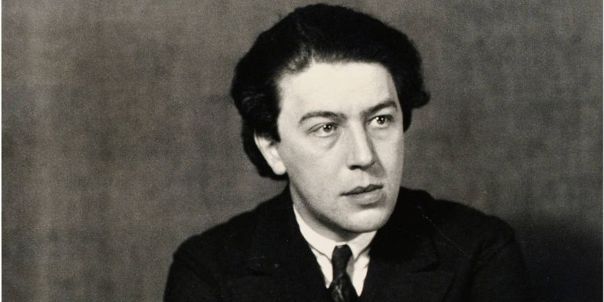

André Breton: Photo of the Poet by Man Ray, 1932

*****

André Breton (French, 1896–1966) was a French writer, poet, original member of the Dada group, and founder of the Surrealist movement. In 1924, inspired by the writings of Sigmund Freud, he wrote the Manifeste du surréalisme, in which he championed free expression and the exploration of the subconscious mind. He was also one of the co-founders of Littérature, an influential journal that featured the first written example of automatism, titled Les Champs magnétiques (The Magnetic Fields). He also helped promote artists such as Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881–1973), Joan Miró (Spanish, 1893–1983), and Max Ernst (German, 1891–1976) by publishing their work in the journal La Révolution Surréaliste (The Surrealist Revolution).

In the 1920s and 1930s, Breton composed two additional Surrealist manifestos, as well as poetry and fiction. His most famous novel, Nadja (1928), is a fantastical love story between the narrator and a mysterious, mentally unstable woman. In the late 1920s, Breton joined the French Communist Party. He left the party in 1935, but remained committed to Marxist philosophy. In 1938, he traveled to Mexico, where he and revolutionary leader Leon Trotsky collaborated on Manifesto for an Independent Revolutionary Art, which examines the relationship between art and social upheaval. Fleeing from World War II, Breton left France in the early 1940s, and lived in the United States for several years, where he organized a groundbreaking exhibition of Surrealist Art at Yale University. After the war, Breton returned to Paris, where he continued to publish more poetry collections and essays on Surrealism.

*****

Dr Arthur Broomfield is a poet, Beckett scholar and essayist from County Laois, Ireland. His current collection is At home in Ireland, new and selected poems (Revival Press). His other works include The Empty Too : language and philosophy in the works of Samuel Beckett. Cambridge Scholars’ Publishing, 2014.His works have been published throughout the English speaking world, and translated into Spanish and Serbian.

*****

Arthur Bloomfield: Towards a new poetics: The re-birth of Surrealism

In a world where wars, environmental disasters and the breakdown of liberal democracies forewarn of an existential crisis, where things do seem to be falling apart, it may be the time to take a cold, hard look at the present condition of poetry. The highest form of literature appears to be fossilised in contemplation on themes of death, beauty, and domesticity. Beauty may be an illusion, birth and death may not be the alpha and the omega; the dishes will be washed. The once credible identity poem has lapsed into a dolly mixture of isms that rages against all the real or imagined hurt inflicted on the author, or on those for whom the author presumes to speak, which can be the pertinent stuff of history and politics; moving, and true, no doubt, but not woven from Yeats’ wool of ‘quarrels with ourselves’ that makes poetry. It is past time, in short, for a revolution in vision, a revolution inspired by the passion that inspired the Romantic and Modernist revolutions. It may be time to consider the thinking of Andre Breton, especially in his seminal work, the Manifesto of Surrealism,1924. The Surrealist movement may have had had an uncertain reception across the decades, but it has had significant proponents in poetry; Paul Elouard, Louis Aragon and, later, Penelope Rousemount (a participant since 1965). Now may be the time, in the light of scientific and philosophical insights, for writers to interrogate Surrealism as a possible means of their poetic intention. Could this be the moment when Breton’s thinking opens new avenues to the understanding of what it is to be, to see if, and how, the power of the imagination can be released through Surrealism, and how that approach can lead to the creation of a new poetics?

The works of Andre Breton intrigue and inspire me, to the point where I’ve been driven to compose a collection of Surreal poetry, The Giant’s Footsteps at the Rock of Dunamaise, dedicated to his memory. ‘The age of swift flow’ is an example of the imagery that comes to me after half an hour or so of automatic writing, or after a session of meditation, from where I would sometimes access the Akashic Record. Usually I would do something practical after a session, chop timber, go for a walk, think of anything but poetry, before sitting down to write. On a good day, the images would flow spontaneously, often faster than the pen could jot them down.

The age of swift flow

Croquet lawns ripple to the whisking of omelettes

and mourn the lost voice and clover clogs

of the landlocked queen of burnt-out daffodil bulbs.

Sea-blown barbiturates and the death dance

of ascending threshing mills

merge with the silly hats on Ladys’ Day

at the ritual hanging. (Broomfield 58)

Poets, not necessarily of the Surrealist persuasion, may have become acquainted with this phenomenon during the creative process. They may call it the Muse, or the Gods. Others could refer to it in the Freudian term, the unconscious.

To privilege the logic of the real world as the source of inspiration, Breton suggests, restricts the use of language; ‘unrestricted language…seems to me to adapt itself to all of life’s circumstances’ (Breton 33) ‘Surrealism …asserts our complete non-conformism…so that there can be no question of translating it at the trial of the real world’ (47). For Breton, the highest virtue of the Surrealist image is its arbitrariness, that it ‘contains an immense amount of seeming contradictions’ (38), in images where unrestricted language opens to unrestricted vision, and ‘by slow degrees the mind becomes convinced of the supreme reality of these images.’ (38) . A couple of examples from Breton’s collection:

The woman with the wallpaper body

The red tench of chimneys

Whose memory is made of a multitude of small drinking troughs

For faraway ships

(Cauvin and Caws 131)

and

The bed hurtles along on its rails of blue honey

freeing into transparency the animals of mediaeval sculpture

(189)

give an insight to an imagination of unlimited boundaries.

Before we discuss Breton’s ‘non-conformism’ let’s look, briefly, at the developments in science and philosophy that, it can be argued, strengthen his thesis for Surrealism. Even a layperson’s grasp of the works on quantum physics of the Danish physicist, Niels Bohr, and on the French philosopher, Jacques Derrida’s insights into presence, will deepen the understanding of Breton’s approach to poetry. In this context the noteworthy are the proven tenets in quantum physics of (1), the mysterious nature of electrons, the sub-atomic particles which, in transit, only exists when they interact with something or someone, and (2) the phenomena known as quantum entanglement. In the simplest terms, quantum entanglement means that aspects of one particle of an entangled pair depend on opposite aspects of the other particle, no matter how far apart they are or what lies between them. To refer back to (1) in an experiment these electrons were fired at a crystal screen; to the amazement of those conducting it, the electron particles created wave – not particle formations, as expected – when they hit the screen. The electrons were changing from being particles to becoming waves. ‘We cannot describe what is travelling as a physical object’ (Al-Khalili), it is a ghostly possibility that only becomes ‘real’ when it interacts, i.e. with the screen and with the observer. From quantum physics we could go on to study the philosopher, Jacques Derrida’s, thinking on presence, and to study Breton’s thinking on the imagination in the light of these, later, developments. When Derrida speaks of presence, he means the actual, imperceivable, present moment, the unknowable void, that is the ghostly presence between past and future, of which we cannot be aware. A possibly, useful analogy to presence may be the moment when we switch the focus of our eyes from one object to another. In that nano second, before the eyes refocus, we are blind to, and unaware of time, space, and existence.

Breton’s vision is of a new poetics, a poetics that delivers that which science and philosophy may be unable to contribute: the power and courage of its poets’ imagination. For Breton, the greatest injustice we could do to ourselves would be to reduce the imagination to a state of slavery. For ‘imagination alone offers me some intimation of what can be.’ (5) Breton’s imagination, through his poetry, was foreshadowing the thinking of Bohr and Derrida. It is in ‘the marvellous…in this passion for eternity that an exalting effect ( is exercised) only upon that part of the mind which aspires to leave the earth’ (15). Here, in this insight we can detect the vision of the surrealist poet and compare it to the ‘unearthly’ nature of the electron in transit of quantum physics, and to Derrida’s ghostly, unconstituted origin of presence, inspired approaches that fuel the intellectual hunger of the physicist and the philosopher. Or, as Breton puts it:

A carriage road

takes you to the edge of the unknown (42).

Scientists, philosophers, and poets have searched for reality in perception, logically, where true reality may be in the pre-perception domains of Bohr and Derrida, which confound logic. ‘Logical methods are applicable only to solving problems of a secondary nature.’ [Breton. 35]. Surrealists tend to see the perceived world as the surreal. For Breton surrealism is a revolution in the approach to writing – and reading – poetry, a revolution that heralds, rather than delivers its objectives. The hope is that the new poetics will help to reveal ‘the pure joy of the man sic who, forewarned that all others before him have failed, refuses to admit defeat, sets off from whatever point he chooses, along any other path save a reasonable one, and arrives wherever he can’ (46). For Breton, the surrealist valorises the poetic imagination, it stimulates and exercises the mind through dreams and the extreme measure of sleep and food deprivation that reveal access to the strangeness of a dimension that excludes thought, reason and moral judgement. In aspiring to leave the earth Breton’s surrealism is sceptical of what is perceived in ‘the waking state (…) it – (the waking state) – really responds to anything but the suggestion which comes to it from the depths of the dark night.’ The intensity of his rejection of the conventional view of reality drives him towards a vision of reality, a surreality, that he knows he cannot find. ‘It is in quest of this surreality that I am going, certain not to find it.’ (37). In the following lines he echoes Derrida’s impossibility of experiencing the present and his anxiety to leave the earth:

It is there

In the place of the suspension from underneath in the

house of the clouds.

‘

[From The enchanted Well]

(Cauvin and Caws. 165)

Here he is echoed by Maurice Blanchot: ‘Poetry decrees and institutes the reign of what is not’ ( Blanchot. 227).

In the Manifesto Breton describes how a period of hunger effected his imagination, in the following phrase.

‘There is a man cut in two by the window.

On writing it ‘beautiful phrases, phrases such as I had never written before’ came to him so rapidly ‘that I lost a whole host of delicate details, because my pen could not keep up with them.’ (Breton. 21).

Surrealist poetry is more about images than words, images that don’t hesitate to bewilder sensation. Images like

‘A man with his head sewn

In the stockings of the setting sun And whose hands are trunkfishes

(Cauvin and Caws.171).

are borne ‘from a juxtaposition of two more or less distant realities. The more the relationship between the two juxtaposed realities is distant and true, the stronger the image will be,’ nor are the two terms of the image ‘deduced one from the other by the mind for the specific purpose of producing the spark ( as in the association of ideas) but are the simultaneous products of the activity I call Surrealist.’ (Breton.36), Breton wrote in 1924. His thinking predicts the concept of quantum entanglement (mentioned earlier), introduced by Einstein and colleagues in 1935.

Breton delights in claiming that ‘all others before him have failed.’ Like the quantum physicists and Derrida, he fears his quest for, what to him is the Surreal, for them the mystery of the electron in transit, and presence, is certain to end in failure. Yet, like them, he continues to challenge the reign of ‘what is not’ and insist that the power of the imagination will defy mediocrity through throwing up defiant images:

For which the…

Marquis de Sade defied the centuries with his great abstract trees

Of tragic acrobats

Clutching the gossamer if desire

(Cauvin & Caws 143)

If things are falling apart and there is to be a new poetics Breton’s thesis on Surrealism is an indispensable complement to the discourse on meaning and quantum physics. Breton claims that ‘the world is only very relatively in tune with thought ‘and like Einstein, he knows that ‘Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.’

Bibliography

Blanchot, Maurice. 2003.The Book to Come, Stanford University Press.

Breton, Andre. 1969.Manifesto of Surrealism, University of Michigan Press.

Broomfield, Arthur. 2019. The Giant’s Footsteps at the Rock of Dunamaise. Revival Press.

Poems of Andre Breton. 2006. Translated and edited by Jean-Pierre Cauvin and Mary Ann Caws. Black Widows Press.

Rovelli, Carlo 2014. Seven Brief lectures on Physics. Allen Lane, Penguin

Derrida, Jacques.1997. Of Grammatology, Johns Hopkins University Press.

Professor Jim Al-Khalili. 2019. The Secrets of Quantum Physics.in BBC documentary.