts the angled rock formations.]

Turning to review the poetry, and given the contents of this particular book, it might be appropriate to recall a quotation featured in the introductory pages. It is Leonardo da Vinci’s famous saying, Painting is poetry that is seen rather than felt, and poetry is painting that is felt rather than seen. There are oodles of ‘seeing’ and ‘feeling’ moments from both artist and poet in this collection. And what makes the quotation particularly applicable is the fact that Noel Connor is not only an award-winning poet, he is also an accomplished fine artist. In fact, it was his drawings in Gravities (1979);The Book of Juniper (1981); and Wall (1981), which first attracted me to his work. These pamphlets feature poetry selections from Seamus Heaney, Tom Paulin, and Roger Garfitt, respectively. All three are accompanied by Noel Connor’s witty, perceptive and thought-provoking illustrations. However, unlike these pamphlet publications, the poems in Sharing the Shore are entirely free-standing, as are the visual images, features confirmed in an email from Noel Connor:

The paintings and drawings are not illustrations but are independent ambitious pieces that stand successfully alone. I still find it fascinating to give slow consideration to Joan’s work and the pure unstressed pleasure she takes in making it, while I might be yards away struggling with the choice or order of a few cantankerous words in an attempt to make them read and sound as ‘natural’ as her instinctive mark making.

And what of these ‘few cantankerous words’? Given his artistic background, it comes as no surprise that Noel Connor’s poems bristle with visual imagery. Sometimes the expression is delivered in a direct, almost colloquial, manner – is this evidence of his quest to find a ‘natural’ sound? So, jackdaws are ‘bickering … / hopping mad then tattering away / … a gusty rabblement’ (Flight of Fancy); an unidentified wildflower is ‘a scabby little thing’ (Tell me again); and a cuckoo’s call comes from ‘the sleekit bird’ (Hailstones). Occasionally, the imagery, always couched in a physical realisation, startles with its originality and striking perception: such as ‘a midden of hailstones / cupped in sand, overflowing, / spilling down the dune’ (Hailstones); or the unusual expression of sitting by the coast to ‘inhale the view’ (A Thousand Gales); and a sunset wondrously described as ‘an evening curtain drawn / on the hurt coast / closing a long wounded day’ (Add Tears to the Ocean).

Unlike the paintings and drawings, there are poems about the natural world other than landscape and sea. In Ghost Crabs, Noel Connor uses the discovery of ‘a bewildering sight’ of ‘hundreds of dead white crabs / small as thumbnails’ to present a moving catechism that, via the striking ‘thumbnails’ image and the later reference to ‘hieroglyphs‘, draws parallels with human experience:

don’t attempt to decipher

or explain such cruel beauty,

this line of tragic hieroglyphs

left abandoned by the tide.

Similar parallels emerge on the facing page in The Hare, another ‘animal’ poem. While author and companions are ‘Clumsy stumblers / struggling through the undergrowth / … guessing this way and that’, the hare in sharp contrast is on the hill,

looking down on us

… arrogant silhouette

sitting upright on the skyline

lean shouldered, all alert,

the very shape of certainty.

The contrast between the ‘certainty’ in the natural world and the ‘struggling’ of humans is also seen at a personal and creative level in What weight of words. Despite the skilful application of alliterative and assonantal verbal play, visual accuracy, and conceptual wit (compare ‘weight’/‘massive’/‘bulk’ with ‘slim’/‘lightweight’), Noel Connor is aware of the expressive challenges and limitations that his attempts to capture the Donegal landscape present:

What weight of words

could form this rock,

write this massive volume.

Brute bulk sunk deep

beyond some slim description,

beyond my lightweight efforts.

This concern apart, and as can be expected given his background in art, references to colour inform the poems: for example, ‘a drench of inky grey’ (Stealing the Light ); ‘Last light and the rocks / have turned to velvet, / silent and soot black’ (Add Tears to the Ocean); and in Chasing Shadows:

Undercurrents of colour

lift and swell and shatter

in the breaking surf,

cobalt blown to ozone,

viridian frothed and frayed

to wind-crazed white lace.

Additionally, titles of poems such as From Emerald to Indigo and Inventing Blue confirm their artistic influence.

However, probably the most significant artistic reference is the poem dedicated to the art critic, John Berger. Sharing the title of Berger’s seminal work, Seeing is Believing, the allusion in the poem’s opening line – ‘Let me believe’ – is a combination of tentative invitation, command, suggestibility, and request. This ambiguous multiplicity is only partially resolved as the poem explores the possibility of a meeting: ’I recognised your distant silhouette / a figure labouring in thought / pressing forward hunched / in a high collared overcoat’. Could it really have been Berger? Is seeing believing? Or is believing seeing? Rather than answering, the poem’s emphasis shifts to the more immediate, as the poet imagines the two of them,

sharing the wonder

of some washed up detritus

a trail of mangled treasures

drenched in storm surf,

spangled on the mirrored sand.

The focus on the discarded objects, nicely physical but not particularly or individually identified, reinforces the poetic and artistic quest of

learning to look again,

seeing things for the first time,

always for the first time.

Several other poems feature people, including dedications to friends and relatives. In A Thousand Gales, the Connor grandchildren are central to the poetic exploration of an account of the foundering shipwreck of the ‘Santa Anna’ in the aftermath of the 1588 Spanish Armada. The poem’s arresting opening line, ‘History is anchored here’, gives way to a detailed description of the survival of ‘every man … / emerging from the surf in Donegal / half drowned, drenched in all their finery’. What follows is an account of the comparative harmony of similar seekings for shelter by the Connor family in more recent times; and the poem concludes with lines echoing the poem’s opening sentiments:

Here our grandchildren learned to take first steps

toddlers on the warm forgiving sand,

their own small histories anchored to this spot.

But probably the most important ‘people’ poem is the collection’s opening one, I listened to you draw. Though not mentioned as such, the poem is an appreciation of Joan Connor’s commitment to her art and her skilled accomplishment, along with a celebration both of the Donegal coastline and its sharing by artist and poet. The poem’s startling opening, ‘Last night / I listened to you draw’, is sensitively and precisely developed in the second stanza’s appropriately-fine detail of artistic technique:

You pressed the pastel down

in bone dry broadsides,

long breathy drags

exhausted as they scuffed

the parched white paper.

I heard you sketch

with a brasher, harder edge,

tetchy ticks and dashes

to catch a final flash of detail …

Then one last time you leaned away

and left the drawing to itself.

The concept of the work of art – both drawing and poem – having its own life separate from a conscious artistry, but within the artist’s subconscious in contemplation of nature (a feature witnessed in Ted Hughes’s The Thought-Fox and the final bars of Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du printemps) underpins the resolutions of the final verse:

While we slept

single needle pointed blades

bent low and seaward,

swept sideways

gently back and forth

across the moonlit sand.

The breeze transcribed

in each slow fitful sweep,

a show of faultless curves

drawn in our sleep.

There is nothing here (or elsewhere in the collection) that makes Noel Connor’s ‘choice or order of words’ ‘cantankerous’. The poem with its strong visual imagery, internal rhymes, and assonantal and alliterative chimings bears ample witness to the success of his contribution in that ‘watchful awareness’ he shares with Joan, and his celebration of her talent.

This collection is masterly: I urge you to enjoy its skilled evocations of place, and, like Joan and Noel Connor, regularly return to it to savour its beauty in image and word.

Roger Elkin has won over 200 Prizes and Awards internationally, including the Sylvia Plath Award for Poems about Women. His collections include Blood Brothers, (2006); No Laughing Matter (2007); Dog’s Eye View (2009); Fixing Things (2011); Bird in the Hand (2012); Marking Time (2013); Chance Meetings (2014); Sheer Poetry (2020); The Leading Question (2021); Small Fry (2023) and A Party Business (2004). He was editor of Envoi (1991-2006) and has published criticism on Ted Hughes.

*****

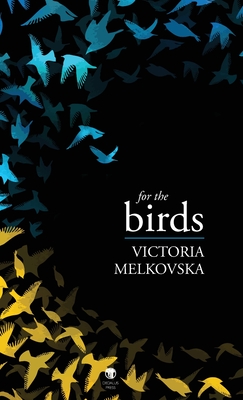

For the birds by Victoria Melkovska €12.50 Dedalus Press ISBN: 9781915629111. Reviewed by J.S. Watts

For the birds is a contemporary, very now poetry collection in terms of its subject matter. Although living in Dublin since 2003, Victoria Melkovska was born in Ukraine and while her eyes now observe her life in current day Sothern Eire, it is clear her heart belongs with her beleaguered homeland. The collection explores her roots in the former Soviet Union to her new life in urban Ireland and concludes with the current crisis in Ukraine following the invasion by Russia.

The collection opens with a poem overtly linking the personal with the political appropriately titled ‘Family Politics’, in which mother and father are identified with Russia and Ukraine: ‘My father’s like Russia: strikes first. / Strikes hard. Strikes where it hurts.’ The book then divides into three sections: ‘We Were From the USSR’, ‘New Land, New Home’ and ‘Warzone’. The first section deals with family history, youthful experiences and memories of Ukraine and Russia. The second section focuses on experiences and observations of domestic life in Ireland and the final section unhesitatingly tackles the horrors of the current conflict in Ukraine.

The poems appear to come from the heart, are often very direct and are at times raw, both in terms of content and style. A good example of this is ‘1955’, the narrative poem that opens ‘We Were From the USSR’. It apparently tells the month by month story of the poet’s family, the death of her great grandmother, the marriage of her grandmother and the birth of her mother. This is the section titled ‘July’:

It is for a month that they are wed:

my future grandmother and my future grandad.

And just as if they weren’t a bride and groom

they go to sleep in two different rooms,

shared with various roommates,

in separate buildings

on the opposite sides of war-wounded Kyiv.

They don’t see each other sometimes for weeks,

so the marital bed neither rattles nor squeaks.

The poems in the section ‘New Land, New Hope’ begin in a similarly direct and simple voice to that of the USSR poems. This is the opening to the first poem, ‘Two Letters’:

Dear Grandad,

hope my letter finds you well

in that white-washed house

with roast pumpkin smell,

where you taught me

to count flies

in the frost-laced window.

As this section of the book progresses, the poems explore views of domestic Ireland, and especially Dublin, whilst still retaining a strong empathy for the home country left behind. The poems themselves become more sophisticated and the poetic voice becomes more in-tune, to my ear at least, to Western English-speaking poetic sensibilities. This is an excerpt from ‘The Back Door’:

Where I come from,

winter drowses on the window ledge,

scratching glass with bristle,

lies in wait for the slightest chance

to stick its foot in the door,

to slither inside,

twirl in for a second

and stay forever.

The poems in this second section of the book are rooted in the day to day detail of the domestic: buying and selling houses, the innocence of childhood uncomplicated by conflict, watching her children grow, a domestic clash over commercial pop versus classical music. Phrases and tone become more overtly colloquially Irish, the classical music station in the poem ‘Funeral FM’ being repeatedly referred to as: ‘Funeral (fecking) FM’. Humour finds its way into a number of the poems. In the case of those dealing with personal trauma, such as cancer, the humour is sometimes black, but it signals an internal strength and personal defiance.

In the third section of the collection the defiance is political and overt and, once again, often raw, as in the concluding stanza of the poem ‘Russians Came’:

Russians, why, by the way you came,

don’t you all just fuck off home?

The poems in this section are primarily war-themed. In contrast to section two, children, when they are mentioned, are mostly orphans or bombing targets. It is in the poem ‘Granny’ that the personal and the political are once again intermingled:

Granny, I’m sorry to say I’m glad

you didn’t live to learn of that,

and of the war, burning down

the cornfields and seas of sunflowers

For the birds is a debut collection of direct poems telling stories of the heart and from the heart of a uniquely contemporary, and, for Melkovska, uniquely personal, conflict.

J.S. Watts is a poet and novelist. Her poetry, short stories and non-fiction appear in diverse publications in Britain and abroad and have been broadcast on BBC and independent radio. Her published books include: Cats and Other Myths, Songs of Steelyard Sue, Years Ago You Coloured Me, The Submerged Sea, Underword (poetry) and A Darker Moon, Witchlight, Old Light and Elderlight (novels). For more information, see her website https://www.jswatts.co.uk/

*****

Words of Mercury. Alasdair Paterson. £10.95. Shearsman Books. ISBN: 978-1848619067. Reviewed by Chrissy Banks

Mercury is a silver liquid metal, the planet closest to the sun and the god of financial gain, commerce, eloquence, messages, communication, travellers, boundaries, luck, trickery, and thieves; he also serves as the guide of souls to the underworld and the messenger of the gods.

Bear this in mind as you read Alasdair Paterson’s fine collection because, in true mercurial style, he ensures you can never know where he’s going to take you next – back to the past, into the future, to the heart of a dream; to his childhood home of Leith or the world of Russian literature (‘Urals’), reflecting by his garden pond or conversing with Anna Akhmatova, Wordsworth and John Donne during a long wait in A & E (‘In sickness and in limbo’). And the direction of a poem is seldom fixed, playing so often on a sudden shifting tone, mood or time period.

What holds this eclectic mix together is the sure voice of the poet, musing to himself or to one of his dead and always to us as he takes us through an emotional and intellectual landscape that is alive with shifts of light and shadow and a particular Scotttish vernacular.

The collection is divided into several sections, starting with childhood memories of family members and Leith. I would stress here that the poet’s deadpan humour and ironic tone ensure that even poems about Grannys avoid any note of mawkishness. It’s not just humour, but wit in its broadest form, delivered with an easy panache, that makes him such an interesting companion. Here is a stanza from ‘Urals: an abcedery’, which occupies a section all on its own. The poem references/ takes a rise out of some great Russian literature, notably War and Peace, using each letter of the alphabet from A through to Z in turn to start each line of 26 four-line stanzas. Here’s the letter X:

X, a tentative kiss on her final note: one more than he deserved

X, as an unknown quantity, flummoxed the Baron completely

X marked the spot, he knew, which was fine once you reached the spot

Xenia, Ksenia, Oksana, Oxania, all at the same picnic:

anyone’s worst nightmare

The poet’s eye falls on the political and social as well as the personal. In a long riff on truth, Paterson takes a slanted look at what we mean by truth in our current world. Who comes to mind for you, I wonder, when he says, ‘This is my truth/ which is not the truth/ but it will be’ and

My truth is currently recruiting

influence wizards to spin

that truth along the cybernet.

Ageing and loss are two themes that run through this collection. Not one but two window-cleaners fall to their deaths in an effectively low-key poem, where neither adults nor children at the poet’s school, where it happens, seem to pay it much attention.

A man fell from the window-ledge

The teacher had his grave news face

All gaunt raw-boned perpendiculars, our primary

It doled out world, pasteurized like milk

We painted our papier-mache castle

(‘Window-cleaners’)

In the section ‘Nature Boy’, mainly short prose poems, both personal and environmental loss hold sway. Paterson seems pulled between the twin tug-of-war teams of loss + age and ‘still got it’ youthful vitality, between communing with/ musing on death ( see especially ‘Shuggy’) and throwing himself into an active life that still holds satisfaction and pleasure. He is bereaved and sometimes haunted, in dreams and memory, by those who have died. ‘Hello again, Mum and Dad’, he says cheerily enough in ‘Hawthorn’. But talking with his counsellor brings the pain of grief sharply into focus in ‘Anemone’.

So I’m out in the garden, looking at my anemones. They were

our special flowers. They’re blooming now. But what I still see

in each centre, no matter how prettily framed by purple or

pink, is a profound blackness. Early days, I guess.

Her eyes, opening for the last time.

Those lines are typical Paterson: not a word too many or few, both poignant and restrained.

And now here he is in ‘Hop’, after enjoying a proud moment when he hops up the steps like the young man he isn’t and later falls to deconstructing the word, spry and its adjutants.

And here I was now, inescapably me,

me onwards for the duration of spry,

like a dancer running out of melody,

a boulevardier running out of boulevard,

a prizewinner running out of shelf;

The seventh decade isn’t always recognised as offering what may be one of the richest times of life, but Alasdair Paterson lays before us in ‘Words of Mercury’ all its mix of memory and emotion, all its close observations of people and places, its complexities of values and thought and, despite the reminders of loss and grief, the gift of a collection of poems that ultimately make me feel, as he says in ‘Daffodils’,

No need to panic. It’s not so bad. It may never happen.

Chrissy Banks lives in Exeter. Her last collection was The Uninvited in 2019 (Indigo Dreams) and she has a pamphlet, Frank, from Smith Doorstop/ the Poetry Business from 2021. Poems in the Rialto, the North, London Grip, IS&T, one hand clapping, Alchemy Spoon, Lighthouse, the Frogmore Papers and Live Canon Anthology 2022 among others.

*****

In the Garden of Eden after a Heatwave by Yvette/ £9.95/ erbacce-press/ ISBN: 978-1-912455-45-4

In the Garden of Eden after a Heatwave is the promising debut collection of Eve Naden, using the pen-name Yvette, in which she explores how it is to be an Eve – a young woman encountering love and desire, but also, inevitably, exploitation and misogyny. Most of the poems are first person, whether that is writing as herself, or as a notional Eve, or as an imagined response from a pre-existing literary character or female archetype.

In the title poem she invokes her mother, to whom the collection is dedicated – the biography indicates that her mother has experienced desertion and mental ill health, but now works to support others:

on the seventh day it rained

it was the kind of rain I could collect in my hands

and pour into my mother’s shoes so she could walk on water

and:

on the seventh day there was a storm

it was the kind of storm I could trap in a bottle

and tip into my mother’s mouth so she could shout louder

In ‘A Gift’ she writes about a father and a grandfather – presumably both hers, though that is not explicit – the poem begins with the gift of an air pistol, and ends with:

I take the air pistol to the garden

and shoot the roses till they bleed

pink red veins

untethered – I wrap them round

each wrist to pour their beauty

into me.

In ‘Visiting Hours at Moorehead Care Home’ she visits her grandmother, who – it is suggested elsewhere in the collection – is developing dementia. She says:

You ask to change seats with tomorrow –

singing, drawn apart.

I hold your hand – you’re boneless.

‘10 Things I Love About You’ does – largely – seem to be a poem about love and desire, with some lovely original phrases. Item No 4 in the list is sunglasses:

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxYou wear them

at parties so no one will talk to you. They cling to the

cliff of your sandy brow. You wear them the morning

after drinking pints of me. I bite the dough of summer

but it doesn’t taste like you do.

Her poems are very visceral, impressionistic, embodied, and she often creates an overall atmosphere of unease and discomfort, especially when she is retelling a tale of harm done (mostly by men), and the poems of desire can be similarly impressionistic and raw, so that sometimes I wasn’t clear quite what type of poem I was reading until the end, and maybe not even then. This powerfully conveyed interplay of bodily sensation/s is a great strength, albeit one I might like to see used with a little more discipline and variety. I did like the way she occasionally uses very specific contemporary ‘cultural’ references to interrupt the flow of imagery – for example, in ‘Tess of The Crewe-ikes’ there’s ‘They say she’s Vicky Pollard’s sister’; and in ‘Ma’s House’ there’s a reference to Kate Bush and her song Babushka.

The booklet has some stylistic/presentational choices that I wasn’t too keen on – the poem titles are not ‘bolded’, so that, especially with the more ‘experimental’ spatial settings, the status of that top line is not always clear (I realise this wouldn’t matter to many readers, but I found it confusing), and some poems are not generally punctuated (which is fine in itself), but then end with a full stop, which I thought was inconsistent, but perhaps I’m over-critical.

In the Garden of Eden after a Heatwave is a debut collection of powerful physicality and emotion, which promises much for the future, and I look forward to reading more from this Eve/Yvette.

Rowena Sommerville is a writer and singer, and lives on top of a cliff looking out to sea in beautiful North Yorkshire. She has worked in the arts for all her life, sometimes successfully. She originally wrote and illustrated books for children, has had numerous adult poems published in magazines, and her first adult collection – ‘Melusine’ – was published by Mudfog in 2021; she had five poems published in a Stickleback leaflet by Hedgehog Press in 2023. She was the Visual Artist in Residence for The High Window in 2022.

*****

Small and Necessary Lives by Ron Scowcroft. Wayleave Press ISBN 978-1-8383378-7-2. Reviewed by Ian Parks

Ron Scowcroft is a very fine poet indeed, and all the virtues that made his previous collections so compelling – a scrupulous use of language, a fine-tuned musicality, and a meticulous attention to detail – are in evidence again here, only in a more concentrated form. Small and Necessary Lives directs our attention to the underestimated and overlooked and finds a language to explore them. In every poem he navigates us through this imaginative hinterland with characteristic grace and poise. In the title poem, for instance, Scowcroft describes the activities of a lover who, on successive days brings ‘a collared dove’, ‘a vole / with hatpin eyes of Whitby jet’, ‘a hawk moth dusted with talcum powder’, and ‘airbursts of splintered glass’ to his loved-one’s door. There is much of the fable and fairy tale in the way that these objects are itemised while their intrinsic significance isn’t explained. Instead, the reader is left to navigate their way through this sequence with intuition and imagination. That the poet provides his audience with little more beyond these exquisite ‘touchstones’ goes some way towards explaining the extraordinary beauty intrinsic in these poems. In the end:

he lays his autumn coat

in agouti shades beyond

the shuttered house,

implicated only in the civet reek

of elder root and scattered remains

of small and necessary lives

outside her door,

We are invited, as readers, to provide the missing information, or simply to read this intimate narrative for what it is – a series of interventions, traces of the outside world making gentle inroads in the house and in the mind.

Not only does Small and Necessary Lives explore the intrusion of ‘the other’ into intimate domestic spaces, it also deals with the presences inherent within the landscape. Flatlands has the speaker lost in a featureless, timeless place where it is impossible to take a bearing or find an easy way out, where ‘every narrow lane / between the fields’ is ‘a right angle to nowhere’. Everything in this world is provisional, shifting, to such an extent that ‘some infusion has infected my dreams’. The speaker tries to make sense of his predicament in the same way that the reader attempts to navigate their way through the language of the poem, tentatively and with caution. So it is that meaning and description become interconnected at a deep and profound level. This approach culminates in After the Wolf which, while being the first poem in the collection casts a long shadow over the other poems and resonates throughout. A wolf is hunted because ‘he liked the taste of children’ and, in the process, rose to mythical proportions in the minds of its hunters. It could, for instance, ‘eat the sun and moon’ and had ‘teeth like a gin trap’. Once caught in a pit, however, it was found dead, ‘shrunk to the size of a stray dog’. Fable, parable, and rumour all have a part to play here, and Scowcroft brings them all together with a deft and masterful touch, saying just enough and always with precision and a concentrated eye. The tone is almost always conversational, but we are never in any doubt that we are in the presence of poetry. All of which makes for an attuned and thematically coherent pamphlet in which no line, no word even is wasted or used without the utmost consideration.

Ian Parks’ Selected Poems 1983-2023 is published by Calder Valley Poetry. His versions of the Modern Greek Poet Constantine Cavafy were a Poetry Book Society Choice. He is the editor of Versions of the North: Contemporary Yorkshire Poetry and runs the Read to Write Poetry Group in Doncaster.

*****