*****

Martyn Crucefix: Between A Drowning Man • Matthew Stewart : Whatever you do, just don’t • Fiona Larkin: Rope of Sand • Sarah Salway: Learning Springsteen on my language app

*****

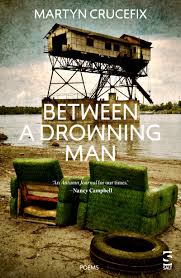

Between A Drowning Man by Martyn Crucefix. £10.99. Salt Publishing . ISBN: 9781784633059. Reviewed by Mat Riches

The introduction to the first section of Between A Drowning Man states that it draws on two texts. The first is Hesiod’s Works and Days, and the second of which is described as

the type of poem known as a vacanna originated in the bhakti religious protest movements in 10-12th century India. using plain language, repetition and refrain they were written to praise the god, Siva, though also expressed a great deal of personal anger, puzzlement, even despair about the human condition […]

This helped put everything into context for what followed. One third of the way in I started to think of it as a man shouting at clouds in book form, of someone railing at things in the world that are beyond our control. And may be it is all of this, but it also much more than this. I think it becomes a lesson in acceptance.

In a post on his own Blog, Crucefix describes these poems as starting to arrive after reading the Vacanna poems in 2016, and how the poems began to accumulate after that while ‘staying in Keswick at the time and I vividly remember scribbling down brief pieces at all times of the day and night’ and of having been influenced by Brexit (the bridges are down indeed). However, he also describes in a follow up post that:

I thought of the poetry I was writing as a quite narrowly focused topical intervention, but in the last 4 or 5 years …the poems have come to seem less dependent on their times and more capable of being read as a series of observations – and passionate pleas – for a more generous, open-minded, less extremist, less egotistical UK culture.

And while the Brexit reading is there, these poems speak more to grounding a modern and disconnected world (despite plenty of references to devices for and modes of communication—we’ll come back to that shortly) in timeless themes like love and desire, parenting, ageing, joy in nature, false idols, and much more, and this is just in the first twenty or so pages.

Picking one of those themes at random, we can see how false idols are covered, but also how deftly he weaves in modern references to something that is both timeless, and of its time, and with that very human . In ‘the six pack on the side’ we are told:

the clock is a sinister and impassive god

xxxxxxxxfor the ancients rumour was a kind of god

…

the god of WiFi when we curse its absence

xxxxxxxxand when did difference become a god

We have always been a narcissistic species that pays attention to gossip (‘rumour was a kind of god’), but while our gods have changed as the centuries have passed, we still curse our gods when they forsake us. Not a bad return for a 19-line poem in my opinion.

In order to achieve the ‘more generous, open-minded, less extremist, less egotistical UK culture’ we can see several pleas for more open lines of communication throughout the poems. Some are located in the specific and familial, as in ‘watch the child’ and its discussion of a child chattering away to herself in a coffee shop with her ‘bright picture book’ juxtaposed with ‘her mother at her cooling latte / at her macchiato / at her cooling skinny medium cappuccino // […] her mother’s ears wired casually // with two scarlet buds.

The child is broadcasting and communicating in a carefree way vs the mother’s more deliberate inward-looking approach, a shutting the world out for some respite. And while this could be a judgmental poem; it’s not. It feels like an invitation to consider both sides, both needs here. The refrain of ‘all the bridges are down’ lands particularly well here, both for the protagonists of the poem, but also for the reader.

However, while some pleas are located in the specific there are some more general ones to be found. In ‘he thought of this time’ one man recounts a litany of disappointments and emotions from his father. The poem draws from Hesiod and his idea of the fifth age where modern man was created by Zeus to be evil, selfish, weary, and burdened with sorrow. It’s a two-footed tackle on humanity from the whistle:

he thought of this time as a fifth age

that he’d be better off dead or not yet born

working all day he would fear the night

had heard of children born prematurely grey

and the fraying bond between fathers

and sons between mothers and daughters

between host and guest between different races

It continues without reprieve about a world where:

[…]the hopeless

are advanced and further advancement

lavished for no more than just chancing it

respect a word more spoken than heard

the educated full of corrosive cleverness

and compassion the greatest of virtues

an ebbing tide you see where it glints

on the horizon

At the time of writing it’s easy to feel like these lines are as contemporary as it’s possible to be, and yet it’s arguable they are evergreen observations about humanity. However, I suspect that’s the point.

We’ve touched upon references to modern-day totems like WiFi, coffee types and headphones already, but this section is filled with them. Further examples include references to Google Maps and ‘five-star online reviews’ in ‘fifteen kilometres of traffic’ and ‘stoke a fire under your silk blouse’ respectively.

This all reaches its zenith in the final poem of the section, ‘this morning round noon’. The poem moves from personal notes about scattering ashes, a son’s birthday (and him being in huge debt at 21, one presumes from being at university) through to:

an American punk band form Nashville

posting abuse about a young Buddhist woman

refusing anaesthetic

The lines are punctuated by phrases like ‘likesharelike’ or ‘likeclicklike’ or ‘smileyfaceicon’. It’s the diaristic nature of the whole section writ large and transmitting thoughts to the page (albeit the printed page, not the Facebook page) as they occur. As an aside, this running together of words, coupled with the entire book’s distinct and clearly deliberate lack of punctuation (save a few dashes here and there) add to the observational nature of the poems, of thoughts being pulled from the ether. However, this is very much not to say that these poems aren’t considered and crafted—they very much are.

The final line of the poem and section is ‘I say the Pantone chart is one of my favourite things’, and while the poem that proceeds this line could be read as a darker version of the Sound of Music classic, less Raindrops on roses and more ‘I was hit by a car likeshare’, but I prefer to take it as a sign that the poem end on acceptance of nuance, variation and being able to communicate the same needs.

As the first section comes to an end there are two poems where the last line of one resurfaces as the start of the next, and it feels like a teaser for what follows in the second section, O. at the Edge of the Gorge.

This was previously published as a pamphlet by Guillemot Press in 2017 and is a crown of sonnets. After the hectic modernity of the first section, there is much to be said for the relative calm of following a traveller, Orpheus, on a journey through Italian countryside observing ‘Glossy fleet black clods of carpenter bees / swirl at the corner of the house / then sink onto spindly lavender stems / alight on blooms stooped // with the weight of insect lives’.

It’s a beautiful opening and a beautiful image that should perhaps be filmed and used as a fine example of what was briefly known as slow TV and shown on BBC4, but in the second poem he describes ‘astronomical time marked by light’ as the sun descends the gorge and church bells tolling, but:

yet come nightfall a different sense

these same sounds sound notes more chilling…

A very real sense of for whom the bell tolls, indeed. As the traveller wends their way round the area, taking notes and sketches of birds, a ‘flock of white doves’, that darkness returns in the form of a buzzard in the eighth sonnet, and gets deeper still in the ninth where he mentions:

like Urbisaglia or some place that has seen

and survived change of use

from sacred temple to church to slaughterhouse

and no gully nor hill can stop it

Urbisaglia is an ancient town in Mid-East Italy that became the site of an internment camp during the second world war, and that knowledge adds further weight to the stanza that begins sonnet ten:

The truth is some survive a while most fail

to conceive the scale of paperwork

to follow change of use from church to temple

next to slaughterhouse.

The cruelty of humanity to itself is mirrored in the “bloody festival / of the bird” in sonnet thirteen as it discusses a raptor above the gorge, and the final sonnet off this crown muses on the fragility of life:

All creatures die sooner blind to the hawk—

left clutching no more than this

as if the hammock he occupies each

and all night too as if strung out

[…]

not falling yet not ever at ease

‘not ever at ease’ could so easily be a final motif for the whole collection. There is a sense that the learnings of this collection are hard won, but there is a connection to the wider world to be had, and that we can find comfort in travelling through it. The final lines of ‘you are not in search of’ in the first section seem apt as a place to leave it:

you might say this aloud—by way of ritual—

there goes one who thought much of life

who found joy in return for a little gratitude.

Mat Riches is ITV’s unofficial poet-in-residence. Recent work has been in Wild Court, The New Statesman, The Friday Poem, Bad Lilies, Frogmore Papers and Finished Creatures. He co-runs Rogue Strands poetry evenings. A pamphlet called Collecting the Data is out via Red Squirrel Press. Twitter @matriches Blog: Wear The Fox Hat

*****

Whatever you do, just don’t by Matthew Stewart. £10.00 Happenstance Press. ISBN 9781910131732. Reviewed by Neil Elder

Is it considered old-fashioned to produce eminently ‘readable’ poems? Pieces that are accessible and that directly communicate with the reader? If so, then Whatever you do, just don’t is out of joint with the times, because the collection is one of the most ‘readable’ and translucent that I have read in a long time.

The poems work well on their own terms, but as a whole a loose narrative weaves through the work so that the poems enhance each other. The collection is divided into four sections, the first of which, Británico, concerns life in Spain, working in the wine trade, feeling oneself not quite at home but not quite an outsider, all of which are essentially autobiographical, though one does not need to know that to quickly gauge the situation.

Adding colour to the backdrop of the collection is Brexit, which brings feelings associated with alienation to the fore. The title of the collection alludes to just how contentious the B word became, as explored in ‘Warning’ where the bilingual and dual national speaker needs care to navigate the UK in 2016. The conflicted state of the nation is captured too in ‘After The Referendum’ where every conversation feels loaded and where the speaker feels uncertain, “I tell myself nothing’s changed, / … Everything’s changed.’

In ‘The Pallets’ we get a glimpse of the turmoil that Brexit has wrought in certain areas, in this case exporting wine. Faced with a change to familiar working patterns, warehousemen are reluctant, and the speaker feels their looks to be accusing, ‘I’m the one to blame now, … británico” and as such he is cast as “a reluctant spokesman / for my country, supposed / to explain our folly.’ The speaker’s quandary, how to defend something he does not believe in, is captured in ‘‘supposed’, but Stewart knows how to break a line, so that that ‘our folly’ is the punchline. The dilemma that hovers in many of these poems is how to assimilate into Spanish life and remain at once English.

The Englishness of the collection is made absolutely clear by the section titled ‘Starting Eleven’ which celebrates footballers who played for Aldershot FC in the 1980s. Twelve poems (the reserve gets included) on lower league footballers of the past is a pretty niche area, and perhaps one needs to have at least a passing interest in the game to really appreciate this section. However, some of the poems can be seen as totemic of figures from our past whose tales of thwarted talent or wasted promise we may recall in other areas of life. ‘Ian McDonald’, for instance, in as Number 10, is ruined by a ‘vicious tackle’ just as success in the form of Liverpool arrives. We also have the agony of hope, familiar to football fans of all teams, with the goal in ‘Colin Smith’ that ‘makes us believe’. The poems themselves in this section are like ‘Paul Shrubb’, ‘Neat, precise and unassuming’, and I can see these sitting nicely in a football related pamphlet, but I found them a curious break in the wider context of the collection.

Other poems in the collection allow the reader a wider perspective on life, and many glimpses of the personal that I found engaging. The business of families, getting older, time slipping by and loss are all here. Frequently poignant are the poems that see Stewart exploring his hometown, returning to the places he frequented when younger. ‘Farnham Library Card’ symbolises the way we may leave a place but that place can stay with us, an enduring presence, don’t we all have things we cannot bring ourselves to discard because of some strange sentiment, in spite of logic? Here the library card rests, ‘After decades in my wallet, / you still survive my monthly cull / of receipts and jotted numbers.’ The comfort of our past and what it may represent jostles next to the busy life of adulthood, ‘receipts and jotted numbers’ and in ‘Crazy Golf’, Stewart skewers the blight of work on time with family: he is unable to ‘simply play’’ and instead –

I wonder who’s lagging behind

On placing their latest order,

Whose invoice is pending – and why

My pointless fretting never stops.

The structure and diction of these lines is a good example of Stewart’s unobtrusive skill. The string of active verbs reflect the restless mind, and the way enjambment is used helps create the sense of rush that finds emphasis with the lengthy sentence finally coming to a halt on ‘stops’. Another strong example of form being married to content comes in ‘La Vendimia’ where workers harvesting grapes “stoop and rise and stoop and rise / grafting … snipping bunches, loading baskets and heaving grapes into trailers.’

Whatever you do, just don’t is well worth spending time with. Whichever side of the Brexit divide you sat on there will be something to enjoy here. The book is beautifully produced, and cleverly captures the fault line that runs through the poems by depicting part of a map of Spain on the outside cover while a map of Surrey is on the inside cover; form well and truly married to content.

*****

Rope of Sand by Fiona Larkin. £10.00 PindropPress. ISBN: 978-1838437398. Reviewed by Neil Elder

A rope of sand is something surely set to vanish, nature and its continuing forces will rub it away, and the poems in this collection examine the transience of things, often via the lens of the natural world. What does endure is something of an individual’s spirit, and the language with which one can claim a part in the world.

Larkin approaches life and all its complexity by exploring the microscopic, a grain of sand, cells within the body, and even breath. These are the basis for poems that take on a scale much greater than these elements. Take the opening poem, ‘Beach’, here Larkin reminds us that a beach, something I immediately see as wide and big in my mind’s eye, is composed of the tiniest particles, “from mica, a runnel of crystal. From shell, from and.” The poem looks closely at the multi-faceted nature of the landscape, “From molluscs, in ankle-deep drifts. / From bladderwrack, itching with sandflies … Shape it from stasis.” The piece finishes with the imperative “Form it as votary, down on your knees.” The pulse of the poem drives towards this final line, there is a tidal rhythm in the alternating use of “Form/From”, so that I am almost compelled to do as bidden, and certainly my thinking on the word ‘beach’ is recalibrated; I am encouraged to see it as the the starting point for all that we have.

In ‘Marine Snow’, we have uncertain lovers, adrift and insecure. Larkin’s metaphor returns to the coast, but this time the dark depths of the sea are used to represent instability. I like the quiet, conversational opening, somewhat at odds with the strange parallels being drawn –

And what do we resemble, we two

But those deep-sea creatures

Excluded from light

The relationship described is “debris”, and the remnants are what the couple exist on, “vampire squid”, once happy in the shallows but now fearful of what lies ahead “where to surface is to die?” This poem is a successful blending of imagery, strangeness and familiarity. I find something appealing in this that is also present in ‘Waking Moon’, a poem that manages to summon Coleridge’s ‘Frost At Midnight’ and find new ways of presenting the scene of a sleeping baby in parent’s arms. The scene is prevented from anything too saccharine by Larkin’s use of an objective speaker in the scene, the parent, who speaks of “fontanelles” and assesses the moment, knowing its worth, but working to understand its mechanics.

In many of the poems there exists a rather detached voice presenting ideas laden with terminology, particularly in those poems that explore the working of the lungs and language, and these I found tricky to engage with. However, there are bursts of more direct outpourings that hit home with verve and joy, such as ‘Recognition’ which celebrates the arrival of the magnolia,

her pink flushed cups, petals tight

on black twigs, her clod courage,

a clench of fuck yous aimed at winter.

The poem appreciates the independence of the flower that will “choose her own sunlit hour” and the short punchy poem works well amidst some of the pieces that demand some work from the reader.

The flash of humour in ‘Recognition’ is welcome, and there is humour in ‘Strumpfluchen’ where it seems a student has designs on her tutor, or perhaps an aspect of her tutor who may not be quite what one would expect. The point I want to make is to draw attention to the inventive ideas and language,

My fruit machine

brain whirred

lemons and cherries,

paid out a jackpot

on marzipan

and to the way Larkin evokes the rush of excitement felt by the student with the tumble of short lines, the momentum of which is undeniable because of where Larkin chooses to break the line and place emphasis –

open in the hands

of the man I wanted

to impress. He lifted

a pair of academic

eyebrows, inviting

my thoughts: but

I tripped at the title.

Throughout the collection, Larkin varies her form and is frequently working to test herself against certain constraints. One group of poems are cadae, a form that works around the numbers in the mathematical formula pi. I can’t claim to have recognised the form, instead Larkin provides notes to some of the poems, a useful tool perhaps, (but supporting notes for poems are things I am unsure of, I often wonder if the poem is really working if it needs a supporting note. But that’s for another occasion).

I need to make a special mention of ‘A Cheerful Letter or Message is on its Way to You’, a beautiful poem of hope where words are “a storm of cheer,”. It is a lovely example of how Larkin can strip away the density of her language and reach something touching in its (deceptive) simplicity.

It took me time to find my way into Rope Of Sand, but having got there, I find I am rewarded by rich language and imagery. I keep returning to the shoreline, more aware than ever of how vital the microscopic is to the whole.

Neil Elder’s The Space Between Us won the Cinnamon Press debut collection prize in 2018. His pamphlet Codes of Conduct (Cinnamon Press) was shortlisted for a Saboteur Award. Other works include And The House Watches On and Being Present. His latest work is Like This was published by 4Word Press.

*****

Learning Springsteen on my language app by Sarah Salway. £9.50. Indigo Dreams Publishing. ISBN 978-1-912876-76-1. Reviewed by Jean Atkin

As I read my way into Sarah Salway’s collection, I found something increasingly engaging about it. Salway’s voice becomes trusted, and close. I think I’ve met Sarah once, many years ago, but I don’t know her except through this collection. As a reader, I began to truly share in her jokes and fears, the way she plants the surreal within the everyday, and especially, through her curiosity, and her pleasure in language.

The collection opens with ‘A Dictionary of How to Live Properly’, truly an issue in the time of Instagram: ‘It’s always out on loan but I know it must exist/ because I can spot everyone who’s read it’. There’s a wry humour here, but the poem then takes off in the unexpected direction of the orchid on the librarian’s desk: ‘I hate that orchid, its white roots/ the legs of a hospital patient trying to escape’.

In ‘Survival’, the world has turned strange when ‘the cloud’ appears: ‘blocking out the sun/ so we had to check our clocks.’ There is adaptation, of a worrying sort: ‘We were kind at first/ but soon it was easier to imagine/ the old couple at number seven/ were on holiday, blinds still down’. Here is societal fracture, and the police are called: ‘when the man/ on the corner filled his house with the homeless’. Echoing the times we live in, the poem narrates the normalisation of cruelty: ‘survival of the fittest graffitied/ on every church wall’. It’s an effective political poem, the surreal unexplained ‘cloud’ standing in for all sorts of challenges – followed by an all-too-recognisable reaction from both ‘citizens’ and the authorities. The title, when you’ve read the poem, has an enigmatic quality.

Some poems circle around life’s often-encountered fears and difficulties. In ‘Folded’, the child’s tongue is: ‘bleached into silence/ after too many/ hot/ words’. And her mother: ‘folds the sound/ back into her like/ taming/ sheets’ – and then the poem shows us, beautifully, the dance of sheet-folding, so often a close link to a parent: ‘moving/ a little closer each time’.

In ‘Why it’s no fun being me at night’, the small hours are a relatable stream of half-awake fears and guilts. ‘Each creak on the wooden staircase/ in our holiday flat/ is a man, always a man,/ with a curved knife as long as himself’. The poem’s protagonist (and I did believe it was quite probably the poet herself, it feels so near) is afraid, but particularly that the man will take: ‘the olive oil the chef/ gave us last night’. Fear is dissolved into everyday ridiculousness: ‘I was writing a poem about death,/ and even now, instead of jumping up/ and rescuing us both,/ I’m worrying over that last line’.

‘Nothing needs to make perfect sense’ says Salway in ‘No Use Crying’, as she goes on living, as we must, after the death of her mother. The poem effectively uses popular proverbs to make links down generations: ‘it’s as if there’s a little goblin inside// leave a bit out for the fairies – / because my body remembers her,/ her mother and all the mothers before’.

Salway has a talent for physical, sensory lines like these.

Several more poems tackle grief. In ‘Perhaps all adult orphans are unarmoured’, Salway deftly uses a dressmaking metaphor to trace her story: ‘although the first cut// is hard, soon every dart of the needle/ weakens the threads to my past’. The passage of time dissolves the impacts of coming across her mother’s handwriting, her father’s glasses. Grief dissipates: ‘It’s time to restitch my self’.

‘In fields of dandelion clocks’, one of my favourites, doubt and worries are examined through a slightly disassociated strangeness:

I wonder what ice cream

made from bluebells would taste like

and why hawthorn turns wool pink’

The poet ‘when it all gets too much’ heads for the woods, where: ‘time moves differently/ in fields of dandelion clocks’. I find this entirely convincing.

‘Learning Springsteen on my language app’, the collection’s title poem, is just hugely enjoyable, poetry as fun. The energy of Springsteen himself comes roaring through in the opening stanza:

I had high hopes after my friend Sian fell in lust

with a tattooed teacher-bot, but she’s a red headed

woman and I’m just so many spare parts.

The poem bounds forward with wit and a sheer pleasure in language: ‘Word by word,/ I’ve been dancing in the dark, proving// it all night but still the app wants more’.

And I really liked ‘words’, a poem about, well, words, that begins: ‘why do some words/ taste of salt and honey?’, and becomes a praise song to the art and practice of reading, and books. The intimacy of the page is evoked, and the poem ends simply and wonderfully: ‘the reader in the book/ the book in the tree/ the tree in the earth.’

This collection was a deserving joint winner of the Geoff Stevens Memorial Poetry Prize in 2022, and I really recommend it. It’s relatable and accessible in the very best way, and delivers a craft and skill in language that has delighted this reader.

Jean Atkin’s third full collection High Nowhere was published by IDP in late 2023. Previous publications include How Time is in Fields (IDP), The Bicycles of Ice and Salt (IDP) and Fan-peckled (Fair Acre Press). Her poetry has won competitions, been commissioned, anthologised, and featured on BBC Radio 4. She has been BBC National Poetry Day Poet for Shropshire and Troubadour of the Hills for Ledbury Poetry Festival. She works as a poet in education and community. www.jeanatkin.com

*****